Emaho: Hamed, your work crosses architecture, research, and teaching. Can you share what inspired you to pursue these three paths, and how do they influence one another in your creative life?

HK: I have an unconditional love for architecture. I must say that architecture is a much larger category than building. My interest has been gradually shifted from built forms to imagined, drawn, and written forms of architecture. The type of research and teaching I do is also very much linked to this wider understanding of the field. They are less about clinical research and formal teaching, rather centred around creative and applied forms of research and pedagogy; those that could be generative of new ideas, discussions, and imaginations.

Emaho: “Gabriel Guevrekian: The Elusive Modernist” is described as a photobook shaped by micro-narratives. What drew you to Guevrekian as a subject, and what makes his story relevant today?

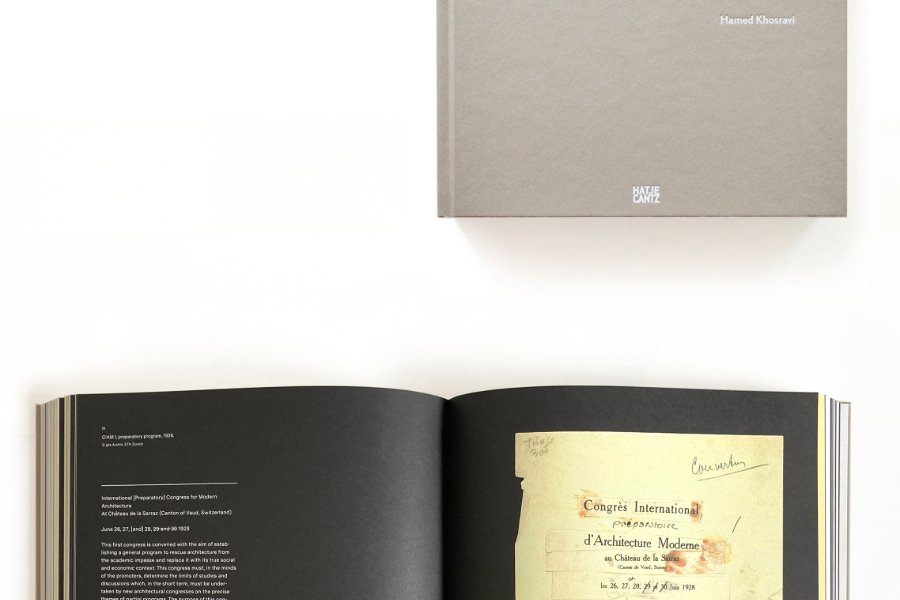

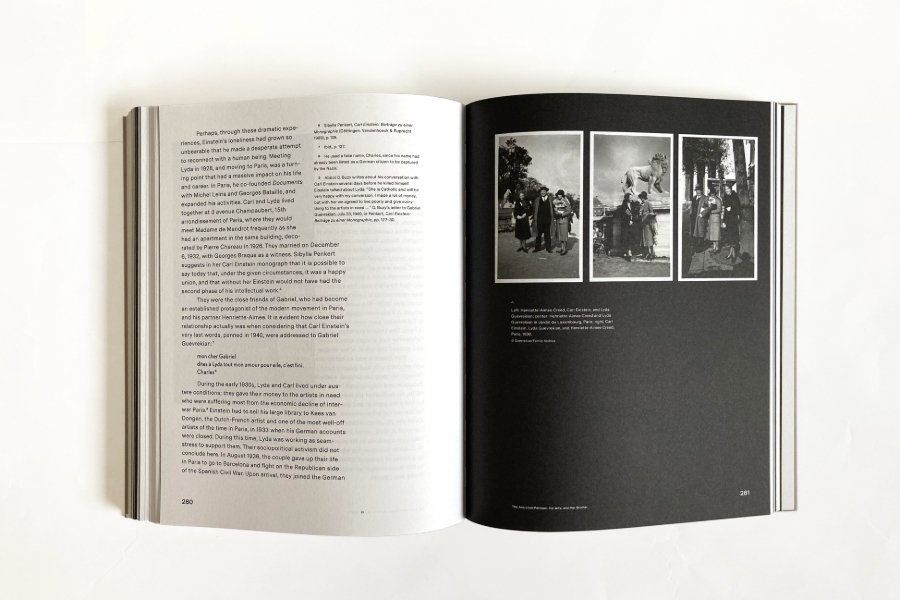

HK: I wouldn’t say that it is a common photobook; the publication is richly illustrated for a very specific reason. The protagonist of the book, Gabriel Guevrekian, has been central to the history of Modern Movement in art and architecture, however he did not find his way to the official narratives and canons of the field. This might have been result of his constant movement from one country to another or due to the fact that he was not European and did not have a strong tie to any of the influential figures and historians of the period. The book aims to factually illustrate Guevrekian’s central role. The format and the size of the book was designed based on two main sources of information in the research: Photo albums and letters.

