Saudi Arabia –

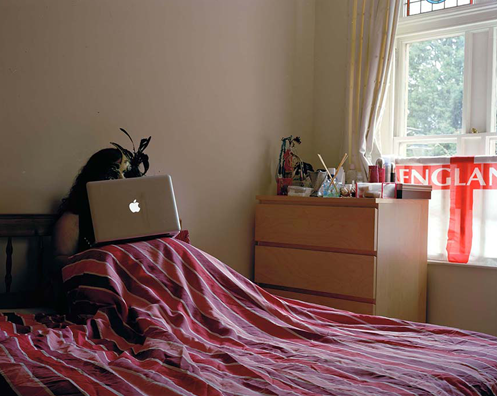

Wasma Mansour shoots intimate scenes and portraits in large format and elucidates the great in the mundane. Moving between Saudi Arabia and UK, her work charts the secret scene, spaces observers hardly get to enter—clothes laid out for the day, distracted or intently distant window glances, women reading, sleeping—turning interiors into public spaces while still managing to preserve her subjects’ anonymity, with the effect that her images are at once specific and magnanimous. Her most recent project, Single Saudi Women, documents the lives and spaces of Saudi Arabian women studying in UK.

Manik Katyal, speaks with Wasma Mansour about her craft, its origin and development.

You originally studied architecture. What made you explore photography?

Well it began by—I worked as a darkroom manager at an all-girl’s college in Jeddha, Saudi Arabia, and so, in a sense I started photography through, you know, basically processing images.

It was a black and white darkroom, and then there was a resident photography tutor who was American—her name is Shannon Castleman—and she got me into photography. I was on a trip to go and get some chemicals for the darkroom, and she lent me her camera. She was like explore, just…

And then that’s what, basically got me into photography, and then I persisted with her a few times. Dealing with photography in that sense made me, take it upon myself and then buy my own equipment. There was this manual 35m camera.

And what year was this?

This was in 2004.

So we’re literally going ten years back?

Yes (laughs)

What was the reason behind this project, Single Saudi Women?

Well, I was always interested in issues relating to women in Saudi Arabia. When I started the PhD I knew I wanted to do something that related to, or concerned, Saudi women.

And because, there is tension when it comes to the relationship between Saudi women and photography—visibility and non-visibility. So then, what basically struck me, with regards to women, is the issue of how the issue of single women isn’t something that is normally talked about.

And it made me aware of their social visibility. When women are discussed it’s always within particular parameters. You know there’s always sort of like a natural association. Basically, women are always associated with their male guardians; so she’s, you know, the wife of so and so or the daughter of so and so.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Does that manifest as a lack of identity?

Not lack of identity, but like this: it’s taken for granted that every woman is—has—a specific life path, and that all women follow that life path. But what about the women who don’t follow that life path? What about the women who do not get married? Or choose not to marry, or get divorced, or get widowed.

What happens to those women? So, and I thought that there was a gap, with this, those women’s representation. So that’s why I wanted to explore this subject.

You began the project while in Saudi Arabia, or only once you got to the UK?

In the beginning of this research, I worked with women in Saudi Arabia, but it was—and this is us going back to how- you have—you do it under the banner of the PhD, or under the banner of academia. It has its merits in that it gives you—it in a sense legitimizes you.

But I mean, because women tend to be really… not suspicious, but—if I just go to women that I don’t know with my camera, they might be really suspicious of my intentions. Especially with the aspect of visibility being, you know, the core of my research.

Academia in a sense provided a safety net that this is something that—there will not be—I will not take advantage of them. This is with their consent, and I’m quite careful with walking them through the process. I get their approval for the images and so on so forth. But the thing is, when you’re dealing with somebody else, and if, let’s say, part of my work basically meant I had to go to the women’s homes, this takes time. Establishing trust takes time.

So I was always cautious, conscious of, meeting deadlines, having to go back, discuss it with my supervisory team, &c., &c. So in a sense, working in Saudi, it did not yield the results that I wanted. It wasn’t really—I don’t know—the images that I took were not satisfactory.

