U.S.A. –

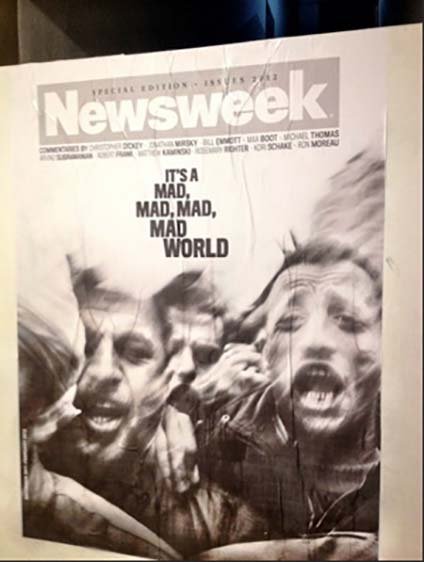

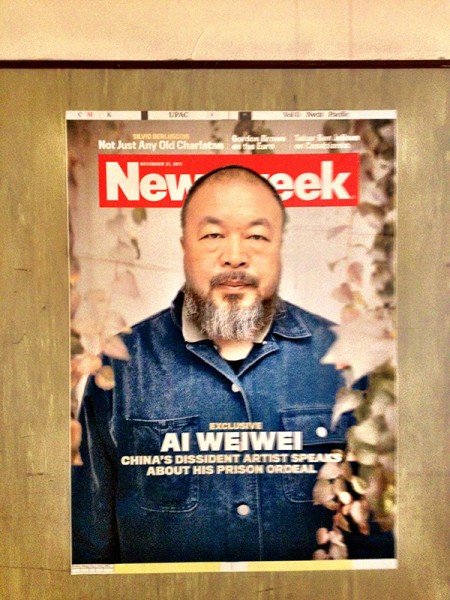

As part of Emaho’s media partnership with Cortona On the Move – Photography in Travel (until September 29th, 2013), I was there for the opening weekend to check out the exhibitions and events and to interview James Wellford, former Newsweek Senior Photo Editor and curator, together with Marion Durand, of the exhibition Newsweek : an Autopsy.

Now in its third edition, Cortona On the Move is a very promising photography festival in Tuscany, Italy, impeccably directed by Arianna Rinaldo and her fantastic team: ideal location and season; intriguing exhibition venues and a rich entertaining program of events, including delicious group dinners en plein air, perfect occasions for networking, one of the must-do activities when visiting a photo festival. Besides the Newsweek show, to which this article is dedicated, my highlights from Cortona are Joel Mayerowitz’s retrospective ‘Taking My Time’; Zed Nelson ‘Love me’; and Christian Lutz’s ‘Trilogy’.

It was a pleasure to interview James Wellford of ‘Under the Tuscan Sun’ fame, accompanied by the ubiquitous glass of red wine.