In the process of making the photobook, what did you discover about Guevrekian’s character and journey that surprised or challenged your initial assumptions?

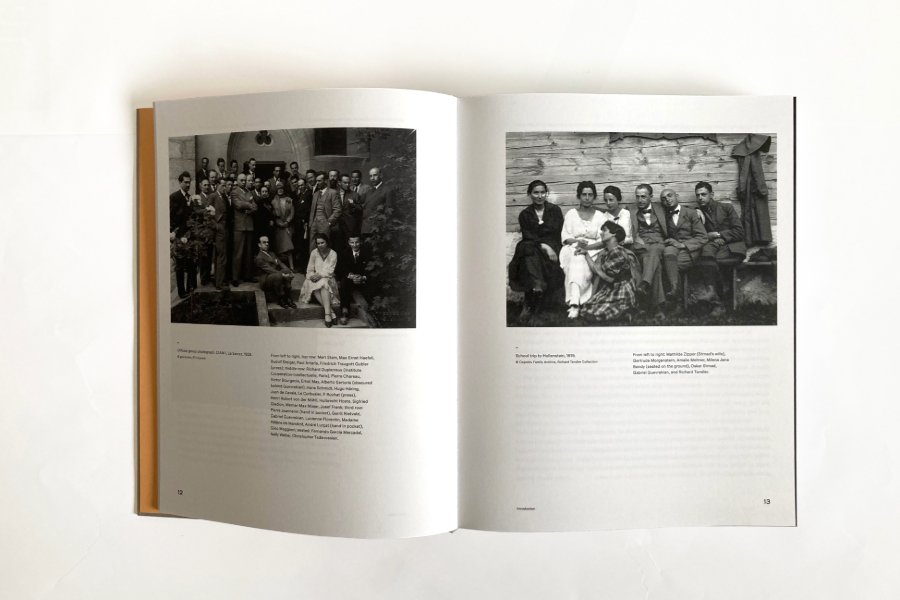

HK: The research on Guevrekian is a continuous inquiry that is still ongoing. The book was an attempt to frame part of his multi-faceted life and professional career and situate it within and against dominant narratives of the Modern Movement. Beside his architectural career and projects, what fascinated me was his affinities with key influential artists such as the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar, the Avant-garde artist Tristan Tzara, or the Anarchist art historian Carl Einstein, next to his controversial relationship with eccentric architects Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos.

Guevrekian’s career spanned several continents and cultures. How did this sense of movement and reinvention inspire your own approach as an architect and educator?

HK: I have been moving countries myself too. I can’t say that mine has been anything similar to Guevrekian’s life, but what I could say is that I realised how difficult and, at the same time, liberating it could be. Guevrekian’s nomadic life was triggered by a series of choices he made, but most importantly, lots of external forces that made him move.

