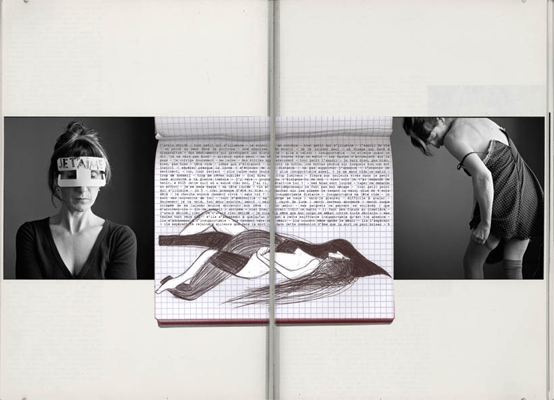

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

England –

It is not an easy task to interview Cristina De Middel after her brilliantly designed self-published photobook, The Afronauts, has been multi-awarded, multi-reviewed and exhibited almost everywhere. Re-imagining the failed Zambian Space Program, as conceived by grade school science teacher Edward Makuka Nkoloso, who produced the equipment and trained 11 Zambian astronauts (and an ‘undetermined amount of cats’) to beat the U.S. and the Soviets to the surface of the moon and Mars by 1964, the artist ‘documented an impossible dream that only lives in the pictures’.

I meet Cristina, a charismatic Spanish photographer, for breakfast in East London, on the Saturday morning, 13th April, 2013, before her Deutsche Börse photography prize exhibition’s opening at The Photographers Gallery.

EMAHO : Since you have been asked so many questions, I am going to ask you a favour: to imagine for a moment to have an encounter with your double, like Borges in his short story ‘Borges and I’, what would ask yourself?

I am not sure, I could ask anything. I think one of the things that’s not easy to understand in the book right away – and it’s nothing to do with the magic of the story or that of Africa – is more: what do I think about the Zambian Space Program? If I think it is impossible or not, because if you look at the book I don’t state it, I just present the story, and don’t say whether they went or not. I don’t, in a way, position myself. So I would ask myself if I think it’s possible or impossible, if it was a good idea or a bad idea. But I wouldn’t know the answer.

EMAHO : Which was actually my next question: and how would you reply?

I think we are not prepared to believe that Africa can go to space, not in 1964 obviously. From what I’ve seen of the reactions to the series, people seem to think that we are just not prepared. I don’t think it’s a matter of technology, because technology is a matter of money, and money is just a matter of decisions.

And indeed Nkoloso was denied funding from the United Nations.

Yes, it’s not an impossible metaphysical project. It’s not that Africa or any other country that is underdeveloped cannot go to the moon. We can all go to the moon. It’s just about political decisions that make us think it was impossible, and I think that it is something we can change, as soon as we want.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : Is it necessarily a good thing to go to the moon?

I wouldn’t go (smiles). I don’t know why would we go to the moon, I have never understood it.

It’s a form of colonialism..

It’s colonialism at its highest level. Also I think we all share this fascination with the sky, the universe, the cosmos and so on, but I don’t think we all share the vanity of showing the others that we want to go to the moon, that we can go to the moon. I think it’s a man’s thing.

I found particularly funny to hear that pieces of ‘land’ on the moon were sold, and that there is a market for that.

I am sure there are a lot of people who would buy it, people with a lot of money in need to redesign desire and desirable things. Obviously to own a piece of the moon is like having a piece of god, it has this metaphysical aspect: you see it, you can’t touch it, you know it’s there…but according to me nobody has been there.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : Could you tell us more about your first encounter with photography, when you were a child?

My first encounter with photography that I can remember, the first time that I considered photography, other than being surrounded by vernacular photography like family pictures and so on, happened because my sister (I have a brother and a sister) was the only one who wanted to be an artist. My brother and I didn’t know what to do. She is very creative and she just took my father’s camera and started to take pictures and I remember my brother and I, who were younger and very close, making fun of her all the time: “Oh you want to be an artist, a fashion photographer?!” Of course my sister now works in finance, my brother is a photography director and I am a photographer too, so things turned out the opposite of what we expected! So it’s because of my sister, and making fun of photography, that I started to consider photography as something one can do as a job.

