U.S.A. –

Rachel Seed is a Brooklyn-based photographer and filmmaker who divides her time between multimedia documentary projects and freelance photography assignments. In her latest work, A Photographic Memory, she sets out on a journey to learn more about her mother whom she never knew but so desperately needs to know. She is the daughter of New York and London-based writer, editor and producer, Sheila Turner, who passed away while Rachel was only 18 months old. She revisits her mother’s half-finished 1970’s landmark project Images of Man – a series of interviews with legendary photographers – and combines it with her own footage, to create a posthumous mother-daughter collaboration. In this conversation, she takes us through her journey of making this unusual film.

Some years ago you discovered tapes containing interviews with legendary photographers that your mother had been working on. How did the idea for a film fall in place for you and why did you decide to take a personal approach to the film?

At first my idea was simply to have my mother’s series, Images of Man, digitized and re-released for current media. But as I began to discover how much of herself she put into the programs, and how much of a story was around the work, I got the idea to broaden the project and make it more personal. As a journalist/photojournalist I was much more comfortable behind the camera, so it has been a real stretch for me to be in front of it.

“Images of Man” envelope when it came out.

What did you feel when you first heard your mother’s voice conducting these interviews?

Her voice was familiar to me and comforting. I wasn’t expecting that—I thought it might be creepy and disturbing to hear her voice. She sounds warm and loving, even in the interviews. She was a very compassionate person and this comes across.

‘A Photographic memory’ must have been as much a journey about your mother as it must be a journey of self discovery. Can you share with us the nuances of this journey and how has it affected you as a person & as a filmmaker?

I often joke and tell people that making this film is Art Therapy for me. The wonderful thing is I have an excuse to have long conversations with everyone who knew my mother. It’s a chance to get to learn so much about her, and to connect with the people who knew and loved her and whom she knew and loved. As a result, I know much more about where I come from, which is empowering and grounding.

Contact sheet of Sheila in her NYC apartment

About your mother’s film project, Brian Lanker notes on his website that participation in the series is “his greatest honor”, something he ranks above his Pulitzer Prize. What have been your impressions of your mother and her work? Can you describe to us the importance of the project she was working on and the role she played in it?

So many people have told me how the programs she made enlightened them and improved their lives. They are really special, even all these years later. I think that’s how good art is—it resonates long after it’s made. My mother was smart, original, creative, warm, and persistent. And she was a perfectionist, which was one reason she drove herself so hard, and this may ultimately have led to her death. Images of Man was her idea, which she produced with the support of Scholastic and Cornell Capa and his Fund for Concerned Photography. It was an important project because it introduced a generation of students to photography and what inspires photographers to do what they do.

Sheila Passport Copy

In A Photographic Memory you blend your mother’s 1970s interviews with your own footage, creating a posthumous mother-daughter collaboration while re-examining the careers of some of the most influential photographers in the history of the medium. How did you balance the two objectives? What according to you is the role the film will play in documenting the works and vision of these photography greats.

Both themes are interwoven—photography helps us capture and preserve memories, and my family history is very much enmeshed in photography as a career, practice, and way of life. My mother’s best work was about photographers; she also took pictures. Cornell Capa, founder of the ICP, introduced my parents to each other, and his life was all about photography. My father is a photographer. Etc. The primary story of the film is about reconnecting with my mother and focuses on who she was, but through that, the audience will learn about several photographers and their work, since that has been a central theme in our family history.

Bruce Davidson said that your mother and you shared the ability to “make him say outrageous things”. What does a compliment like this mean to you?

I felt very connected to my mother when he said that. I love the idea that my mother and I would have similar interview styles. At the beginning of her interview with Cartier-Bresson, there is a part where she does a test. When I first heard it I thought it was me talking. It also means a lot to me that she connected so well with Davidson, since he is one of my favorite photographers.

People must be tempted to draw parallels between you and your mother. Do you also feel A Photographic Memory is a perfect way to establish your own vision as an artist, different from that of your mother’s?

This is not one of my concerns. I’m not even sure my mother would have called herself an artist—she was most concerned with getting good, honest, intelligent, real stories. She happened to be an amazing editor, interviewer and ideas person. I would call her an artist, but there was no pretense around what she did. She just loved humanity and was hopeful she could make a difference by helping people learn about things she deemed important. I am different in that I am a photographer first, and I love both conceptual and documentary work. I don’t really know how she felt about conceptual art.

