Emaho: Can you tell us about your early life in the Netherlands, and the moment you first understood that making images and objects wasn’t just something you did—but a language you could speak to the world with?

Helmut: I grew up in a small city. I had a great childhood and fit in with my friends as the odd one out. Most of them found me “weird,” in a good way. I was never exposed to art growing up, neither at school, nor by my parents or friends. I had never set foot in a museum until I was 23, the age when I started art school. As a kid I was always making things, but I had no idea that this could be a way of living.

I did well in school and got good grades, until puberty hit. Suddenly, I didn’t care about school anymore and dropped out at 17. I started working at a printing company where my father was the financial director, with the expectation that I would eventually follow in his footsteps. I worked there for five years.

The first years were enjoyable; I started in the desktop publishing department and learned how to work with computers. The company made labels for all kinds of products, mostly ones you find in supermarkets. In the last year and a half, I moved into an office job, taking orders and talking to clients, I hated it. I would go to work on Monday wishing it was Friday. Looking back, those years turned out to be very important, because they taught me what I didn’t want in life.

I had been thinking about art school, so I visited a few open days. The moment I stepped into the art school in Den Bosch, I knew I belonged there. I applied, and got in. The next four years were amazing: I met my wife, created art every day, and fully immersed myself in the creative world. After graduating, we moved to Rotterdam, a more vibrant city with far more opportunities in the arts.

The most important lesson I learned in art school came in my second year. One of our teachers gave us an assignment, and she participated as well, which I thought was really cool. We each had to make an artwork for another person, and at the end, we presented our pieces to the group. When I saw my teacher’s work, I didn’t think it was very good. Up until that moment, I had thought art was something I didn’t understand, reserved for a select group of people that did understand. Seeing that my respected teacher had created something less than impressive made me realize she didn’t have all the answers either. Probably no one did. That insight was liberating. From that moment, I felt free to create whatever I wanted.

To me, art is about freedom, and it should be accessible to everyone. I find it a shame that it often carries an intellectual aura. Of course, some forms of art require knowledge of history, but art can also be accessible and communicative. People rarely say they don’t like music, but many do say that about contemporary art. I would like to see that change.

Emaho: Your pieces often land like visual one-liners—deceptively simple at first glance, then quietly revealing a deeper truth about everyday life. How would you describe your artistic purpose in your own words?