EMAHO : And what about your metamorphosis from photojournalism to fictional photography? Do you still consider yourself also a photojournalist?

Many people have asked me why, because it’s not that I was very well-positioned as a documentary photographer. I was a staff photographer. I had a good life. People tell me that I was very brave, especially in Spain at the time of the financial crisis…you know to have a staff photographer position and then to take the decision to become an artist. But it was not like that; I could not stand it anymore. It was a necessity; it was running away more than being brave, I needed to get rid of it. For some reason the only thing I asked myself was to make sense of my life. I cannot live doing something that I don’t believe in. When I stopped believing in photojournalism and the media it was like an illness, I felt sick and I had to leave. It was a general disappointment. In my newspaper they loved me, I love them, they are very good friends of mine, they just gave me a prize. When I talk about photojournalism in these terms I am always kind of worried because it’s not about them, it’s something against photojournalism itself on a bigger scale, specifically how the media works, and how they are responsible for terrible things. For example there has been this terrible marketing campaign against Africa, and I think it’s very dangerous. Who controls that? I mean, we’ve already decided some time ago that we have to separate the powers and now we have a very strong power that is not regulated. It’s not fair that someone that is the owner of a big news corporation can decide if Africa is worth it or not for the next 20 years. I know it’s more complex than that, but I do believe that media should be regulated. If you give bad news about one place you are forced to give good news in less than a month. Now that we assume that it’s all about the images and marketing and how you sell yourself and how you make yourself visible, how is Africa ever going to stand out with its terrible marketing campaign? It’s all about people killing each other or dying…who wants to go to Africa? Nobody, because ‘it’s dangerous and they kill you, and there is HIV and they rape you’. This simply is not true.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : Have you ever thought about setting up your own alternative photojournalist platform, magazine or blog?

I like to take pictures and I like to tell stories. I don’t think I can manage a magazine. Maybe in the future, I don’t know, nobody knows. Nowadays I like to identify stories that I think will raise a debate, exploring issues that I think are important to debate, and publish them. If no newspaper is going to publish them, which is often the case, I will do my own publication, which is what happened with The Afronauts. Maybe it sounds very fictional but it comes from a very specific worry of mine that has to do with what is happening now in Africa. This series that was completely fictional has been published much more than any other series that has been, say, denouncing a certain situation straight away. So I think photobooks can be a good platform and also just publishing in magazines.

EMAHO : Your Afronauts received a plethora of definitions, among others, a work of docu-fiction, surreal, a sci-fi photobook, an improbable project that combines myth and reality. Which is the one you think most appropriate?

I wouldn’t say docu-fiction, because it is not fiction, it is a real story. I would say surreal, but that comes from the Spanish and Ibero-American heritage. I am not the only photographer that has a surreal approach. I think Spanish people need that in order to keep on living (smiles). It could be a sci-fi photobook but I think ‘an improbable project that combines myth and reality’ is the most accurate definition. Above all it’s a story told with photographs.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : What does fiction mean to you in allegedly one of the most realist medium like photography?

I don’t believe photography is realist. Fiction is just the most honest way to put it. You reframe, ‘crop’ reality, you take this small slice of reality and turn it into what you are interested. A photograph works like a word in a sentence and you can say what you want, so what you can say can be true, can pretend to be true or can be completely false, but it’s always in the hands of the creator, of the photographer. It is realist because it’s a mechanical representation of reality but this is not reason enough to call it realist. It can be based on reality or be dependent on physical things, but I wouldn’t say it is realist, even if photojournalism on some occasions can do a great job. Especially now, ninety per cent, maybe more, ninety-five per cent, is pure interpretation or subjectivity that responds to a certain aesthetic style of the photographer, of the assignment, of the publication; it depends on so many things, but it’s not about knowing what is really going on. It is impossible to tell what is really going on. You ought to explain everything, so if you just focus on one single part of it, you are already redesigning the whole story, in a very dangerous way. It’s a tricky one. I think photography and truth need to redefine their relationship. Photography is a very good tool to raise awareness, to give highlights of what is happening, but it needs to get rid of this responsibility of telling the truth. It’s just a matter of reducing expectations. In the beginning, when it was discovered, maybe we were all fascinated by the medium, like with the first projection in cinema: everybody was scared by this mysterious thing coming from the screen. It was the same with photography. For example they say this is what’s happening in Crimea, but the pictures are staged. I mean, it is Crimea, there is a war going on, but it’s not really what is happening, and from the images you are not going to understand one hundred per cent of what is happening, maybe not even fifty per cent, because it is just about the surface of things, and you cannot just rely on the surface of things. It is very hard, if not impossible, to build truth. You cannot explain truth by the surface of things, and that is what photography is about. I am not saying it’s a bad medium; I love it, especially because it has this potential, but we have to reduce the expectations. It’s a fantastic medium but it’s not true, it’s not bad, it’s ok, we just need to move on.

