Netherlands –

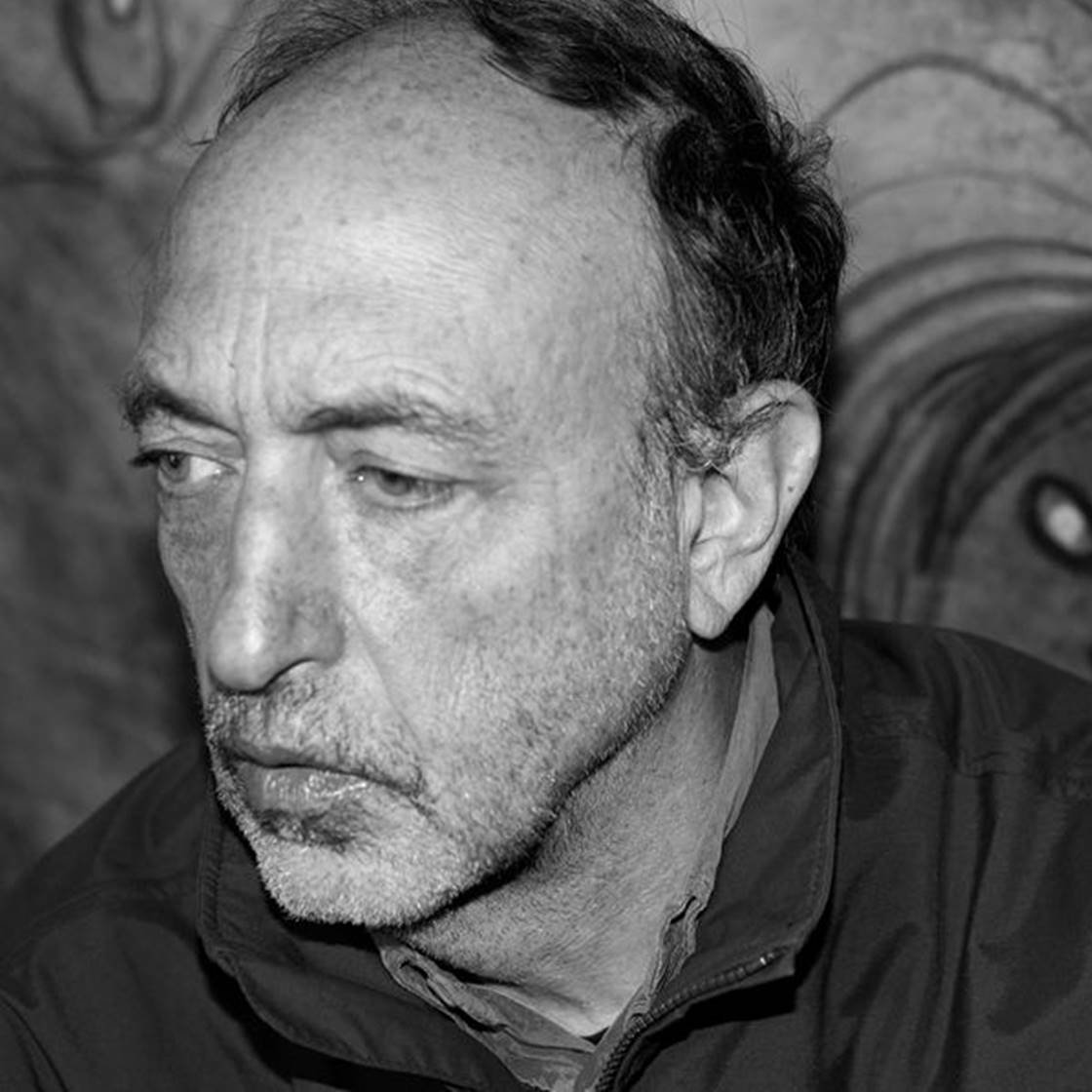

Hans Gremmen is a talented designer based in Amsterdam known for his innovative work with photo books. Regularly sought out by photographers, Gremmen is known to be quite an authority on photobooks, having worked on several photobooks, including ‘Cette Montagne C’est Moi’, ’Sequester’, and ‘Libero’.

Emaho caught up with Hans in November, 2014 to have a conversation about his passion for the medium and everything regarding the photobook tradition and the contemporary photobook scene.

Manik: What inspired you to become a designer of photobooks?

Hans: It was not an obvious choice. It happened by chance. After graduating, I worked for architects and made text-based books. One day, a friend asked if I would like to participate in a collective project, involving10 photographers. They needed a graphic designer because they wanted to make a magazine, so they approached me. I liked the offer as I had been working a lot with type. As a designer, you always depend on the offers that people bring you. Even though I liked what I was doing, I thought it would be nice to do something different. So, together we made this small magazine. What happened next was important as Jaap Scheeren and Anouk Kruithof, who were publishers, saw the magazine, and liked it very much. They asked me to design their book ‘The Black Hole’. It features experimental printing. It combines full colour and black over it so you can see only half of the pictures. Eventually that book got a lot of publicity, as well as a couple of awards. After that, I received many more such offers. I was really interested in photography in relation to books, as I think books are a great medium to showcase photography. That is how I got involved in photobooks. It just happened, but I embraced it.

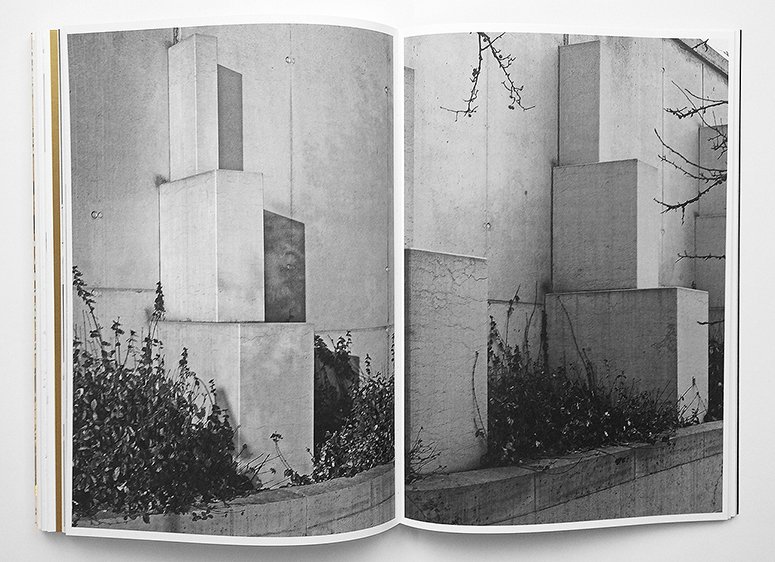

‘The Black Hole’

‘The Black Hole’

Manik: In which year did this happen?

Hans: This would be in 2004-5.

Manik: So it is almost a decade back.

Hans: I think it was 2005. Yes, it is almost a decade back. I should celebrate!

Manik: What do you find so engaging about the medium of the photobook?

