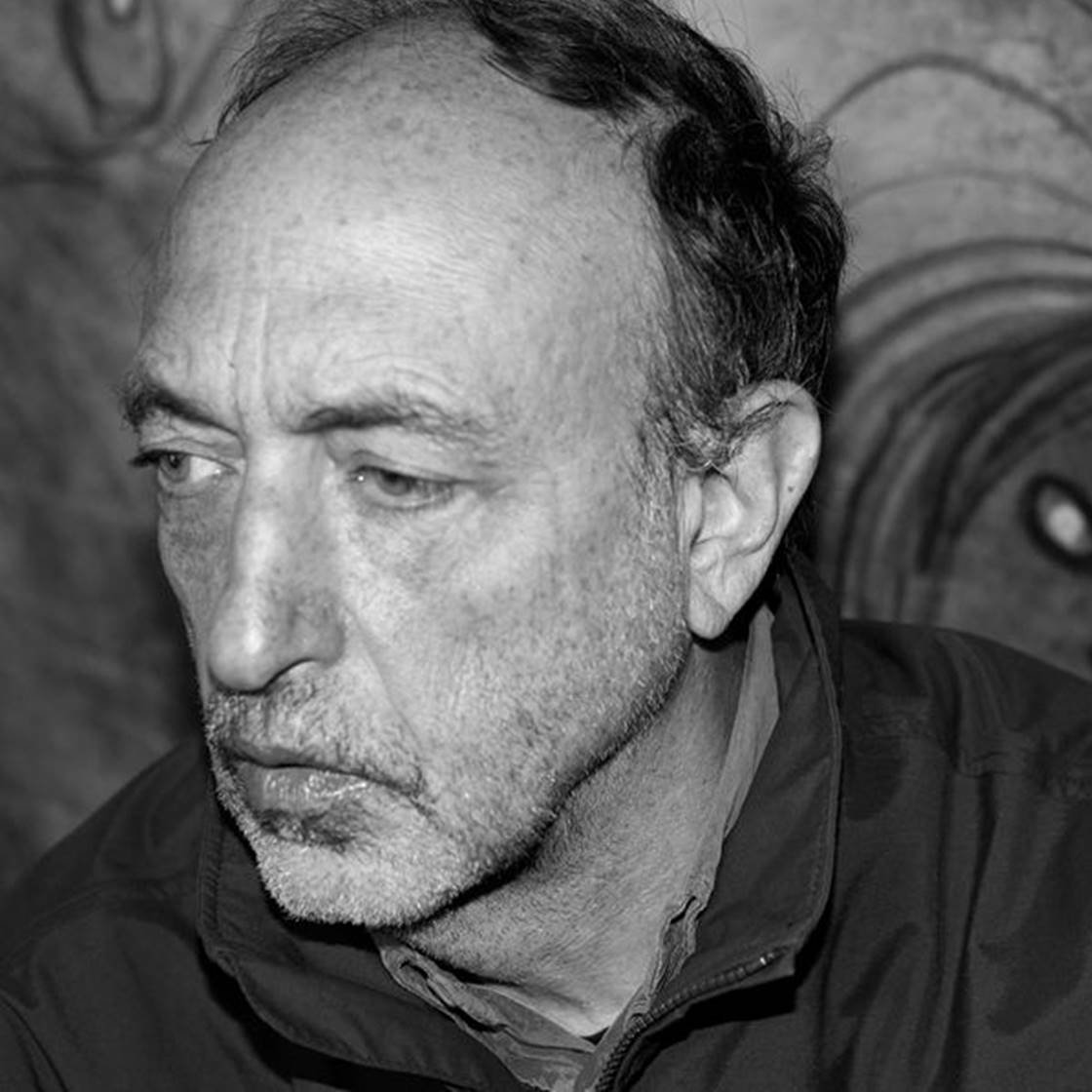

Emaho: You grew up between France, Belgium, and the United States. How did this multilingual, multi-country upbringing shape your sense of place and your curiosity about borders and identities?