This takes us to my next question. I saw on Facebook that you recently quoted Kojo Ngue, the author of the last text in you Afronauts…

[laughs] I am Kojo Ngue!

The Afronauts by Cristina De Middel from DEVELOP Tube.

EMAHO : Fantastic! [can’t help but laughing as well] I didn’t know that, this is sort of a scoop! Is it the first time that you reveal that?

[still laughing] It is actually. People ask me who wrote the texts of The Afronauts? I didn’t write the texts of The Afronauts, it was a friend of mine. When I started to read reviews of the book saying ‘text by Kojo Ngue’, I loved it. It’s a fictional character and I found it very funny.

EMAHO : Is he your alter ego?

In a way he has become my alter ego, but I think I will invite more people to become Kojo Ngue! I make him say all the things that I believe in that maybe I don’t dare to say. I think it’s more interesting that there is someone anonymous that has things to say, otherwise it will relate too much to my work. Some ideas can be shared on a different level than just my own experience.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

I really like the fact that you specified that he was a retired lecturer!

[laughs] Honestly, I just thought about that in two minutes, I was like: ‘yes, whatever!’ [laughs].

EMAHO : How did you come up with that weird name?

It’s funny that you ask. Kojo is the name of my next project and Ngue is the surname of a person in a previous project. No, actually, wait a second it was Nzi. Ngue… I don’t know really [laughs].

Anyway, to go back to my question when you, or Mr Ngue, said that: “As victims of this changing world, Photography and Truth seem to have finished their sentimental hand in hand journey. They have run out of stories to tell on the way and now they look at each other in the eyes, just like an old couple wanting to forget. Truth became a rock star, her manager promoted her wrong, she was sold cheap and she lost her charisma blinded by the flashlights of the media. Photography tried to keep her rhythm (…) and left behind, she started going back to the places they once visited together as a team, relieving her despair by remembering the good times in forgotten wars and far away countries…but alone this time…and with nothing to say”.

Do you think this divorce is recent? What about the XIX and XX century photography that manipulated reality? It was recently put together in an exhibition at the Metropolitan in New York, called Faking it, and curated by Mia Fineman ?

I think that if it is being exhibited in a museum, you are already stating that it is not about truth, but about an exploration of the medium in an aesthetic or conceptual way. Kojo Ngue is deliberately talking about the media and photojournalism, when we started to use photography to document reality, the golden age of war photography, the big mythical photographers, who did a great job at the beginning, because nobody was questioning what they were doing. I am not saying it was not true, but I think the media subverted everything. Now, if you really want to know what is happening, you have to look at social media, like YouTube, and see what citizens of the places in question are actually uploading. The Arab Spring is a good example of that, or even in Spain, when there was the terrorist attack by Bin Laden. The Spanish media were actually blaming the ETA because that was the version of the government, while the media around the world were saying it was Al-Qaeda. You cannot trust the media anymore. Putting photography, which apparently has such an honest approach to reality – a mechanical intervention in reality -in the hands of people that deliberately want to manipulate the public opinion and truth is very dangerous and I think that people are starting to be aware of that.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

This actually reminds me of Brecht’s War Primer. I think he had a similar disappointment with photojournalism, as he had a sort of yearning to add poetry to Second World War photographs that were published in the capitalist magazines of the time, like Life, to unmask reality. Many critics stressed the importance of text and captions to contextualize photography, and protect it from the risk of manipulation, from Benjamin in ‘The Author as a Producer’ to more contemporary curators, like Cristian Cajoulle. Do you think photography is a fragile medium that needs text?