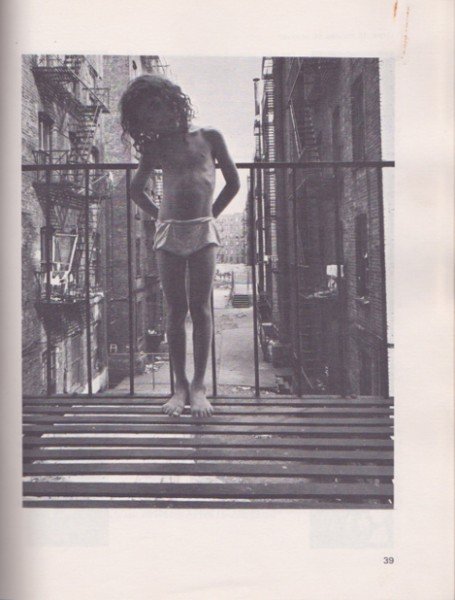

Images of Man © Bruce Davidson

Can you share your experience interviewing Don Mcullin, who refused to give you an interview and did so much later? What were the other challenges you faced in putting this film together?

McCullin was certainly challenging to meet with. He is a great person to interview, full of salty charisma and contradictions. He refused to be interviewed at first, but told me he’d be in Houston for his War/Photography opening at MFAH. I flew there with no interview booked and attended his talk. Later he agreed to half an hour, which was generous of him considering what a busy weekend it was for him.

The challenges for this film have been getting interviews, fundraising, creating a story that speaks to people and makes sense, and hiring and directing a film crew (for the first time).

We were very fortunate that Richard Robinson and his company, Scholastic, generously offered seed money to start the film in 2011. This was vital to begin production and planning. As a photographer life is much simpler and you don’t depend on so many others to bring a vision to life. In film, you need to find people you really trust to make it happen. It’s my first time directing so it’s been a learning experience.

Interviewed by Akanksha Gupta

Interview with Bruce Davidson by Rachel Seed

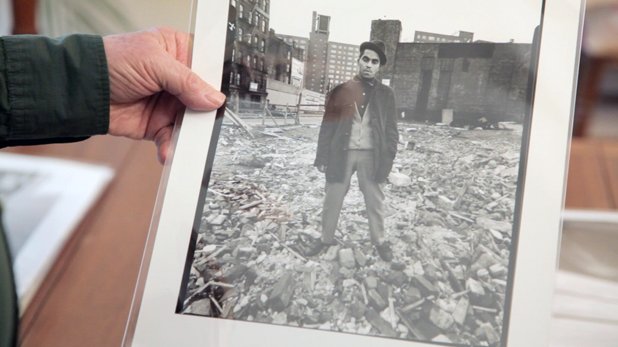

In May, 2012, I spent a day with Bruce Davidson in his Upper West Side home and photo studio. Forty years earlier, my mother, Sheila Turner-Seed, had interviewed him in the same apartment, for a series she created with International Centre of Photography, New York’s Cornell Capa and Schoalstic, Images of Man. These excerpts below are from that interview. –Rachel Seed

Rachel : What is it about finding the other side of things that’s always driven you? For example in the circus you were photographing the outside of the circus. In LA you are not photographing the inside, you are photographing the outside of things.

Bruce : I think I am particularly prone to photograph that which is in transition. In terms of the Brooklyn gang series these are young people in their traditional part of life and they’re transforming themselves. They are full of vitality and depression and all kinds of things are running through a teenagers mind at the time. And I captured that, I felt that. I felt their aloneness. I liked them, you know. I wasn’t one of them…

Rachel : About Los Angeles, you were saying that you’re photographing the back of the Hollywood sign and the plants that are under things and it seems a thread throughout all of your work is you’re looking at the outside of things, or the inside of things. So I’m curious if you could talk about that a little bit.

Bruce : In the case of being behind the Hollywood sign, it wasn’t only being behind the Hollywood sign, but it was the Hollywood sign in relation to the desert and from that vista I could see that LA is really in a desert: the arid, scrub, desert. And the … sign just framed it for me. Brought me closer to something that is not usually observed that way. People come to see the sign and they only see the sign. From a certain distance too.

There has to be some sort of tension, some sort of reason, something that draws you in and I have to be ready for it, to see it, to feel it, to understand it

Rachel : How are you ready for it?