Hans: I think photography is a medium that needs printing. You can print a photograph and put it on a wall; you can print the photo in a book, and it will be just as good. Unlike painting, where you have the original painting, and you have a reproduction, with photography, a photograph printed in a book is also the original. That photograph in a book is not better or inferior or superior to one mounted on the wall. That is what I really like – that you can have a printing press, which you can consider the equivalent of a darkroom, where you can create images. I try to push the borders of reproduction. So I use experimental ways of printing. This never for the sake of experiment, but always reacting to the content. It is inspiring for me to push the borders of the photobook as a medium as well as photography.

Manik: That is quite interesting! Your style of working with photobooks is unique as regards to the work you are dealing with. Do you feel you still belong to a certain school of design or design aesthetic? What can you tell us about your whole design process?

Hans: In the Netherlands, there is a rich tradition of collaborations with graphic designers and photographers that goes back to the 20’s, 30’s and 40’s. In the 80’s and 90’s there was a revival of this tradition there. I am in an atmosphere where people are very aware of experimental design, which gives me a lot of freedom. If I walk on the street, I encounter people like Willem Sandberg, a designer and one of the most important directors of the Stedelijk Museum in the past, who made beautiful typographical artworks on the walls of the subway system. This is something that has been integrated everywhere. So it is hard to say what has influenced me more or less. I had teachers who have heavily inspired me. Jaap Van Triest and Karl Martens also had an impact on me. They work in the field of architecture. Nevertheless, they pushed the boundaries of printing method. They were editors and graphic designers. This is something I grew up with; it is for me, a normal state of being.

Manik: Would you say it is the Dutch photobook or the rich history of printing that has got you involved in the medium?

Hans: I think it is the rich history, which is also implemented in Art School already. For instance, people studying photography are taught that their work can exist in photobooks. While studying, they seek collaborations with graphic designers. Designers do that as well because they need contacts. So it is these two groups: designers and photographers or artists or architects, that naturally find each other while studying, which is very fruitful. Every year as graduation gets closer, students approach me and ask if I would design their photobook. Although the content is often inspiring, and the people are very nice, I always try to encourage them to find people within the same art school. As I think that if you both are on the same level, then you can inspire each other. Graphic designers also need these opportunities and in this way the tradition is continued.

Manik: Could you tell us about the rich history of Dutch photobook design?

Hans: In the 1940’s there was an interesting group of photographers working, Carel Blazer, Eva Besnyö, Cas Oorthuys, Emmy Andriesse. One of my biggest heroes in terms of graphic design Dick Elffers was married to Emmy Andriessen. They published great works together. Dick Elffers had an assistant Jurriaan Schrofer (also married to a photographer), who later made fantastic books with Ed van der Elsken. The way Schrofer and Elffers deal with photography shows there is a close collaboration. They were very experimental and were involved in the edit, the way of printing, etc. Now that I think about it: From Schrofer there can be a direct line to Karel Martens: he was his teacher in Arnhem. And Karel was my teacher years later, so —although it feels strange to place me in this direct line— these roots are a fact, and —yes— also I am married to a photographer (laughs).

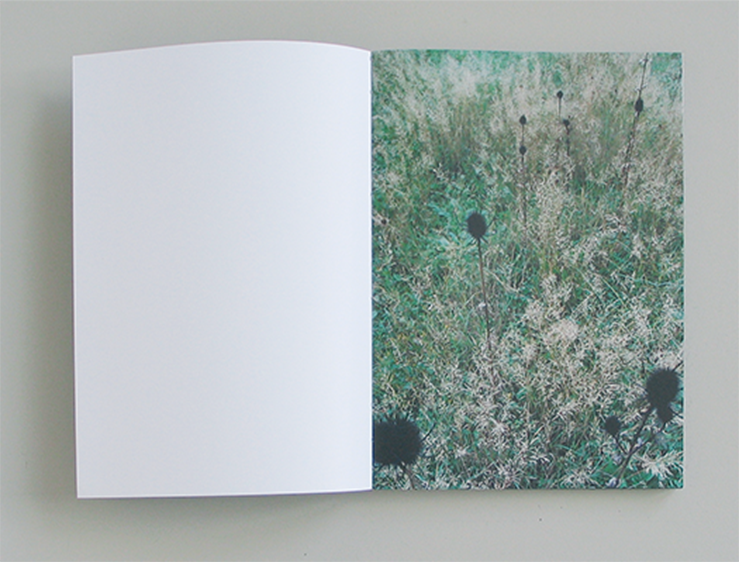

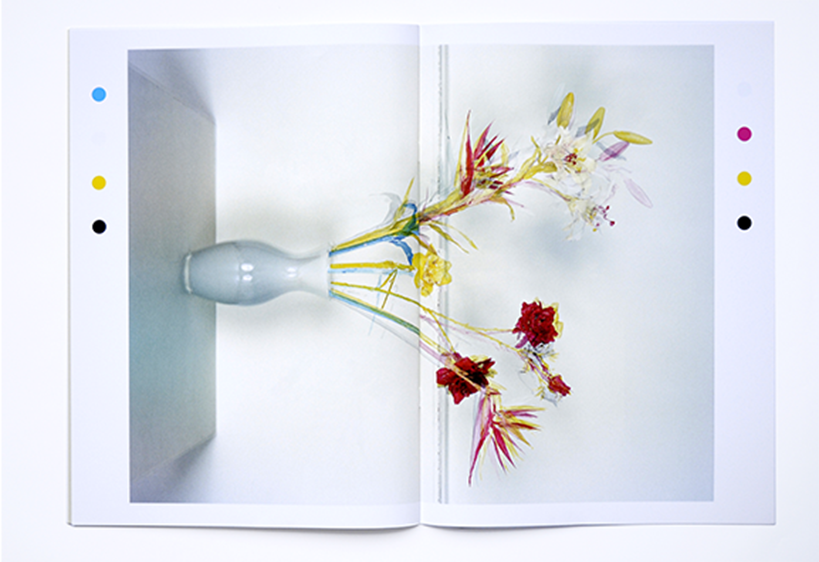

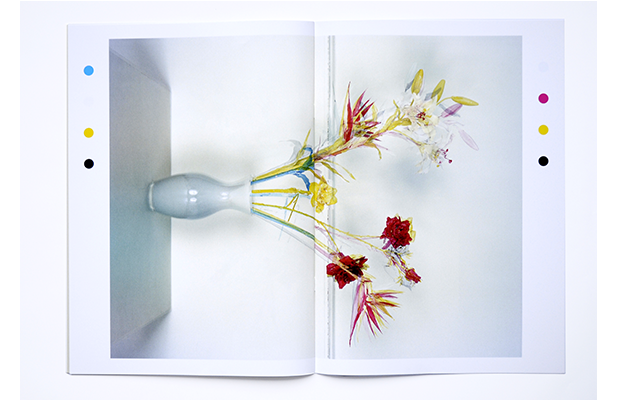

‘Fake Flowers in Full Colour’

Manik: What is the process of brainstorming that takes place when you start working on a new book with a photographer? For example, your work ‘Fake Flowers in Full color’ (Jaap Scheren), which came about from a conversation with the photographer on printing techniques.