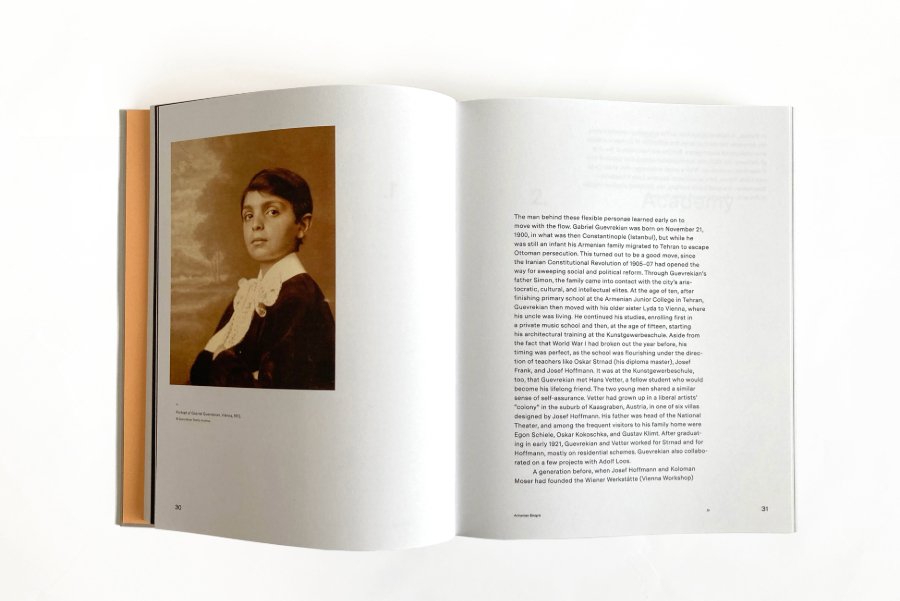

Born in Istanbul in an Armenian family, Guevrekian grew up in Tehran and then moved to Vienna to study architecture at the Kunstgewerbeschule. He later worked with Oskar Strnad, Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, Henri Sauvage, and Robert Mallet-Stevens. His famous designs include the Cubist garden for Villa Noailles in France and two houses for the Vienna Werkbund exhibition. Not yet thirty, Guevrekian was recognised as one of the protagonists of the European avant-garde in Paris. During the 1930s, he spent a few years in Iran designing public buildings and private villas. Later, after World War II, he assumed teaching responsibilities in Europe and America.

Such condition made him to take any opportunity and make the best out of it. This meant that for him assets such as fame, legacy, and somehow social network and connections had to be replaced by dedicated effort and determination. Such approach inspired me a lot.

How did you go about researching and sourcing images, documents, and anecdotes for the book? Were there moments that felt like uncovering pieces of a lost puzzle? Did you uncover anything unexpected in archival research or in private collections while working on the book? If so, can you share a memorable moment?

HK: In preparation of the book, I visited more than 40 archives and collections, each opened a new insight on Guevrekian’s life and character: Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle falling into place. I must say, when one works with the archives, each piece is unique and somehow unexpected. During the research I came across many fascinating letters. In fact they helped me a lot to track Guevrekian’s movements across the world. Letters are amazing archival documents, beside their content they have a date and two addresses, that immediately locate the corresponding people in particular time and place. Some of these correspondences helped me to find two of Guevrekian’s modernist villas he designed and built in Tehran. It was such a revelation to visit these rather forgotten gems in almost after nearly a century and realising that I had walked past them for years but not recognising them.

The photobook format allows for both visual storytelling and written narrative. What was your process in balancing these elements to reveal the complexity of Guevrekian’s legacy? Please talk about his connection with Iran.

HK: One of the main purposes of the book was to communicate the history of Modern Movement and in particular Guevrekian’s legacy to a wider public. For this reason, together with Marco Ugolini, the graphic designer of the book, we decided to make the visual narrative of the book as important as the written one. This idea was developed to the extent that one could just flip through the images and letters and have a complete narrative. We also decided to use three paper colours, dark grey, light grey, and yellow to distinguish archival documents, reviews and interviews, and Guevrekian’s own writings. Such design principles allowed the book to be written in English while comprehensible through the universal language of images and photographs. This helped the book to reach to non-English speaking targets like general Iranian public.

As a teacher, do you see parallels between Guevrekian’s vision for cross-cultural exchange and your own philosophy in the classroom? What do you hope students learn from his life?

