United Kingdom –

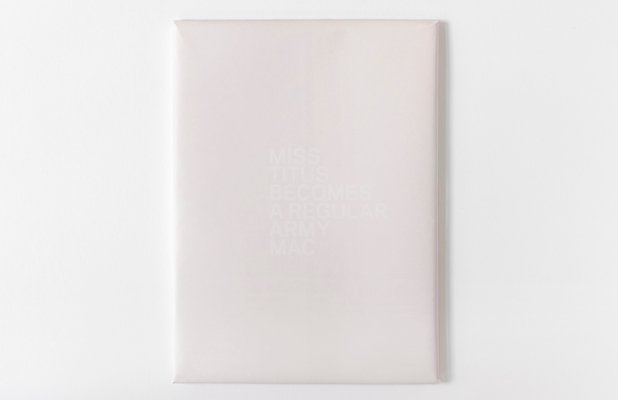

Photography feature- Melinda Gibson’s new book, Miss Titus Becomes a Regular Army Mac is a book about a collection of photographs, a response to a collection of photographs or an examination of how that collection has been used. Or perhaps it’s all those three things. It’s hard to tell.

The collection in question is Brad Feurhelm’s. Feurhelm’s collection is one of photographic curiosities, the marginal and offbeat.

So Miss Titus is an investigation in some way. The first thing I notice about it is the beautiful packaging. The first layer is loose tissue, the next is orange paper (with the title mirrored in white) and then more tissue stuck with orange stickers (like the ones you get to mark sold works at some exhibitions).

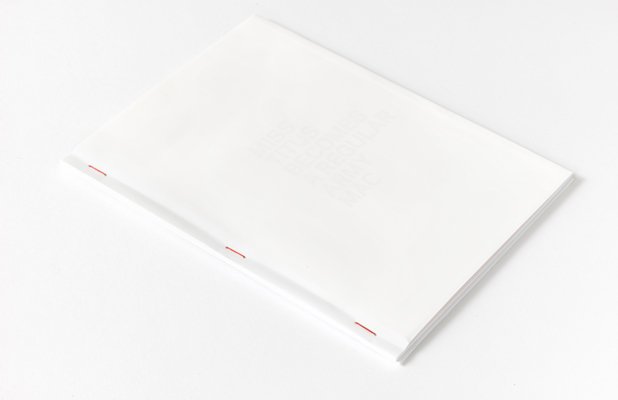

Then I get to the book. It’s a small book, which is bound by three brass staples at the spine. The title is written on card that appears beneath translucent paper that has been folded over and joined at the spine. Oh and look, slip your hand into the gap and the title is on a card insert that pulls out. There’s an explanatory text but it is kind of dense and it’s too early in the morning for that – so I put it to one side and move on to the book which is a far more transparent way of reading the text.