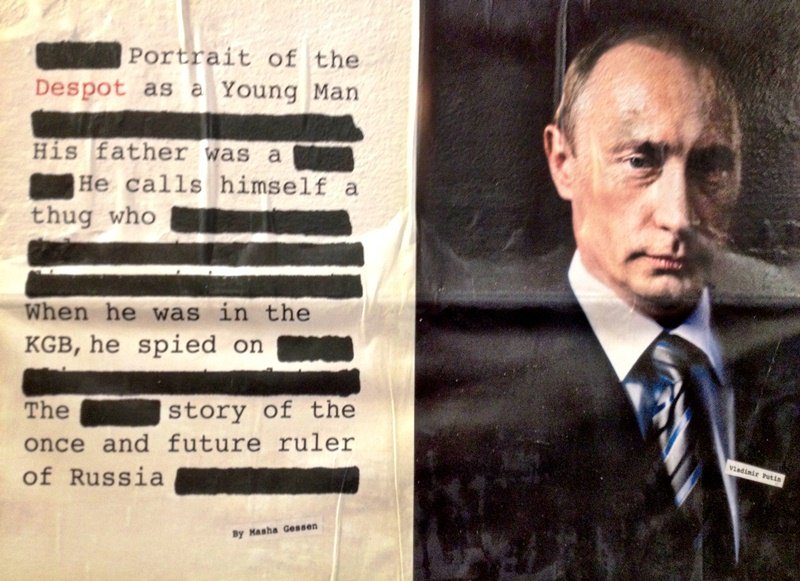

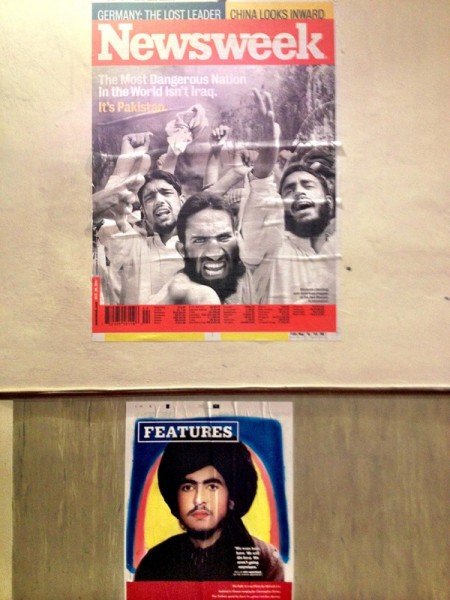

Let’s start from the beginning i.e. the title of your exhibition, ‘Newsweek: an Autopsy’. The word ‘Autopsy’ means the examination of a cadaver to determine or confirm the cause of death. The intro panel reads ‘Newsweek as it was produced in New York City for 80 years stopped printing in December 2012.’ The digital future of the magazine remains obscure’. However, the exhibition seems more concerned with the celebration of the visual achievements of the magazine rather than with the examination of the causes of its printed death. Could you tell us what happened and what could have been done differently to save the printed edition of the magazine?

I have to begin by giving tribute to Marion Durand, the co-curator of the exhibition; she came up with the title ‘An Autopsy’, which I should say many people baulked at it, they didn’t like it, but I fell in love with it completely, because it condenses the many harmonies and disharmonies in the magazine. Part of it is the splendid celebration of supporting visual storytelling and language at a particular stage. Much of what happened, in terms of politics and even the dialectics of an office, is a painful experience; there’s a lot of compromise. Much of my best work did not see the light of day in the magazine. But when I reflect on my 12 years there I still have to celebrate the handful of images, which were produced over the course of that period. But let me point one thing out to you, this picture of Obama made by the then contract photographer, Ilkka Uimonen, was never published by Newsweek, was never published in the States at all, it has never been seen. I had to come all the way to Cortona 7 years later to find a group of people who would publish that. It’s a strange satisfaction. I have harboured interest in this picture, among others, for years and years, because for me it’s genius. But photography is subjective; some people to whom it was sent said: ‘It works, but can you send us the one in focus?’

DMZ Boston MA, Then Senator Barack Obama, in his first campaign appearance. Now the president. © Ilkka Uimone for Newsweek

When was it shot?

I think it’s probably the first campaign. I intentionally left out a lot of dates of the pictures in the exhibition.

So has the magazine stopped printing mainly because of financial difficulties?

You know in the States it’s all very complicated. It’s not just me agitated by the end of that magazine, but people on the writer side, people on the copyrighting side, we all experienced this severe downturn in advertising. It’s a marriage with the devil in the United States. You support your magazine, which costs virtually nothing for a year’s subscription. At some level it’s a deal with the devil, for when the advertising dollars are no longer there, then the ability of the magazine to produce pages and pursue stories and support writers and photographers goes down the drain and across-the-board too. It must also be happening in Italy and England. For news magazines and particularly weekly magazines – what with social media and other online options – the original equation has essentially been destroyed. Some are still holding on and supporting work but it’s increasingly difficult when advertisers are not putting their money in anymore.

There’s a lot of responsibility on the editors and the people who run that magazine, to engage the advertising world and essentially say: ‘Look, you’ll feel better about what you do if you support an organisation like this that, at least in one aspect, is trying to engage with and tell the story of the world as we live it’. Certainly, under the direction of Tina Brown, initially there was hope. Her rise coincided with the Arab Spring and the disaster in Japan, so we tried hard for two and half months to put photographers on the field, had writers there. News stories aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, even though it happens to be what Newsweek did traditionally.

