Emaho: Can you tell us about your early life in Tehran and the moment you first realised that making images and objects could become your primary way of expressing yourself?

Niki: From as early as I can remember, sound, image, and language were inseparable from everyday life in our home. Music was always present, films opened up new worlds for me,

and books quietly shaped my imagination. Very early on, these elements became a natural language through which I related to the world. As a child, I spent a great deal of time at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanoon), which at that time was a truly special place for artistic education. Being immersed in that environment and attending its art classes left a deep impression on me. Without fully realizing it then, those experiences played a significant role in forming the foundations of who I would later become as an artist. Still, there is one particular moment that remains vividly etched in my memory. I was a teenager, having just begun my studies at art school, when I found myself in Sara Rahmanian’s studio. She was showing me a sketchbook she had recently completed, slowly turning its pages. In that moment, I experienced a profound and indescribable pleasure—one that came not merely from looking, but from sensing the possibility of making. It was then that I first understood that images and objects could become my most intimate and honest language for expressing and understanding the world.

Emaho: You studied sculpture at the Tehran University of Art. How did this academic training shape your artistic language and your understanding of form, space, and material?

Niki: Studying sculpture at the Tehran University of Art was less about mastering a specific medium and more about learning how to think through material. It was there that I began tounderstand material not simply as a tool for execution, but as something to be explored, touched, and listened to. The experience of bringing an object into being—working through resistance, limitation, and unpredictability—was deeply engaging and formative for me. This way of thinking continues to shape my practice, even when I work primarily with

drawing and painting. At the same time, my academic experience was not without its challenges. I believe that art education in Iran, particularly at the university level, is in need of meaningful change. Much of the academic environment feels rigid and repetitive, relying on established frameworks rather than fostering a truly inquisitive and dynamic space. Paradoxically, this sense of stagnation pushed me toward a more personal and self-directed path, encouraging me to develop my artistic language beyond formal structures and outside the confines of the

academy.

Emaho: Outside of formal education, how did your artistic journey unfold? Were there early works or moments that felt like a true beginning for you as an artist?

Niki: I remember preparing my first body of work for what would become my very first group exhibition at Delgosha Gallery, curated by Shabahang Tayyari. The initial body of work I

presented to him was met with an exceptionally harsh critique—so much so that, for a moment, I felt deeply discouraged and began to doubt both myself and my direction as an

artist. Yet at the same time, a certain inner stubbornness—perhaps an essential part of my character—prevented me from retreating. I returned to the work, reconsidered everything,

and developed a new body of pieces for that same exhibition. In the end, that series became a turning point for me. Even today, those works remain among my favourites, not only because of their outcome, but because they marked a moment of resilience, recalibration, and a more serious commitment to my artistic path.

Emaho: Your solo exhibition Noah’s Ark at Dastan’s Basement marked an important milestone. What was the core idea behind this project, and how did its characters and imagined world begin to take shape?

