China –

Beijing Silvermine started in May 2009 out of my meeting with a man called Xiaoma, who works in a recycling zone north of town, where part of the city’s garbage ends up. Over there, some specialize in plastics, some in beer bottle caps, but he solely concentrates on trash containing silver nitrate, which essentially means hospital x-rays, cd-roms, but also negative film. Before drowning it all in a big pool of acid in order to collect this precious silver, he agreed to sell me negative film by the kilo, and that’s how the Beijing Silvermine project was born.

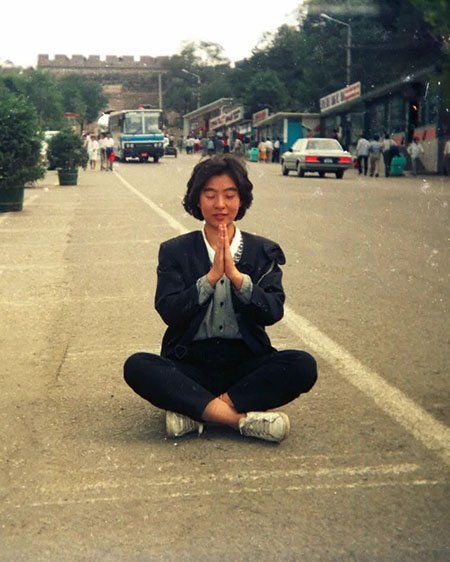

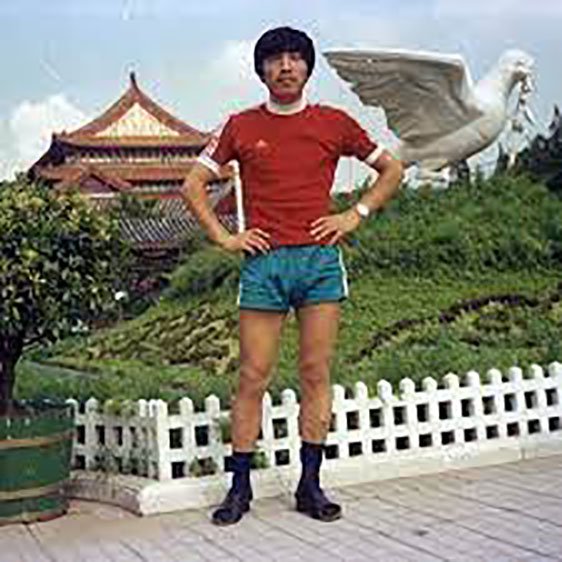

Ever since, I have been repeating this collecting process every month, and the archive now counts a little more than half a million negatives. These rice bags filled with thousands of rolls of slobbery, stinky, dusty, scratched, crumpled and humid negative film, have allowed me to access a highly codified visual universe, where the subject is always standing up straight at the center of the image, looking into the objective. In these photos, there is a paradox between this total absence of spontaneity on one hand, and on the other hand the inherent complicity between the photographer and the photographed; in China taking pictures is always a ritual, it always involves posing and necessarily consent. The results are these unpretentious, often quite funny, and undoubtedly endearing images. Beijing Silvermine is a unique photographic portrait of the capital and the life of its inhabitants following the Cultural Revolution. It covers a period of 20 years, from 1985, namely when silver film started being used massively in China, to 2005, when digital photography started taking over. These 20 years are those of China’s economic opening, when people started prospering, travelling, consuming, having fun.

Video credit -Emiland Guillerme

While reviewing this archive severall times, I was constantly looking for these few cliches which stand out in this artform that is souvenir photography. I’m thinking of a man sitting on a crescent moon made of stone looking out towards the city, or a woman in an apple green dress standing in the middle of a deadly fight between a shark and an octopus, or another hidden in a field of 15-feet-tall daisies. Also, a number of unexpected series naturally started standing out. For instance, at the end of the eighties, as Beijing households started modernizing, it was quite usual to be photographed next to your latest purchases… I therefore have a tremendous amount of portraits of people posing next to their refrigirator… With these photos we enter people’s homes only to discover posters of Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Sylvester Stallone… at a time when China is only starting to open up to the West. Through all these souvenir snapshots taken by the anonymous and everyday Chinese, we’re in reality witnessing the birth of post-Socialist China.

Naturally, it is fundamental that this archive is able to live through the outlook of others. One year ago, I invited the young Chinese artist Leilei to come check out my garbage. He offered to generate an animated film from these images. His idea was to create a stroboscopic film at a rate of eight images per second, showcasing a certain number of series with a common denominator. This could for instance be a similar pose, or a horizontal sealine, a sunset, Ronald McDonald, or even Chairman Mao’s portrait on Tiananmen Square. From there, Leilei organised these pictures – a colossal task – to produce a sort of imaginary and slightly psychedelic stroll. His approach was radically different to mine, wanting bulk and repetition, rather than distinctiveness.

