Emaho: Can you take us back to your early life in Iran – what first drew you to photography, and how did your surroundings shape your initial relationship with the camera?

Reza: I came to photography around twelve / thirteen years old, not because of art or dream worlds, but because I was seeking a means to show the beauty of everything that was giving me the emotion, from nature to the humans to the building to the objects and the same emotion that i was getting by seeing social injustice, poverty, and misery I witnessed during my childhood in Tabriz. I wanted people to know about these beauties and realities, and photography became that voice.

At thirteen, I took my first photograph, and at sixteen, I published a high school magazine called Parvaz. I was arrested and beaten up. At nineteen, I secretly displayed my photographs on the University of Tehran grids, placing them on public walls to share stories that couldn’t be expressed any other way. This act of artistic activism led to my arrest at twenty-two. I was imprisoned for three years and tortured for five months.

My relationship with photography was shaped by necessity and resistance. Iran under that regime was a place where visual truth-telling was dangerous but essential. The camera became more than just a tool – it became my weapon against injustice, my way of capturing what officials wanted hidden.

Emaho: Was there a specific moment, image, or experience when you realized photography would become more than a tool – but your way of engaging with the world? Who has been your favourite photographer?

Reza: The defining moment came during a student demonstration when I was studying architecture – army jeeps surrounded the demonstrators, soldiers came down and started shooting. I saw one student running with a camera, taking pictures while looking to protect himself. That image of courage changed everything. I asked for three days’ leave from my architect’s office. The next day, I was on the streets photographing, and day after day, I just forgot to return to my office. That was 46 years ago – I still haven’t gone back.

During the Iranian Revolution in 1979, I gave up my career as an architect. I turned fully to the camera, witnessing how people living through history have their own distinctive ways of seeing things.

Regarding favorite photographers, the truth is that i have not seen any magazine, any photography book, nor any professional photographer to learn from him, i am fully hundred percent autodidact, and it was during the revolution in the streets that i met many of the professionals that i did not know them, Marc Riboud, Olivier Rebbot, Abbas, and many more, i was very astonish by the way that they were photographing. My influences seem to come more from lived experience and the subjects themselves than from studying other photographers’ work.

Emaho: Your work consistently bridges journalism and deep human empathy. How would you describe your fundamental purpose as a photographer – is it bearing witness, storytelling, advocacy, or something deeper?

I tell stories of human beings trapped in the turmoil of the world through the universal language of photography. If I am in a war zone, it is not because I want to photograph the war – I am photographing what the population is suffering because of the war. This is my contribution to the future.

The camera is the most powerful tool ever invented – it is more powerful than any weapon, because its strength comes from empowering people and multiplying their potential. Photography is the biggest revolution ever – we don’t have any other universal language but photography.

My purpose goes beyond witnessing. My images do not give only a sad report of shattered lives – they also testify to the smile behind the tears, to the beauty behind tragedy, and to life, stronger than death. I am not a war photographer but a peace photographer, a peace correspondent, helping to shed light on the individuals and communities affected by conflict.

Emaho: Your images span decades and continents. Are there particular projects that stand as defining chapters in your career – ones that changed the way you saw yourself, or the world?

Reza: Several projects mark defining chapters:

First in Iran under the Islamist government, when immediately after taking – confiscating – power, they attacked most minorities and committed massacres of Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Baluchis, and intellectuals, I was sometimes the only photojournalist able to get in and take photographs that were published in the international media. The reason I had to flee Iran was that the Islamist regime discovered I was the author of most of those photographs.

In the meantime, I covered all hostage taking in the American Embassy of Tehran. During the Iran-Iraq War, I was wounded on the frontline.

Then, during the summer of 1982, the siege of Beirut became the moment when my coverage gained international attention through Sipa Press, a Parisian photo agency, and Newsweek Week, for whom I started working in Tehran during and after the revolution. Chemical bombs, probably phosphorus bombs, injured me, and I was evacuated to Paris.

