India –

Emaho caught up with Mumbai-based photographer Aparna Jayakumar who has done some very interesting documentary, editorial and commercial work. She has done publicity stills for Bollywood films such as Kaminey, Gandhi of the Month and Saat Khoon Maaf. She also teaches media students at Sophia College.

What made you develop an interest in photography?

I got interested in photography when I was in college. My mother bought me my first 35 mm film SLR camera, the Nikon FM10, when I was 19. I enjoyed shooting on the streets, and making portraits of my friends. My family was always supportive of my interest in photography, although at first my mother did warn me about it being an “expensive hobby”!

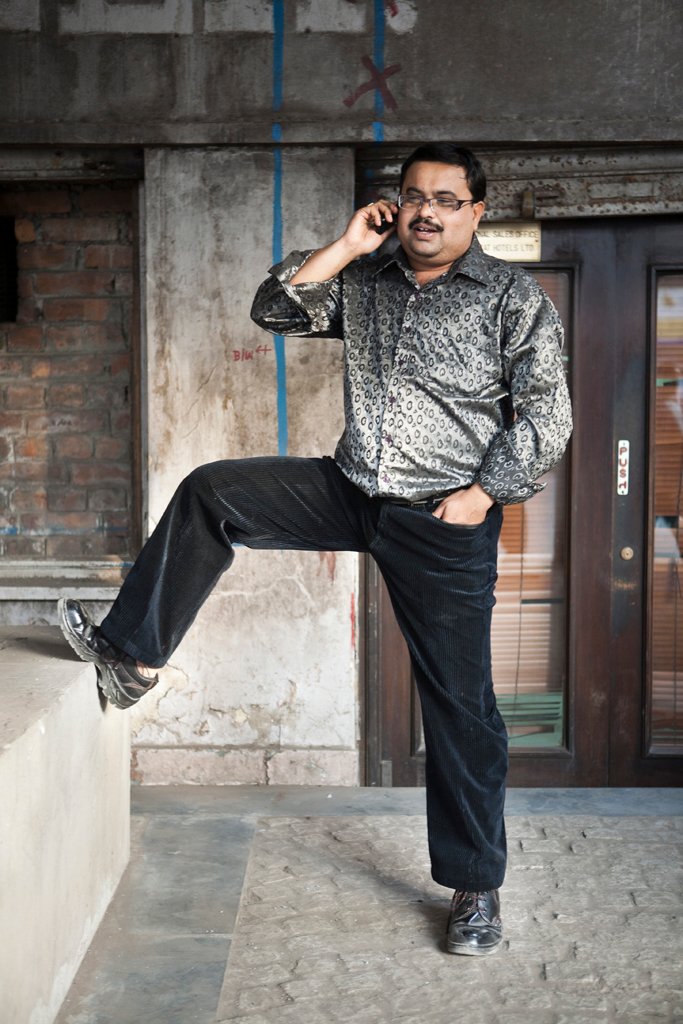

From the series “Flex, Feroze!”, images from the Parsi Bodybuilding Championship in Mumbai

What made you take up your project on Parsi bodybuilders?

I heard about the Parsi bodybuilding championship from a friend who had seen an advertisement for it in a Parsi newspaper. Growing up, I have always had a fondness for the Parsi community. I found the idea of a bodybuilding championship in the community immediately intriguing.