I just felt that, being over there I—bear in mind part of my methodology is that I shoot with a large format camera, so, basically developing the film, I had to wait—like I couldn’t even see the process?

So I had to basically wait until it was time for me to go back to the UK to process the film.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

You couldn’t process the film in Saudi?

No, there weren’t—I mean, the labs had already shut by then and, photography had been almost exclusively digital. I mean the thing is you will have the odd lab here and there, but you cannot really trust them to develop four by five films.

That must have been a really lengthy procedure, going to the UK, getting them processed.

Yes, so that was—for me, that was a little bit stressful, and plus just navigating the public realm in Saudi, like, it’s… On a pragmatic level, it was a bit more… There were so many things, so many steps that I had to take just for me to be able to resolve the issues of getting from A to B, in Saudi. Like I had to get a driver, I had to—do you know what I mean? But in the UK, I could accomplish everything just me by myself. However, the most important thing, or, the most interesting phenomenon that actually encouraged me to start looking at women in the UK, is the fact that there were more single women migrating to the UK because of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program.

The scholarship was established in 2005, and this program basically funds Saudi men and women to pursue their post-graduate degrees, all over various countries all over the world—29 countries I think.

In the UK there were so many that there was like an influx of girls heading to the UK to do their post-graduate studies, and I figured, OK fantastic! This is perfect! For post-graduate degree, so that gives you—even the age group is a very good age group: you know, girls who are from their early twenties until their, up to their late forties, even.

I had a participant who was in her late forties.

So it was great, and another thing for me, what made it even more interesting, was the fact that now these women are locating to a very different environment. I’m curious to see what their surroundings—how their surroundings affect them, and whether, the women will let, will allow these surroundings to like bleed into their private spaces or, have an influence on their identities. So as a subject matter it was a bit more interesting than what I had previously planned.

Were most of these women actually going for post-graduation, or it was also an excuse to move out to explore further?

I don’t really know. I mean, the ones I have met, this was their sole purpose.

And for various reasons—ones—basically it was just for the love of education. Some of them actually did want to, they believed that acquiring a degree from abroad increased their prospects of getting jobs back home.

Some of them just wanted a very different experience, obviously learn how to be independent, you know, so they— I think all women come from— they have various needs and desires behind, you know, from relocating to the UK for the purposes of education.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Do most of your participants want to get back to Saudi at some point?

I had two participants: one girl with a dual citizenship, so she resettled in the UK obviously because of, like, legally she can live there; another girl is working in the UK so yes— and no the rest they’ve all gone back, because here you have another element, which is sort of, the legality of their stay in the UK. I mean, they don’t have the option to say, stay in the UK if they choose to be, do you know what I mean?

Yes, i do. Given the controversial nature of your project, how did you go about finding participants? How did you gain their trust?

Well, I got, I mean I have done very— I’ve tried to seek out the participants in sort of various ways. I did, sending an email, you know.

For participation, I was active online, through Facebook, but I didn’t really, I mean, those approaches didn’t really yield me a lot of responses. I did get some participants, but not as many as those I got to know through personal introductions. I think having someone vouch for your credibility, and that you’re a trustworthy person is really important

Especially in a project as critical as mine.

And on what bases were you selecting the women?

Basically, I looked for girls who are enrolled under the foreign scholarship program

And who were living in the UK. I was quite broad, and of course, single, living without, those who do not live with their male guardians in the UK.

For me this is a very important and determining factor.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Did the fact that you also came to the UK from Saudi have a positive impact on your project? As in, did enable to relate to the women you worked with?

I moved to the UK. Yes, for me, exactly, I was very much exactly like the girls, I had moved to the UK for the purposes of education and I’m a single girl.

So in a sense, this aspect of my identity was, a lot of the girls actually related to that. They found it comforting that, whenever they relayed some of their stories, or their experience about being single, or some of their frustrations, like, they would look at me in a way that yes, you know, what we’re talking about, do you know what I mean?