Bruce : You go out every day with a shovel and you keep shoveling the coal.

Rachel : But what is it about your personal experience that makes you attracted to those kinds of things?

Bruce : I don’t know what draws me to various projects and ideas. It just comes. And it comes because I’m staying open. And also I think it comes out of the passion to photograph. Photography is a passion to me. I don’t think I could live very long without taking pictures. And the pictures then take me.

Rachel : And it’s always been that way for you?

Bruce : Yeah. I think it’s always been that way. Going from the outside to the inside and then outside again. I’m kind of a black hole.

Rachel : You’re a black hole?

Bruce : My magnetic life draws me into a whirlwind of space and time. So I’m kind of an astronomer.

Rachel : I’m curious about your experience being a part of the Images of Man series, which was 1971-72, that time period. I’m curious what you remember about Sheila.

Bruce : Well I felt that she was very warm. Very open, and very warm. And I also thought that her voice was very beautiful. Just her normal conversational voice was very attractive…. And I remember being open to her. She could have asked me any question, and I might not have an answer, but I would listen to what she had to say. And then I … remember her smile, which is broad and open. I didn’t know her well, she just came over for a few hours one day.

Rachel : And did you keep in touch after?

Bruce : No. You know at that time, being interviewed was unusual. I wasn’t as sought after in any way. I did it probably because Cornell asked me to do it. I didn’t know what I was getting into (laughs).

Rachel : Your work could be interpreted as journalistic, or documentary, or art. I’m so curious– Which of those do you consider yourself: an artist, a journalist a documentarian?

Bruce : I’m not a fine art photographer. I’m a fine photographer. That’s enough for me. I think what has happened to photographic art is it’s become part of business. It’s about business. And you can’t stop that, the galleries and museums are predicated to making money. So you have to stay away from all that and just do what you do.

Rachel : What do you think about those differentiations between documentary photographer, photojournalist, fine art photographer, does any of that matter?

Bruce : It doesn’t matter to me. I touch all of it. There are photographs I’ve made that are in museums as fine art, there are photographs I’ve made—maybe sometimes the same photograph—that are printed in the magazine of a newspaper for some reason. There is an art market, and it’s growing. My photographs have become so expensive I can’t give them to anybody anymore. (laughs) Forty years ago I would give a print as a birthday present but I can’t get away with that now. I can’t make that many prints. Things have changed. And yet—the passion and the purpose that I find in photography, hasn’t changed.

Do you know Hugh Edwards? Hugh Edwards was the curator of the Art Institute of Chicago. He first showed Danny Lyons gang pictures, and he showed my Brooklyn Gang pictures. We were walking on Michigan Avenue, and he’s crippled—he has crutches. And he stopped, he said, “You know, Bruce, art can be anything, but it usually isn’t.” You know? And I think that’s true. There’s a lot of monkeying around

Rachel : (laughs) So, explain what you think that statement means.

Bruce : I’d say it means there’s an awful lot of visual garbage out there. And that the real photographers are poets. The Robert Frank’s, the Gene Smith’s, the Cartier-Bresson’s, the Brassai’s… They all had a spiritual base and they were not mimicking anyone else. They had their own vision and understanding. So those are the people I would follow in my life. Particularly Cartier-Bresson because I was closer to him than I was anyone else.

Rachel : Who were your mentors as a young photographer?

Bruce : Well my mentors were not photographers. They were architects, poets, musicians…and bums. (laughs). I absorbed from anybody, all those people. There wasn’t any specific person.

Rachel : How were bums your mentors?

Bruce : Well when I say bums that could be someone who is not famous, that’s what I mean. It was just someone I was interested in. It might be this guy, Ed Bragg, who lived in Central Park all year round. He had a winter residence and a summer residence in the park. We got along pretty well and I said, “Ed, I’ll never photograph you unless I tell you I’m gonna do it.” And I said, tomorrow morning I’d like to photograph you when you’re still asleep, is that ok? “It’s ok.” And we got to know each other. He was a big guy, with big feet. They used to call him “Big Foot” in the park. And I gave him a thermos as a gift for his birthday. And he said, “I can’t accept it.” And I said, “Why?” “Because it would be stolen. I can’t hide a thermos in the park.” He took it anyway, but he taught me that that’s a different world. Living and surviving in a different world than I survive and live in. So I learned something from him.

Kickstarter Project – A Photographic Memory