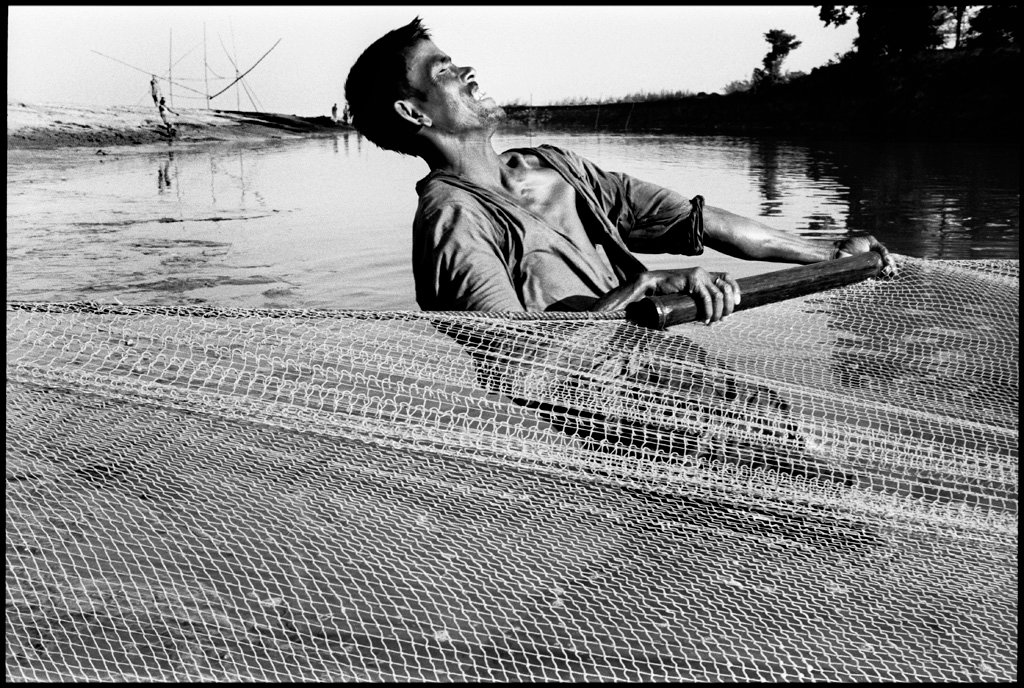

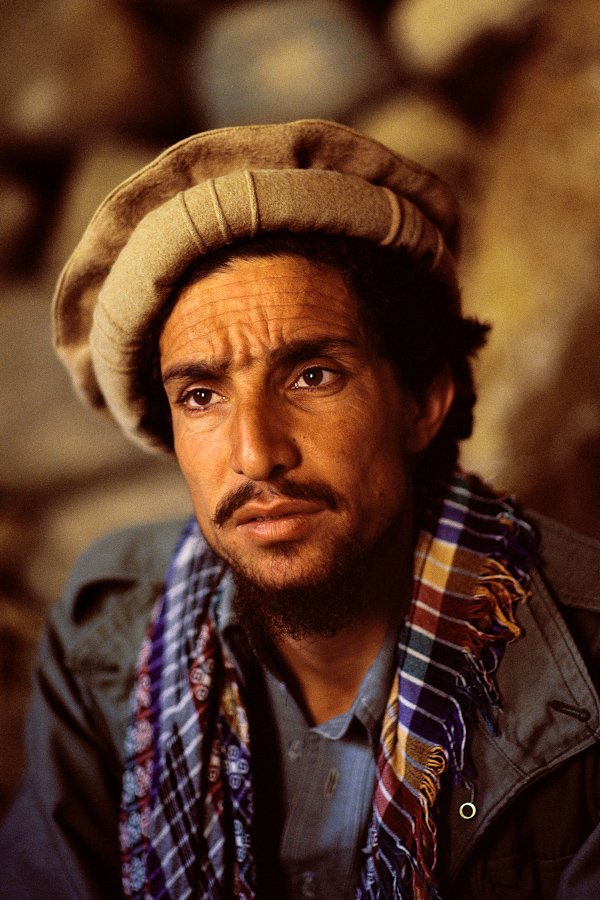

One of the most important stories was about Afghanistan under Russian occupation. I walked hundreds of miles through the mountains in secret, clandestinely. I brought out a few major stories from deep inside, including a significant story about a young commander in a valley. Later, he would become the legendary commandant Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Lion of the Panjshir Valley.

Black January (1990): When Russian tanks rolled into Baku on January 20, 1990, I traveled from Paris under the pretense of filming a ballet in Moscow, then made a dangerous 48-hour journey hidden in a train to reach Baku, which was under Russian army siege, to document the massacre. At a time when walking in the streets was dangerous, surrounded by Soviet tanks and patrols, I risked my life to secretly capture photographs. This is the kind of work that, as a person driven by the truth, you have to do.

Khojaly Massacre (1992): During the Armenian-Azerbaijani war over Karabakh, I heard that the population of one Azerbaijani village was massacred on the night of 26 February 1992 by the Armenian troops. Hearing the news, I immediately traveled from Paris to Baku, making contact with Médecins du Monde and traveling to Agdam, where we saw people bringing dead bodies that were killed in a very terrible way – mutilated. Those images are hard to turn away from – the trauma runs to the core.

Rwanda (1996): After witnessing the tragedy and massacre of hundreds of thousands of people and refugees, I helped UNICEF and the Red Cross continue a photo-tracing project with portraits. Pictures of 12,000 Rwandan children who lost their parents during the civil war were exhibited in five refugee camps, and people who had lost children came to the exhibition, looking through the photographs to find their loved ones. At least 3,500 children were reunited with their families. This showed me photography’s power to heal, not just document.