Hans: ‘Fake Flowers in Full Color’ is exceptional because of the whole collaboration with Jaap. We constantly visit and talk to each other about both our works. He sits behind my computer and comments on the things I work on – not just his books but things in general. It happens the other way around as well. He asked me once how colour separations work in printing full colour; how the computer calculates the amount of magenta, cyan and so on, in an image. I opened an image of his, which had flowers, went to the channels in Photoshop, and showed him all the different colour layers. He liked the separate layers, for example, seeing only a magenta layer of the image. He thought it was beautiful, so we came up with the idea of making a manual colour separation that would be reconstructed while printing. Eventually, we printed the book that has four colours full colour of each other, so 16 colours in total. Usually when people talk to me about work, it is, very often, in progress. They ask me to participate in the editing process, and give me the material. I like not knowing too much about the project, so I can just dive into the material. You don’t have the photographer standing next to you explaining what you should see. I try to get the story out of the images. Then I ask questions, and then we start building. Initially, I try to get to the core of what the work is actually about; and then start adding layers making it more complex. The first and most essential thing is to get to the core, which I like doing alone. After that, there is intense collaboration on the editing and designing processes. We do it together as then I feel a lot of freedom to make perhaps, strange cropings or strange printings. When doing it with the photographer, I can decide more easily to ‘misuse’ so to speak (laughs); and I wouldn’t do it without permission as it is their work.

Manik: Do you think that a personal connection is important for you to work with a photographer?

Hans: Yes. During the process of putting the books together, we go through these, let’s say, emotional stages. At first, you are enthusiastic, later there is always this moment of fight, which happens as a result of having to make choices. It is always very intense, and it works better with some people more than with others. For me, there have been times where I have given a lot of energy and it just disappeared into a black hole. I cannot give all my energy if nothing comes back. So definitely, ‘personal’ doesn’t mean you have to be friends, it is a professional thing as well. But it works best if the energy comes equally from both sides.

Manik: Have you ever had experiences where you worked on beautiful projects that you could not complete because of the lack of co-operation?

Hans: Yes, I have. I have learnt over the years to trust the gut feeling that I get whether a project is going to work or not. There were times I thought that the projects were interesting, but then there was a gap. Maybe it was not a book that I should design. People also need to find the correct type of designer. For instance, in Cologne there was SYB who is a very different designer than I am but we work with many of the same people. I have noticed that the people who talk to me, also talk to him, as they try to find out who is more suitable. That is a good thing to do, because whom you work with, is an important choice. I have had a few experiences where I had thought, ‘Okay, if you want this kind of book maybe you should talk to this or that designer’. At times, you may think that a project is interesting but after a few months, it’s a dead end. Again, it’s the gut feeling that I had had from the beginning. For a good project, you have to make a good team with the photographer.

Manik: You have worked with various mediums including installations, cinema and print. How do you decide which medium suits the work best, and how much of that decision is made by the artist?

Hans: When you are working you find that out. For example, I worked with Karianne Bueno, for quite a few months or even a year, on her book about Vancouver Islands that revolves around a person there. Last week, I went to her exhibition at The Hague, where her books were on display and there was a radio playing in the exhibition hall. We were invited to dinner, where there was a random slide show of her work playing in the background. During different courses, she read a letter that she wrote, to this person on Vancouver Islands, Doug. I was looking at the images that were passing by and heard her voice, and I thought that maybe it shouldn’t be a book at all, maybe it should be a movie with the voice playing. I’m not saying that we will do that; probably we will make a book anyway. Such things you cannot predict, they just happen. When you work very intensely with somebody, then you can make suggestions, like to Karianne that we could make it a movie instead of a book; and sometimes it is indeed a good choice to do so.

‘Vancouver Islands©Karianne Bueno’

‘Vancouver Islands©Karianne Bueno’

Manik: Would you say that having a rigid decision or idea of what he or she is looking for, is not necessarily the best way to be, for an artist or a photographer?

Hans: It should always be an open dialogue, from my side, and from the photographer’s side. If a photographer says, ‘I want a hardcover book, 80 pages with glossy paper and bleeding images’; I would ask what would I have to do in that case. I take the photographer’s point of view seriously, as it comes from something, and I try to find out from where this desire arises. People have these desires, for example, that it needs to be a monumental book. I try to translate this typical approach into the abstract by asking why they want it that way. Sometimes the answer is very banal – that it needs to be a big body of work and it needs to be for a book. That is a starting point but I think of alternatives and a common meeting point.

They need to be very open to dialogue. Similarly if I would say, ‘Oh I have only made soft cover books for the past half year, and I want to make a hard cover book’ that is not the reason to do something. You have to be open and reactive to the content. There are many ways to come to a design, and if someone wants things a certain way I try to find out why. It is always open for discussion.

Manik: One of your quotes is, “As a designer I believe it’s my role to question the project”. What according to you is a good photobook or a good photobook project?

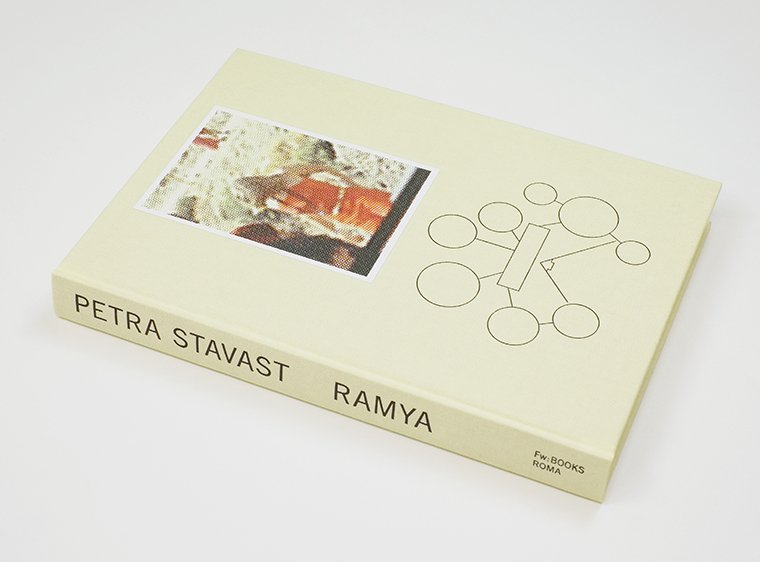

Hans: That is hard to answer because it is not one fixed thing. For instance, the book I showed in Cologne, Ramya, which I also sent you, did you get it?

Manik: It is one of my favourite books, by the way, just letting you know, from 2014!

Hans: I liked the fact that when that project came to me, it was open, and was in multimedia. It had many layers but there was one story, which was also not fixed or clear. There were a lot of layers and existential questions, but then I think the book as a medium can be used to peel off layers, to start building again, and to construct an all-new autonomy. It is like a new world with its own rules. The design is quite straightforward, but it is about editing and how to place the size of the images; everything has to reason, to open up the story. In this case, it should be a moving story and something that gets onto your skin. You have to understand the reader, and I say reader instead of viewer because this book is more like a reading book for me, which takes effort and time to consume. It is also like Fake Flowers or collaborations with Stephan Keppel. I think that with these kinds of books there is a lot of work and many details, which are not so obvious. It is like a hidden gem, and that is what I like to work on. It feels like there is a necessity to tell the story, and I am helping with that.