I don’t like photobooks that begin with an explanation of what you are going to see. It’s like if you went to the movies and before the film commences there was a text that explained the story and then you saw the movie. I think photography should be more aware of its potential to tell a story without the need of text. We all agree that still images have this meta-photographic information about what is going to happen next and what happened just before. There are all these tricks you can do with photography, which you cannot do with moving images as they are based on sequence. That’s why I think photography is much more interesting. But when we come to photojournalism it’s completely different, because you don’t want to use this potential of many interpretations and how they can stimulate your brain; you actually want to say something very specific, so in that case I agree with Mr Cajoulle and Mr Benjamin: if you want to really reduce the meaning of your picture and limit it to one single interpretation, you need text. Photographs are so powerful that you need to contain their meaning. I prefer photography to be more autonomous. At this point there is a lot of work to do in terms of how you can tell a story with still images. We have been more focused on using photography as a document. Why isn’t photography respected when it’s about fiction? I really wonder why. For example in cinema it’s different, when you see a movie about aliens that want to destroy the earth and so on, you are not mad at the director because he is showing something which is not true. You don’t expect truth from a movie, and it’s ok.

Yes and it’s interesting because movies also are mechanical reproduction of reality.

They are exactly the same. Maybe we are more used to it, maybe because there is a strong industry, it’s easy to consume, you don’t have to work a lot in your brain, you are more passive. For some reasons photography hasn’t developed so fast. In movies there is no conflict between documentaries and fiction, why should there be a conflict in photography? Why do I have to answer over and over the same question, which I am happy to do of course, of truth about photography?

EMAHO : And what about the way you present text in the book? For example in the article ‘We are going to Mars’, you can barely read the text. Was that intentional?

Not at all [laughs]. It is an article I took from Internet and the quality is poor. It’s a real article. The only thing I changed is Edward Makuka’s face – I just pasted one of my Afronauts’ face. I didn’t want it to be like a proper portrait where you could recognise Edward Makuka. He was the leader and I liked the idea of not putting his face, I don’t like portraiture in an editorial way. I wanted his portrait to be more psychological, I didn’t want to give everything away about how he looks. The text at the beginning of the book is a real letter that I just typed again.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : Did it come with the mistakes as well?

No! I used a really old typewriter and it was really hard to write with it, it took me ages, so I just decided to keep the mistakes. I am always very relaxed with these details and I think it can work. Sometimes you add these things that don’t make sense and I thought it looked good.

EMAHO : Sean O’ Hagan in the Observer titled his article about the 2013 Deutsche Börse photography prize: ‘ A short list that’s short of photographers‘ and defined you a contemporary artist who uses photography as part of her practice. What do you think about it?

I talked to him. He didn’t know that the only thing I have done in my life is taking pictures. I have done other things of course, but I have been a professional photographer for ten years already and he didn’t know that. It doesn’t disturb me. It’s just not true. I don’t care about the aesthetics of photography, I just use photography to tell stories, you can call it as you like. I think visual storyteller is the most accurate definition at this point. I am completely sure that I will move on from photography. I have seen so many pictures, it’s wrong. I think that if I am still telling stories I might find better ways that don’t involve photography exclusively. I am not saying that I will drop photography, but I need to move to something else. On Facebook in six months I went from 1,000 to 4,000 friends and you get a good example of people who actually love photography (they added me as a friend because I am a photographer who is having some sort of success at the moment) and you can see from their posts what kind of photography they are interested in, and I have really had enough of sunset pictures for example. The only thing they say is: ‘look I am such a good photographer’, because ‘I can capture light, I am aware, I am a good street photographer’, that’s the only message that there is behind their pictures. But they are not saying anything, it’s just aesthetics, everybody can do that if they have enough technical skills. But if this amazing tool that everybody can use is not used to tell something, what are you telling me? Photography is like any other artistic expressions… you just cannot paint something because you like the colour blue, and then red…

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

That’s more like a hobby for amateurs…

It’s a hobby exactly, but this happens not only among amateurs. There are a lot of stories that you see, maybe I get in trouble by saying that, for example there are a lot of people who copy Salgado, his aesthetics…

