England –

Simon Baker of Tate Modern London is the institute’s first curator of photography and international art and is held in high esteem for his role in formulating the museum’s evolving photographic strategy. EMAHO sat down with Simon at the 2013 Les Recontres d’Arles Photographie Festival to discuss his thoughts on this year’s talent and the approach he takes as a curator in acquiring photography for the Tate collection.

Manik : You’ve mentioned in one of your previous interviews that the aim for you as a curator is to present something that has never been seen before, to reveal and to uncover some aspects of work that we, the audience, may not always know about. Were there any unique aspects of the work at Les Recontres d’Arles that you found interesting?

Simon : When I was looking at works for Arles, I was looking at the idea of discovery, which is the meaning behind the [Discovery] award. This could be in many different ways, it could be the discovery of a new young artist, somebody who has maybe just finished art school and their work has not been seen or, in another case, somebody who in fact was well advanced in their career but hadn’t had the exposure or the opportunities that others might have had. I think both were very important. Yet another case involved works that weren’t shown in France very much, so something that could have been seen in a lot in America but not so much here.

Manik : Along with this, you have also been really attracted towards photography in Japan. Before you became a curator, you had studied the works of Minoru. You have also been deeply influenced by Moriyama. What do you think of what’s happening in contemporary Japanese photography?

Simon : The history of Japanese photography is quite distinct from what we usually think of it, particularly post-war photography, because so much work was in black & white. The dominant tradition in post-war work has been colour so what was interesting to me about Japan (particularly people like Takahashi, Moriyama, Nakahira) is that they made this new visual language in black & white, which is quite relevant for this year in Arle because of the theme being black & white. I think Japan is something that we underestimated for many reasons, some of them cultural, some of them to do with language, but I think it’s important to fully understand the significance of Japanese photography.

Manik : What in particular attracted you towards Japanese photography?

Simon : I didn’t know so much about Japanese photography before working at Tate but I think the thing that attracted me once I started doing research was particularly the photo books; Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki make fantastic books very regularly. I find that this is a great way to see work. If you think about the communication of ideas around the world the book is something that travels easily, I can see the same book in London that you can see in Tokyo or wherever. I think that is very important.

Manik : So it was the photo book aspect that attracted you?

Simon : One of the main things, yes.

Manik : Recently when I was in England in March I interviewed Brett Rogers in which she implied that it was becoming a trend, that now the world is really intrigued by Asia’s fast evolving photography scene.

Simon : The other great thing about festivals is that you get to see a lot in one place, so if you go and see the Sao Paolo photo bi-annual then you’re going to suddenly see lots of artists you’ve not seen before and I think that’s very valuable and important from the point of view of rebalancing the geographical centre. The centres are all changing, the sense of Europe or America as a kind of home of photography is not there anymore; everything is moving away. I think that there is much interest now in a broader understanding of where the work is being made. The past few years have seen several photo exhibitions in the Middle East and South Africa. These events are breaking the old norms.

Manik : In this year’s edition of Arles, are there any photographers that you are looking forward to seeing? Are there any countries or unit of photographers from a specific country that you are looking forward to?

Simon : There’s such a range of work on offer this year; the theme is excellent – the focus is on black and white, but it’s not the only thing. One of the most stunning installations is Wolfgang Tillmans’; there’s not a lot of black & white in his work but, having said that, they contain some really wonderful and surprising things. The great thing about Arles is the opportunity it provides to see a great show, say, of Sergio Larrain, a Chilean photographer whom I knew but hadn’t seen a show of, alongside a Guy Bourdin show, who is a very famous photographer but here you see works that you’ve never seen before, like portraits and little contact prints. Then there are photographers whose names you’ve not heard of before. This balance between rediscovering, re-presenting and completely new work I think is excellent.

Manik : Are there any emerging photographers whose work you liked here in Arles?