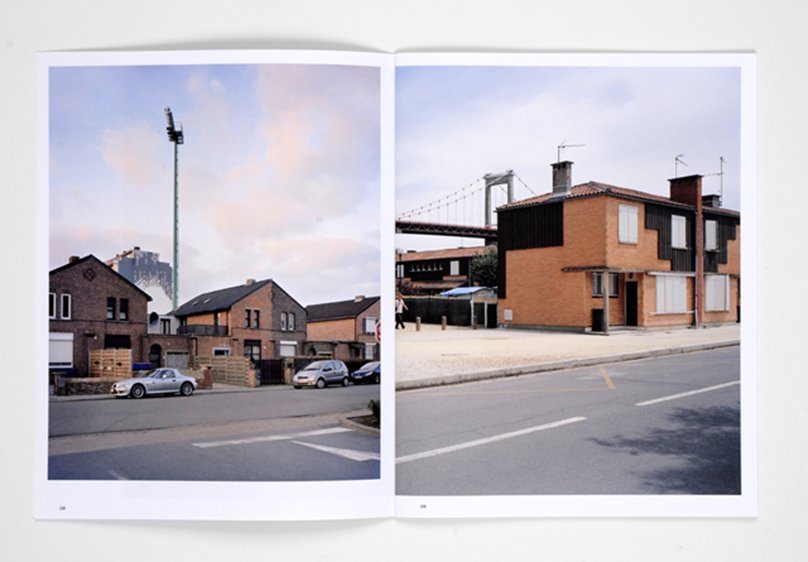

‘Entre Entree©Stephan Keppel’

‘Entre Entree©Stephan Keppel’

Manik: Then according to you, there is no set description of a good photobook or a good photobook design?

Hans: No, there is no set description. It is easy to get cynical about so many books being published, but I think it is important to realize that not every photography type works in the medium of the photobook. Sometimes it is perfect if you make a series, and it is published in a magazine, like in a 16-page editorial, which may be the perfect medium. The most important thing is to find your audience and your medium. Right now, everybody is talking about photobooks, which is great but it also makes it seem that as a photographer you have to make a book, and I disagree with that. Some photographs are beautiful as single pictures on the wall, maybe even better, they don’t necessarily have to be in a book. You don’t have to push everything into a shape of a book. It should fit in a book and with the content, if you need the slowness of the medium of the photobook, then it works very well.

Manik: Would you agree that it is in fashion for a photographer to make books, or more like a need to do so?

Hans: I know for a fact that at one of the art schools in the Netherlands, it is taught that having a photobook is important and works as a sort of business card. If you have just graduated, and you have a book, it is great to send out. With some people like Rob Hornstra, who made his first book, in an edition of 250 copies, it became really well known. At his stage, it worked, and it was appropriate to show his work in a book, but that does not mean that everybody needs to make a book to be visible. If you make audio work then you can make a beautiful website or a blog. Find the right medium for your work. I never liked those portfolio books, as I don’t know what to do with them. I can imagine that with all those dummy awards and things like that people think that if they don’t make a book they will be invisible. There are many beautiful opportunities if you do have a book. You can send it to the dummy awards and people like you see it. There are a definitely a lot of books out there, and it is very inspirational, like when I go to art book fairs. When I was in Arles this year, they had this table, which was never-ending! (laughs). In one year all these people submitted things, so there must be a longer list of people who didn’t submit, and that’s only the photobooks in a single year! It was almost a mile long! There were beautiful things there as well as a lot of things that were a big act, which perhaps would have been great on a website or in a magazine.

Manik: Do you think that the pressure of having your work in the physical form, to show to your audience is the reason that everybody is making a photobook?

Hans: There are many opportunities if you have a book. I can imagine that a few years after graduating a person may feel that they can send it to people more easily as it is not so easy to send a portfolio. People make websites and send a link to them, which I also get. Sometimes you may click on the links, however, a book is something that when you give to somebody, they have to react. I think there is this idea that to be visible they have to make a book, which is also somehow true. That is the tricky thing. If the content doesn’t fit in a book it only backfires on you, in the end.

Manik: You’ve been on a couple of juries and have seen some beautifully well thought of projects transformed into books, but, you have also seen many projects that do not work in a book format.

Hans: Yeah that is true. With a lot of these juries there is already a pre-selection. So I can imagine that there is a lot of frustration in selecting the content. I like being a juror as I get to see some books that are like gems, made by people you have never heard of. That is probably why the most important thing of a book is the engagement with the topic. If you make a precise book that shows that you are engaged with the topic or with the medium, then it can have a big impact. Then it doesn’t matter if you are an unknown name or a very big celebrity photographer, or if you have just graduated because it can be a great medium to make your point.

Manik: When you were on the Unseen Dummy Award jury, the conclusion was that a lot of dummies sent were perfect in a way and there was no more space for a designer to collaborate and explore further. As a juror and a designer, is that a problem or not?

Hans: Well, as a reader or somebody who browses through photobooks, it is not a problem, as a designer, however…a lot of these books are made by photographers themselves. They even look like an archetype photobook. When you collaborate with somebody, however, it can open up more, and you can be more precise. Of course, there are many examples of people doing everything themselves, and it turns out beautifully.

Manik: Those are exceptions. Those are very rare exceptions.

Hans: Those are exceptions. I never really know how to handle these hermetic photobooks in which everything is fixed, and everything is perfect. I like some openness and simplicity. I also don’t like to see a movie or to look at a documentary that tells me how the world works. I want to see, hear and read things that trigger my own opinion about how the world works. That is what I look for in photobooks as well. Don’t explain to me how people in Poland do their laundry, just show me and I will make up my own story, my own perception; I like it when things are more open.

Manik: So is that your message to all the people who want to make photobooks or get their photobooks designed?

Hans: Personally, it is something that I like to look at and read. Books that inspire me and become part of my brain are those that are somewhat uncomfortable, or have open ends. If I’m a photographer and I go to the forest where I make a series of photographs of people wearing pink shirts. Then I don’t need to see the pictures; it is already too hermetic for me. If, however, with all those pink shirts there are one or two blue or green, then I would be interested because it would make me think about what is going on. For me, if things are too dogmatic, then I don’t know what to do anymore. There are people who think the work of the Bechers is about uniformity. What they don’t get is that their work is about the exact opposite: variety.

Manik: So, like everyone you also enjoy the sense of curiosity.

Hans: Yes. Why do you need me as an audience if it is so super clear? ‘Commonness©Dieuwertje Komen’

‘Commonness©Dieuwertje Komen’

Manik: Your books often challenge a new way of looking at the body of work, and looking at photography itself. For example, ‘Commonness’ (Dieuwertje Komen) is about new landscapes created through the physicality of the book. How much of your work deals with challenging the act of viewing itself?