Mathias: It’s a good question – I believe it gave me a sense of curiosity for the others. I don’t really have a sense of a unique place, that sense is multiple. It has open my vision and understanding towards other culture and identities from an early age. Plus I’ve grown up in different social standards living at times in under privileged neighbourhoods vs more privileged once. I’ve registered in over 10 different schools from my first grade to my final year of high school in three different countries. Not quite the definition of a stable up bringing. It definitely helped me have this sense of over-adaptation to all these situations I’ve encountered.

Emaho: What first drew you to photography, and how did your studies in communication and journalism in Brussels lead you toward documentary photography rather than written reporting?

Mathias: My uncle was a fashion photographer in Paris and I would run into him every now and then throughout the years. He would usually come back from exotic destination and show me his work and I think unconsciously I admired his lifestyle and work at the time. Later on I got myself into social communication and journalism throughout my studies which definitely shaped my desire to draw myself in documentary. My education was literate but cinema and photography always had a deep influence over me which led me to photography rather than written reporting.

Emaho: You briefly worked as a photographer for the Belgian national daily Le Soir before becoming independent. What motivated your shift from newsroom assignments to long-term, self-directed documentary work?

Mathias: Freedom. I first started as an intern at Le Soir through my studies and then briefly worked for the national Belgian newspaper. I very much enjoyed my experience at Le Soir and yet believed in this notion of slow journalism and wanted to conduct my own stories in my own terms. I left Le Soir to move to Bangkok in 2006 and started working as a freelance photojournalist.

Emaho: Much of your practice engages with social, political, and environmental realities in regions such as Turkey, Iraq, and their surrounding borderlands. What responsibilities do you feel as a photographer working in politically and culturally sensitive territories?

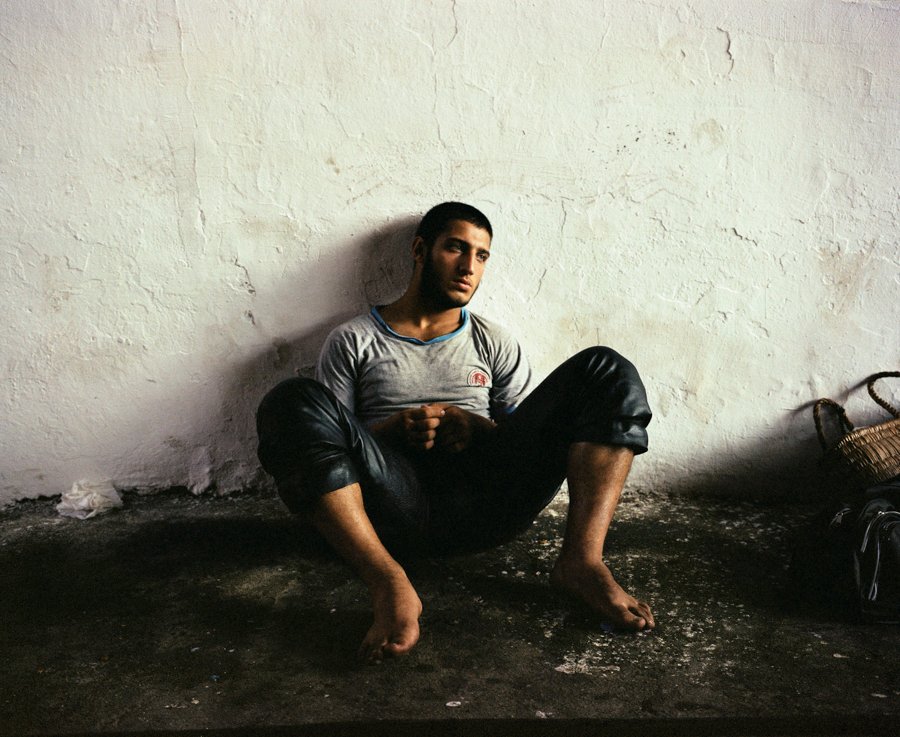

Mathias: The only responsibilities I feel I truly have is to stay true to the events and realities I witness – The notion of identity and territory are very relevant in sensitive regions I’ve worked on throughout my career – I worked with various minorities surrounding the Turkish and Iraqi borders for instance while living in Turkey. I was always driven into giving a voice to the forgotten whether I was in Laos with the Hmong’s or in Turkey with the Kurds or even in China while photographing the Uighurs in Xinjiang.