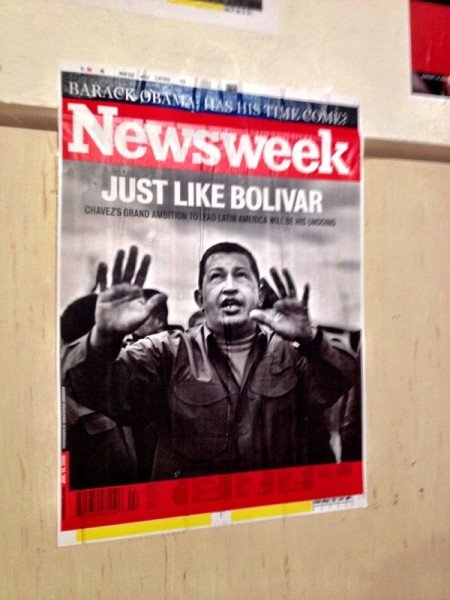

It’s difficult to change the entire attitude and personality of a magazine, even if you want to cover more pop culture and do tabloid-style journalism, especially when the title of the magazine is Newsweek! And I am not saying ‘News-weak’ with an ‘a’. Under that leadership and those compromises – and I am sure it’s complicated to try to get enough money in – Newsweek became so weak. Its personality dwindled; we no longer looked at original reporting in the field as something commensurate with what the magazine was about. The management backed off; they gave all the money to high profile writers, abolished all the contract photographers, names, personalities and creativity. Certainly, in the world of journalism, photography took a back seat to some of the more infamous portrait photographers who shoot celebrities and power. They still get paid. But it was depressing for me as I am interested in news. It was possible for me to take one assignment for a portrait photographer, then cut it in four ways. This would enable me to support stories in other parts of the world very easily. I always believed in that and I could not ever accept or understand why they simply rejected it, hook, line and sinker. In the end it was terribly disappointing.

And mysteriously enough they are still printing the international editions; I saw one in London… who is behind that?

It’s true, even I don’t know. The way it worked out in the flagship edition, which traditionally was always produced in New York, was that they eventually developed relationships with people to produce an English-language edition and foreign language editions; there is a Japan edition, a Russian edition, Mexico has an edition… But if you look at the international edition it’s really just a pamphlet. Someone made a deal, picked up the writing, then hired someone to photo edit it, but the photographs that you see in those editions – I saw one in Denmark – are all Getty, they are all wire. They don’t support individuals who are deeply associated with the magazine and help create a style, a shape, a form and a personality.

I never thought that they were going to continue with the international editions; it must have been a business deal done purely because Newsweek, at some level, still has a recognizable identity, so you sell that identity and cut deals. For years, the international edition was produced out of Newsweek, and many of the layouts that you see on the walls of the exhibition here in Cortona only ever appeared in the international editions, but the editors for the international editions were all based in New York. So it’s a pamphlet now, compared to what it was, just wires – the cheapest possible way to get pictures. And don’t get me wrong, I use wires all the time – I always have – and I know a lot of people who shoot for the wires and cover what’s happening around the world. But when wires become a way of cutting cost and saving money, and you never support individuals to engage with photography, it changes fundamentally the nature of the enterprise.

And what’s next for Newsweek? Why do you say that it’s digital future is obscure?

Tina Brown and the others celebrated the fact that they were going to save the magazine and the genuine creative core of Newsweek. They said: Paper is too expensive, a waste of money, we can no longer afford it, but our solution is to be ultra forward thinking and to go exclusively digital. We are going to call it Newsweek Global‘. Now, I get all that and maybe that is the future, but it seems like the paper is in real dire straits right now. Within months the direction of Global seemed to become fractured; the new entity looked underdeveloped. The owner of Newsweek and Daily Beast, Barry Diller, described buying Newsweek as the worst mistake he ever made in his life.

So when I say it’s obscure, I say it because at some level I devoted a lot of time to Newsweek and I don’t think that the people there right now have a strategy; they might have a strategy of course, but it’s not about Newsweek. They don’t really care about it. They are using it to bolster The Daily Beast. The idea was to marry The Daily Beast with Newsweek. But their real game plan, the way it appears to me, was to use Brand Newsweek’s name and reputation as an old school, hard-hitting investigative news organisation, to bolster the interests of the up and coming The Daily Beast, and to make it appear more serious and credible. During the period that I was there every single person who had been associated with Newsweek, was, one after the other, replaced by new people who had had no previous experience with Newsweek. These were people who had no idea of who the photographers were. This when Newsweek employed the best master contract photographers in the world. I can’t think of another organisation that can come close to what we had.