Hans: That is something that I always work with because a book has unique physicality…you have to turn pages, and the pages are connected, so you have a lot of ways to use the physical aspects of a book, rather than if you simply put photographs in it. It is one of the tools that I like to use because you could bend the rules of how a photo could be in a book. My goal is to get the attention of people looking at the book. For instance, with ‘Commonness‘, you want to turn the next page because you are curious about what happens next. There is a narrative and a conceptual idea behind it; it is an essay about the urbanization of all these cities and uniformities, etc. Photobooks work best if there are more layers. So you have a visual layer, but that visual layer should trigger you to think or to come up with your own story or even make you look at routine things differently.

Manik: The work ‘Cette Montagne C’est Moi’ translated completely differently as a book from the initial work. What was the whole process and how did the final edit come along?

Hans: The final edit in that book is super dogmatic… (laughs). It is a series of coal mountains photographed in a certain city and then the names of the cities are also the names of the works. I put them all in alphabetical order, and the countries are also alphabetized. The edit is almost default. What was important was using black paper as a starting material. That was a reaction to the work of the photographer because he took coals from every mountain he photographed. He made pigments of them, and made coal prints. Every mountain is printed in its own substance, so it starts with a super black. If you have a brick of coal, it is a beautiful material because it sucks all the light. I thought that we should use the equivalent of that – black paper. I wanted to do with paper what he had done with photography in the dark room with his pigments, i.e., he brought light into these coals. We came up with this inverted way of printing which creates images, which are indeed not pure reproductions because the colours are much different, but somehow the edit is the same. They are there now on display here at the museum for the first time together, so you see the coal prints, and you see the book. Both images are not easy in a way, you see a contour and you have to take an effort to see the details. You have to find the right angle with lights. Similarly, with the book you have to find the right angle to see all the detailing. Another important thing for me in this book is to have all the images go around the paper, so one mounted edge and then immediately next is the next one, creating a new landscape, which I think works very well. If you have every spread like one image, that wouldn’t work that well as an edit as it would be too boring.

‘Cette Montagne C’est Moi’

Manik: What things do you make sure is part of the editing process when you are working with a photographer?

Hans: The most important thing is that both the photographer and I feel open with each other to talk about anything, whether it is about the edit, or about the photography. I ask questions about why they have done certain things like desaturate images. Likewise, I expect people to question me as well if they have any questions about decisions I make or ideas I have. There should be an open discussion about anything, whatever it may be, whether it is about publishing, about financing, about distributing, about where does all the money go to, where does all the money come from. Everything should be transparent and open for discussion.

Manik: Yet again a very recognized book, Ametsuchi makes the viewer experience something of the existential questions of life, death, and religion that Rinko Kawauchi was dealing with when creating the work. Tell us about the experiencing of working with her to translate these ephemeral emotions into a tangible book.

Hans: I knew her work when Aperture approached me to design this book. I was happy when I saw the body of work that they wanted me to make a book with, as I really liked it. It was a bit dark and very filmic sequence even; and in the beginning, it was about this burning ritual with the flames on mountains. Then she included more images that were suggested, or created various layers. I was working on the edit and the design of the book, and there was one image where you see this one hill, which was in a lot of images. She documented the flames going over the hill, so it was a bit yellowish green turning into a complete black hill. There was one image of a white hill as well. I thought something went wrong and the image had gotten inverted while sending it to me digitally, so I inverted it. Then I saw that it was a snow landscape instead of a missing inverted image. While inverting it, it went from a virginal, snowy, beautiful landscape into a completely dark landscape, which I found interesting. I started opening images, which were of fire and inverting them, and the fire became water. I thought that on a different level it made a point that she was trying to make. So I made a proposal to Aperture and Rinko, I made a dummy and filmed it as Rinko was in Japan, I was in Amsterdam and Aperture was in New York. Two people were always awake, and one was sleeping, (laughs) it was quite inefficient. However, it worked well in the end because by sending mails with movies and pdfs, people could then think about it and didn’t have to inhibit themselves. For me, it was important that both, Aperture and Rinko embrace this idea and see the quality of it. We talked about whether we should do it with all images or with only a few. In the end, we only did it with images that included fire and light scenes because it adds something when night becomes day and fire becomes water. When I first showed Rinko and Aperture I hadn’t expected such a reaction, but they both saw the quality of it and embraced this idea fully. We then thought of how to use this idea in a book to make it work. Practically it meant that most times we talked about the edit you see without the inverted images, so the regular edit, and then later this layer was added on the inside of the paper with the inverted images. It is one those ideas that when put in a group forces a reaction. In this case, everybody was enthusiastic. It was nice to work with her. She came to Amsterdam to get everything on the press as it was printed here in Amsterdam. I had met her once at Paris Photo, but it was the first time I met her for a longer period. It was funny; it was a virtual collaboration going on through the internet. But then again, we are talking now as well, a perfect conversation without sitting two meters next to each other.

‘Ametsuchi©Rinko Kawauchi’

Manik: Was it the first time that you worked with any Japanese photographer?

Hans: I am now working with Yuji Hamada, but yes, that was the first time for me.

Manik: Okay, it was something that was quite incidental that came out and was made into such a beautiful book.

Hans: Yeah, it was. It was. I had known Lesley Martin from Aperture, already for a bit, and both Aperture and I had expressed our desire to work someday with each other. Then Rinko came up with the idea, she had seen some books of mine, which she liked, so it was a group that wanted to work together. For me, it was perfect circumstances, as also with the work. We are now working on the second book, which I’m looking forward to as well. It will be completely different as it is a different body of work and requires a different approach.

Manik: One of my favourite books from 2014, Petra Stavast’s ‘Ramya’ is a complex work involving video and photographic works made over 14 years. When working on it as a book, how did you translate the experience of deconstructing an identity and disseminating it over physical pages?

Hans: Well the start of that was when she was graduating in 2003 if I am correct; she made a little book herself of 64 pages, of 6 by 6 images.

Manik: I saw that on her website. It is still there.

Hans: Yeah, and I always liked the edit. The first 64 pages in the book are identical to it; I only added on the right page. On the left page, there were some images from 2012, when Ramya died. Petra photographed an abandoned house, which was somehow related to the images that you see as 6 by 6. I put it on the other page, that was basically the start. It was one of those projects that evolved because we didn’t know if it would work as a book as it was so diverse. I found footage, small amateur analog pictures, or digital pictures from her working on the street, or of the neighbour, or the works of Petra. There were so many layers that we weren’t sure would work together. We made several chapters initially and in the end, it worked out quite well. Different chapters had to be used, which makes sense because it is not so hard to think of a way to include archival images together with photographs made in America in the 80’s. The several chapters were not what it was about, but more about how to get from one chapter to the other. That took quite a long time and in the end, the conversations Petra had with 3 of her friends and the people related to Ramya, became important as it brought everything together. Until the last moment that it went to press, we were looking for the right shade. The cover had so many variations, and the quality of this yellowish linen…we had no idea what kind of material it should be. Then in an old pile of canvas, I found this stack of linen that had an old stamp on it. The printer traced it to a factory in the Czech Republic. They were to close down in a week when we accessed it. So they could buy a few rolls of this canvas. With everything in this book, it seems that it is somehow meant to be. Some books you immediately know the direction, and then others you start working on it, and then you can made a book in a week. With this kind of book, I knew that it would take many hours to find out how the book should be; but then it is really rewarding if it turns out as it did in the end.