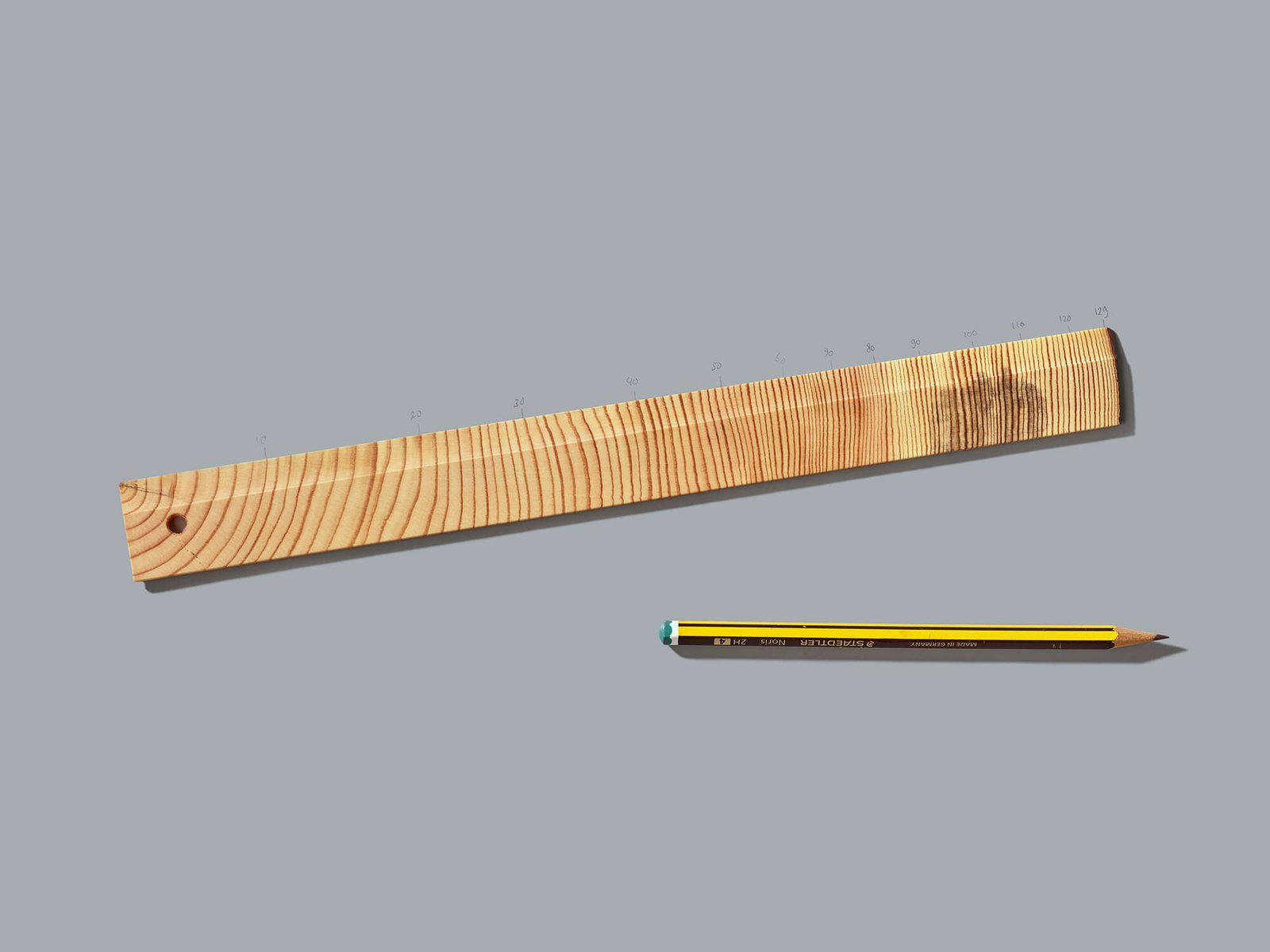

Helmut: Everything I do starts with an idea. I come up with a concept and then search for the medium that fits best. I like to keep things as simple as possible and want my work to communicate. I believe that every object, thought, or situation carries the potential for one or more good artworks. The challenge of uncovering these ideas is something I truly enjoy. I like when things are logical, yet seen from an unexpected perspective. To show the poetry in things we thought we already knew.

I also love improvisation, seeing how people solve problems they encounter in everyday life. People are naturally creative; when stranded on a deserted island or imprisoned, we invent all sorts of clever solutions. In our Western society, this kind of thinking is often discouraged, I would say, sabotaged.

Emaho: Can you walk us through one or two landmark projects that feel central to your artistic DNA? What made these works defining moments in the evolution of your thinking or process?