Emaho: Your long-term project Transanatolia explores contemporary Turkey and its border regions. How did this project begin, and what did years of travel and immersion there teach you about power, identity, and transformation?

Mathias: Transanatolia began over this quote of Recep Tayip Erdogan: “We are asked why we are interested in Iraq and Syria, Ukraine, Georgia and Crimea, Azerbaijan and Karabakh, the Balkans and North Africa. But these countries are no strangers to us. From Hatay to Morocco, you will find the traces of our ancestors. (…) For us, it is not about other worlds, but pieces of our soul.” To probe the complexity of Turkish identity, one must project beyond its borders. Turkey radiates, spreads its ‘soft power’ from the Balkans to Central Asia, from the Black Sea to the Red Sea. Its influence extends into all the former Ottoman territories and to the borders of China, in Central Asia, distant homeland of the Turkish people. With Transanatolia I wanted to explore all these territories which Erdogan call ‘the borders of the heart’. The fragmentation of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War remains a trauma and the Turkish leader imposes an authoritarian, paternalistic and police state to reconquer the lost territories. The method is often brutal as we’ve witness over the last decade. Transanatolia aims to witness the Turkish identity past its present and past borders.

Emaho: Another significant body of work follows the Tigris and Euphrates river basins, examining the human and environmental consequences of water depletion, dam construction, and climate pressure. What compelled you to focus on these rivers, and what stories did you feel were urgently missing from public discourse?

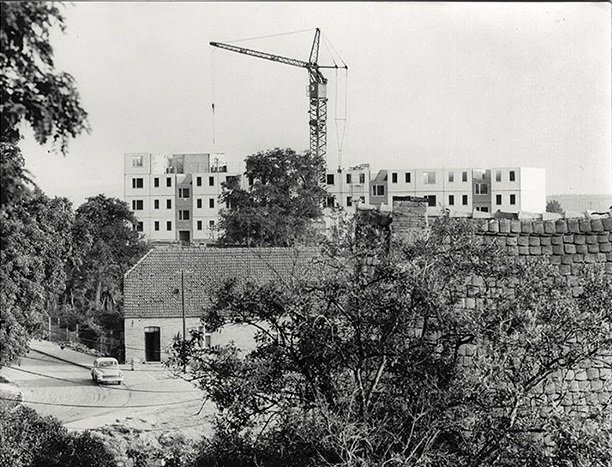

Mathias: The domestication of water by Ankara and how it has affected 20 million people along the banks of these two mystical rivers is what initially drove my attention to focus on this project. The basin of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Southern Turkey, which feeds Syria and Iraq, is rapidly drying up. Turkey’s controversial Guneydogu Anadolu Projesi — or Southeastern Anatolia Project. GAP, as it is known, is currently Ankara’s most significant territory planning project, involving eight provinces, irrigate some 1.7 million hectares of earth from 22 different dams all fed by water from the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers. Along with the environmental and social risks, the geopolitical impact of the dams cannot be ignored either. The development of the Ilisu dam for instance (latest dam construction in the region built on the Tigris River) has been severely criticized by neighboring Iraq and Syria, who accuse Turkey of appropriating waters of two rivers that connect to their territories, which are already hit by arid conditions and drought. The history of these rivers and their presence in our own cultural history may be one of the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in the world, spanning some, 10,000 years of world heritage. Mesopotamia is a unique historical region where a mix of Assyrians, Roman and Ottoman monuments belong. Some of these significant historic and archaeological sites is today at risk of being demolished forever due to the GAP project. Beyond this idea of a war on waters in the region I also wanted to focus my attention at the time of the Kurdish population of southern Turkey where the two rivers occupy a pivotal place in the daily life, ecology, and history of millions of people in Syria, Iraq and Turkey.