So this is actually, I have noticed that this is really important, and it helped a lot that they perceived me as someone they, that I could relate to them.

Like, especially that, coming there with a camera, the camera itself can possibly be a very intimidating, equipment, and so, me being the photographer, there is naturally an imbalance of the power relationship.

So I’ve tried my best—there’s no way to demolish, the difference of power, obviously, but I tried to minimise it as much as possible, and I have noticed that this aspect of my identity, being also Saudi and single, and a student, is made more and more relatable to them.

You think, things could have been different if you had a partner?

I think so; I think if I had been married, I think it would.

Married or having a partner?

Married, married. I think if I had been married, it would be a bit, I’m not so sure, I mean I’m speculating here, I think it could. I mean I don’t know. I mean I would worry that perhaps it would make them feel exposed.

Because I am not in the same position of vulnerability as they are, but this is, this is what I would imagine, but I mean who knows maybe things would be different.

Being in the position of a married, being a married woman, in a sense, puts you in an elevated—gives you a particular status in Saudi society that single women don’t have.

You know, a view of them being married, they kind of like, ticked a box.

So in a sense it could be this identity might be something intimidating to some women, but I don’t know, that should be interesting to explore.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Considering you were shooting on a large format, how has the equipment figured in the production of your photographs?

Yes, the thing is, for me the equipment has played a very, very important role. Particularly when shooting the participants project, like I said, for me the—shooting with a large format camera, number one it slows the process down and it engages the participant. For me shooting, or creating the portrait of the participant, had an element of collaboration.

So in a sense, I worked with the participant to build their portrait. I proofed all my images with Polaroids, so in a sense, we take one image with a Polaroid, the participant looks at it, we have a little discussion as to—sometimes an anecdote comes out of it, she told me an experience of something…

That relates to being single, or as her visibility, or whatever, and then if she’s not pleased with that, we take another Polaroid, or if she’s ok with it then we, take it with the film.

So, I realized that scaling up, and by scaling up by using, this, big, obvious, or as some participants call it ‘serious camera’, it validated me as a photographer, to the participant, so they actually started taking me seriously, and they took the project seriously, and they became even more interested in the project.

And it also gave you time and space, to enter their comfort zones.

Of course, and, rendering with a large format camera is, is, I mean, is incomparable to anything else. So for me it was really important to shoot with a large format camera, to photograph the participants with a large format camera.

As for, everything else, I mean I just used a medium format, like a Hasselblad, because there was, you wanted obviously, to get as much of the details as possible from their personal spaces. So you had to use, just to ensure the equipment is, will do the right job.

Giving sitters the freedom to position themselves, within their own space—enhances the idea that these women have more control over their lives in the UK, or was it like vice versa ?

For me this was one of things that I was actually looking into—does relocating to another country, mean that they have absolute control over their life—and, what, from my work I’ve come to the conclusion that, it is much more complicated than that. There is no, I cannot say that moving to London, or moving to Brighton, or Bristol, means that the girl can do whatever it is that she wants with her life, because there are other factors that are at play.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Like what?

There are, particularly that these girls under the foreign scholarship program, that in a sense resembles a controlling entity for their existence here in the UK, so they, the girls, are mindful of the fact they they’ve obtained the scholarship, that means they have to have a particular, they have to give something back.

And they have to excel in their studies, so it, there, if there isn’t social control, then there’s another form of control.

Which is like a lot of peer pressure.

Yeah, there’s a lot of pressure there, and plus there is, one needs to not forget, there is also, the fact that they’re conscious of their Islamic identity as well, and you have some girls who, are mindful, or they actually want to maintain their Islamic identity, so there is, I would say, a negotiation more than a complete departure. In a sense the UK offered them a space to not, in a sense, sever their Saudi identity or leave everything they’ve, had in Saudi, but in a sense just have room to basically shape their identity in a slightly different way.

How do you think it was different for these girls to adjust with their own Islamic identity in the UK?

