Emaho: Growing up in Irbid, what parts of your childhood—your neighbourhood, the landscapes, the people—first opened the door to drawing and painting for you?

Maram: I began drawing before I was even fully aware of the world around me. I started at a very young age, and perhaps this passion is something innate within me. Over time, the city, the neighbourhood, the home, the people, and the surrounding nature all became enduring sources of inspiration.

Emaho: You are often associated with impressionist landscapes and quiet scenes of daily life. What did those early works give you, and how did they help you understand the artist you were becoming?

Maram: In fact, I did not begin with Impressionism. My early stages were defined by experimentation – I worked freely with different tools, styles, and visual imaginations without attaching myself to any specific school.

My inclination toward Impressionism came later, as a natural evolution. Through close observation of artworks from around the world and sustained visual nourishment drawn from the history of fine art, I found myself gravitating toward it without conscious intention. I began by capturing the natural scenes around me – fields, houses, still life, moments of everyday life – and gradually, almost involuntarily, I fell deeply in love with this school.

Later still, again without deliberate choice, I noticed my work leaning toward Post-Impressionism. This kind of progression has occurred for many artists throughout history. Perhaps it is simply a natural outcome when one practices sincerely and belongs to a visual language with genuine passion.

Emaho: Your portraits of Gaza’s martyrs have struck a global nerve. Was there a specific moment or experience that compelled you to begin this emotionally and politically charged series?

Emaho: Yes. When the war began, I was deeply conscious, first, of being Palestinian, and second, of my belief in the full reality and justice of this cause. I carried a constant sense of responsibility toward what was unfolding in Gaza—the injustice inflicted on its people and its city.

I was also in an especially sensitive moment of my life. I had just become a mother to my second child, who was not yet a month old when the war began. At first, I consciously refused to draw what was happening. Somewhere inside me, there was fear—fear of fully accepting that the war might last a long time. Each day, I held onto quiet wishes, telling myself it would end the next day.

Everything changed after the Al-Maamadani Hospital massacre, when Israeli occupation forces bombed the hospital—an act that is forbidden, rare, and profoundly aberrant. Something inside me shattered. I realised that anyone capable of such an act had no intention of ending the war quickly, and that the violence would escalate without red lines.

At that moment, a conviction formed within me: anyone who possesses a platform or a means to speak, yet chooses not to bear witness to lives being crushed and taken without accountability, becomes complicit in the crime. I immediately recognised my role, or at least part of it. My first work about the war on Gaza emerged from that realisation.

Emaho: When you paint someone whose story carries immense pain and injustice, how do you navigate that responsibility while preserving their dignity and humanity?

Maram: This is the role of the artist—and the many questions that circle in the artist’s mind when striving to create work in an honest and responsible way. When injustice silences the oppressed, it becomes the duty of free people to become the voice that oppression tries to erase.

For the artist, and here I speak for myself, this requires a conscious ethical stance. One must never approach such work commercially—neither as an idea, a process, nor a product. It is enough to be a true voice for those silenced by injustice, and to treat the artwork itself with dignity, grounded in respect for the cause we are witnessing.

Emaho: Emotion sits at the centre of your work. Can you describe your process, from the moment a story reaches you to the moment a portrait feels complete?

Maram: Every story, every name among more than one hundred thousand martyrs, deserves to be honoured and remembered. In my mind, thousands of stories unfold. During the war, these lives occupied an enormous space in my soul and consciousness. I dreamt of them at night throughout the conflict.

The moment I decide to paint a particular work is not fully conscious. There is no deliberate selection process. Every life deserves to be painted, to be remembered, and perhaps to serve as a reason to prevent future bloodshed. I do not fully understand how I internally choose which story to document. At some point, the artist’s eye signals that the work is complete. At that stage, the artist becomes attentive even to the smallest aesthetic details, even in the most painful works. It is a harsh paradox, yet part of the nature of art. This tension is what gives art its psychological power.

Art is beauty – but true beauty lies in standing with truth and freedom. Perhaps it is this alignment that gives art its meaning.

Emaho: As a Palestinian-Jordanian artist working so intimately with Palestinian narratives, how do questions of identity, distance, and belonging shape your approach?

Maram: When I identify myself sometimes as a Jordanian artist and at other times as Palestinian, there is no internal conflict. I am a Palestinian-Jordanian artist. I live at the heart of the issues that surround me, foremost among them the Palestinian cause. It is impossible to separate a person from their environment. These realities are everything I know and everything that moves within my consciousness. They are intertwined far more deeply than words can fully express.

Emaho: Artists in the Middle East often face political pressure, censorship, and platform restrictions. What obstacles have you encountered while sharing this work?

Maram: I have not personally faced direct restrictions, except those imposed by Meta, which has relentlessly aligned itself with Zionist oppression. More broadly, artists addressing political issues in the Middle East frequently encounter censorship and pressure.