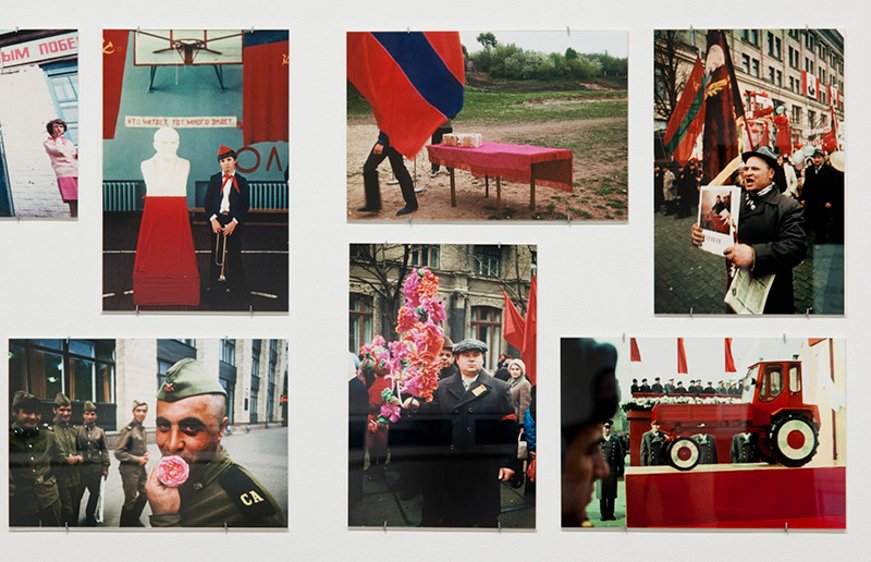

Simon : Actually, one of my favourite photographers turned out to have been dead for a few years. He was a Russian photographer, a new discovery for me. I’d never heard the name, never seen the work before. I thought it was absolutely stunning, and was very disappointed to find out that he had died several years earlier, which is tragic. Anyway, that was a great discovery of mine. I think there’s always something like that every year. There’s also Antony Cairns who’s in the big atelier; he’s in the same space as Pieter Hugo. Cairns is a very young photographer from London who is working with black & white, printing on metal, some wonderful objects and incredible images – it’s very, very exciting. It’s strange in a way to come from London and see a young British photographer showing at Arles but it’s great to see it here. I don’t mind seeing it here rather than London. I hope he will have a show in London too.

Manik : In one of your earlier interviews you said, ‘Photography is seen at its best when in a series’. Is there any specific reason why you say that?

Simon : One of the reasons I said that is to make the point that for many years, at Tate anyway, the main photographers who were shown were people like Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth who work on these huge tableau-like paintings. Or someone like Jeff Wall who is talking the language of the dominance of a huge painting. What I think is interesting is to think of other kinds of work that maybe aren’t one huge impressive object but a series. Photographers work in large groups of works; they take large prints and pictures and make prints in groups; they make books which are sequenced very carefully. I’m not saying it’s the only way to understand photography, but it’s a key aspect of the specific quality of the photographic medium that the series is a very powerful thing.

Manik : So as a curator do you only work with series?

Simon : No. I just think it’s something that we need to attend to, if a work is made in series we should try and show as much of the series as possible and not just pick one image out of a group of 20. I realise you can’t always do that [use a series] but I think it’s important to try.

Manik : In 2010 you discovered Taryn Simon here and curated her work at Tate. Is there anything specific that you are looking for from this year’s festival?

Simon : There are several things that my colleagues and I have seen here that are interesting. I mentioned Guy Bordin and his previously unseen black & white works that are extremely beautiful. It would be great to think about something like that for the Tate but there are so many things here – for instance Alexander Slyusarev, the Russian photographer – that we would love to show. We work in a kind of research mode. We’re not trying to hire people here or curate things that quickly. It’s about being here to research, to look around and to gain a better understanding of new things.

Manik : As a curator, is it always a good idea to visit more festivals, or is it better to attend specific ones?

Simon : As with any museum, we have limited resources for travelling and going to places so we go to the places we thing are going to be the most useful. So this year I will visit Tokyo Photo, which I’m looking forward to, and one of my colleagues will go to Unseen in Amsterdam, which is a really great new fair. It deals exclusively with younger artists and unseen work, which I think is a fantastic idea.

Manik : A lot has been happening in Asian photography. There are a number of photo festivals coming up like Delhi PhotoFestival, Bursa, Angkor, Phnom Penh and, most recently, Chiang Mai. Where do you think Asian photography is headed?

Simon : I think that is a difficult question for me to answer, as I am not an expert and haven’t been to those festivals yet. But I think Asian photography, on the whole, is opening up enormously. Just to take Japan as an example of a place that I do know, there are huge photo fairs – Tokyo Photo for instance, which is fantastic. There is a new one in Kyoto called Kyotographie. What RongRong & inri are doing in China with Three Shadows is incredible. Globally, photography is becoming more popular and accessible to audiences and that’s being reflected in this enthusiasm for new events and new places.

Manik : Are there any other festivals in Asia you are looking forward to?

Simon : The way that Tate is organised is that we have specialists who work on different regions as well as different medias, so I have colleagues who are dealing with SE Asia, the Middle East and Japan and they go to a lot more things than I do. They have been specifically looking at a Sri Lankan photographer named Lionel Wendt, an amazing historic figure from Sri Lanka who was working in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. We’re looking at doing something on him at the Tate in the future, which I’m sure will be very exciting.

Manik : Anybody from India?