Well, all the girls that I’ve met—let’s say, for example—so there’s a big difference: the girls that I met in the UK don’t wear the veil, the black cloak, and they don’t cover their hair. So this is a big visible difference between their existence in Saudi Arabia and those in the UK, and that in the UK is that, they do not observe veiling practices in the UK.

But don’t you think here we’re talking cultural identity rather than Islamic identity?

Well, because the thing is, with the veil in Saudi it takes a very interesting position, because it is both cultural and religious. So in a sense, but then again being the fact that it’s much more cultural, the girls don’t feel the need to observe it in, when they travel. However, they keep these veils, which I found very interesting because, that in a sense, suggests, that they want to maintain their relationship with Saudi Arabia, they do want to go back, they do visit their families, and a lot of them actually really cherish their veils.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

So basically, they did not have many difficulties in following their cultural identity?

I wouldn’t say that they would completely follow—for example, like, they’re quite conscious of how they dress in public, particularly—I mean you have to understand like the UK, you do have Saudi clusters in the UK, which in a sense exerts, considerable pressure on some of the girls because they realize that, the Saudi community is in the UK as well, so we can’t, go out dressed up in mini skirts and like revealing clothes because, these people might talk about us and, and you have to understand the aspect of the identity, particularly concerning the girls is always tied to her family name. So she’s not only preserving her reputation, she’s also preserving her family’s reputation as well. So that in a sense is a huge pressure and a very important aspect that determines how the girls choose to behave.

Seems like there’s a considerable amount of pressure on them to excel as well as to take care of their customs and identity with respect to the community based in UK, which might affect their family names.

Yes.

So in a sense their family name is a very important determining factor for how the girls basically reveal themselves. Not only in public, how they choose to reveal themselves to me through photography.

Interesting!

Yeah, which is one of the reasons why the girls are basically averting the gaze of the camera.

It is because there is the question of, their identities and the fact that, their families may not approve of, their visibility in photography, and especially that once the photograph is taken and its out there for public consumption that’s it. There’s no way to control where the photograph is going to be.

So basically the absence of facial identity within each portrait creates that distance between the viewer and the sitter?

Yes, I mean, for them this is how they’ve negotiated with it. They wanted to participate in this project, however; this is how they negotiated their visibility, by not, revealing their identities or basically obscuring their faces.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Were they conscious in front of the camera compared to them being in their own personal spaces?

Well, I don’t think they were, I mean they were quite OK with being in their personal spaces. And the fact that, I gave them basically the green light to appear how ever way made them feel comfortable, eased the tension.

I think they were appreciative of that, I don’t know, I didn’t really pressure them to appear in a certain way.

Did you create still life images in order to show the audience that the connection these women have with their Saudi background is still very much in existence, or do you think it was a coincidence?

I, this was one of the things that I looked at, and of course, this comes in various degrees. Some of these girls actually even maintained their dietary habits in Saudi Arabia, and some didn’t, some girls chose to smoke the hookah, in their homes.

And it, for me it was really interesting, the various degrees of how these girls want to reproduce the same habits, the same consumption habits that they had in Saudi.

There is a window present in most of your portraits, so this could be interpreted as a reference to the restriction women experienced in the Saudi Arabian culture. What was the intention?

For me I, I mean the idea, it wasn’t really—I mean for me it was a bit more optimistic than that. It was more about the window representing possibilities.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Having a window in the background was intentional?

I mean for me the window is quite interesting, because it’s the beginning of something. I do believe, I mean, based on what a lot of the participants told me, which is getting on this scholarship program, is a—was an incredible experience, an incredible opportunity for them.

It’s like the beginning of, of something, and that their lives had significantly changed since this experience, and I, and for me I think the window represents this-the beginning of something that’s positive.

And were you also looking at other metaphors?

I mean looking at, when you look at old Dutch paintings, there’s always something, like the motif of the window and, the women being by the window. I mean, I see what you mean about how this means ‘imprisonment’.