Afghanistan and Aina: In 1991, I served as a UN consultant in Afghanistan, launching large food-for-work projects to rebuild infrastructure destroyed during the war, rather than providing free food to war-torn populations. Later, I founded Aina, the first NGO to teach locals, train them, and produce all media in 2001, demonstrating that photography could empower communities to tell their own stories. This included creating the first women’s magazine, the first children’s magazine named “Parvaz,” the first radio station for women, Afghan women’s voices, the first female photojournalists, videographers, and mobile educational cinemas.

Emaho: The Massacre of Innocents is a powerful and important photobook. What was the emotional and ethical journey of creating this work, and what do you hope readers carry with them after engaging with it?

Reza: With Rachel, a French writer and my life companion. We have authored over 40 books spanning various stories and themes. I have visited more than 115 countries. Since 1987, when I first traveled to Baku, I have returned to Azerbaijan multiple times as a photojournalist, covering Black January in 1990, the Armenian-Azerbaijani Karabakh conflict, and the Khojaly massacre in 1992. In every village, town, and city I explored, I saw memorials honoring tragedies—I wanted to pay tribute to these women and men, all powerless victims caught in the geopolitical struggle.

On Azerbaijan, We published two books:

“The Elegance of Fire” showcases the people of Azerbaijan, the landscape, culture, and traditions, and “The Massacre of the Innocents,” the suffering from Black January, the Karabakh war, and the massacres. It’s very important for me that the world knows both sides of life, beauty, and suffering.

Emaho: Your practice includes both on-the-ground photojournalism and curated exhibitions. How do these forms – book, exhibition, print – serve different purposes in your work and in audience engagement?

Reza: There are as many ways to tell a story as there are media – press publications, web-documentaries, exhibitions, installations in public space, documentaries, books, and conferences are all complementary means of talking about a subject I am witnessing.

As an architect, I have always aimed to integrate photography and cultural elements into public spaces. In 1998, I first installed an exhibition called Mémoires d’exil in a public space at the Carrousel du Louvre, starting a long series of original installations outside museums. This approach allows everyone to engage with visual art and information, not just museum or gallery visitors. My key installations—One World One Tribe in Washington DC, War+Peace at the Caen Memorial, and the giant panorama A Dream of Humanity along the Seine—reach hundreds of thousands, even millions of people. My landmark exhibition in Paris, the Sénat’s Crossing Destinies, drew a million visitors. Over 370 exhibitions across many countries and continents best demonstrate my passion for art in public spaces. Books offer permanence and depth, while exhibitions foster public dialogue. Each medium serves the story in different ways, reaching diverse audiences with the core message of our shared humanity.

Emaho: War, conflict, displacement, humanity – your themes are both wide-ranging and deeply rooted in lived experience. How do you navigate the tension between documenting reality and creating a visual narrative that resonates emotionally?

Reza: To me, there’s only one factor that makes a photograph good or not: whether it captures something happening in your heart before anywhere else in your body. If it touches your heart, then for me, it’s a good photo, and it can communicate what you want to say.

When I experience a story, everything I see around me—every unique story, every single picture—the first question that comes to mind is: Does this sense match my thoughts about the story? Is there meaning in these pictures that can shed light on the whole story? Ideas come first.

I realized long ago that anyone can take a shocking picture of corpses, darkness, or suffering, but what does that add to the world? It creates a barrier between the viewer and the subject, making them shy away instead of engage. My photos show the human element of suffering—the living individual amid the destruction—because we must look beyond the dead and find ways to connect with and help those who remain.

There is more horror and emotion in the eyes of the survivors who look at the destruction and death in front of them.

Emaho: You’ve witnessed many conflicts firsthand. How has your perspective on war and peace evolved through your lens, and what role do you believe photography can play in shaping how the world understands them?

Reza: My very first observation in conflict and war zones led me to reflect: there are two kinds of destruction that occur in all disasters from war and conflict areas—material destruction and the destruction of the human spirit. Most UN work and other NGOs, especially 40 years ago, focused only on rebuilding the material damage, and nothing was done to help people recover from trauma. While in Europe and Western countries, every disaster brings in psychotherapists to assist people, I had to ask: What about the entire Afghan nation, Cambodia, Rwanda, or other Middle Eastern populations who have spent their lives under threats and bombardment?

Throughout history, warfare often occurred without witnesses, leading to devastating massacres and massive loss of life. Photography helps bring witnesses to the reality of war. For me, the solution is to develop media and communication tools for them and to train and educate local people suffering from war so they can express themselves.

Afghanistan. Vallée du Panjshir. 1985. Portrait du commandant Massoud (1953-2001) pendant la guerre d’Afghanistan (1979-1989).

