Bangladesh – Through rediscovering his own culture, Munem Wasif aims to raise awareness around the world with compelling images of his Bangladeshi homeland. His photography is deployed as an elaborate tool for storytelling; the intention of his work being to get viewers to gain an understanding and appreciate the smaller unnoticed fragments of life in his part of the world.

Wasif deals with issues that are very important within the Bangladeshi community, taking the right tone to deliver very honest work that communicates what life is really like – a compassionate and emotional experience for anyone who views his photographs.In this in-depth interview with EMAHO, Wasif tells us how his grounded roots in Bangladesh have compelled him to become one of the most promising documentary Bangladeshi photographers around.

Tell us about your first discoveries in photography.

Well, that’s a big question… I was never good at academic studies so I was always interested in something else. At first, I wanted to be a pilot and then I wanted to be a cricketer, but that didn’t work out because as a kid they’re just dreams and my father wasn’t really happy that I was showing an interest in this sort of thing.

My uncle was a student of geography; for his academic trips he got to go to so many different places, so he bought a camera and started taking pictures. At that time he had some kind of interest in art so he was listening to all kinds of classical music etcetera. He came back home with all these negatives and photographs, which were all around his room. As a teenager I was always interested in what he was doing.

When I finished school he saw that I was interested in that kind of thing, so he introduced me to a photography school called Begart (Institute of Photography). He asked me if I wanted to start a short course for one month to see if I was really interested or not. I think that introduction was really crucial. The school was the first school of photography in Bangladesh; the founder is Manzoor Alam Beg. He passed away; his son is running it now. The interesting part is that this place was not like a school. It was like a studio. This man was from the 1960s. He had at least 500 LPs, different kinds of books; it was a very different kind of life from I had been exposed to. I was more interested to go there and just hang out with him and see different magazines and books, so that’s how it started. I finished the course and bought this Russian camera that didn’t have a meter, and was pretty difficult to get an exposure with. So I was going here and there, trying to take some interesting black and white photographs, but it was really difficult. At that time, I had already seen the work of Raghu Rai so I wanted to take photographs like him.

Tomtom (horse cart) in Old Dhaka Street, Gulistan, 2003 © Munem Wasif

Tomtom (horse cart) in Old Dhaka Street, Gulistan, 2003 © Munem Wasif

What did you like about his photographs?

I think I liked the magic in his photographs, thousands of things happening at the same time; I think it really has a different kind of beauty in terms of life. It’s not about the positives and negatives, but there was a certain kind of spirit that I really connected to. At the time I really wasn’t an expert on photography, I was just beginning. Then the first Chobi Mela happened, I guess it was 1999 or 2000-and-something.

I saw in the poster there were a lot of workshops happening and a lot of foreign pictures. So I went to Pathshala. Before entering the gate I see the whole crowd. There were all these famous photographers and there were always foreigners. I was nervous and didn’t enter the school. I learnt that you can only participate if you are a student of Pathshala.

So I started to see the exhibitions at the National Museum. There was an exhibition by World Press Photo, a retrospective of maybe 20-25 years, all these historic famous images. It was a claustrophobic experience. There were so many good images but there were certain images, which really attracted me. There was a photographer called Roger Hutching – it was a photograph of a young couple who were holding each other and dancing in front of a old house and someone was holding the tape recorder behind. It had a very different kind of mood and I don’t know why but that image really left an impression on me.

Then I went to Drik and there was a huge, life-sized portrait of a very famous painter SM Sultan, a huge black and white portrait by Shahidul Alam. I should also tell you that before I had an interest in photography I already had friends who were painters and poets. I was going to Shahbag Art College, so I knew a little bit about the art scene. I felt that if I could manage to take a single photograph like this I would be more than happy in my life. The very next year I enrolled at Pathshala and then little by little it I started to learn.