‘Ramya©Petra Stavast’

Manik: Did it take over a year to finish it?

Hans: Yes. Of course, we were not working on it every day because it had so many layers. It is good to then work on a project for a week and then let it rest for a few months, and then work on it again. Petra had gone to America to photograph this in Oregon, to make these photographs; by then we had started working and thinking of how the parts could be. She already had the book in mind when photographing in the United States. Some things also happen while designing the book. When we had all the archival material, I started zooming in on a few images to personalize a few people, instead of constantly having as group of people. Petra was triggered by this idea and went through all archival pictures, looking for women who could be Ramya. If you have the luxury of working on a book for such a long time, then you can inspire each other to make new works in a way.

Manik: That also clearly shows that if you like the project, and you get along with the photographer you are ready to invest as much time and effort as required

Hans: That’s what I like about my job (laughs.) Yeah, for instance, Dieuwertje came to me with the Commonness series. She had already done so much research about uniformities of big cities, and she handed me all the research, which was great. Somebody did a lot of research on a topic that I didn’t know so much about, and I dived into it. I didn’t know so much about Rajneeshpuram, but Petra told me about it. It is a luxury to have all these things brought to you as content and to dive into it. Of course, I relate to some topics more than to others, but, in general, the people I work with come up with interesting topics. It works best that way. Interesting people always have interesting content and I am already curious for Stephan Keppel’s new book, or Jaap Scheeren’s, whatever he makes is always interesting to me.

Manik: Do you have favourite photographers?

Hans: It is nice to be surrounded by them…. I ask them about their work, and it is always interesting for me to engage with them…definitely.

Manik: Please comment on your quote, “Sometimes you have no need to think too much out of the box to make a normal book can be perfect. Sometimes reaching a sort of symbiosis between photography and design can lift the work.”

Hans: By this, ‘don’t think too much outside the box’, what I meant was that sometimes it is distracting. There is a balance that has to be found, it needs to get the focus on the content. If a super straightforward book should be made, then do so, and that can be enough sometimes. The other part is that if for instance, again with Dieuwertje Komen, this Commonness, if you work together, it can really lift the work by making a book. Her work, she showed this as light boxes in the city of Brussels, it was beautiful. If you had put only the pictures in a book with a caption, I think it would work for a very specific audience, like architects who are super specialized. If, however, you want to reach a bigger audience and make it a bit more poetic so to say, or less clear, then the way we have designed it with images, with photographs continuing into another photograph, can lift the work, creating a new body of work that’s in a book that adds extra value to the original photography. That can also be a brilliant text or anything. You are on a team if you make a book. You are a designer, a photographer, a lithographer, a painter. You are sometimes a writer, and all those parties can lift the project.

Manik: The message here is very straightforward, that you need not necessarily always try to do something different. Something that is really plain and simple with a strong, contrite and meaningful book format can also work.

Hans: Yes. That is a love-hate relationship I have with design, in general, that if I am confronted with the design too much, for me, as a reader I think okay, never mind. I want to be confronted with the content, however. The design should lift the content and sometimes it works the other way around. It sounds very strange if I make a book with all black paper, but for me there is always the line on which I always try to balance. That was the case with this black book, it is a good example because it was awarded for many things, but a lot of these awards were for design and a lot of focus was going to the design. I talked with Witho the photographer about it a few times as I felt a bit uncomfortable with that. However, it is always how these things work. You bring something into this world, and people receive it, but you cannot control it anymore. You can only control it until the moment that you put it out into the world. I had wondered at the time if it was not going over the top by using black paper, but then Witho convinced me that we should do it as it created a new body of work. Similarly, with Rinko Kawauchi, I wondered if putting another layer was taking away the focus from her work. I need the confirmation of the photographers to do this. In general, I always try to find the most straightforward design. That may sound strange, but that is what I aim for actually. Most of the books I have worked on have had only one design decision, and then the rest is basically an image on a page. For me, that is my perspective.

Manik: Your books are often more than just the artist’s work. How do you combine the various aspects of design, printing, binding, etc., so that the book becomes more than just a carrier of work without overwhelming it?

Hans: Again, that is a balance, but it is also just making dummies, constantly making prints. When I am work on a book, the printer is constantly printing. If I try something on the screen then I make a new print, often in this, I use small thumbnails to see if the edit is right, and then I start cutting it. If I think that it’s almost right, I glue it into a little book. I ask the printer for a quote, and if he would be okay with making a dummy. Then it becomes more physical, for instance, here I have something on the table that is just a copy paste of a book. It has been in my line of sight for a week already, if I still feel comfortable after two weeks, then I think the design works. However, it needs some time. I’m constantly surrounded with these kind of prints everywhere. This is something I have been working on for some time; this is the first edit.

Manik: Got it. Thank you.

Hans: I have the printer making these kinds of dummies to see if things work, paper wise and if the paper opens well. So it needs to grow. I need to surround myself with physical aspects of the book. My closet is full with these kinds of things. This is like a photo wall type, something that I make if it works as a cover of a book. That’s how I work; I like to visualize the project.

Manik: How many projects do you work on at a given point?

Hans: Oh, that is a good one, let me check! (laughs) I don’t know; I think 8 or 9. But of course, your focus can only be on one project at a certain time. For instance, for the past weeks I have been working on a project about the making of the American Landscape, in collaboration with Marie-Jose Jongerius. I’ve been ignoring mail, phones, everything and just focused on this. Then in the evening, I check emails and things like that. Sometimes it is also good when I make an edit, and it rests for a week while I work on something else. I try every day to work on just one thing. I also work for museams and architects and things like that, for instance now I see a mail coming in about needing new envelopes.

‘American Landscape©Marie-Jose Jongeriusen’

Manik: (Laughs)

Hans: So, I need to do those kinds of things as well. Time management is not my strongest point.

Manik: You clearly execute your projects well. Everything seems to work to your advantage because we get to see beautiful books.

Hans: Yeah, thank you! (laughs)

Manik: As a designer and as a publisher of photobooks, do you feel that collectors or reviewers are controlling the reins of which books are noticed and which do not, or which are winning the awards and which are not?