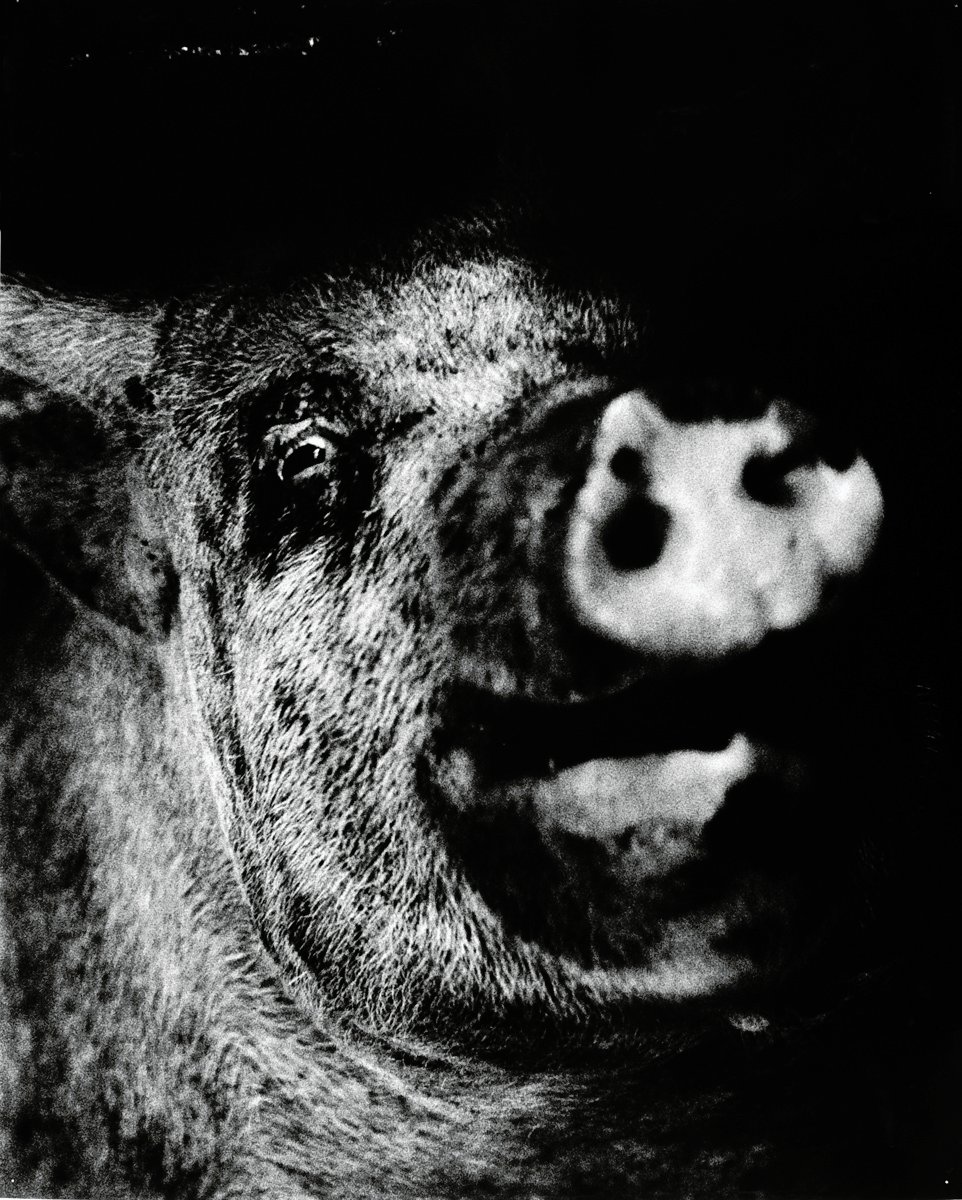

Following on in this spirit of collaboration, as a special commission for FORMAT13, Melinda Gibson will make a series of interventions for the exhibition. Delving into such an enormous archive will be the first step. Working through the layers of time and history, both culturally and physically play a fundamentally important starting point in this collaboration. Her initial examination will be searching for imagery that is abstracted by the formal qualities of the medium. Scratched, partially destroyed and chemical ruined negatives that offer up a new way to see this archive and of a medium that has become defunct and talk of the historical and technological changes that continue to help and hinder our tool. Using this as a starting point, she will examine these formalist qualities, pulling apart the very essence of these images, using mixed media, pencil, paint, and etchings to reassemble images that were saved and can now be brought to light in a new way.

Video credit -Emiland Guillerme