EMAHO : Or more recently Pieter Hugo…

Yes. And what is important is what you are telling. I need to know, I need to understand. I have the same frustration with contemporary art. It should be all about our message; I mean we are supreme communicators, because we use a self-created language, we use a code, but still we cannot forget that we are communicators and we have to communicate something. So if the message gets lost in the way, it becomes something that has no sense at all.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

Yes sometimes it’s more about who arrives first in a place to photograph it…

Yes, but who can do that better than people who actually live in that place? Why do you have to go? There are so many interesting debates now going on because anybody can take photographs even with their phone. What we lack are storytellers and people who engage with the story. Let’s say for example that I am in Chechnya and I come from Spain, what do I have to say, I think it is honest to assume that you are a Spanish photographer in Chechnya before you say anything about Chechnya, but nobody does that, possibly because they are scared of giving their own opinion. For me it’s the only thing that photography can say. People should say it’s their very own opinion, based on their experience with the visual tool that is photography. You can’t say ‘it’s Chechnya’, Cuba, or Afghanistan but ‘your view of Chechnya’, Cuba, or Afghanistan.

Going back to the Deutsche Börse photography prize, I have a cheeky question for you: do you reckon that having Joan Fontcuberta among the jurors was crucial to the nomination of your project? I mean, your project is ‘fontcubertian’ in a way…

I don’t know. I wish I knew. I remember when he informed me about being a finalist, and I said thank you, he was very direct: ‘no no Cristina, you don’t have to thank me’. He knew the project because I gave him the book in Arles. Also it’s an approach to photography that he appreciates I think, but I didn’t have the feeling that he was crucial to my nomination. It’s a very consistent and serious jury. Also, especially because my approach is similar, even if we come from different backgrounds, if I were him, and I see someone who does a sort of similar project, talking about the moon in an impossible way, and playing with facts and fiction and so on, I admit that I wouldn’t be comfortable with that. But maybe I am a woman, we are mean and not generous…let’s talk about clichés! Anyway, he is definitely one of my favourite photographers.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

Jörg Colberg, in his essay that accompanied your work in Foam, concludes that for the viewer The Afronauts ‘becomes completely believable as something that made perfect sense’, namely as something plausible. In an interview with Slideluck London for GUP magazine, on your Chinese project Made In, you said that you “re-design reality and filter it to make it more fantastic and unbelievable”. The sense of humour, I think, helps the viewer to suspend his disbelief. However, in another interview with The Telegraph you said you want your audience to react questioning if what they are seeing is true or not. It seems that you are also concerned, then, with what Todorw defined as hesitation in the reader towards the verisimilitude of the narrative, in his book The Fantastic. So do you want your audience to suspend their disbelief and enjoy the narrative or to hesitate?

I want the audience not to consume photography as it has been consumed so far. It has its codes, for example you can recognize an advertising image of a shampoo, you see a girl having a shower you know it’s about shampoo, then you see a picture of a very shiny car, and you understand that it’s about the car and its brand, you see two men shaking hands and you know that it’s about business. So we actually understand what the image is saying more than what it is really representing. With photojournalism it’s the same. We know that Africa is struggling every time we see a kid starving with flies around the mouth and that is the message: ‘So now on this page you have to feel pity for Africa; in the next page you want to desire and then buy the shampoo; and in the next page you want to travel to Seychelles…’. So they are actually directing your thoughts. And it’s this point where you see the image and immediately understand what it’s all about that I want to play on. I want to create images and I want to create stories that break this direct link, because for me it’s the only way to redefine photography, to push this re-education that I think is so necessary.

EMAHO : Could we say that you want the audience to become aware of the viewing process itself?

Yes, I want the audience to understand why the image is there and what it is telling them, other than ‘Oh it’s Seychelles, it’s beautiful, coconut and beaches’. The picture of Seychelles is there because someone wants you to spend your money and go there.

EMAHO : But then, do you think that without telling people in the interviews that what could superficially be seen as a book that makes fun of Africa’s underdevelopment and failure narrative, in a very patronizing way, is actually, on a subtler level, a book about our Western biased perception of Africa, the message would have been clearly understood?