Hans: That is a good question. It is something that I have been thinking about for quite a while, and I don’t quite have my head around it. For instance, the books we publish from Fw Books, they like the book with Stephan Keppel…it’s crazy, two – three people put it on the website, it got shared so many times, and then in a few months the book got sold out. That for me is also a problem because I want to take it to the fairs and Paris, and sometimes these books don’t even last half the year, or even a year; and then other books, they take much more time. What I’m sometimes critical about is that if the books that are really in the photography book market, books that are a bit more difficult or take a bit more time to digest, they are more easily overlooked and those are exactly the books that I like. I always feel like a bit of an insider of the photobook world but also outsider because with all those things that are picked, I think I understand why. It’s a bit like with ‘The Black Book’, it is not on display at the museum in Amsterdam, and they asked me to give books to them so that they could consider it for the exhibition. Then I thought, of course, you picked the black one, it is a beautiful book, but there are more interesting collaborations going on, which are not that obvious and are a bit more hidden but are also really valuable. The thing I am a bit more ambivalent about is that it is great to have all this attention about books. In that sense, I think I also agree that not everything gets the right attention, some things get too much attention, while others, less. It is not mathematics, it’s not 2 plus 2 is 4, it’s more about taste. It’s great if you are selected, and it’s a pity if you are not. However, it’s not always that if you are in the top 10 books list, that it is one of the top 10 books made. Imagine if you made your book very carefully, and you are not on one of the lists, it must feel bad and you’d think that he book has failed, but that’s not the case. I think if you can reach out to a specific audience that is what matters. For me, it’s great how the internet and these things work. Sometimes if you put something on Facebook, we see that only a few people see it, and sometimes it is picked up and cross posted and shared 300 times, and I don’t know why. You cannot influence, so you shouldn’t try to influence. You shouldn’t think about it too much. Every time I think about it, I want to forget then about these dynamics, the lists and whatever. It is something you cannot influence, and if you are focused on it, you will have either extremely good energy or be extremely depressed if you depend too much on what other people think. I have a few books we made which almost didn’t get any attention, but they are still really good books, so it’s okay.

Manik: Do you feel that there is a certain level of dictatorship in the present photobook world, which does not create opportunities for many others?

Hans: Yes, this is true, but I think that’s a part of how a book world works. It is a curated world. It’s everywhere that you can have a book…you can put it on a website or a blog, but it’s always a book in a curated environment. If it’s Martin Parr’s selection, but also a book show. The book show doesn’t put all books there; they select. Like for instance, Dashwood; David Strettell does not blindly take all titles. He selects –as any other bookshop– what he thinks works for his audience. I wouldn’t call it a dictatorship, that’s how it works. I was talking to Stephan Keppel two days ago; his book is almost selling out, and I am one of the publishers who are annoyed that the book is selling out too quickly. I like to have these books and to bring it year after year to the table in Paris because I think they are good, and I hate it if I cannot show it to people anymore. So if things are selling out then, I am always like, ‘Shit! What should we do? “

(Laughter)

Hans: I don’t want that, and I am happy that it is not always in all these lists because it slows down, and all the books we make, one day or the other will find their public. Some books do it in a few months, for example, this book from Awoiska van der Molen will sell out soon. For the first time we are working on the second print, and other books will take 2 years, but they will find their audience, and that’s fine, and if it isn’t on the ‘Best Book List’, then it will get all the individual attention. That’s how it works. ‘Sequester©Awoiska Van der Molen’

‘Sequester©Awoiska Van der Molen’

Manik: Many photobook connoisseur pick up their choices and take a book from nowhere to the top. Many books that are not discovered by them are beautiful books, but do not get well-deserved attention. I personally feel that this a big problem. I call it a dictatorship, you call it curated; I understand of course.

Hans: I have no idea actually. When I was in Arles this year where we also submitted our books, I saw books that were represented; there were many book venues here there, and there was a lot of attention for the books. However, when I had gone to Arles for the first time, about ten years ago, there was only Markus Schaden, there were a few tables, and he knew everything about the books he was representing. Of course, he couldn’t show everything, and there were fewer photobooks than there are now, so it’s not easy to compare. I was wondering what happened to the simple life when Markus was here with his three tables. It was important that he took the book with him to Arles, so we got a contact with him and tried to get him enthusiastic about it. Of course, he had the final say in showing or not showing. There are good things to say for this kind of way of working and there are things, which perhaps, are not so healthy about this way of working. Again, however, maybe I’m not the right person to talk about it because if I go to a book fair, I’m almost paralyzed at the sight of all these people and all the stands and the many books on every table. When I go to the New York Art Book fair, I don’t know where to start or where to finish, after three tables, I’m exhausted. Then we all discuss about the interesting publishers, and select ourselves as an audience. But I think it’s okay to have these ambassadors, dictators, curators or whatever we may call it. Then again, it’s nice to find something beyond those channels yourself. I have a few of those books that are totally unknown, but they are very dear to me because I found them and was struck by what I saw and how it was done. Those are the books I really engage with, and I don’t care how many people showed it or that I didn’t hear about it.. It’s good to have this critical approach to the whole dynamic.

Manik: What are your views on ‘Self-Publish’?

Hans: With self-publishing, in general, I think it’s beautiful that people publish whatever they like. What I referred to before, what I think is that not every project works as a book. By taking out publishers and doing everything yourself and in a small scale it’s also…I like the extra filters that are there. If there is a publisher and distributor involved, there is more time. It takes more money to get into a network. That is very valuable and makes things clearer. For instance, if we get projects that are interesting, but I may think it’s not something that we, as Fw books, should publish because we have a certain focus, and people know this focus. People come to our table, knowing us; they know how to look for books that we publish, and I think every publisher has this kind of focus.

Manik: A taste or focus?

Hans: It is a focus. It’s about getting your work there and getting it visible because there is so much you need to have certain filters. You need to create them for yourself or other people, or you just trust your own creative instinct. To be honest I never get it, just going through the top 10 list of best books of 2014 and then not even looking at it, just ordering, ordering, ordering. I can’t relate to this, and I think it’s stupid. If you want to see a book, if that is the discussion then I totally cannot relate to that. If we go a few times to these fairs, then for the first time they see it and they come around, have new conversations about what your books are about, and want to see any new projects that you are working on. I like those discussions because they are about the projects that you show, and on general topics. It’s about photography, and photography and books, or engagement and things like that, so that’s how it works.

Manik: What are your views on limited edition photobooks? On the one hand, it is more personal and intimate. On the other, it has become a strategy for many young photographers to produce only limited edition copies, which are instantly sold out, and, therefore, exponentially more expensive.

Hans: I know a few works in which this works well, but if it becomes a strategy to catapult the work forward easily, then for me that doesn’t work. When we published a book with Awoiska, we could never have published without making the limited edition, which meant, making framed prints with a book. It sold it for around 800 Euros I think. That was a personal approach from Awoiska to collectors, saying ‘I’m working on my book, do you want to buy my limited edition?’ And it was also because they liked the print together with the book and then if 20 people do so, we could print a book. So that is one way of having a limited edition, to get it financed, and to publish a book. With Awoiska, we found out that people liked signed copies which we had never had that before. Every time we publish a book, I have one box signed by the artist, but this time it was sold out in 2 days. Awoiska went to Japan so I had to wait for her and when she returned she signed another 100 copies or so because people kept ordering. Then put it on our website and made it 10 Euros more for a signed copy.

Manik: Yes, I noticed that on your website this morning.

Hans: Yes, it was the same actually, but it is quite a lot of work to have that. We have to be very organized. The first time we made it more expensive, it felt strange to do so. I have always liked having a signed copy, as with a novel. I always like personal moments, like when you are with a photographer, and you express your appreciation for their work and ask for a signed copy. For me, that is a signed copy. I don’t want to spoil my own market because I sell signed copies that are presigned. People really like it but I’m also not sensitive about such things like our first print, second print…I don’t care. If I want the book, I want the book. I don’t care when it was printed and a lot of times the second print and 3rd print are even better because then they can adjust the mistakes made in the first print. ‘Bible©Momo Okabe’

‘Bible©Momo Okabe’

Manik: I will give you an example; do you know the work of this photographer, Momo Okabe?