But somehow for me, as you noticed, there’s always really strong light coming from the window, like something emanating, so I would hope that it could also mean something else, especially as all the windows are quite big in the portraits. So perhaps it could be a way for them to, not necessarily escape, I mean I don’t want to use the word escape because escape would mean that they all come from tragic or from tragedy…

But this could be just going to a different phase, or, like, a different experience perhaps.

Do you find it encouraging that many of these women are willing to participate and present themselves in a way that isn’t considered normal within their culture?

I was really pleased with the level of participation in the work, I mean, despite I get a lot of people asking me, ‘Oh we don’t see, we can’t identify with these women because we can’t see their faces’, but I just think that’s such a superficial question. Do you know what I mean, I feel like, when somebody asked me that question that they completely missed the point of my work.

Just like I said earlier on, I do believe that, hopefully, the more I continue working on this project, the more it will, you know, I think the rapid social developments that are happening in Saudi Arabia, the openness the people are experiencing, I think will also show through the way I will be able to take the women’s portraits.

Did you also have a preconceived notion of how this project would work and the way the viewer might interpret the lives of these women? You just mentioned, for instance, that a lot of people keep asking why the faces are not visible.

I know, because I think people are used to certain ways or certain tropes within the genre of documentary photography—I would say there’s always some specific type of pose for the portrait, specific type of environmental portrait, do you know what I mean, and I don’t think my work necessarily fits in.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Your work has a really strong social political statement; it’s not just a portrait series.

Yeah, it’s, this is what I would hope. I don’t want, I mean, I think my main goal is to create a body of work that’s engaging and thought-provoking.

And I want people to actually get drawn to the photographs and look at all the details.

Wonder about how these women conduct their lives, and how much it took for these women to reach this stage and be appreciative of that. This is I think what I really, really wanted.

Looking at your other bodies of work, with that feminist approach in mind, would you give us an idea what the situation for women in Saudi Arabia is right now?

I think that women are already emerging in the public realm.

Try and think of something that is very interesting, I think more and more women are participating in the labor force. Maybe not as much as we would want them to be, but I do think, because I was just back there a couple of weeks ago and I was really amazed by how many girls are, let’s say, choosing to be, just start their own businesses, there is this consciousness of you know, women basically wanting to not rely on anyone else to take care of them. So that’s a good thing, so at least mentally they’re prepared to become more and more independent. Even if it was just starting to be financially independent, I think that’s an important thing. Obviously there are some setbacks with regards to, women not being able to drive, the aspect of mobility obviously it is important, but I think this thing will hopefully come soon. I hope because it will relieve a lot of the, economic setbacks that, hiring a driver or, whatever, would cost, because it costs a lot of money. I think before anything, having someone to drive you around is, it takes a lot from your personal budget. So for me, I think with whatever is related to my work, I’m more interested in how women are becoming not really visible in the public realm, but it’s actually normal for women to be visible publicly. For example now, I think it was last year, or the year before, there was this huge controversy about women working as cashiers at supermarkets, but now it’s absolutely fine.

People just got used to it. So for me, this is what I’m actually interested in. So in a sense, it is a departure from me focusing on the private space.

But I think the one work I want to look into right now, and I think hopefully I’m going to start doing that in the spring break, is to start tracing how women are taking over the public space.

I’m amazed by the amount of artists that are coming out and giving really strong statements, regarding the public norms that exist in the country. Something that you recently mentioned about that cashier incident. So do you think various mediums of art is also playing a part, and is considerably becoming really important in terms of expressing?

The thing is, the good thing about the art, or producing something that is socially critical, for example, under the banner of fine arts is, it enables you to be able to, provide social criticism.

It’s a safe way, rather than let’s say you, I don’t know, writing a column in a newspaper, which I think is really incriminating.

Or even a Tweet.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

I was just reading an article about Suad Al-Shammari; she was very seriously threatened just for tweeting about beards, you think it’s still a male chauvinist society?

I think it is very patriarchal, I mean, it is in a sense, but I think it is because it hasn’t happened before. So people are a bit shocked. By women, like this woman, actually voicing her opinion or objecting to something. But, I do think they will adapt to it at some point.