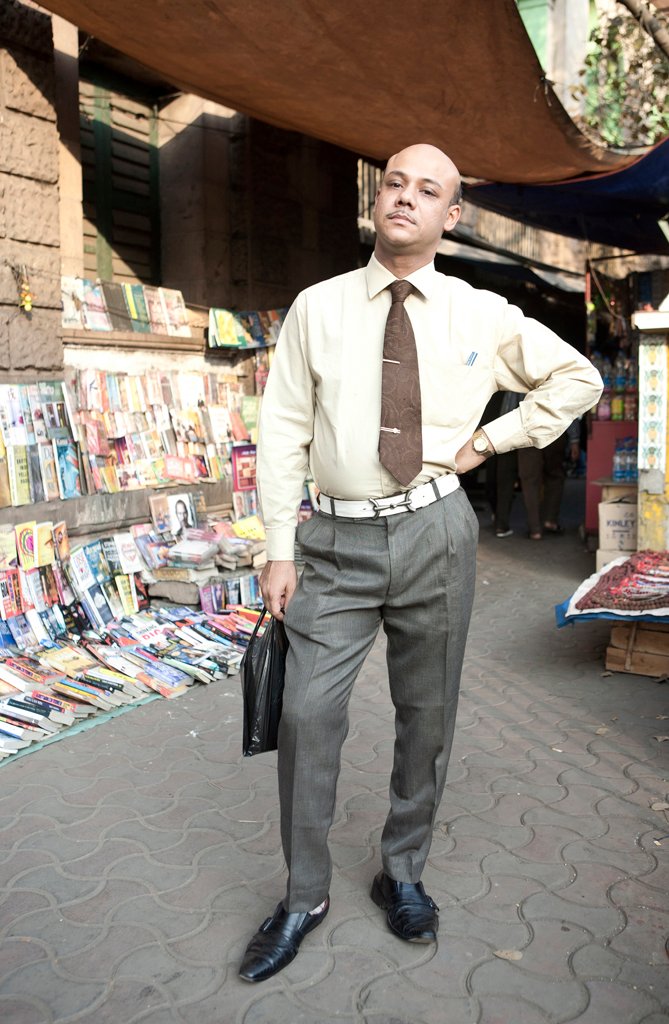

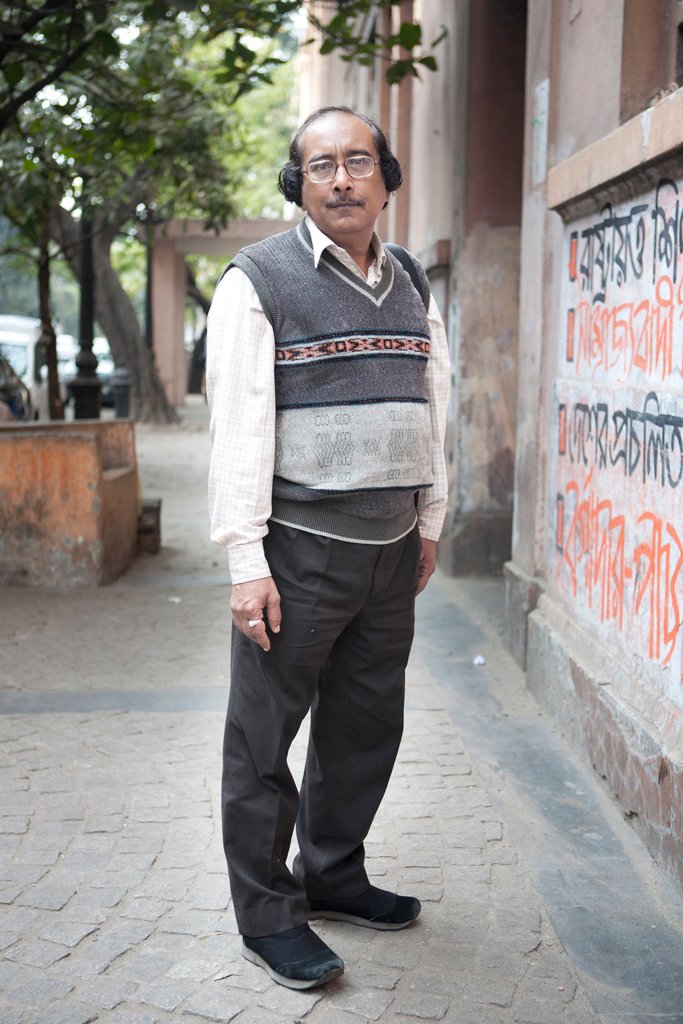

From the series “Flex, Feroze!”, images from the Parsi Bodybuilding Championship in Mumbai

What do you think the annual body building and weight lifting championship means to the Parsis as a minority community?