Emaho: Photojournalism itself is changing rapidly – from AI and digital platforms to citizen reporting. Where do you see the future of photojournalism heading, and what remains timeless about its core mission?

Reza: The camera empowers people and amplifies their potential – it is a tool that speaks all languages and can connect its user with everyone around the world, allowing each person to share their story and unique perspective.

This democratization through technology – whether via smartphones or new platforms – aligns with my work training refugee children and youth worldwide. Through Reza Visual Academy, passive victims become visual witnesses and, ultimately, active participants in shaping their own future.

What remains timeless is the human heart behind the lens. Photography must first touch the heart. No technology can replace the empathy, lived experience, and commitment to justice that drive meaningful photojournalism.

For now, AI is a tool, a very powerful one, just like the airplane was for early 20th-century travelers. We need to learn how to use each tool most effectively.

Emaho: What ethical considerations guide you when photographing trauma, suffering, or communities in crisis – particularly when the world is watching images at such speed and scale?

Reza: Being an exile from Iran has given me a completely different way of connecting with the people I meet. I understand the suffering, and when I am in refugee camps, when I photograph the refugees, I truly understand who they are and what they are going through — and that’s what you can see in my photographs. I have never experienced a moment in my life when I feel nothing – every single moment is filled with passion and love. Many of the photographs you see, believe me, I have taken with tears in my eyes – some of them I haven’t even seen clearly, whether they’re focused or not, because there were too many tears in my eyes.

There was a moment in Sarajevo when snipers were shooting everywhere – I saw a little girl, maybe nine or ten years old, standing against a wall. When I asked what she was doing, she said: “I’m selling my dolls because my grandmother is hungry, hasn’t eaten for four days.” This might be more heartbreaking than many other scenes because it shows how war pulls people back, creating not only destruction but also trauma. These moments require us to photograph with dignity, understanding, and awareness that we are documenting someone’s deepest pain – and that we have a responsibility to that person and to the truth.

Afghanistan. April 1983. An old man sitting on a bench is reading Koran near the Pakistani border. He is a refugee fleeing the Soviet invasion with his family.

Emaho: Over the years, how have your interactions with the subjects of your images influenced how you see humanity, resilience, and the collective human story?

Reza: My photographs are the testimony, and serve as evidence of the chaos of war, its destruction, and the helplessness of people caught in the storm – but they also reveal the world’s cultures, traditions, history, and most importantly, my unwavering hope for a better world.

Their experiences stand as a testament to the remarkable progress that can be made even in the face of adversity, emphasizing the potential for growth and development in all of humanity. Their resilience sends an inspiring message, especially for those who welcome them into their new environments, showing the mutual benefits that come when societies effectively integrate and support refugees.

When you delve deeply into the brutality of humanity, if you stay there long enough without finding something that could help you escape or understand it, you might become one of them. For me, the best way to refine my soul is through poetry, reading poetry, and loving flowers. When you realize the impact of your images and your work on people, it also gives you the strength to withstand the trauma of what you have experienced.

Every face I’ve photographed has taught me about the resilience of the human spirit.

Emaho: Looking ahead, are there themes, stories, or places that you feel compelled to explore next – and what keeps you driven as a photographer after so many years in the field?

Reza: Through “Reza Visual Academy,” I have expanded my training and teaching in photography by creating two international photography contests for children and youth. Using their passion for photography and participation in these contests, I aim to guide them to engage with nature, history, people, culture, and environmental issues. Through “The Children’s Eyes on Earth” and “Youth Lens on the Silk Road” with UNESCO, I am encouraging thousands of children and youths to use photography to connect with the world. The theme “I Love Nature, I Fear Pollution” is an excellent way to help children connect with and understand the beauty of nature and the importance of preserving it because, ultimately, we defend what we love!

Through a youth perspective on the Silk Road, it offers another way to connect young people to history, tradition, and culture.

I was so happy to see the photograph taken by an eight-year-old Russian girl, who was the first winner of the photo contest—an outstanding piece of photography that many professionals, including myself, wish we had taken! This reveals what motivates me now: empowering the next generation of visual storytellers.

The goal of “Reza Visual Academy” is to implement photo-training workshops for youth living in vulnerable communities worldwide, such as refugee camps or disadvantaged suburbs. Photography is used as a tool to empower local actors, helping them become informed and capable of self-expression, which in turn promotes self-esteem, self-sufficiency, and the development of stable, peaceful societies.

Convinced that the language of images can inspire resilience within vulnerable communities, I have been teaching in this medium since 1983.

My recent work includes “The Valley of Knowledge” exhibition at the Pantheon in Paris. What keeps me motivated? The same reason I was drawn to photography at age twelve — the belief that revealing the truth to people and empowering them to tell their own stories can help create a more just and peaceful world. Photography is the greatest revolution ever, and we are just beginning a new era where images and photography will play a crucial role.

Photography by Reza Deghati