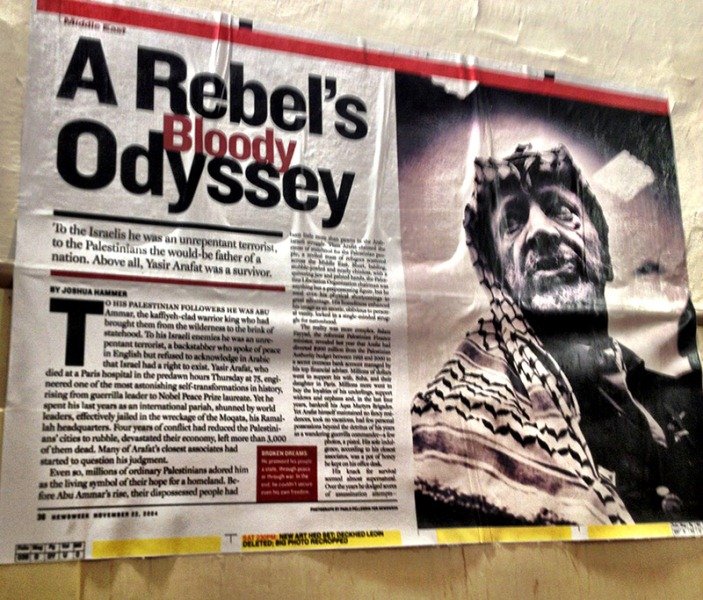

Could you give us some examples of masters that you commissioned? And what about the text that accompanied the photo essays?

Luc Delahaye, Alex Majoli in Iraq, as well as Paolo Pellegrin and Jonathan Torgovnik in Africa. They were commissioned all the time, not just internationally but also domestically – we used them to cover political campaigns. We also proudly worked with young unknown photographers, and Newsweek produced a lot of their works before they became known.

In terms of text, when you work as a photo editor you have to be thorough with captions, know the value of truth and integrity. I believe that in Europe it’s a bit more relaxed and you can be not so accurate. Well, at Newsweek that was never the case. Copywriters would call us late at night for clarifications and confirmations. We simply could not get it wrong. If we did we were fucked, that was the level of faith.

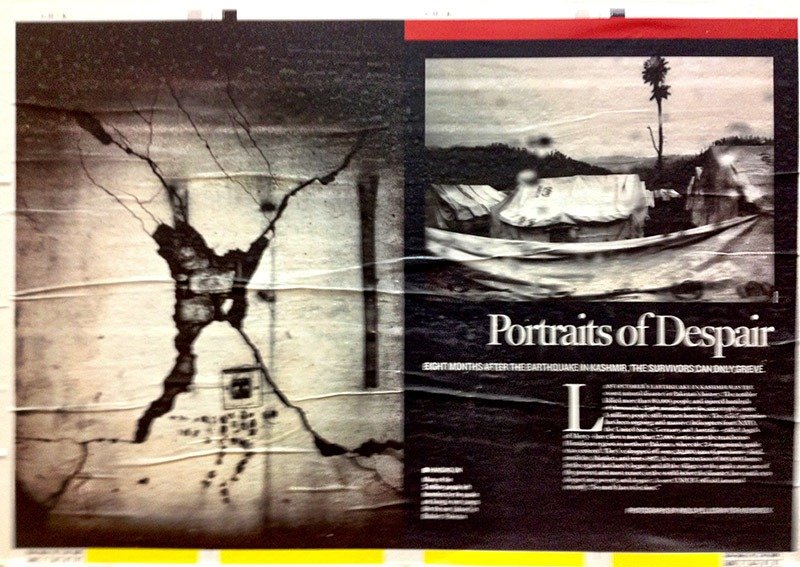

How did this exhibition project for Cortona On the Move start? And how did you and Marion work on it, in terms of the choice of the themes: Power, Conflict, Disaster and Struggle?

I am still trying to figure that out, because I was a little bit reluctant to do this project. I have been pulling away from Newsweek and it’s such a different place right now, I did not want to call out and claim it as a place that is in anyway what it used to be like, but then I reflected on its past, and there were a lot of powerful moments that deserved to be shared. The titles are Marion’s ideas; I let her move in that direction, after all it is a collaborative effort. The process of putting together the pictures – I wouldn’t describe it as the most organised moment in my life. It’s a combination of things that I have in my collection – covers, spreads; and, of course, it only represents a small portion of 12 years of production. We got together and selected a handful of different layouts that we thought representative, attempting to do something that worked both visually, both in terms of story, and design. Because we could have gone in many directions, we could even have juxtaposed it with awful design, a sort of destructive approach. I often do that when I speak – I sometimes juxtapose domestic magazine covers with international ones, just to see how far out thinking can get.