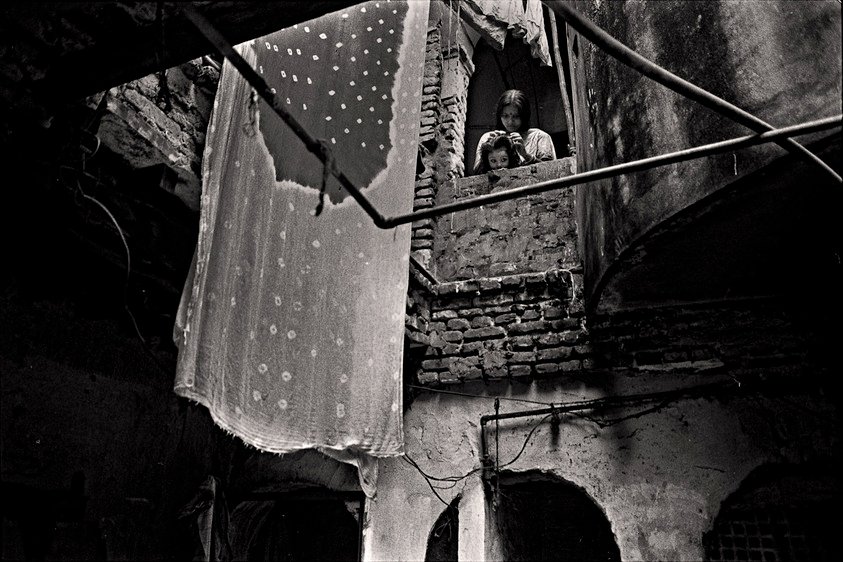

A mother cleaning lice from daughter’s hair, Panitola, 2004 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

A mother cleaning lice from daughter’s hair, Panitola, 2004 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

From that era to now, who are the photographers that have inspired you?

It’s difficult for me to answer because I have learnt to look at photographers’ works that are extremely different from me. In the beginning I would look at different bodies of works, some I liked some I didn’t, but now because I also teach I have got introduced to the history of photography. In one sense, I have a more refined eye; on the other hand, I am more corrupted. I can enjoy so many different kinds of work. If I give you my list it would be difficult for you to understand what is my taste.

I am really curious to know about the naïve and innocent approach you had towards photography in the beginning of your career. So if you can just talk about it briefly.

In the beginning I will say I was more into the Magnum kind of photography where it was very humanistic and there was a certain kind of moment in there. If I were to say who my favourite is today, it would be Graciela Iturbide . I love the poetry she has in her photographs but if you compare her work to Raghu Rai, there is no moment but there is some magic. To be more specific I really like works that have a very strong emotional grounding, that really push you to somewhere else. I want to be moved by pictures. I can read intellectual photography, which talks about something else, but that is not really my palette. I still want to be in a more intuitive zone but I guess with a little bit more political and social understanding. It’s not only about aesthetics.

If I’m not wrong, she was also at the last edition of Chobi right?

Yeah, we managed to bring her here.

Pintu and his friend having first tea of the day, Panitola, 2004 ©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Pintu and his friend having first tea of the day, Panitola, 2004 ©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Which is great. Along with this you’ve mentioned in the past that there is importance in documenting your own life and that photographing your own country holds a truth and more of a personal story. You have been able to work on some really important and strong subjects, so what is the significance of thinking locally to you?

I will not term it thinking locally. If you look at all the famous filmmakers, painters and writers from Bengal, they have all written in Bengali. They work in their country. I think photography is one of the few professions by default where you can travel to different places and explore and photograph community stories that you aren’t familiar with.

As someone who comes from Bangladesh, I know we don’t really travel a lot. The economy is different, it is expensive for us to travel. It’s not like in summer we go to Tuscany and have a holiday then come back to Dhaka. I have never thought I need to go to Uganda and photograph something so I think it comes naturally in one sense.

On the other hand, it’s also very difficult for me to travel somewhere and work for 2 weeks and come back; I don’t understand how people do it. I think the people who do it are really smart and it’s great. I’m a shy person; it would take me a long time to get really connected to the subject I wanted to photograph; normally my projects are for 2,3,4,5,6 or even 7 years. The last work I’ve done on Old Dhaka is now in almost its 11th year. So you can imagine that it’s not possible for me to go somewhere else and work for 11 years; I have to be there and have easy access.

