Emaho: How did your early life between two cultures shape your sense of identity, memory, and eventually your way of seeing the world through a camera?

Tanya: My childhood unfolded between two sensibilities: the Austrian structure I inherited from my mother, which grounded me, and the Lebanese reality shaped by my father, which added layers of warmth, unpredictability, and intensity. Both formed essential parts of how I understand the world.

Moving between these worlds taught me that identity is rarely singular; it is layered, porous, shifting. In Beirut, memory isn’t a quiet archive; it lives in the brief ruptures that punctuate daily life. These dual foundations informed the way I look at the world, gradually teaching me to notice nuance, to sense what lies beneath the surface, and to recognise the fragility and endurance that often exist in close proximity in people and places. Photography eventually became the language through which these intertwined identities found clarity.

Emaho: When did photography first enter your life as something more than a hobby? Was there a specific moment, teacher, or visual experience that made you realise this could be your language?

Tanya: Photography entered my life long before I understood it as my medium. As a child, I held a camera almost instinctively, drawn to the act of framing what I couldn’t yet articulate. The shift from an intuitive practice to a vocation happened gradually, shaped by mentors who encouraged me to trust my sensibility and by encounters with images that revealed the emotional weight of looking with intention. There was no single turning point, but rather a slow accumulation of moments in which I realised the camera allowed me to approach the world with both distance and intimacy. It became a way of making sense of memory, dislocation, and desire.

Emaho: Beirut appears throughout your work as both muse and mirror. What was your first photographic relationship with the city, and how has it changed through years of conflict, reconstruction, and resilience?

Tanya: My first photographic relationship with Beirut was shaped by longing and an attempt to understand a city that held both my most formative memories and my earliest experiences of rupture. I photographed it to hold onto something, to slow down its volatility. Over the years, this relationship has matured. Beirut has become less a subject and more a companion. The city continues to shift, and so does my gaze. What remains constant is the emotional tether. Beirut mirrors my own transformations. I photograph it to stay connected to a place that shapes me daily.

Emaho: Your images often balance intimacy with quiet observation. How would you describe your approach behind the camera—what draws you to a scene, a person, or a fragment of everyday life?

Tanya: My approach is instinctive and quiet. I am drawn to scenes that hold emotional residue: a gesture, a pause, a threshold between public and private. I rarely chase dramatic moments; instead, I gravitate toward what feels fragile or overlooked. I think of photography as a form of listening. The world communicates through small, often unspoken cues – moments that register slowly and ask for attention rather than explanation. When something stirs a faint recognition in me, I follow it. My images form across different kinds of moments, often when something quietly asks to be observed rather than defined.

Emaho: Some of your most recognised photographs capture Beirut’s emotional contradictions: beauty, fragility, loss, and longing existing side by side. Which early images or series do you feel became turning points in your visual identity?

Tanya: Certain early photographs taught me who I was becoming as an image-maker. Some were made in moments of stillness, while others were captured during periods of uncertainty in the city. These images revealed to me that my visual identity leaned toward subtle contradictions: beauty that contains an ache, landscapes that hold their wounds with dignity, people who carry tenderness alongside heaviness. These early works helped me recognise that my gaze was not only observational but deeply emotional, shaped by memory as much as by place.

Emaho: You’ve worked extensively in a city shaped by war, instability, and shifting political realities. What do you see as the role—or perhaps the responsibility of photography in a place marked by conflict and rupture?

Tanya: Working in a city shaped by rupture means the camera cannot be neutral. Photography becomes a form of witnessing, but also a way of preserving what might otherwise disappear – spaces, gestures, states of mind. I don’t see photography’s responsibility only as documenting conflict directly.

Instead, I believe its power lies in holding space for the emotional landscapes that conflict creates: the persistence, the quiet griefs, the brief joys that survive despite instability. Images can counter erasure, they can insist that ordinary life, with all its fragility, deserves to be remembered.