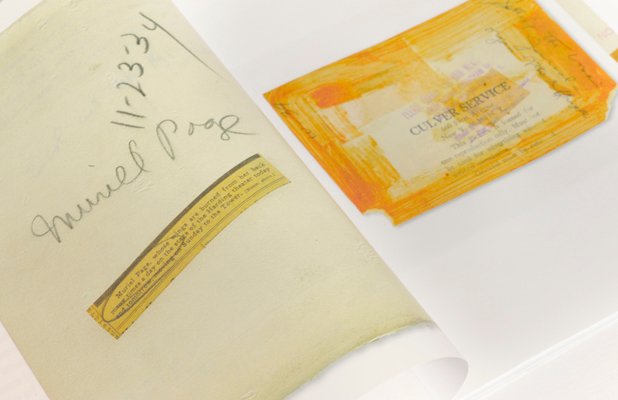

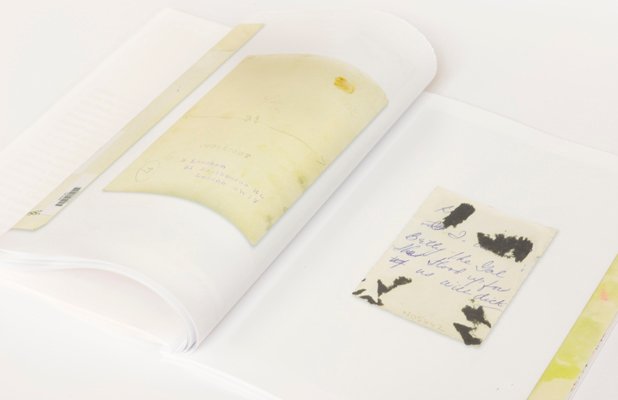

Inside the book I don’t see the pictures that I expect to see. Instead I see the backs of the pictures I expect to see, complete with titles, notes, addresses, bar codes and credits. There are pictures with traces of glue on them, showing they’ve been ripped from a scrapbook or album, pictures from digital printing sites, pictures or porn stars that are FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY NOT FOR PUBLICATION.

These draw me in, but still I can’t see the pictures because, with only a few exceptions, the pages are folded over and stapled at the spine. I bend the folds and sneak a peak but that’s kind of unsatisfactory. So what do I do? If I cut the pages, then I destroy the book, but if I don’t then I don’t see the pages but at least I preserve the book as the collected fetish it is supposed to be. And it is supposed to be that – the special edition is even for sale in the Louis Vuitton Maison Librairie in London, something which transforms the fetish into something even more vulgar than the collectible photobook and has me gagging to get my old puritan hairshirt and scratchy underpants out. LV? What does that packaging do to the book?

Anyway, back to the book. The folded over page format is one that has been used in a number of photobooks in the last few years, most notably by Ben Krewinkel’s A Possible Life. Here the visible pages show the official documentation and immigrant identity of Gualbert, a migrant to the Netherlands. Cut the pages open, and the friends, family and hopes of Gualbert are revealed in a series of personal artefacts. The impoverished, depersonalised Gualbert become a real person, his Possible Life came alive.

And so it goes with Miss Titus. The visible pages show the hidden dynamics of the pictures; the notes and the traces of their lineage. They tease me into wanting to see the pictures underneath, they make me work for the pictures, make me invest my time in hypothesising about what lies beneath. They make me agonise about cutting the pages open and wrecking the book. Or am I wrecking the book? Perhaps I’m just modifying it in some way? Perhaps I should do what I did with A Possible Life and have two copies, the cut copy and the uncut copy.

So after an inordinate amount of time and consideration, far more time and consideration than I normally give to photobooks, I get cutting. I can see a shadow of the first image on the visible page and when I cut, I see the original. It’s a picture of a semi-nude woman (from Hawaii maybe) wearing a garland of leaves around her neck. Opposite there’s a picture from Chicago of a semi-nude woman with fairy wings. I go back to the caption. It’s Muriel Page and the visible caption says her ‘…wings are burned from her back many times a day on the stage of the Harding Theatre…’ What does that mean. Back to the picture and still I’m none the wiser. I’ll be puzzling over that for the rest of the day.

And so it goes on; glamour shots, nudes, Grace Slick and there’s the title picture of Miss Titus becoming a regular army mac. Miss Titus is Susie Titus and the picture shows her learning ‘military etiquette’ in basic training in World War Two. She’s shown in a line of women marching towards a mess hall. But which one is Miss Titus we do not know. The title does not tell it all and nor does the photographic composition. For all the guessing and the hypothesising and the close-reading, there is a shortfall in information.

More pictures come. Suffragettes, a kissing male couple and women in service are a counterpoint to repeated pictures of women posing for a male view. One titled Complete Man exemplifies the book. A woman comes off stage from some kind of nude review. She’s naked except for a heart shaped piece of material over her bottom. And as she leaves the stage a man looks at her and she looks at the man. His body is inclined towards hers, his left hand blurred in movement. But she looks right back at him as she walks past him. If he’s the Complete Man, then she’s the even more Complete Woman, almost as complete as the Hawaiian Hula girl who appears in the last picture of the book. This last picture might be produced for the male gaze but that’s not how she’s posing. Her legs are crossed, her arms are down and her hair is down. She is who she is, no matter what the photographer does.

All source material/ imagery is from the Archive Collection of Brad Feuerhelm.

Pages: 46

Place: Zürich

Year: 2013

Publisher: b.frank books

Size: 17 x 23 cm (approx.)

Colin Pantall is a UK-based writer, photographer and Senior Lecturer at the University of South Wales, Newport.