The language is also important because it’s important for me that I talk with the people I photograph; I don’t want to photograph a stranger; I just don’t want to go somewhere and take a photograph and come back. I want to enjoy the whole process. So working in my own country becomes extremely important; we have so many interesting things in our country. You look left and you look right, you have endless stories. I don’t need to travel to different places to produce my own work. I decided I wouldn’t be a magazine photographer and I will not work like a typical photojournalist, so I have dealt with the issue in my own way.

Daily life in a courtyard, Panitola, 2004 ©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Daily life in a courtyard, Panitola, 2004 ©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Lately, there have been a lot of debates about how photographers from this part of the world are trying to imitate a lot of the work that has already been done in the past. On the contrary, what you have produced is your own niche with your honest approach towards some really important issues in Bangladesh. How do you think this whole mind-set can be changed?

When people ask what is exactly Bangladeshi or Indian photography I think it’s very difficult to describe…

I understand. I think there’s a lot of pressure to prove yourself and to be established in the profession. Of course, you need to be inspired by good work, no matter where it is from. Sadly, if you want to publish your work most of the places are in the West. The award grants are mostly from Western institutions and the history of photography we have seen is also very Western.

When younger photographers look at what they need to do or what they like, I think that has a role. When I first went to Tokyo I looked at books by Takuma Nakahira and Daido Moriyama etc. Long before that I had been to Europe so I really liked the work of Anders Petersen. When I look at Daido’s work – who has done this for a long time and I look at his book – I get the sense that Anders Petersen is technically influenced by this guy but nobody talks about how a Western photographer was influenced by a Japanese photographer. But then I guess Daido maybe was influenced by William Klein.

You used the word imitate, right? I think people get inspired by a lot of different things, so for me that’s not a problem until you start copying someone else’s work – that becomes childish, but that’s a different story. For me, getting influenced by someone, that’s not a big problem, I think you will get your own language little by little if you are really honest with yourself.

You just mentioned how the publications and organisations that support photography, and take it seriously, are in the West. But don’t you think there are organisations from Asia who are trying to build that space? Lately, there has been a lot of activity in Asia itself.

Yeah, I think a lot of things have started but if you look at it in terms of history and scale we are nowhere. If I talk from my position, I work in Bangladesh, there is no magazine, which can publish your work or pay you. There’s no gallery, no museums. I think in India it has started but not in a lot of countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Burma and Pakistan. Excepting the US and Europe and maybe a few exceptions in Asia, photography is concentrated only in certain parts of the world.

I will give you an example. There are certain stories, which can be really important for us here in Bangladesh and India. I once proposed this story to a Western magazine and they had to publish it internationally. Bangladesh is just a small country, one of several hundred, so maybe some stories are internationally not important. What then happens is we only introduce stories that will be interesting for that audience; for me that’s a big problem. We really are limited to stories that people are interested in in the West.

An old woman combing hair, Shakhari bazar, 2008©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

An old woman combing hair, Shakhari bazar, 2008©Munem Wasif/Agency VU

In my recent interview with Simon Baker of Tate Modern, he said that Europe is no longer the home of photography and many other curators have agreed to it. Having seen a lot of activity recently in Asian photo-world, what do you think of the same?

I think a lot of things are changing, but I’ll also tell you that you are asking this question to curators from somewhere else. If you asked this question to a curator in India maybe they would give you a different answer. We have to think about who is looking at what, who is discovering whom? You know? We are always being discovered by someone else.

My point was that in terms of creating opportunities for young photographers.

In my case it was different because we had Shahidul (Alam) who looked at new photographers’ work, pushing them and introducing them to different places. I’m sure in India the case is different.

Goddess Durga just before immersing into Buriganga, Swarighat, 2009 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Goddess Durga just before immersing into Buriganga, Swarighat, 2009 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Now coming back to your personal life as a photographer, I was listening to your artist talk during the Delhi Photo Festival where you talk about how you got into Agence VU. Could you share your experience of working for them; how has it been?

I think I was really lucky that VU took me for their list; I think I have a lot of limitations. First, I only work in Bangladesh; secondly, I work only in black and white, mostly, except some commercial work; and thirdly, I am very concentrated on what I want to do. So from their perspective I’m really difficult to sell, so I will not complain that they don’t sell much but, on the other hand, they are also very French – that has also something to do with selling.