However, what has happened in Gaza has lifted the veil on the Western world, its institutions, and its media. Censorship and suppression are not limited to this region. While Middle Eastern governments often resist artistic expression that challenges political narratives, there remains broad recognition – aside from a few exceptions – of the legitimacy of the Palestinian cause.

Emaho: Your work has reached audiences far beyond the region. How has this global response shaped your sense of responsibility as an artist?

Maram: My commitment to what happened in Gaza is stronger than any attempt to reshape myself to meet audience expectations. The only real change is an increased sense of responsibility. When you feel that the voice you believe in resonates, you continue to speak.

Emaho: This series represents an intense and urgent chapter in your practice. As you look ahead, how do you imagine your work evolving, and what stories do you feel called to paint next?

Maram: This chapter has been both urgent and transformative. Looking forward, I carry these experiences with me. The stories of injustice, resistance, and human dignity will continue to guide my work – wherever they unfold, and however they demand to be told.

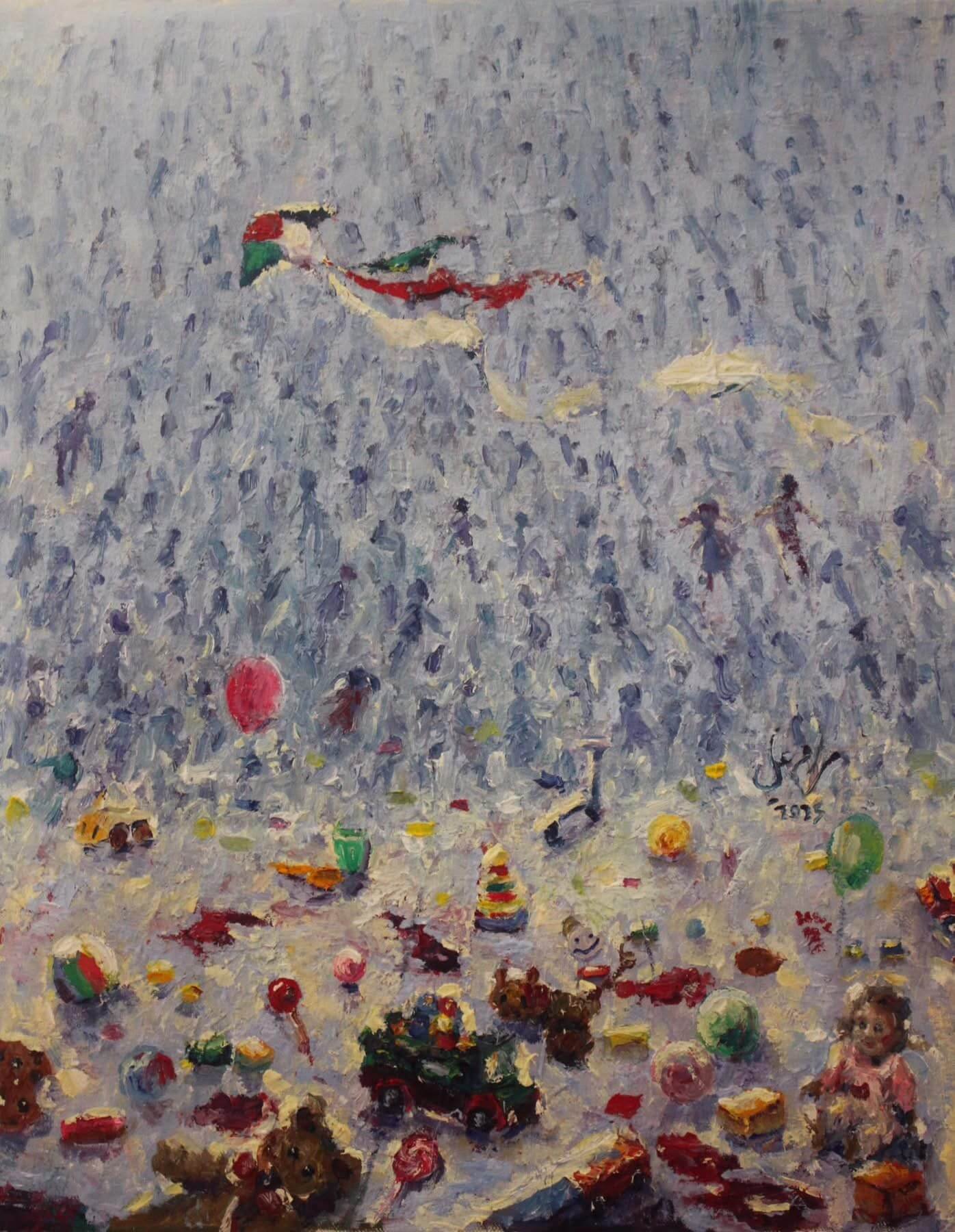

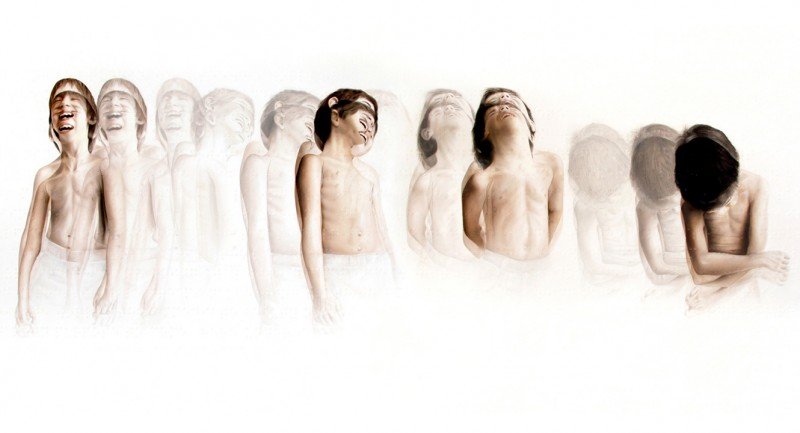

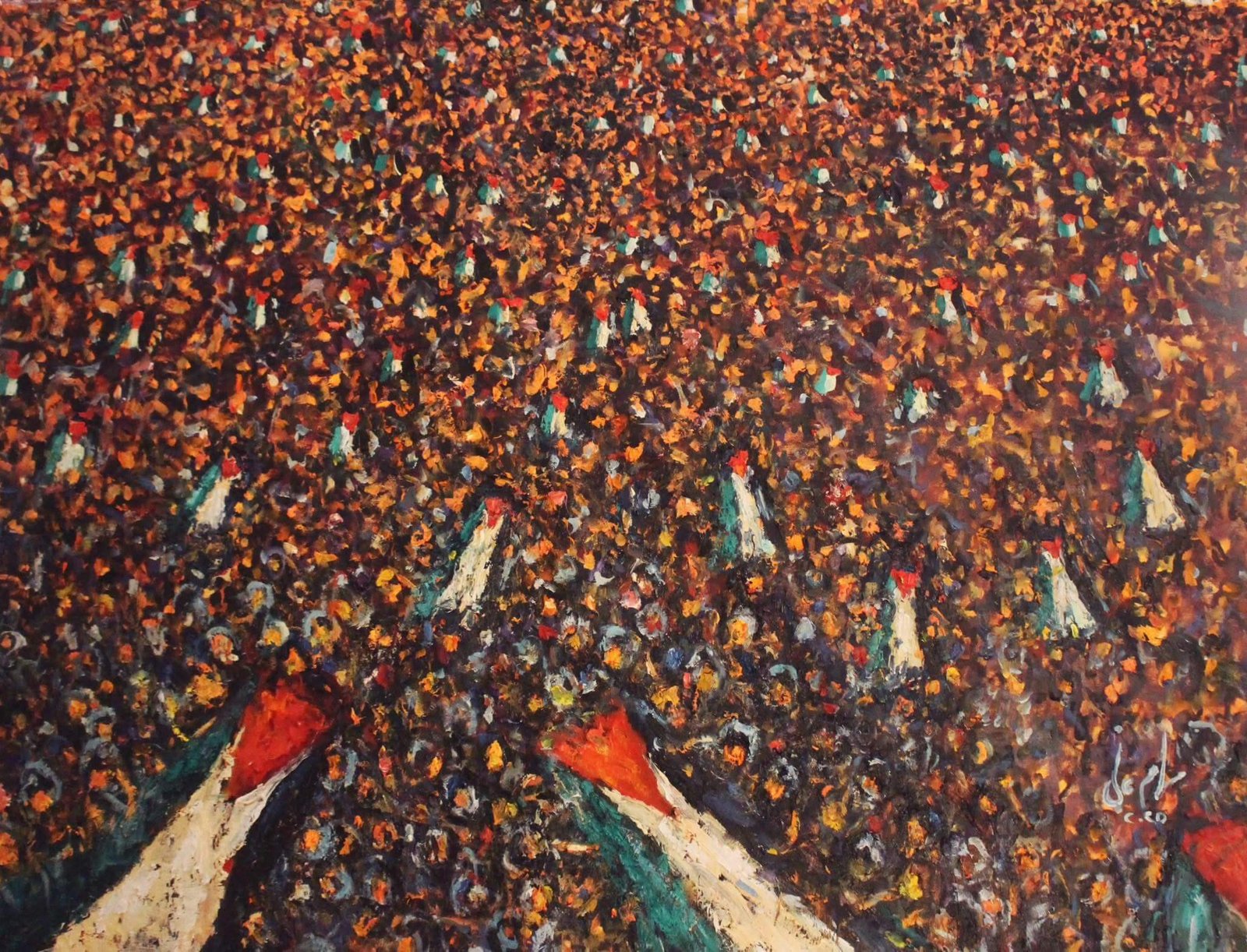

Art Work by: Maram Ali