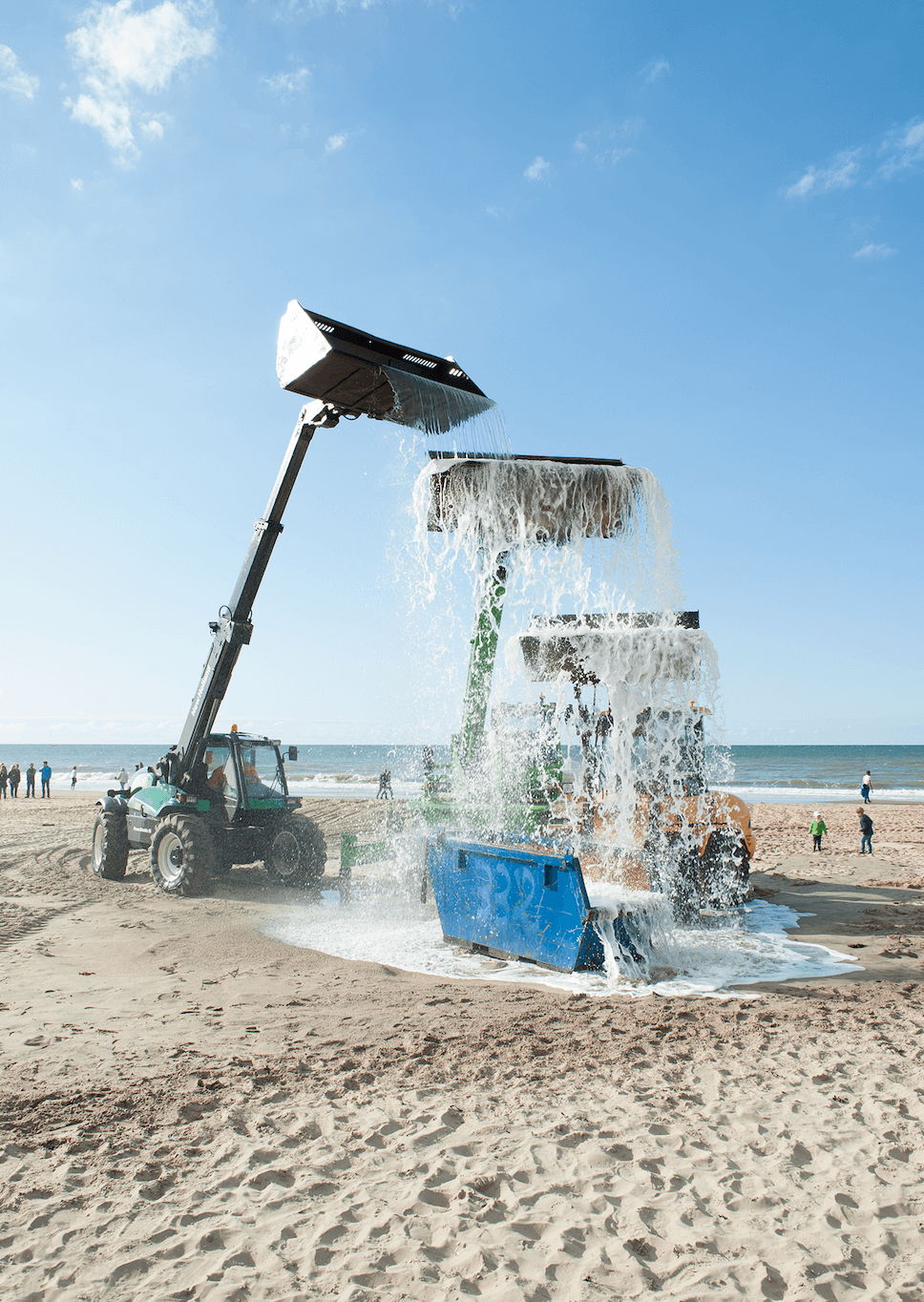

Helmut: In 2010, I created an artwork titled The Real Thing, an installation that transforms Coca-Cola back into clean drinking water. The idea came to me when I tried to look at Coca-Cola as if I had never seen it before, with the fresh, curious eyes of a child. What I saw was a dirty brown liquid, almost like wastewater. Reflecting on this, I realized that it would be logical to clean it, just as we do with our wastewater, filtering it back into pure, drinkable water.

The installation is a simple distillation setup. To communicate the concept clearly, I chose to boil the Coca-Cola in its own glass bottle. The liquid runs through the distillation apparatus, and the resulting clean water is displayed alongside the original drink. In this way, the process, and the idea, is made visually immediate for viewers.

The title The Real Thing references an old Coca-Cola slogan from the 1970s, which claimed the soft drink was “the real thing.” But of course water is “the real thing”. It’s the source of all life on Earth.

The installation also raises pressing questions about consumption and global inequity. Approximately three liters of clean drinking water are required to produce one liter of Coca-Cola. Meanwhile, in many parts of the world, people do not have access to safe drinking water, yet Coca-Cola is widely available. By reversing the manufacturing process and distilling Coke to recover pure water, the artwork invites reflection on how mindless consumerism affects the world we live in.

Another more recent artwork is Marking the Day. This piece features a large-scale date, inspired by the small date stamps often found in the corners of old photographs. It was created by blocking sunlight with road plates, which prevented photosynthesis and temporarily turned the grass yellow. The date, 6 October 2021, marked the opening of Ostrava’s Cuckoo Festival.

I like that we captured the artwork in a single photograph while using minimal resources: the road plates are reused, and the grass will naturally recover in the weeks after.

Emaho: A lot of your work plays with consumer culture, digital behaviour, and the absurdity of modern life—often with humour, sometimes with critique. How do you recognise which everyday phenomena are worth elevating into art?

Helmut: As Michelangelo once said, the sculpture already exists within the marble; his task was merely to chisel away the excess. I think the same is true for almost everything in life, though of course, some things are more generous than others.

Emaho: When people encounter your photographic objects — with their mix of concept, humour, and material presence — what kinds of reactions or interpretations do you notice most? Do these responses ever shift how you think about your next projects?

Helmut: Most of the time I’m not there to see the reactions of the public as I don’t make a lot of physical shows and my work for a large part exists online, but what I get from people is that they enjoy the humor, wit and playfulness in my work.

I believe you should always make artworks that you want to make and not take the opinion of the public into account while creating an artwork. When you put your love, energy and talent into a project, it will naturally resonates with others.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what new territories—conceptual, material, or cultural—are you most interested in exploring through your objects and installations in the coming years?

Helmut: As I’ve mentioned, I like keeping things simple and using as few resources as possible. Everything is already there, you just have to see it. My practice has been evolving in a way that I physically create less and less; sometimes, perhaps, just the idea is enough.

In the past, I published two books that are essentially sketchbooks, collections of written ideas accompanied by small drawings for context. I love that as readers move through these books, the artworks are created in their minds. For some ideas, I feel it’s unnecessary to make them physically, though for others it might be. When I explain an idea to someone, it takes shape in their mind, and I find that incredibly satisfying, I like the thought that this could be enough.

I don’t aspire to become a writer, so I will continue making physical work also. But in a world defined by overconsumption and constant pressure, I like that art can function in this way, existing in thought as much as in matter.

All the photographs by Helmut Smits