I think joining VU was for me very important in a different sense, because if you look at the list of photographers they have, it’s extraordinary, it’s crazy. There are very few ‘agencies’ in the world which have such an interesting variety in their list. There are a lot of photographers who don’t fit anywhere. You look at a lot of photographers with Magnum, people like Antoine (D’Agata) and Cristina Garcia Rodero. A lot of different kinds of people, they were all in the VU including Paolo Pellegrin or people like Philip Blenkinsop.

I was not really motivated to go to Pakistan, or go to Cairo or different places and produce reportage. I was mostly doing my own work and luckily VU doesn’t have a problem with that.

Then you know I also got involved with teaching so I started to teach at Pathshala, I have been teaching there for the last 3 years…that takes up a lot of time.

I was also trying to help the younger photographers to try and break the prototype we have in Bangladesh and push them a little to produce a different kind of work, which took a long time.

Bath in Buriganga, Babubazar, 2008 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Bath in Buriganga, Babubazar, 2008 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Then we also realised we don’t have any history of photography in Bangladesh, we don’t have any text in Bengali, so my friend Tanzim and I we started to publish the book ‘Kamra’. We took interviews of all the important masters in Bangladesh. Through that we thought at least orally we would have some kind of history so later even if a researcher or anyone else wanted to write about the history of photography in Bangladesh they would have references.

We also translated the important texts from English to Bengali so the people who want to read, but don’t have enough skill in English, can also get access to important texts. I have done a lot of different kind of things; I was involved with Chobi Mela as a curator – that also took a bit of time and energy.

For me, I really enjoy everything about photography rather than just being a photographer. Taking pictures is just one process but I think working with pictures, reading, looking at different bodies of work, teaching, travelling and curating – I really enjoy the broader spectrum of it. I have learnt more as a viewer in the last few years or as a reader of photography than what I have learnt as a photographer. When you’re looking at photography from a photographer’s perspective a lot of the time I think it’s very limited because it depends on what kind of work you like. I manage to really challenge myself and I think I have travelled to different spaces in photography, yeah, so that’s it.

You mentioned that the Agency is really French and I remember when we were on our bicycle ride coming back from Anjali House in Cambodia, and you had mentioned this one thing, you’d said that the French actually know how to celebrate photography. Do you think something of that sort is expected in Asia and can lead to those standards?

Ummm, I think certainly. If you look at the festivals, especially in France, I think they were doing it for such a long time that they really needed to discover new work. You can imagine that after the 5th edition of the Delhi Photo Festival I guess they would have exhibited all the people they have known. So they really need to find new and fresh work and push themselves and give themselves new character. I think people will also start to do it here, but I also think in France they are really interested in discovering new work from different parts of the world. They really respect photographic history; they have a space for photography in a lot of different spaces. I guess US is the place in terms of market and money but I don’t understand why the two best festivals in the world are in France [laughs]. Why aren’t they somewhere else? For me that’s a really big question, I don’t know why!

Bimol da preparing fish for cooking, Beauty Boarding, Bangla bazar, 2011 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Bimol da preparing fish for cooking, Beauty Boarding, Bangla bazar, 2011 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

It’s true, I suppose the French take photography really seriously in terms of investing money, supporting it, getting people together and discovering new talent. I was talking to Françoise Hebel and he said for us it’s not the 110 exhibitions that we curate but also that we collaborate and get curators on board so everybody works as a whole team.

Manik, I think one thing we need to act on is that most festivals are also supported by the city. I think the government needs to be interested in promoting art and support these kinds of festivals. You look at the initiatives in Asia – they’re mostly from private organisations and mostly from people who really love photography, so I think here the whole mechanism is different.

I completely agree; the whole mentality needs to change. Recently I turned to ICCR (Indian Council for Cultural Relations) because there was a very interesting project related to photography and I just got a one-sentence reply saying that ‘photography is not our mandate’ and ICCR is the cultural organisation for the government of India.

Yeah.