So you think women are becoming much more expressive as well?

But women have always been expressive in the public media.

In terms of the visual art, this is something that has been going for the past a little over ten years, but then women have been expressive in other ways through literature and writing, and this has been going for the past two decades, three decades. But then again, this has been, it is quite an elitist thing, do you know what I mean?

Now I think the good thing about the way the arts is developing in Saudi Arabia, it’s encompassing different types of people from different backgrounds and different levels, and different understandings. So I think maybe the arts is becoming more accessible to everybody.

So how easy or difficult was it to showcase your work during Jeddah Art Week. Are these organisations being open about showcasing important yet controversial art medium?

I was, I mean, I don’t think there’s anything controversial about what I showed in Jeddah Art Week, but then again bear in mind, the portraits were not displayed in Jeddah Art Week. I think if the portraits were displayed in Jeddah Art Week that would of probably, I’m speculating here, that might have caused a stir. But the photographs that showed at Jeddah Art Week were just the veils and the Still Life.

So, I do think that people with initiatives—like Jeddah Art Week and all the private galleries that are opening right now—they’re playing a very important role, is that they’re making people accustomed to various forms of visual material which is great, but I do think gradually women will be able to. I mean, I wouldn’t be surprised if Manal would be able to show her project Crash in Saudi Arabia very soon.

Because I do think it’s a very valid question that she is posing, with regards to, you know, the unnecessary deaths of these women who are basically just going to their jobs. So we’ll see, I mean, I prefer to be hopeful and optimistic. I think when it comes to being in a context like that, it’s good to try and not, obviously you want to push boundaries, but you want to be sensitive as well because you don’t want to cause backlash, because when there’s backlash there is so much time wasted to calm them down.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Considering what you mentioned, how was the local response to your portraits and the images that were displayed at Jeddah Art Week?

It was very interesting. Except, there was this one work portrait that did cause a lot of stir, and someone from the organisers just isolated that image; it’s the portrait of the Quran from the Casablanca film where the couple are embracing.

And, so this image was basically isolated and presented in the Instagram account of Jeddah Art Week.

And obviously somebody started with a comment, saying that this is disrespectful to the Quran, and they got really, really upset, so many people joined in the critic and it suddenly became a religious matter.

And I worried, obviously, because it just got a bit out of hand because people were reading too much into it and I—

It’s not that I didn’t want because I was really shocked that they got offended by it because, I did not see that connection that they saw.

And I didn’t see how this could be religiously offensive, and it just became a matter of how could the photographer allow such a thing to happen, but then again I got a lot, I felt that because that image was isolated from the surrounding images, just to give it context. I think that was one of the reasons why the reaction became as focused on that and did not look at the holistic work and I asked for, the person who uploaded the image on the Jeddah Art Week Instagram account to take the photo down, because I told her next time, if you’re going to show the work, show it the way I presented it, which is a series of images together, because the way I presented it was like a constellation of 26 images.

And I told her, I’m really grateful that I got to show it in Saudi Arabia, I don’t want this to be the last time I get allowed to show my work there.

I noticed the Arab News quote that your work “is an interrogation of the stereotypical representation of women from her native country”.

Is that what they said?

That is what they said, what do you think about media support in terms of the project, considering the controversial remark on the situation of Saudi women in their native country and abroad?

Yeah, well, I didn’t read that comment by Arab News.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Well this is what they said, and it was really interesting. It was really interesting to see, how the media is talking about your work in Saudi.

I mean, it was just a comment like that. I don’t know whether they actually understood the project. I mean nobody called me up, let’s say, and requested more information about my work.

But that was fine, I mean for me I was just really grateful that I at least got to show it in Saudi Arabia. For me that is a huge step, because particularly, as I mentioned earlier, I do want to continue working on this project in Saudi Arabia, so this is a great introduction for me. So people are now familiar with the type of work I create and the subject matter. So hopefully, fingers crossed, locating more participants in Saudi Arabia should be, I would hope, easy.