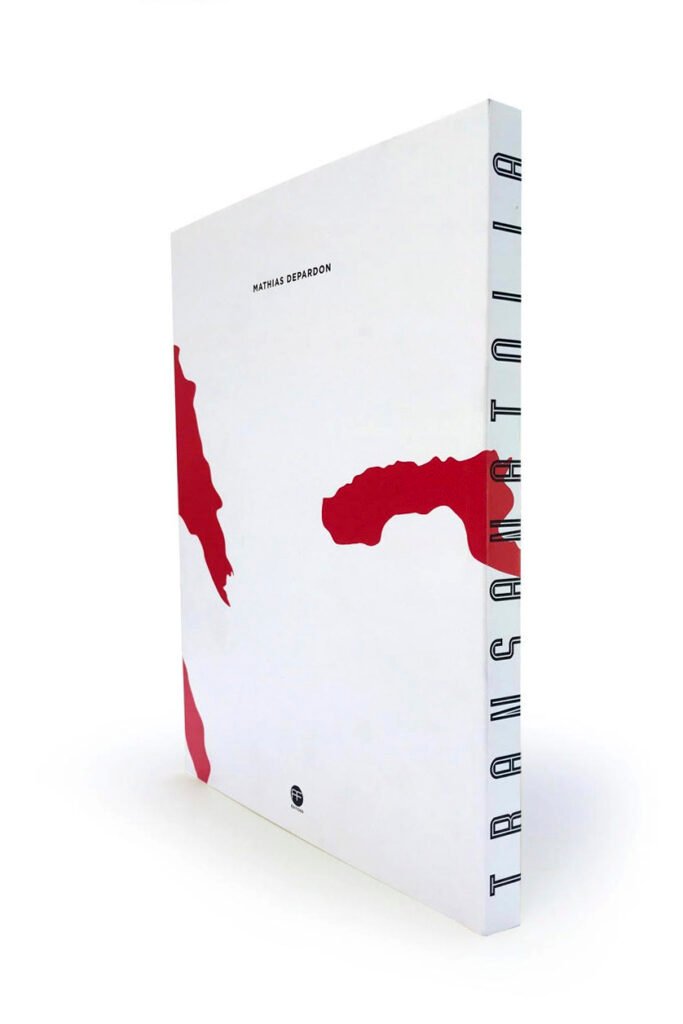

Emaho: You have published photobooks, including Transanatolia. How do you approach translating a long-term photographic project into book form, and what does the book medium allow you to express that exhibitions or online platforms cannot?

Mathias: Books allow you to shape your narrative in a more constructive way. I believe it is truly the way to come to term with a project. Generally it’s how a project will be remembered along with an exhibition perhaps.

Emaho: Your work has been exhibited internationally, from major European photography festivals to institutional spaces. Which exhibitions or presentations have felt most pivotal in shaping your career, and why?

Mathias: Undoubtedly my first exhibition of Transanatolia in France at the National Archive Museum in Paris in 2017. It was an amazing opportunity to exhibit in such a space. It’s hard to define how such event can be pivotal for your career. It was for a recognition of my work – did it truly changed my career, maybe.

Emaho: In 2020, you received the Yves Rocher Foundation Photo Award in support of your ongoing work. How did this recognition and grant influence the development, scope, or visibility of your projects?

Mathias: The Yves Rocher Foundation helped me financed a trip to Iraq to keep on documenting the Mesopotamian Rivers and add a second chapter to my project called Tales from the Land in Between mostly shot in Southern Iraq.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what new territories, themes, or visual approaches are you most interested in exploring, and how do you see your photographic practice evolving in the coming years?

Mathias: I’ve been working on a project around sand and sand extraction since the past five years now. Sand is the most consume resource on earth after fresh water. We don’t think much about sand except perhaps when we’re at the beach. You hear people talk about the end of oil and water but sand is an underestimated natural resource which is at threat of disappearing with massive consequences on the environment. In 2014, the United Nation Environmental Program published a report titled ‘Sand Rarer than One Thinks ‘which concluded that sand mining greatly exceeds natural renewal rates and that the amount being mined is increasing exponentially mainly as a result of rapid economic growth in certain region of the world.

So far I’ve worked in over 8 different countries to document sand mining and its direct consequences on the environmental but also how it has impacted farmers and fishermen’s.