Coming back to your Old Dhaka work, if I’m not wrong you started shooting this work almost 11 years back, right?

Yes, that’s about when I started.

How did you think of shooting Old Dhaka out of any other places and how was the first experience?

When I moved to Dhaka, my mother passed after a few years of my being there. I was young and was just starting to learn photography, and little by little I was discovering myself. I was brought up in a small town called Comilla, which is like 2 hours from Dhaka. It was a different kind of place compared to Dhaka because we had all these colonial British buildings and the neighbourhood feeling was very strong. The same thing happens in any small town in our part of the world.

When I moved to Dhaka it was a little bit difficult for me to adjust but Old Dhaka was a place where it felt like my small town. I felt it was more human, people really talked with each other and I think photographically it is fascinating. It’s like theatre. It is something similar to what you feel when you go to old Delhi and maybe old Calcutta. These small old towns have very rich traditions in terms of food, culture, music; the architecture is beautiful.

To be very honest, it was extremely exotic for me. I started working in a narrow street called Skakhari Bazar, which is a Hindu street, where I guess more than 40,000 people are living. Things were happening all the time, even at night, so as a young photographer there were a lot of interesting things to photograph. I don’t know if you have seen ‘Cinema Paradiso’ by Bertolucci… it’s like when a young kid starts to ride a bicycle and when he wants to get lost in the city and discovers new streets, new people, new places, it was something like that.

You have said that you relate to the little moments you see in Old Dhaka and that they remind you of your childhood. As a documentarian you focus on the smaller nuggets of life in Bangladesh. What is so significant to you about appreciating the details some may take for granted?

I wasn’t really working as a documentary photographer, I was just walking around and photographing things I really liked. I was really touched by these unique characters of Old Dhaka. There could be a little guy who maybe sells perfume in the street or the little vendors or these beautiful old houses and this feeling of a neighbourhood.

I was not really trying to do something big, I liked the space, I love to be there. At the time I was really into street photography so I just walked around and photographed the small moments, some of the things I think subconsciously were rooted in my childhood. It was almost like a nostalgic feeling and I was more into just going around and looking for these magical moments.

Did you ever encounter hostility when you were pursuing your projects?

Not really. Many times, when you go to people’s house, some would say don’t take photographs. But when you have been in a place for 10 years, you have friends there. I go to certain places to eat and a lot of the time I don’t take pictures. I just go there and hang out with people, talk for a few hours, then I take pictures for half an hour or something, sometimes it works sometimes it doesn’t. After some time I started to live in that part of the town so I lived there for 3 or 4 years and then in the last 2—3 years I stayed in a boarding there for like for a week. I have a lot of different kinds of connection with that part of the town.

After all of the years spent there, what lead you to the book you are producing now?

I’m really into books. I think it’s really precious in photography; it’s one of those special things. Also, I wanted to give the project shape in the form of a book because I wanted to see the work being somewhere for a long time. I’m sure when people look at this work after 25 years, it will feel strange because the Old Dhaka is changing so rapidly and people are breaking all these old buildings, and the architecture, characters and lifestyles are changing so fast. I was looking for a publisher, then I found someone who was interested, that’s how the book is out this September.

Is this an on-going project or is this an end to the project?

I think I will still take pictures there.

You are also exhibiting the same work this coming October in France?

Yes, there will be a small exhibition in Paris with the book launching and I will also exhibit this work in Phnom Penh at the Photo Festival. I’m planning to do an exhibition in Dhaka, but I need to make some plans around how I will get funds and other things.

Do you find exhibitions and festivals a successful way of getting your work out to a wider audience that might have never heard of you or do you believe producing a photo-book is the best way to display your work?

I think they both have different kinds of levels, they are both very different from each other. Exhibiting at a festival is beautiful because you also get to meet a lot of different kinds of people there, you also get to see a lot of good work, a lot of people who have never heard of you come to one place to meet you and look at your work, so I think that’s wonderful.

For me, the book is something really different; it has a very different kind of form. It’s an object you can hold; you can keep it in your home for years and you can look back through it. The narrative is different, the texture is different, the smell is different – so I think both forms have their own character.