Could you tell us more about the eclectic installation, which combines blown up covers, spreads, single photographs glued to the wall and framed prints. What is the reaction you wish to provoke in the visitor, if any?

I am interested in politics and wall art. An exhibition gets tiring for me if it’s very formal, completely white walls, framed pictures, 90 degrees angles. I kind of like to break the 90 degrees angle. For example, the surfaces in that hospital were conducive, the hospital makes the exhibition be what it is, which I did not know until I arrived. We had a bunch of printouts, then we looked at the walls and sketched it out. We did a bit of that in New York too. Arianna, who invited us to do the exhibition, sent us pictures of the space. My metric calculation sucks, so we used Marion’s flat in Williamsburg to make some creative attempts, and it was a lot of fun as we are friends. In terms of creativity, most of it was driven by news and things that could be upsetting to people, because it’s a vile world and I am interested in that historically. It is very important for people to be aware of upsetting stories.

Do you think it suggests a reflection on hierarchy in the realm of photographic news? ‘The most political decision you make is where you direct people’s eyes’, said Wim Wenders in ‘The Act of Seeing’. The passage is quoted by Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin’s essay ‘Unconcerned but not indifferent’ .

I absolutely do. But I think that Adam & Oli and Wim Wenders are busier directing what they want to see. Their sense of the need to control is quite different to mine. I am an editor who says: ‘This the story, this is what I know about it, these are the logistics. I need you to see it and produce it for me, then we can go back and forth and talk about the central material that I want from your shoot there, but beyond that I also want you to be creative; the reason I am talking to you is because I want you to see it and explore it and turn us on, I want some mystery’. Obviously, that’s based on the faculties and sensitivities of the photographer, but I tend to believe in what they see and bring to my attention and then the commentary starts from there. I do not tell them the way I want to see a story, like ‘You have to shoot it in the afternoon so the lights are beautiful’. I want their creativity to be free to explore and to unravel the situation, because a lot of these things are not that easy to access. Much of what you see photographically in terms of hard news is really the journey to find where the story is. A lot of great pictures are made on the way, and that is very uncomfortable to people. For example, with Adam & Oli – they often neglect the journey of getting there. They have done work on suggesting an answer, and I don’t actually believe in the answer, I believe in the question. I want there to be some mystery in the making of the work, I want it to have certain unknown things going on when the works are transmitted to me. I am curious about that chemical moment, without controlling the photographers.

What do you think about the work of Alfredo Jaar – ‘Untitled (Newsweek)‘. How do you explain the lack of coverage in your magazine of the Rwanda disaster? Were you working there when Newsweek finally decided to dedicate its cover to Rwanda on August 1, 1994?

I absolutely love it.

I was working there in 1994 as a freelancer putting together their contest entries. This is a wonderful prime example of how one should look at Newsweek. As a magazine we supported several photographers covering the genocide in Rwanda, among others Gilles Peres, whose work was phenomenal. But the fact that you support it doesn’t mean that the magazine is going to run it, because remember the appetite for showing harshness constantly compromises the conversation in a news room. People are terrified by statistics of around 800,000 people’s death. In the end they paid tribute to it. But that particular piece, which I particularly adore and saw much later – three months before Newsweek finally covered Rwanda for the first time – it was all about illicit love affairs. Newsweek, I am sure, was pitching that story too, but the attitude of the editors back in New York was sometimes far removed from the harsh realities of life. We ran virtually nothing on Syria when the worst was happening, and that’s not because people weren’t writing to us at Newsweek and sending us material. We had layouts, we put them in front of the editors telling them that we had to do this and be responsible. We were addressing Syria, but in another way, except that the magazine was so removed from wanting to deal with death and disruption. I had, because of my position, large numbers of people writing to me every day, and it was simply awful to tell them ‘no’. We did not support Tim Hetherington, but I put his picture on the wall; that’s another story, entirely. No one supported him, including Vanity Fair, and that’s symptomatic of the general state of affairs. Most of the people that were out there in war zones were not supported even when they had notoriety.