Simon : I hesitate to say this because I think she’s very much an international figure (rather than just being from India) but Dayanita Singh is somebody we would love to work with. She is somebody we are already considering as an appropriate artist for Tate. She’s reached an incredible status; her work is of an unbelievable quality – that would be an example of the kind of person we’d be very interested in. I don’t see Dayanita as just being an Indian artist; she’s a great contemporary photographer who’s making incredible work, beautiful installations. She is somebody whom we would show not just because she is from India but simply because she is a great photographer. I saw her work in a London gallery; she was also in Venice at the Biennale. She’s an international artist now.

Manik : Do you think there is a possibility that some photographers might get the opportunity to show their work internationally and some might not. The ones that don’t then miss out on the opportunity for someone like you to see their work?

Simon : That’s what I was saying about the importance of something like the photo book. Before I got seriously interested in Japanese photography, I’d never been to Japan. But I’d bought many, many books, which got me interested in it. It’s not necessary to visit the place to learn about it. Once your interest has been piqued it is necessary to go and meet artists, to go and see galleries, but to begin with it’s not important to have been there physically. I think publishing is really important. You see it here at Arles where smaller publishers are bringing out younger people’s work. We had a book launch yesterday for a photographer who did work in Siberia; he’s a young photographer, and it’s his first book, that’s exciting. He’s from New York, the work is about Siberia and he’s launching it in Arles.

Manik : In India, only a handful of photographers actually have photo books. There isn’t much of a self-publishing culture and not too many publishers who support this kind of work. I think these photographers could miss out on opportunities.

Simon : It’s important to think about other kinds of publication, maybe magazines or having an online presence, something that gets ideas out and about. I don’t see there being any lack of it. If you go down to the atelier and see the book publications from last year, it’s very diverse in terms of geography, gender and ethnicity. There are so many great books being made. And if, as you say, there isn’t a great photo book tradition in India, I’m sure it will come. It’s exploding everywhere else and one of the reasons for that is this difficulty – that there aren’t so many galleries for photography. I understand that it’s financially difficult for photographers to survive on print sales but the book becomes a beautiful calling card, a way for people to easily see your work, and it being understood more widely.

Manik : Francois Hebel mentioned to me in an interview that with the coming of digital imaging it seems photography is now mainly colour and there is no shame in being a photographer who uses colour anymore. In fact it is black and white that has disappeared. What’s your take on the ‘Black’ theme at Arles this year?

Simon : I think it’s very exciting because what you’re seeing is not only the persistence in the use of black and white by very famous photographers who continually work in black & white, like Moriyama, but you are also seeing people experimenting with different kinds of processes, like re-exploring 19th century processes and making handmade objects using all kinds of photographic paper. It’s really showing that the black & white photograph isn’t just a small format silver gelatin print – it could be any kind of format and that’s very exciting. Maybe it is a reflex reaction against the dominance of digital technology that is very simple – ‘Click, click and then it’s done’. Whereas these old analogue processes are much more sophisticated.

Manik : So you agree black and white still exists in the digital world?

Simon : Yes. If you have lots of money you can buy a very expensive Leica that only takes black & white prints or black & white digital files.

Installation view: Artist Rooms: Diane Arbus, Tate Modern, 2011

© Tate Photography

Manik : This year the focus was South African photography in which there were commissioned photographers from South Africa and France. What do you think about the initiative this year where they are trying to be more inclusive and have different photographers?