HK: Guevrekian’s unique position in linking East and West and establishing cross-cultural dialogues is a perfect example through which we could rethink the dominant historical narratives and pedagogical models taught at universities and schools of art and architecture across the world today. In light of “de-colonial” attempts to diversify make inclusive the educational models and to question the power-relations that have historically shaped them, revisiting Guevrekian’s legacy could give us a wider, if not an alternative view of how the recent history of architecture and Modern Movement developed, disassociating it from Euro-centric narratives and canons. This could (hopefully) allow the students to cherish their unique cultural, social, and historical background, enabling them towards a more inclusive and divers knowledge and practice of architecture.

Please take us through the process of editing the book. It has been designed beautifully. What inspired you to have this design language in mind? What do you hope readers and viewers will take away—about Guevrekian, modernism, or creative life in general—after experiencing your photobook?

HK: There are many threads that came together in design of the book. The overall graphic design, typeface and format follows what is known as Modern Swiss Style that is a tribute to Guevrekian’s design philosophy. However, many design decisions were taken in line with the accessibility of the book and making it easily communicable to a divers set of target audience, while maintaining an integrated form and content; small decisions such as including letters in original languages (as well as their English translation) honouring Guevrekian’s multi-lingual skills to formatting the book in episodic and cinematic arrangements; chapters that do not necessarily follow a linear historical narrative and sometimes have overlaps, flashbacks, and jump-cuts.

Modernism is often defined by its icons, but your book seems to foreground marginal stories and overlooked contributors. Why is this important for our understanding of architectural history?

HK: That’s absolutely correct.

In fact the book attempts to portray Guevrekian against those frames that have dominantly foregrounded white European men as the main protagonists of Modern Movement, while avoiding those tropes, it tries to acknowledge Guevrekian’s multi-faceted character. All of his various pursuits, and the homes and nationalities he held in Iran, Europe, and the United States, led to a serial adoption of personae. Being an architect—as Guevrekian ably demonstrated—was no longer simply about designing buildings; it was a matter of cultivating a political persona, proselytizing an ideology, and keeping a shared spirit alive.

How has working on Guevrekian’s story influenced your own design practice or research interests? Did the project change your perspective on architecture or artistic identity?

HK: In studying and analysing the work of Guevrekian, what has been very inspiring for me is his total control over the geometry and spatial organisation. This is present in his drawings as well as various details of built projects, from furniture to gardens, to villas, and public buildings. It is difficult to assess whether such inspiration has changed my own practice, however one aspect that has become more important for me and perhaps more present in my work is applied techniques of abstraction that is at the core of Guevrekian’s practice.

Is there an anecdote or discovery from your research on Guevrekian that you found personally moving, or emblematic of his elusive character?

HK: One of the key periods of Guevrekian’s life that has remained unknown is between 1940 and 1944 when he abandoned his practice and refused to work under Vichy Government in France. He moved to South of France and lived by subsistence farming. Known correspondences with his sister Lyda and his brother-in-law Carl Einsten suggest that Guevrekian was in touch with, or involved in, anarchist resistance group across the border in Spain. While there are yet no concrete evidence to shed light on his activities during this period, what remains unquestionable is his commitment to political and social activism at the cost of leaving his flourishing career aside.

What advice would you offer to emerging architects, artists, or scholars who aspire to create work that bridges research, design, and teaching the way you do?

HK: Simply to be projective and imaginative! History has been taught as inseparable part of our profession. While many pedagogical models treat historical research and design as separate realms, what I would always advice the students and academics is to reject the division and found the relevance of historical research in understanding the present and designing the future. In fact, Research-by-Design is the model and key methodological approach we apply in our Projective Cities programme at the Architectural Association School of Architecture.

You have a broad practice (studio projects, exhibitions, publications). How do you balance or integrate these modes (architecture, art)? How do you see the intersection of architecture and photography — what does photography bring to architectural thinking (and vice versa)?

HK: Photography both in terms of techniques and methods of seeing has been central to my career as an architect, writer and educator. It is not only a way of capturing a moment, a building, a landscape, or a subject but to construct it. In this sense, I work with photography as a design tool that also has representational values. One of the instruments shared between architecture and photography is the frame as a device. Whereas architecture’s frame is mainly applied to space, photography’s main substance is time.

Hamed Khosravi