I am really happy that my work is getting published but now the problem is how will I get my books in Bangladesh. They will become so expensive to sell here. I want my books to be sold in my own country so the people who really admire my work in Bangladesh at least get to see it. Currently, I’m struggling to figure out the logistics of getting my book in Dhaka.

How is the local photo book-publishing scene in Dhaka?

I think we don’t have one. People still don’t understand the difference between a catalogue, a coffee table book and a real book. So I think it will take a long time to have that kind of thing.

Even though the photography done in Bangladesh is very well respected across the whole globe?

Yeah, people don’t really get to see photo books; we have just had a photo book show at Pathshala for World Photography day where we display 50 interesting books. We’ve only started to expose this form of display to the public now. You need to understand that it has a lot of things to do with the industry; you need money to publish the books, a reader who will appreciate it and who will buy it, and then you also need to have a printing industry which has the technology to publish these books in a cheap way because now people can publish cheap books in China. We are still in the analogue times in my country in terms of printing. We don’t have digital machines, and to publish really good photo books, you know it’s quite expensive.

You were formerly educated and currently teach at Pathshala, and you’re also hosting a workshop at the Delhi Photo Festival 2013. Can you tell us more about your teaching philosophy and what your role is as an educator?

It sounds heavy to see myself as the educator. I don’t see myself as an educator, what I do is I really love photography and I try to share my passion with other people. I love to look at different bodies of work. I try to read it and travel within the pictures so I share my stories. I try to open up as many windows as possible, I tell them it’s not about Munem Wasif. I do not show my work to my students at all. I want them to be themselves so I try to build a space and environment where I show photographers’ work that are really challenging to each other.

I show the work of a photographer like Cartier-Bresson, about the decisive moment and spontaneity next to someone else, let’s say Robert Frank, or Gray Winogrand, who has a different take on street photography. So the students will see the difference in photography and that nothing is ‘best’. You can learn from a lot of different spaces, that is one thing I am trying to do. I found that the photography situation in Bangladesh seemed to be people who were all producing similar kinds of work. It was getting quite repetitive. We strongly felt that there are several other things people can do – we needed to expose those opportunities and windows in front of them.

Coming from a teacher’s perspective, I would like to know how good or bad it is for a student to get inspired/influenced by their mentor?

I think there’s a difference. I’ve taught in a school environment for at least 3-4 years, so I have to include a little bit of a lot of different things.

But have you faced that situation?

Let me explain. For me, Antoine is an artist. What he does in the workshops is share his experience; that students that go to the workshop to copy Antoine is their problem in one sense. I will not say problem, I think it’s that mind-set that they have. Antoine is one of the most open artists I have seen in my life. He is so extreme in his own work but when he teaches, he talks about something else. I think as a teacher he is quite democratic and extremely brilliant at pushing students to find their own voices and own languages but at the same time he still remains Antoine. He is such a strong character. I think if you don’t have a bit of strong personality or some knowledge in photography it is very easy to get influenced by others.

A band party in a wedding, Shakhari bazar, 2006 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

A band party in a wedding, Shakhari bazar, 2006 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Have you ever felt like some of your students are getting really inspired by you?

I hope they start to love photography like mad after my class! I show works of photographers in my class that I really hate [laughs] and I try to tell them why they’re so important. So for my students, it’s difficult for them to understand what I am really like and who I am.

Why?

I think it’s not about me. I just need to share my ideas and spirit with them. It’s not about Munem Wasif; it’s about them and what they want to do. I try to show them what will help them and what will challenge them and push them to a different level. On the other hand it’s very obvious that they also get a little bit influenced by me but I’m really careful about that. I don’t want to put my ego on the table and say – you know this is the best.

In terms of your black and white work, in one of your old interviews you’ve quoted describing people’s perception of Islamic culture to be “…black and white, and there are no shades of grey”. To some extent, does this ideology reflect the visual style of your photographs?

What I tried to do in that story was that I tried to bring as many voices as possible. I was trying to show that even in Bangladesh Islam has so many different layers. It’s such a difficult story to share and to photograph and I’m still struggling. I guess after 5 years I will give it a proper shape.