Not many people know this, but body building has been a popular sport among the Parsis. In the last few years though, there has been a decline because of the lack of participation and funds. It is a well-known fact that the Parsi community worldwide is dwindling. I was interested in creating ironic images of bodybuilders (the symbol of life-force) in a community on the decline.

From the series “Flex, Feroze!”, images from the Parsi Bodybuilding Championship in Mumbai

Your project Ek Pyaali Jannat takes Mirza Ghalib’s poetry and places it in modern day Mumbai. The ‘pyaali of jannat’, is equated with ‘chai’ that provides solace for a busy Mumbaikar. What does the use of stop motion signify in this project?

I chose to use the stop-motion style of photography for Ek Pyaali Jannat because the protagonist is a photographer; I thought this form would give the storytelling an edge. Also, I was curious to experiment with stop-motion and see what I’d get. Originally, the director Neha Kaul wanted the film to be a love story between a man and a woman, but one night she had an epiphany, and decided it would be far more interesting if the love poem were for a cup of chai. No points for guessing what she had been drinking that night.

Poster of the short film ‘Ek Pyaali Jannat’ (A Cup of Paradise) starring Deepak Dobriyal

Your story on the Premier Padmini and how it sustains the lives of so many people is intended for a book. Tell us a little about it.

I was commissioned by an Italian publishing company to work on a book of illustrative photographs of Padmini taxis in Mumbai. They were interested in the colour, the design and the kitschy art that adorns the taxis. I started out shooting the obvious, but as I spent more time with the subject, I realised that there was a larger, human story – about the city in transition, about the immigrant life, about old and new, about change. That’s how ‘Goodbye Padmini’ – the story of Mumbai’s disappearing taxis – evolved as a project.

Your work on women who step out of the domestic sphere and take up professions that are usually associated with men was showcased as part of the Inside/Out exhibition. What were these compositions like and what made you document them?

‘Inside/Out’ was a group show in which four photographers, including myself, explored gender and space in the urban context. It wasn’t particularly about women taking up traditionally “male” professions, although there were a couple of images that depicted that (an image of a female butcher in Athens). For me, it was about the different kinds of interactions I had observed between men and women in the public domain, and about looking at spaces that are inhabited only by women, such as the beauty parlour, or the ladies compartment on a local train.

From the series ‘Inside/out’

What do you feel working on the temporary constructed, yet so close to reality sets that movies use today?

Growing up in Bombay, cinema was my first love. I remember watching Pulp Fiction as a sixteen-year-old and wanting to be a filmmaker. Years later, when I was given the chance to work as a film publicity photographer, I was thrilled because it meant I would get to do two things I loved – taking photographs and learning about the film-making process by being on set. I enjoy watching a film being made – you see a whole world being painstakingly created, then recorded and eventually destroyed. The fine line between what is real and what is constructed inspired my ‘Nowhere Land’ photographs.

Harvey Keitel in a still from the unreleased film ‘Gandhi of the Month’

A lot of your work is rooted strongly to Mumbai. What makes it the city for your stories other than the fact that you reside there?

It definitely has to do with the fact that I live here. Bombay is a very difficult city to live in. A novelist friend of mine, Altaf Tyrewala, said, “Trying to survive in Bombay is a full-time job in itself”. I couldn’t agree more. Bombay is not very photogenic either; it is so congested and cluttered that it is hard to make sense of it when photographing it. Few contemporary street photographers have been able to do any remarkable work in Bombay. Most Bombay photography is ridden with clichés. I find that I need to leave Bombay at least once every couple of months, to keep my sanity. Yet there is a sense of freedom, honesty and a certain pulsating energy here that I haven’t found elsewhere, and Bombay continues to be my muse.