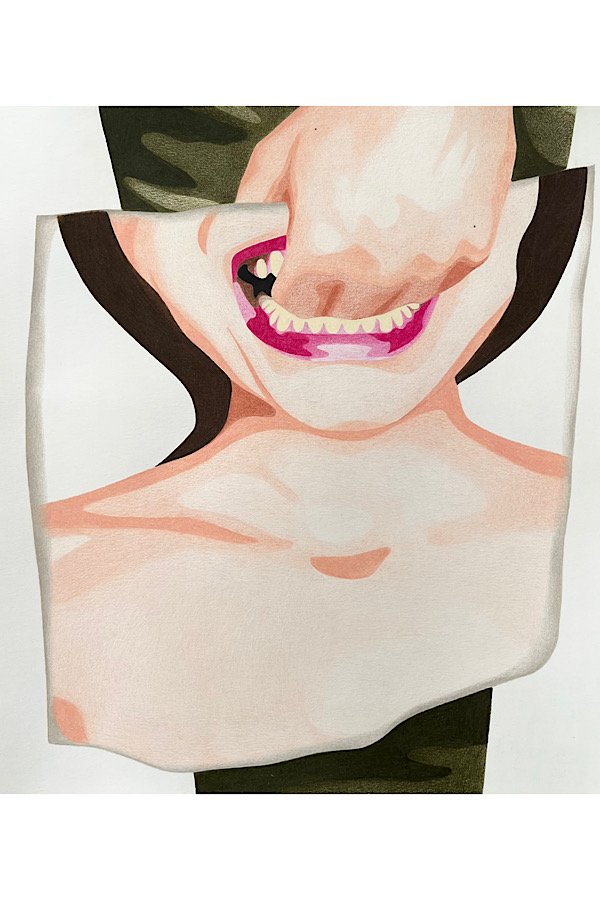

Niki: Noah’s Ark was developed during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, at a time when feelings of uncertainty, suspension, and vulnerability were deeply present in everyday life.Although the title may evoke a religious narrative, the project was never intended as a biblical reference. Instead, I approached the ark as a metaphorical shelter—a temporary refuge in the midst of instability, a space of pause rather than salvation. The imagined world of the project emerged gradually through drawing, repetition, and play. Rather than beginning with a fixed narrative, the characters slowly took shape as I worked, each one carrying its own presence and emotional charge. These figures are fragile, playful, and restless. Their sense of playfulness can be read as a response to the emotional numbness and stagnation that characterized that period—a small act of resistance against stillness and inertia. Through humour, exaggeration, and an almost childlike energy, the characters insist on movement and feeling, even within a precarious and uncertain world.

Emaho: In Noah’s Ark, you worked extensively with drawing and painting on cardboard, creating a narrative-driven universe. Why were these materials important to you, and what did they allow you to express conceptually and visually?

Niki: Working with drawing and painting on cardboard allowed me to engage directly with fragility—both materially and conceptually. Cardboard is an inherently vulnerable surface;it bends, absorbs, and deteriorates easily. It is never fully stable, and that instability became an essential part of the work rather than something to overcome. Using colored pencils on this surface is particularly demanding, as it leaves very little room for correction. In many cases, even a small mistake can compromise or completely destroy a piece, which creates a constant sense of risk and attentiveness throughout the process. This vulnerability closely reflects the emotional atmosphere of the world I was trying to construct. Despite these challenges, cardboard has remained one of my favourite materials to work with. It continues to function as an ongoing challenge—both technically and emotionally—keeping the act of making life alive, uncertain, and deeply engaging.

Emaho: You have also participated in group exhibitions such as Carbon at Etemad Gallery. How did that experience differ from presenting a solo show, and what did it mean to see your work in conversation with other artists?

Niki: Participating in group exhibitions has been a very different experience from presenting a solo show. In a solo exhibition, you are able to construct a complete and self-contained

world. In a group setting, however, the work must stand on its own, without the protection of a singular narrative or atmosphere shaped entirely by the artist. Seeing my work in conversation with that of other artists allows new meanings to emerge—sometimes ones I had not anticipated myself. Rather than feeling competitive, these situations feel dialogic; the works respond to one another, creating a shared space of exchange. For me, group exhibitions encourage attentiveness and reinforce the idea that my practice exists within a larger, evolving artistic landscape.

Emaho: Many of your works appear playful at first glance, yet carry an underlying sense of unease or ambiguity. What kinds of themes or questions are you most interested in exploring through this tension?

Niki: In my work—especially in more recent pieces—the first encounter often feels slightly awkward. There is a sense of hesitation or discomfort at the initial moment of looking, as if something is not entirely settled or familiar. I am interested in that fragile space before interpretation becomes clear. The playfulness that appears in the work functions as an invitation, both for the viewer and for myself. It offers a way in, a gesture that feels light or approachable, while allowing more uneasy and ambiguous emotions to surface beneath. Rather than resolving this tension, I try to sustain it—letting the work remain open, unresolved, and emotionally porous. Through this balance, I am less concerned with delivering answers than with creating a space for feeling, projection, and quiet introspection.

Emaho: As a young artist working in Iran today, what challenges do you encounter most frequently, and what continues to motivate you to sustain and develop your practice?

Niki: One of the ongoing challenges I face is the necessity, at times, to slightly soften or adjust certain aspects of my work—particularly its erotic charge—in order to be able to present it

publicly. This negotiation can be frustrating, especially when it creates a distance between the work as it first emerges and the work as it is ultimately shown. That said, I try not to let this limitation define or restrict my practice. Instead, it has pushed me to find more subtle, indirect ways of embedding desire, intimacy, and bodily sensation into the work. Rather than being overt, these elements become quieter and more ambiguous—woven into gestures, atmospheres, and relationships within the image.

Emaho: Looking ahead, how do you see your work evolving after Noah’s Ark? Are there new media, narratives, or exhibition formats you feel drawn to explore next?

Niki: At the moment, I am preparing for my next solo exhibition. Working with coloured pencils on cardboard continues to be at the centre of my practice, as it remains a material I feel

closely connected to. At the same time, I am beginning to think about introducing elements of volume into my future exhibitions. This feels like a natural step for me—an extension of my ongoing interest in material, fragility, and physical presence, rather than a shift away from what I am already doing.