I’m still researching, taking interviews, looking at other people’s work who have photographed Islam or Islamic culture. I will start photographing maybe a little bit later. At the moment I’m really bored with my work so I am trying to do something very different.

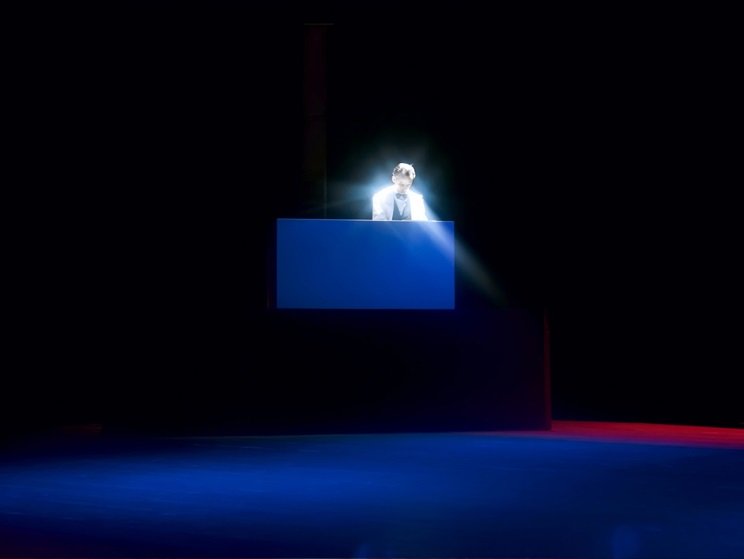

Morning film show, Manoshi Cinema Hall, Bongshal, 2009 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Morning film show, Manoshi Cinema Hall, Bongshal, 2009 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

Which is?

You will see when I publish the work. It’s in progress.

When can we expect it?

I don’t know. I will tell you a little of what I’m doing is taking stage portraits of the people I really like in my generation, so it’s more like a fictional story, nothing to do with the street, nothing to do with documentary photography.

Are these people also a part of your life?

They’re my friends, they’re artists. I am photographing people who are close to me, who have influenced me in different ways and who are really important to my generation in Dhaka.

I also want to publish a photo book in Bangladesh in Bengali and yeah so I’m thinking I will start working soon on that.

In one of my interviews with Shahidul, when I asked a question to him about the emerging generation of photographers from South Asia, he replied referring to Sohrab and you, “I think Sohrab and Wasif have taken a bigger role; one of the mistakes that we have made both in the photographic role and our approach to photography is suggesting or implying that just taking a photo is what photography is all about but I guess photography is a bigger animal than this”. Have you been bitten by this animal yet?

I was bitten by Sohrab and Shahidul [laughs], they are always kicking my ass. I think they’re really intelligent people. They are great human beings and I love them both. I don’t know if they’re animals, but I was really bitten by them a lot of times. A lot of times they have asked me such difficult questions that I have to start thinking from scratch. But, on the other hand, Sohrab and me are really different people. I really respect him; I think he is one of the most intelligent people I have seen in our part of the world, and he is producing amazing work, but I think we are very, very different. We have different likings and different niches and we want to do different things but we share thoughts.

A young actor posing in front camera, rose garden, Narinda, 2006 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

A young actor posing in front camera, rose garden, Narinda, 2006 © Munem Wasif/Agency VU

What do you have to say about photographers having a bigger role?

I think that’s not very good. That’s killing our own work, that’s quite boring also. I just want to go to a street. I want to travel all over Bangladesh and produce beautiful pictures. This whole notion of educating others is quite boring and I don’t enjoy it much so I’m going to try and take a break from teaching after this year, maybe if I can manage to convince people in Pathshala.

That’s a huge decision…

I think it’s the same with Shahidul. He has really taken on the bigger role – he wanted to change the landscape of photography in Bangladesh. I think regarding me I don’t have that intention and I also don’t want to be someone like him, I really want to be a photographer. I want to share the things I have learnt in my life, and I want to share the things I don’t like. I want to raise different questions and have a really interesting community within myself. I don’t want to fool around and think I am the best photographer. I also want to be challenged.

Photography Interviewed by Manik Katyal