Shahid Kapoor in a still from the film ‘Kaminey’

You once commented that Bombay was yet to open up to looking at photography as an art. What does that mean? Is it just limited to the city of Bombay?

Last year, many new avenues for the study and discussion of photography opened up in Bombay – Open Show, Photocaddy, Bombay Photographers’ Club, The Last Lecture series, etc. Up until last year, photo events were few and far between. I am happy to see the change.

Priyanka Chopra in a still from ‘Saat Khoon Maaf’ directed by Vishal Bhardwaj

Do you think it is easier for a female photographer to address and document issues of gender with specific reference to Asian societies?

Women photographers have more access to other women; this makes it easier to take on subjects that are more intimate and private. Many parts of Asia are still rather conservative, and it is harder for male photographers to document the stories of women.

From the series ‘Goodbye Padmini’, the story of Mumbai’s disappearing Padmini taxis

Earlier in 2012 you had conducted a series of inspirational talks as a part of Viewfinder at Studio X in Mumbai along with four other photographers that are fast emerging in the Indian photography scenario. Who was your intended audience and how was the response to the talks?

Last year, I had connected with like-minded photographers in Bombay who wanted to create an environment in which photography can flourish as an art form. We wanted to create more awareness, have more talks and discussions, and conduct photography workshops that are accessible to all. We had a large turnout at the Viewfinder event, and the talks were well-received.

From the series ‘Goodbye Padmini’, the story of Mumbai’s disappearing Padmini taxis

What role do you think photography is capable of playing in political activism and social transformation?

I think the Bangladesh-Pathshala model is a great example of how photography can be used for social change. Pathshala, over the years, has created many fine photographers who are dedicated to documenting the state of their country and its social, political and environmental issues. The strength of their work has put Bangladesh on the world photography map, and has created tremendous awareness about these issues. At their photography festival Chobi Mela, they display the work in public spaces, on the streets, and make it accessible to the common man. I’d like to think of it as a photography revolution.

Tell us a little about your aim for The Photo Project workshop series that you had conducted in October 2012.

Being an independent documentary photographer can be a lonely experience, and one can hit roadblocks if one does not have a mentor. I have had this feeling myself several times. It was this need for mentorship that I wanted to address through the Photo Project workshop. Organised by Photocaddy, this workshop helped a group of photographers work through individual projects over a period of a month, with me as their mentor. The workshop was concluded last Saturday, and I am happy to say that some promising work has emerged from it.

From the series ‘Goodbye Padmini’, the story of Mumbai’s disappearing Padmini taxis

You were among the nine tutors for the 2012 Anjali Photo Workshops for kids that take place as part of the Angkor Photo Festival. What is the kind of work that you did as a tutor?

Teaching children is a truly rewarding experience; they are always brighter than you’d imagine, filled with wonderfully fresh ideas and boundless energy. I enjoyed teaching at the Anjali House Photo Workshops at the Angkor Photo Festival last year.

What would you say is the contribution you make to the fraternity of women photographers in Asia?

Art has sensitised me to the world around me. I have tried to get people interested in the study of photography as an art form. I teach young women at Sophia College and try to open up their minds through photography. I started the Bombay Photographers’ Club early last year, and have been organising a photo event every month. I’ve had people tell me that they have been inspired by my work. I am only a drop in the ocean, but I try to do what I can, genuinely, from the heart.

From the series ‘Goodbye Padmini’, the story of Mumbai’s disappearing Padmini taxis

What projects do you plan to take up in the near future?

I plan to continue work on my Goodbye Padmini and Babumoshai projects. I have some other collaborative projects in the pipeline. And one or two ideas of my own, but I am looking for the right language to tell those stories.

Interviewed by Marukh Budhraja

Photography by Aparna Jayakumar