England –

‘It began as a way of remembering the craftspeople and laborers of my adolescence,’ writes Ken Grant on the back of his latest book, No Pain Whatsoever. ‘My ever changing colleagues, who came and went like the work and who taught me, in beautiful and sometimes desperate ways, how to grow things in a difficult land.’

‘This book is about the quiet hours and days, relationships that ebb and flow, flourish or fail, and what we do – and, sometimes, about all we can do.’ No Pain Whatsoever starts with a picture of the docks. Liverpool used to be a seafaring town, but here the sky is grey and dank, the water still, unmoving. There are cranes, ships and frayed ropes but nothing much seems to be moving, nothing seems to happening. Flip the page and the movement comes. A man holds a child on the ferry across the River Mersey to Birkenhead. His face is lined, his eyes look down. In the background a girl stands looking out at the river, a man stands stuck in thought.

Image©Ken Grant

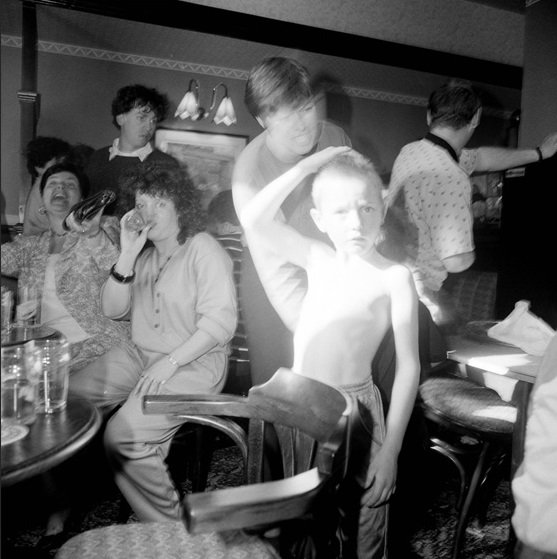

This is a book of faces then, faces that stand out against the worn out landscapes that Grant photographs in. They are faces that are hard, thoughtful, worn-out, inquisitive, that beckon you into their world. The man with the metal frame around his face, the young Fernando Torres lookalike with the broken arm, the women leaning against what might be a beachfront wall.

Everybody has a history in the book and the history ties in to the places Grant photographs; New Brighton, the ferry, the docks, the pubs but most of all the streets. Liverpool is a city that looks and feels like no other. It’s run down yet at the same time grandiose. It has an edge to it but also has warmth, wit and charm like no other. It’s a working class city that wears its identity with pride. The docks might be gentrified, the city centre surrounded by a circle of dereliction (still) but it’s still an amazing place to visit and see. And that ambivalence comes out in Grant’s pictures. He’s a gentle man with a soft voice. Listen to him speak and he lulls you with a lovely line of Grantisms; an elegant, poetic world that flows like a very gentle stream in exactly the direction Grant wants to take you. But No Pain Whatsoever is not really that gentle. He shows the faces of matriarchs that have a an inner core that has suffered, survived and come out stronger, we see shopping centres and red-brick terraces that are decorated with litter and a sense of neglect and decay. And then there is the dereliction, the empty lots, the scavenging and the search for a living; these pictures (very quietly) also tell a story, a story of a city marginalised by government, a city stigmatised for its own identity, a place where men gather bits of iron together to scrape a living, where a dump provides a way to survive. That is where the book is strongest and where it goes beyond a collection of work, where the people and the place come together, where people inhabit urban landscapes of empty streets and shattered car parks in an almost lyrical manner, as though the concrete were grass and the terraced housing glades of trees and babbling brooks.

Image©Ken Grant

For all its urban edge, No Pain Whatsoever is not a miserable book. It’s a book that’s full of spirit and life, where people are looking and searching and challenging. It’s a distillation of some of the recent greats of British photography; Tom Wood, Martin Parr and Chris Killip all spring to mind, but at the same time there is something different, something so intricately tied to the city of Liverpool that marks it out as quite original; it’s a love letter of a book, a love letter that bares the heart of the city, warts and all and proclaims Grant’s love for it, in good times and bad, for richer and for poorer, till death do them part.

Colin Pantall is a UK-based writer, photographer and Senior Lecturer at the University of South Wales, Newport.

Photography