I think so. For me part of the success of the book is not only the prizes and so on, but also the debate that it has generated. For example they invited me to speak at lectures and conferences that are not about photography, but like African future, and how we can give another image of Africa. It is very funny and I have started to realize that all these concerns of being very careful and making clear that you are not offending Africa, it’s something we just have in the Western world. When I show the book to people in Africa, they just laugh about it and they like it. It’s such a Western sense of guilt to always worry about stigmatizing the other. And what I tried with the book was to recreate the first impression I had when I learned about the story. I was like: ‘This cannot be true’ and then you see the images and the interviews and you realise it’s actually true, wow, and then you become fascinated about how incredible it is the whole story, and you smile. I was observing my own reaction. I already knew what I wanted to do with photography, I just needed to multiply and push the story to its most exaggerated limits. You can just rely on the surface of the story, and it’s still enjoyable. But for me the very fact that you don’t know if it’s true or not is in itself a big achievement. If you see a photograph and you don’t know if it’s true or not, that is huge. And that’s why, I think the book was successful, because people keep on asking me if it’s true or not, if I have ever been to Zambia. No I have never been to Zambia! Of course I am not going to change the media or the situation in Africa with a book, but maybe working on this different type of photography can possibly help later, in other ways. I don’t know.

EMAHO : As Pete Brook pointed out on Raw File, Wired, The Afronauts ‘is a serious challenge to audience viewing habits’. In particular, there is an image that quite strikingly subverts any logic: the photo of an implausible ‘alien’ on a hospital bed. How should we read it? Would the book be different without it?

I don’t think the book would change that much without it. For me there was also this game of how the images were made. It’s true that if I had to start The Afronauts without relying on my archive and invent everything, it would have been really hard for me to think about constructing an alien on a bed, it’s something that my imagination is not able to create. So what I did was to start from my archive and identify the images that could fit in the story and take them out of their original context. There is very little manipulation in the images of The Afronauts…maybe only in two images I added or removed something in a very subtle way. And without these images it will be boring, as these images open the interpretation. The alien is a photo I took in New Mexico in 2009 when I went to the alien museum and I took like a tourist picture. Then, going back to my archive, which took a lot of time, when I found it I thought it was perfect. If you think about the space there are big questions still open, the first one is: ‘are we alone in this universe?’ I was working on the clichés about the space. In the same way that I use the elephant talking about Africa, I needed to use the alien to talk about the space.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : Among the artists that inspired you, you often mention photographers like Duane Michaels. What about the fictional art par excellence: literature? I know you read lot… how does it inspire you? Who in particular and why?

Yes I read a lot, but it depends on when I read. For example in summer I just read novels and when I am on holiday, even if I can’t remember the last time I was on holiday, I normally choose easy stories. I also go a lot to the movies, at least twice per week, but it happens to me that I don’t enjoy the story because I am too focused on the structure of the book, on the skeleton of the story: ‘now there is a description of a place, now some action, now some introspection’. So at this point I am obsessed with storytelling and how you build dynamic stories, it’s very hard for me to enjoy just the surface of it or the same experience of reading. The books that I really love are those about the theory of psychology, I am very interested in how ideas are created and how memory works, through this amazing process of translating words or ideas into images. Also I love books that just play and mess with everything, like Cortázar’s Rayuela,Borges…They just use words as objects, as visual things, they play with words and play with the medium in a very creative way. They break the codes and I love that.

EMAHO : In an interview for a Spanish blog you said that The Afronauts was one of the most entertaining projects you have worked on and that it allowed you to recover memories from your youth, could you give us an example? Is there any autobiographical secret lurking behind The Afronauts?

I think the idea of space belongs to the collective childhood’s dreams, it’s not something specifically mine. It is true that when I was a kid we watched a lot of movies with my brother and sister, really bad quality movies, at the beginning of animation, like Jack the Giant. But I love these movies. Also we watched a lot of French comedies of the 1960s as my father has always been obsessed with Tintin and obviously in Tintin my favourite volume is the one about going to the moon…it was amazing, the sky, the stars, the rockets…I read it one thousand times! This is something that inspired me, because I had a very clear preview of the kind of images I wanted to make. So this is how I built the storyboard, I was really influenced by my childhood, my father just forced us to read Tintin and we became addicted to it! And then in terms of specific images, for example the one with the skull on the mountain, this is actually something that I have been seeing every day since I was eight, because it’s a mountain right behind the school where I used to go, the French Lycée in Alicante. And when I was looking for images that were real but enigmatic I just remembered it. You cannot create from nothing, you recreate and redefine things you have absorbed, you use your memory, your curiosity, things you never dared to answer and you just give them your own interpretation, filling gaps, and The Afronautswas something like that for me.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : The book was designed and edited by Colors magazine creative duo Ramon Pezzarini and Laia Abril, how was to work with them? Any magic moment that you recall?