With your job, you must have been exposed to other people’s deaths from the privileged position of your office in New York, like Tim Hetherington’s case. Have you ever thought of getting involved and joining your photographers in the war zones?

Part of me always wanted to do that, but I don’t know if I have the courage to do so. I lived for years in Asia – I lived in Pakistan in 1985 – but with a camera it’s different. I would like to go to Libya or Egypt and experience that sort of thing. I wish that actually Newsweek had more frequently encouraged that kind of engagement in the field but they didn’t.

Tim’s is a unique case; he was a friend of mine. Talking about the relationship between a photographer and an editor, Tim’s main body of work was channelling through Vanity Fair. I know a lot about that because I helped him get work with Vanity Fair, but he would always end up bringing his work to me at Newsweek. The reason is because when he first came to New York he came to see us, and we developed a relationship of visual narrative. I will always feel guilty to have not supported him more frequently. I put Tim’s work on the wall because we got the film first, and his family gave us permission.

Can you share with us the best and worst memory of your job as the senior photo editor of Newsweek?

There are several ‘best moments’. Working with creative people in the field was always fascinating. My job was endlessly engaging, meeting those photographers who had the courage and the creativity to go out and gaze at the world and try to translate it to us with a still picture or video is a great and privileged conversation to have. I am always indebted to that. Sadly, one can hardly make a living doing it anymore because the power shifted more towards cheap photography.

There are countless ‘worst memories’! The biggest regret was not being able to support people in perilous situations. It happened with Van der Stockt in Falluja; he was a contract photographer for Newsweek. I wanted to move on that quickly and make sure that he was secure. Someone came up to me at Newsweek; he was paranoid that Van was on assignment for us. At that moment the conversation should have been: ‘Yes, sure he is. What can we do?’, but, on the contrary, they were relieved to find out that he wasn’t.

Same with Tim, we needed the resources of our company to get his body out of the country, because for years he has been sending us material and giving us his energies and courage. Let’s do our part, come on!

It also happened in 2009 with Teru Kuwayama, a freelancer on assignment for Newsweek. He was returning to Islamabad with Lynsey Addario, coming out of the refugee camps. The driver fell asleep at the wheel, killing himself in the process. They were both very badly injured. When they were taken to a hospital in Islamabad, the then chief correspondents could not have been less helpful. Had he been a writer they would have moved the machine, but Teru was isolated and it was only thanks to the good graces of friends of mine at The New York Times and CNN who kept an eye on him that he survived. In a 24/7 scenario when one is at a hospital in a difficult world, I just could not figure why they didn’t reach out to all the resources to ensure that he was fine. It really infuriated me. I had lived in Pakistan years before then and it always makes me cry this story. I called friends that I met while living there and they took care of him, but the very magazine I was working with seemed to be completely removed from it.

As for the driver, I still don’t know if they gave any money for the driver’s funeral expenses or to his family, my guess is if they did it was very minimal, but they were extremely cagey. I have never forgiven them for that. You’ve got to stop what you’re doing when someone is injured in a difficult place.

It’s not just our organisation. When Patrick Robert was seriously wounded in Liberia, other correspondents and photographers stopped what the fuck they were doing and took him to the hospital. It was not about deadlines anymore , it was about morality and ethics. That to me has been lost, narcissism and the self seemed to take over. Of course you can’t generalise, but there seems to be no cumulative sense of making statements that in time, historically, will reflect on genuine concern for the world. Why the fuck did we get into journalism to begin with? To make a difference which is hard enough, but it’s embarrassing what they were putting on the covers. Newsweek had always been devoted to hard stories and they simply walked away from it.

Let’s go back to the exhibition.

Did you like the exhibition?

I liked it. It is very intense! I was a bit confused by the different hierarchies in the installation. If you look at a framed print by a famous photojournalist and then smaller spreads and blown up covers… I would like to understand what sort of learning experience was intended for the visitor.

It’s very eclectic to work in a magazine. You must understand that a weekly has an incessant nature. One is never working on one story. You are jostling up to 15 at any given moment, and say by Thursday they would have killed 13 of them and added 7 more. It is eclectic; a lot of decisions are made instantaneously.

So you wanted to render this aspect with the installation?