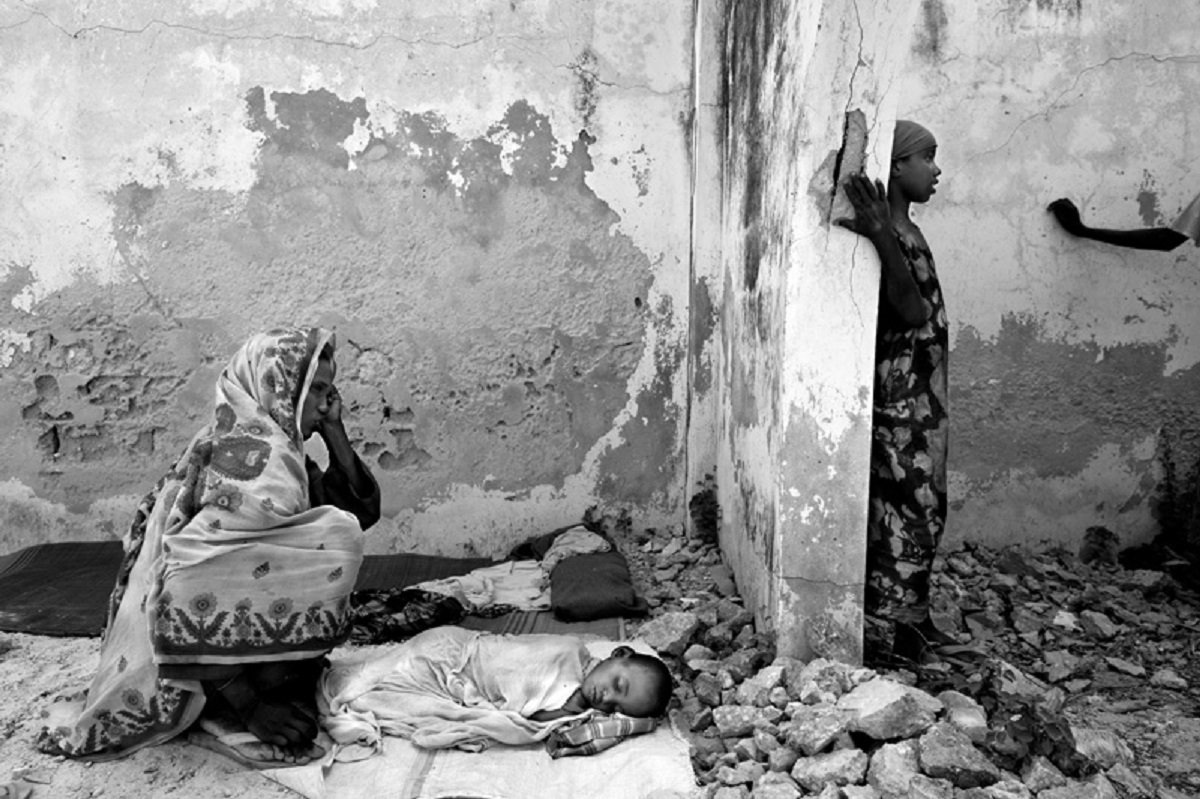

Simon : That was a nice example actually because you have some South African photographers and some photographers from outside the region. It’s more of an exchange and I think that is extremely important. When we think of South African photography we think of David Goldblatt, we think of Jo Ratcliffe and Pieter Hugo but there are many other fantastic South African photographers who aren’t so well known. It’s important to show their work, but it’s also necessary to provide some kind of context by showing the breed of photographers who travel to make their works. It’s an old documentary tradition – you know of going somewhere and photographing a place you don’t know. It is as valued a tradition as people photographing their own country.

Manik : Would you like to introduce something like this at the Tate?

Simon : We have many initiatives like that; we have something called Project Space, which is specifically to make bilateral relationships between institutions in other countries with the idea of broadening the geography. We’ve worked with institutions in the Middle East, Lima, Peru and Costa Rica. This programme is an ongoing programme that helps us to work between countries.

Manik : How do you select the places?

Simon : There are curators who are responsible for the programme. They build relationships with institutions in other countries, usually smaller institutions, not national museums but smaller and more flexible places.

Manik : Quentin Bajac (chief curator of photography at MoMA) recently expressed the opinion that ‘African, Latin American and Japanese photography deserves more attention’. What are your thoughts on this?

Simon : Of course I agree with Quentin. Latin America has been underrepresented for many many years. There’s a huge collecting community in Latin America so it’s not as if nobody is seeing the work; it’s just that it’s not being seen enough outside the region. I think with Japan, it’s up and coming; you’re starting to see a lot more work from there. I would also say that Eastern Europe isn’t being seen enough. There are many ways to reshape the dominant tradition. The simple fact is that a very small number of institutions in the world, some in Europe and some in America, have in the past really shaped the way everything happens. They’ve shaped the way we understand the history of photography. It doesn’t mean that amazing works haven’t been made in China or Japan; we just haven’t been aware of it.

Manik : What are your plans for Tate Modern this year? Is there any specific strategy or bodies of work you are interested in?

Simon : We’ve already got William Eggleston and Graciela Iturbide showing. We’ve just put up Miyako Ishiuchi, a Japanese photographer. Also Hrair Sarkissian, who is an Armenian based in Lebanon I think. We’re also doing experimental workshops for the Japanese side of things. And in November we’ll have a small Harry Callahan show, which will be very classic American. The following November (2014) we’ll have a big exhibition on conflict and memory, which includes artists from all over the world dealing with different contexts and cultures.

Manik : What in your view is the most important trend in photography these days? How would you reflect this in the choices you make at the Tate?

Simon : I think the issues that we discussed a moment ago…this question of handmade processes, the impact of digital processes on it’s opposite. So the idea of people going back, artists getting more interested in historical processes, working by hand, reenergizing the idea of the handmade object in photography.

Manik : One last question. Here at Arles a part of the exhibition is also showcasing in China. Would you be interested in something that is being shown at the Tate to be shown elsewhere too?

Simon : As I said we have this programme with Project Space and, of course, we always work with other institutions. The exact same shows will be at the Tate Modern London as there would be in, say, Beirut or Costa Rica.

Photography Interviewed by Manik Katyal