Hans: No.

Manik: Well she is a very talented young Japanese photographer and I personally admire her work. Her first book was ‘Dildo’, which had only 55 copies. Okabe’s latest book ‘Bible’ has 300 copies. Her idea was that all those 55 copies were handmade, and because of that reason, it was limited. Again, there are advantages and disadvantages but I’m more curious to know from you because some photographers are taking this as an excuse actually to monetize the marker. All these limited editions are really expensive.

Hans: With all due respect, I don’t know. A book is produced by machines, and not by a person. I’m not super interested in books that are handmade. Of course, there are always exceptions. Nevertheless, a book is something that is mass produced, and that can be 2 or 3 hundred copies, but you have to…otherwise it’s not a book for me. I’m very open-minded, but that is one of the few limitations I have. A book that is hand sewn or whatever and then all these creative tresses and things like that…it works best if it has to do something with an idea or a concept. You have an idea, and you have a concept and you have consequences. It is the easiest thing in the world, to come up with an idea. The tricky thing is to confront the consequences of that idea and to put it into production. You can make anything by hand so if I see those things on the table I’m not interested, and I move on. I understand your question but then, I think it’s indeed silly because it is also super expensive. I don’t get it when people think that printing a book is so much and they want to earn some money, so if it is 10,000 Euros, and they make 5 books, then it will be 2000 Euros for every book. I think that is not how it works if you want to make a book then just make an effort to get it there.

Manik: No, but also I feel that some publishers are.

Hans: Then just make a translation if you want. Making a book is a translation, and it’s about using techniques that are there. For me, a book is something, which has more copies, and the quantity doesn’t matter. If you make two copies or 200 hundred copies, it should be the same result.

Manik: I was talking to someone at Paris Photo in 2014 and he specifically mentioned that 5 to 7 years back Steidl used to have a limited edition on 3000 copies.

Hans: Okay. (laughs)

Manik: The joke of having a limited edition of 3000 copies, but now a limited edition of 100s or less. Some of the publishers are also doing this not just individuals or photographers.

Hans: Yes that’s true. For example, this book of Alec Soth, published by The Walker Arts Center, in the back, it has a sleeve and it’s a lot of work. Again, that’s what I talked about, you have consequences. There is a concept that you think ‘oh it’s nice to have a book there’, and it is probably machine made, but at least it’s an effort of inserting something extra, but then if you are willing to do so, 3000 times, then also you have my respect. I don’t know where the copies are made; it doesn’t matter. It’s also a mass produced thing. Like the first book of Petra, where we hand-wrapped everything, about 750 copies. Of course, that is handwork, but more in the effort of engaging with the print run, with the machinery and the systems that are part of the whole, part of making a large print run. If you feel like stapling everything for a 1000 times, please do so, but if you can do it only three or four times, then that’s easy. Making a book is putting consequences to your ideas, and it may take time effort and money, but at least it takes something. A few years ago, you had this print thing online where if somebody orders a book then they pay, you print, and you send it, you don’t take any responsibility for it. It’s full of boxes here, but it is great to have all these physical things, then every time I am confronted with it I think that I should get them out there otherwise nobody will see them here. They need to go to fairs, to stores, and people should see them. It’s good if a book has many copies, at least 500 or something.

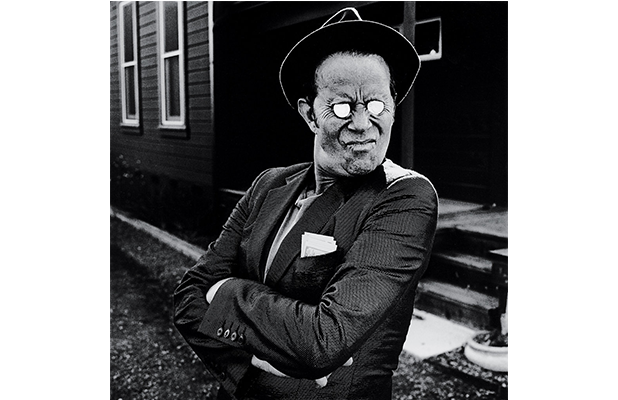

‘Tom Waits©Anton Corbijn’

Manik: What according to you is a limited edition number?

Hans: The definition is that they have made these many copies, and they will not make more, so it can be 300 if you have numbered and signed all of them, and then it is limited. Alternatively, even if you say it is limited like the book about Tom Waits by Anton Corbijn, which was published, and had a ‘limited edition’ of 6600 copies! That is a bit ridiculous.

(Both laugh)

Hans: Only if you say, ‘We will never make a second print’ is it a limited edition. Roma Publications makes a few limited editions where you get an original photograph with it and are sometimes printed in 400 or 500 copies.

Manik: What according to you will the future of photobooks and photobook design? Will it be more like the book or more like an object?

Hans: My answer to this question will be more of what I hope for than what it will be. Books that are made should get the focus back into a book and it should not be a rote thing to ‘put everything in a book’. I think people will also find out that that that is not the right way. I have worked for about ten years with photobooks, and got a lot of benefits when it gets the attention for photobooks. In 2008, we made an exhibition at the photo museum in the Netherlands, putting photobooks next to each other because I felt the urge to see photobooks together on a table. It was hardly ever done that way before. This was 6 years ago, right now you can hardly imagine that you can feel the urge to see photobooks next to each other because now there are so many reasons to show and highlight photobooks and to talk about them. I have no idea where it will take us to because many of these things are getting into a routine. It was at the Paris Photo Photobook Awards, Kassel where we made this exhibition in 2008 or 2009. The concept exploded, but I think within this explosion now, there is a sort of proportion that attracted a larger audience, a bigger question, so you need the kind of scale that it has now. I also think it cannot grow that much bigger. Practically speaking as a publisher, we go to about five fairs in a year. We cannot go to ten because then it will be a full time fair. I think the scale is now quite big, and shows space for independent publishing, and for many different types of photobooks. I hope it will remain how it is. Many people think it will collapse again, but I’m not one of those people.

Manik: Exploded?

Hans: It can’t explode but the bubble got bigger, and there are more people who want to go into the bubble. More people are interested in the medium of photobooks, so it’s okay that it grows, it’s a natural thing. I hope that photobooks as a species will take an effort to connect with other books as well. Sometimes there is a lack in photography in that it stands too much by itself. It can easily be a part of the architecture scene, or art scene or theater. I think that’s the one weak thing with photography and photobooks: that it’s too lazy to connect to the ‘real’ world. It’s only about photobooks. Things that people think are pushing the borders of photobooks in 2014 had already been done in the 1970’s, in art books for instance. Sometimes, there is a limited view on photobooks. What I hope for the future of photobooks is: Stop acting as if they are a species by themselves and just behave, and become part of the whole scene. Come out of your cage and join the rest of the zoo!

Photography Interviewed by Manik Katyal

Research by Adira Thekkuveettil