That’s how it became. In terms of the coherence of the exhibition, I just took a deep breath and said we will face it when we get there. And it worked I guess. It is also thanks to four or five very special volunteers that helped us in Cortona who worked cumulatively and it became the exhibition of the whole team. They loved it and I loved that they loved it. We did a show together. If he had more time I would have covered entire walls to make it a completely overwhelming experience. People in Cortona, Arianna and Antonio generated the prints idea, as they wanted them to travel to another venue afterwards.

Plans for the future? Will the exhibition tour?

Not the crazy bit, the organic version of it, the prints. I wanted it to represent the schizophrenic reality of a weekly magazine. It is very difficult to put together a weekly magazine, and it usually fails. It’s better if the images in it drive thought. But editors usually lack aesthetics and a good example is the Obama portrait. I have tried to put that on the cover so many times which would have been slamming, it would have stood out anywhere in the world. It’s an attempt to break conventions of photography and generate interest in energy and for me that picture absolutely does that, I don’t care if it’s out of focus.

Especially now. There was so much hope and expectation in Obama that reusing that image now, after his government was partly disappointing for a lot of people, to me it makes a lot of sense…

Si, you read that in the image and it works for me! I am in this game because I am interested in history. All that I do is to be involved in addressing issues today that soon enough will be history. I read a lot of history. You get that when you grow up in Virginia where they are obsessed with the Civil War.

I look at some contemporary issues as if they were already part of our history, even if they are happening right now. The people who are out there must possess vast amounts of sensitivity to make pictures in a way that they will last. Most magazines are quick reads and a lot of editors don’t think about pictures in the same absorbing way that I do. I want people to look at the picture for a long time. A quick read is boring and insulting to my intelligence. Of course, with a weekly magazine you have to do the quick read thing but if you want to address an issue in a much more energised and creative way you have to acknowledge first of all that it wasn’t a ‘quick read’ to get there for the photographer, that it takes time. I want the photographers to write more because often the writers irritate me with their lack of trust in the integrity of photographers. With the medium of photography, you have to be present there. It’s not always true with writers. They can be in a hotel writing their stuff. Photographers have to be in the story, but get me right on this, the word came first, and I love the word.

A question from our editor in chief Manik Katyal: ‘With digital booming in the magazine world, the print edition is going to get more special and precious. What’s your opinion about it?’

Some are celebrated as printed editions but no one can turn away the fact that we have to put it online – it’s a demographic thing. My 15-year-old does not look at a lot of magazines, he searches online. What we need to do is to create some kind of engineering brilliance, so that you can take your computer to the beach to read an article. Right now paper is still essential for me, but remember I am 51, I like paper. Some magazines remain linked deeply to printed matter; The New Yorker is an example of one of the best magazines in the world, and people still buy it!

People are drawn to paper. It is tactile, provides an intimate experience. If we only do computers, our sense of touch and feel and smell is going to be adulterated in a terrible way. But of course there are fundamental questions about expenses and resources. A bookstore remains forever central to my life and for those who don’t get it, I always feel very sad for them. The digital future, however, remains obscure.

One last question: Tell us a bit more about your current projects: Seen/Unseen and Fovea – the latter is such an intriguing word – ‘a small depression in the retina, constituting the point where vision is most clear’!

Fovea – I take too much credit for that, but the frustration of not being able to publish enough material led groups of us to say: ‘How can we do more?’ Fovea was one of those ideas. As a group with Stephanie Heimann and Julien Jourdes, we decided to make something. Fovea was born as a place to publish ideas, and broader bodies of work to overcome the sense of lack produced by a single image in a magazine. The idea was similar to Foto8. SeenUnseen is something I started with Jake Price and that was also based on the same idea: all these people pass through New York; my wife had a wonderful downtown space called the Bubble Lounge and we organised a number of photographic shows to explore Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan etc., with no compromises.

My most recent project is called Screen, a news platform focused on words and experiences of photojournalists, to create, support, and deliver powerful visual and narrative stories around the world. It’s a cooperative of people – Liza Faktor of Objective Reality, Ivan Sigal of Global Voices Online, Bjarke Myrthu of Storyplanet and Frank Kalero of Ojodepez. We are a bit spread out so everything takes time. I have also been given a fellowship by the University of Michigan to work on it. It helps!

Photography Interviewed by Federica Chiocchetti

Federica Chiocchetti is a researcher of photography and literary theory at the University of Westminster in London and an independent curator. She is a contributing editor from Europe.