I’m still a little curious about this quote, “interrogation of the stereotypical representation of women from her native country”. What do you make of this?

To be honest with you, I really don’t understand what they meant. What do they mean by, like, stereotypical images of my country? (Laughs)

Because you know it’s—so, are they, are they saying that I’m not presenting something stereotypical?

I mean yeah, the stereotype of Saudi women, you could just go to, I don’t know all these image banks, Google images, and just put Saudi women, and you’ll see the stereotypical images.

I don’t think that it is stereotypical at all.

Not at all, but I mean it could be just not—I think it’s probably just not written that well, or they just completely misunderstood my work.

Do you think the media has also been outspoken about such projects? Even if they’re writing and commenting about it, do you think media there is opening up, or is it still very controlled and biased?

I mean, you know what, with regards to this, I don’t think it’s about being controlled or biased. It’s just that there are highlights, let’s say, from that show or bigger names from that show so the main focus was on, basically the highlights of the show.

And obviously you do have, there is a hierarchy, and I think they have just followed that hierarchy. I don’t think that they, that there was a, like a political decision to describe my work in that way. I just think that whoever wrote it, completely misunderstood my work, and didn’t bother.

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Do you think that situation might arise once your work is shown more extensively on a much bigger platform within Saudi?

Perhaps. I mean I do think the media is bolder right now, and I don’t think there is an interest when it comes to women’s issues. I mean for example, I don’t know whether you’ve read the article on appointment of the new woman editor at Saudi Gazette. The fact that the main editor of the established newspapers in Saudi Arabia is a woman.

It’s a big thing.

It is a strong statement. So this is in a way, an indicator that things are changing, albeit very slowly, but they are. And for me it’s good, I think because, well, me being born and raised in Saudi, I know. Maybe for people who are not really familiar with the Saudi context and they’re used to a different pace they can be a bit unsure but, because I come from there, and I know this is a huge step.

It is a good thing.

I noticed the Art Week happens under the patronage of Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Culture and Information, and Abdul Latif Jameel Community Initiatives. You mentioned the debate around your image—so did you hear anything from the government body? Did they react to you work?

No. No, not at all. I think they were quite supportive, the organisers. I mean the fact that they’ve spent so much on an initiative like this, and this is the second time they do Jeddah art week I think.

I think is incredible.

Do you think up till now it’s been a very elitist art scene that’s been coming up?

Actually, no, right now you have an emerging art scene that is starting from Saudi, but we need more.

We need more, but I think these initiatives are doing just that, at least three or four times a week, I get emails about workshops, opportunities for artists in Saudi, artists of various forms, applying for funding, yeah, it’s incredible, it’s incredible. That’s really great, I mean this wasn’t the case when I started, which was what, like, in 2004, so it’s great.

As one of the last questions, what is the impact that you want to leave on the society with your project?

I think for me, I would like, I would really like to just widen the debate on Saudi women, and introduce a different discussion. Which is basically, let’s talk about those who, don’t necessarily tick all the boxes, what happens to them? And what it means to be—

Image©Wasma Mansour

Image©Wasma Mansour

Can you just give me some references to the impact, to the debate, the discussion?

I don’t know, the fact that, I mean, obviously it’s, the work itself at least allows people to start thinking about women who do not, who are not the stereotype of Saudi women—which is the woman who at a particular age is married and already has a family. For me that is my contribution, let’s say, to knowledge on Saudi women, that they don’t all, you know, fit one description. They come from different trajectories and they have different experiences, and obviously these experiences have influenced how they choose to conduct their lives, so yeah.

So, Wasma, what is the next step? What are you planning to do outside of the UK now in terms of your project, Single Saudi Women?

Like I said, hopefully in Easter I’m going to start looking at, basically, how Saudi women are emerging in the public sphere in Saudi. So it’s quite interesting how in the UK I’m looking at their private spaces, and in Saudi Arabia I’m looking at Saudi women in the public sphere. I think that would be a really interesting juxtaposition.

Photography Research by Megan Blackwell