It was amazing working with them, I learned a lot and I think without them the book would not have been that successful, by far. They were really good at translating what I had in mind. It was a very constructive working team. Now that I am doing other books I see how the relationship between the photographer and the designer is massively important. The magic of this team was that we all agreed on everything. It was just like playing and adding amazing layers to the project. It was different also because it was a self-published book and I had the last say on everything, so maybe that’s also why it was so easy for me. Maybe you should ask them if they enjoyed it. Now it’s different, there are other things involved like distribution and publication costs that a publisher has to be aware of. I didn’t have any expectations on The Afronauts. I was very lucky to find Laia and Ramon who understood perfectly what I wanted. You really need a designer who knows what kind of person you are and the message you want to communicate, so it obviously helps if you have a close relationship with the designer. The ideal is to work with professionals that share your philosophy.

But then that sounds like finding a husband kind of thing…

So it’s impossible then! (smiles).

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : What has been the main challenge for you in the adventure of turning a beautifully complex artistic book into an exhibition, avoiding the cliché of frames on the wall? Do you act as your own curator or are you open to ideas from the curators of the place where you exhibit?

So far I think I act as a curator, but not because I want to be a curator, just because I control the story more than anyone else. So far all the proposals I have made for the design of the exhibitions have been accepted almost without any change. I translated the book onto the wall in a way that I think is dynamic and that compensates for this lack of object. You have to experience the story virtually rather than touch it.

EMAHO : Will you include a copy of the book in the exhibition, or any props?

I didn’t want the book to be there, because especially if you cannot open it, it assumes this aura of a relic, as you won’t be able to touch it. In the end probably there will be one, I am not sure about it… I start to install tomorrow. I don’t think it’s necessary. I really worked hard to have the iPad app ready before the Deutsche Börse opening, so that people who really want to experience the book could do so, even if it’s not the same of course, it’s the closest I could get. It’s also going to be free to download on the day of the opening. I have always thought that part of the success of The Afronautsis the story itself not just the book. No props, it would be too much. I have everything, the flag, the rock and so on but then it becomes like a science museum exhibition, which is not the case with The Photographers Gallery. They asked me to do a special edition of a print from an image that is not in the series and I think that’s a very good idea.

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

© Cristina De Middel, from the series The Afronauts, all rights reserved

EMAHO : What was an exhibition that really fascinated you?

Taryn Simon’s exhibition ‘A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters’ at Tate Modern. I have been there three times. The story was extremely interesting and also the way it was presented, in a very coherent way: less is more. It’s really striking how this amazing story of family bloodlines was presented in a very aseptic way. Almost suggesting a kind of democracy, we are all the same. She has a very organised and clear mind and the exhibition reminded me a lot of the Periodic table of elements in Chemistry, where the elements of nature are reduced to something you could understand. I never understood the Periodic table, I was really bad at Chemistry, but it remained in my memory as something that contains everything in nature, and I think that’s amazing.

EMAHO : You seem to enjoy transmediality and multimedia: the photobook, the exhibitions, a video, the iPad edition, the performance in Milan during Salone del Mobile. Would you consider a movie about The Afronauts, and if so who would you like to be the director?

There is already a short movie by an African woman. I wouldn’t consider a movie now, because I think the story would lose its dreamlike nature. In a movie you need a beginning and an end, which the book doesn’t have. But if I had to do a movie, I think it would be David Lynch, definitely!

EMAHO : One last silly question, what would you tell Edward Makuka Nkoloso if you had the chance to meet him?

Would you marry me?

Photographs by Cristina De Middel

Photography Interviewed by Federica Chiocchetti

Federica Chiocchetti is a researcher of photography and literary theory at the University of Westminster in London and an independent curator. She is a contributing editor from Europe.