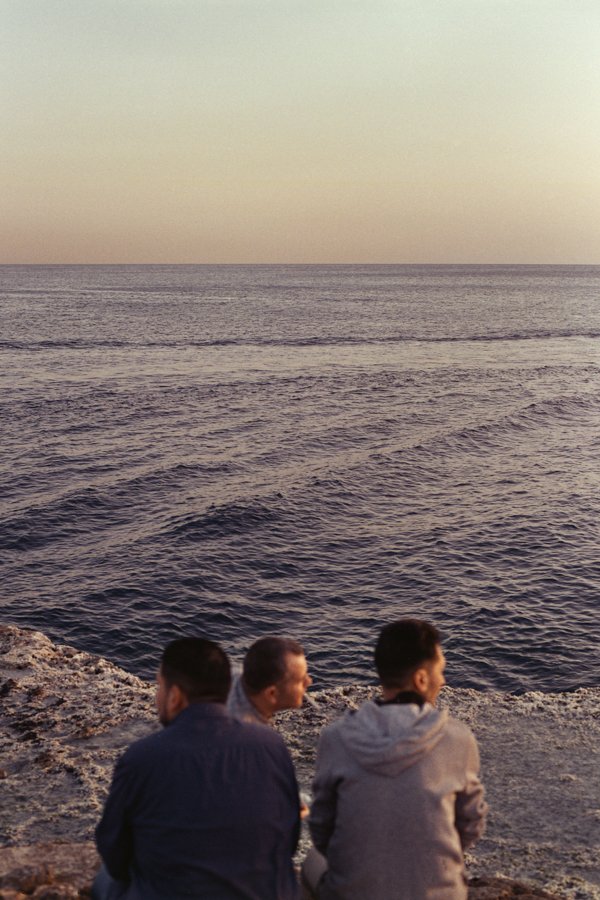

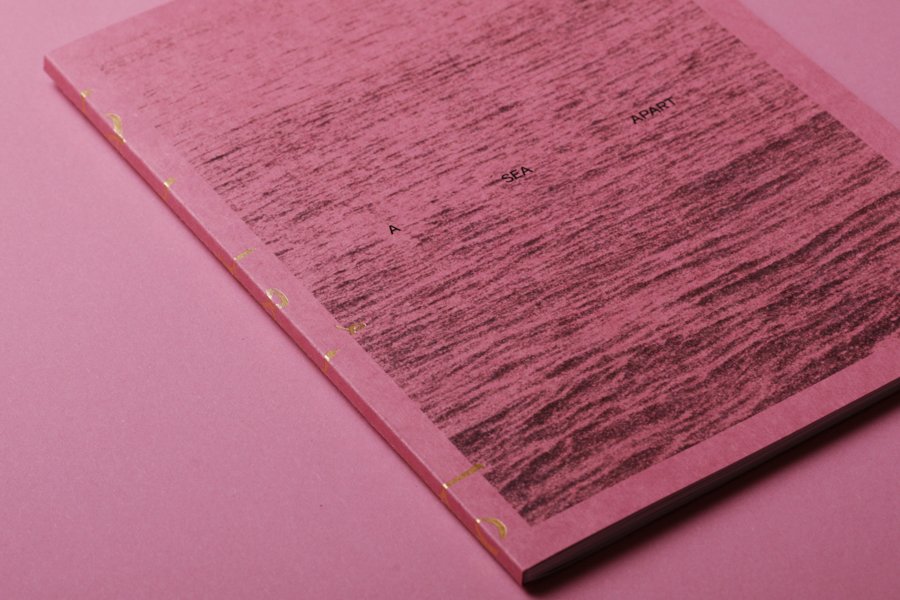

Emaho: Your photobook A Sea Apart reflects on diaspora, distance, and the intimate tension of being connected to a place you are not fully in. What was the emotional starting point for this book, and what did you hope it would capture?

Tanya: The emotional starting point for A Sea Apart lies in an earlier period of displacement during my childhood, when longing was shaped by physical distance from the place where I feel most myself. The book became a way to reflect on how separation – in my case shaped by the Lebanese Civil War – produces a particular kind of longing, and how images can sustain a sense of closeness even when one is far away. The title speaks to the sea that once lay between me and Beirut, marking both a literal and emotional distance. Through the book, I hoped to explore how photography holds memory in place, allowing attachment to endure across absence and time.

Emaho: Many of your projects explore themes of belonging and displacement. Do these themes come from personal experience, or do they emerge from the communities and environments you photograph?

Tanya: These themes are part of my personal history, but they also emerge from the environments I photograph. I grew up between cultures, and that duality inevitably shaped my sense of belonging. But Beirut itself, its constant transformation, amplifies these questions. When I photograph, I’m not only looking outward. I’m tracing the contours of my own relationship to place, and the ways communities negotiate their presence amid uncertainty. The themes are both lived and observed, personal and collective.

Emaho: What do you love most about Beirut—its people, its texture, its light—and how do these elements continue to inspire your work, even when you are photographing elsewhere?

Tanya: The sea is a defining presence for me in Beirut. Recently, I’ve been drawn to photographing Beirut from the sea, from a boat, where the city comes into view from a calm distance.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what new projects or ideas are you currently exploring? Is there a particular narrative, city, or emotional landscape you feel compelled to document next?

Tanya: I am continuing Beirut, Recurring Dream, expanding it into new forms as a way to explore the city’s shifting archive and my own evolving relationship to it. I’m increasingly drawn to narratives that ask how memory endures – within families, within cities, and in those spaces that open between presence and return. I hope to publish another book that brings together new photographs and texts, and the idea of making a film has been circling me for some time, though it remains in its early, exploratory stages.