Emaho: You grew up closely connected to your father, the legendary artist Aydin Aghdashloo. How did that environment shape your relationship with art from an early age, and what did it mean to witness an artistic life from the inside?

Takin: My father’s life has been deeply shaped by his admiration for classical art. I grew up in a home filled with books, films, paintings, Persian calligraphy and miniatures, alongside Islamic and pre-Islamic Iranian artifacts and, of course, modern art. More than anything, witnessing my father make art on a daily basis – meticulously working through intrinsic details and processes – was foundational to how I learned to think about art. Art was not an abstract concept in our home; it was a discipline and a way of life.

Beyond his art practice, Aydin worked extensively as a graphic designer and illustrator in the 1980s. That side of his career also left a strong impression on me. As a child, I occasionally sat in on his meetings with clients commissioning illustrations and designs for book covers, magazine covers, film posters, and product packaging. Watching him navigate the tension between artistic ideals and client demands taught me early on about the realities of professional artistic life – particularly the importance of maintaining one’s integrity in practice.

Emaho: At what point did you realise that your path lay in curation and criticism rather than making art yourself, and which early experiences first introduced you to the world of exhibitions and galleries?

Takin: I migrated to Canada with my mother, Firoozeh, at the age of eighteen. A few years later, while I was still studying, she opened an art gallery called Arta Gallery in Toronto. The gallery was basically a one-woman operation, and I assisted her part-time with everything from operations and installing exhibitions to graphic and web design. It was a really valuable experience.

One of the gallery’s early exhibitions was a photography show by my late friend Sadegh Tirafkan. I knew Sadegh from Tehran and worked closely with him on the exhibition, which turned out to be a strong and beautiful project. During and after the show, he repeatedly encouraged me to change my field of study from computer science to art and to pursue curating professionally. A few years later, I did exactly that and enrolled in the New Media Art program at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Emaho: You have chosen to focus much of your work on Iranian art, both within Iran and internationally. What drew you to this focus, and why does it feel essential to you today?

Takin: After sixteen years in Toronto, I moved back to Tehran in 2017. Although I had followed the Iranian art scene from a distance, being back revealed its full complexity, diversity, and intellectual strength. Compared to Canada, Iran is a far more layered and historically charged society. Its political, social, and cultural circumstances have turned it into a long-standing battleground of ideas and ideologies.

Iranian art is inseparable from this context. It is shaped by history, resistance, negotiation, and survival – and for that reason, it carries genuine global potential. This is the cultural landscape I am drawn to, both personally and intellectually. I have a strong sense that my work in Iran can have a meaningful impact and contribute to tangible change, and that this is where my efforts are most needed at this moment in time.

Emaho: As a curator and art critic, how would you define your core purpose—are you more driven by education, preservation, provocation, or reframing how audiences see Iranian art?

Takin: My motivation encompasses all the purposes you mentioned. I see my role as building a meaningful bridge between Iranian and Western art scenes. Iranian art deserves a rightful place within global discourse, much like Iranian cinema has achieved over the past few decades.

My core purpose is twofold: to introduce Iranian art to international audiences with intellectual clarity, and to help raise professional and institutional standards within Iran itself. At the heart of this, however, is passion. I am deeply invested in both Iranian and Western cultural traditions, and in fostering a deeper understanding between them. Closing the cultural and intellectual divide that has persisted since the 1979 Iranian Revolution has been a long-standing ambition of mine.

I strongly believe in the role I can play as an educator – not only limited to the traditional sense of teaching in a classroom, but through exhibitions as educational spaces in their own right. I see the curating as a powerful tool for learning, dialogue, and reframing perception, and I am deeply committed to it.

Emaho: How do you assess the current Iranian art and gallery scene, both in Tehran and across the diaspora, and what do you think distinguishes it within the global contemporary art landscape?

Takin; I was recently in London and saw an excellent exhibition by Rasht-based artist Amin Bagheri at Ab-Anbar Gallery. Alongside Ab-Anbar, there are several Iranian galleries operating internationally that have succeeded by looking beyond their immediate diasporic communities and engaging in broader, more ambitious dialogues.

Within Iran, similar energy exists, though under far more difficult conditions. The Iranian economy and international sanctions have been devastating for the arts. Yet despite these pressures, two new art fairs – Tehran Art Fair and 8Fair – took place in Tehran in 2025, together featuring more than eighty galleries from Tehran and other Iranian cities. It was quite encouraging to see this level of activity, and I was impressed by the quality of the works presented, especially given that all of this occurred in a year clouded by severe political turmoil and the Iran–Israel war.

These developments point to the immense potential of Iran’s art scene. Tehran has a vibrant and increasingly engaged gallery culture, and public interest in the visual arts continues to grow. What the country urgently needs is fundamental political change to allow the energy, intelligence, and creativity of its young generation to fully blossom.

Emaho: Your exhibition Event: Iranian Contemporary Art and Shifting Realities at Cromwell Place in London, presented with Bavan Gallery, marked a significant moment. What sparked the idea for this show, and how did Alain Badiou’s philosophy influence the curatorial framework and artist selection?

Takin: The exhibition was inspired by the Women, Life, Freedom movement in Iran, which I understood through Alain Badiou’s philosophical concept of the Event. I was introduced to this idea through Slavoj Žižek’s book Event, where he expands on Badiou’s thinking and applies it to moments of radical rupture in history.

For Badiou, an Event is not limited to politics. It can take many forms: the birth of a new art form, a profound scientific breakthrough, or even the experience of falling in love – moments after which one’s perception of reality is irreversibly altered. An Event introduces something genuinely new into the world, making it impossible to return fully to the previous order of things.

When the 2022 protests began in Iran, I was repeatedly reminded of this theory. I was witnessing an Evental moment firsthand: a rupture in collective perception, particularly around women’s bodies, agency, and presence in public space. The exhibition was shaped around this shift in consciousness, bringing together artists whose works reflected not only political resistance, but the emergence of new ways of experiencing reality in the aftermath of this feminist uprising.

Emaho: The exhibition brought together artists from different generations. Which works or encounters within the show stayed with you most strongly, and why?

Takin: The exhibition brought together works by thirteen artists, all carefully selected in relation to the curatorial framework. It was an emotionally charged project, and every work remains vivid in my memory. I wrote individual statements for each artist, articulating how their work related both to the Women, Life, Freedom movement and to Badiou’s concept of the Event.

Two paintings by Shohreh Mehran from her ongoing Schoolgirls series were particularly resonant for me. One, painted in 2021, depicts a schoolgirl in full hijab sitting on the pavement reading. The second canvas, from 2023, shows two schoolgirls wearing school uniforms but they have taken off their headscarves. Seen together, these works captured the psychological and symbolic shift brought about by the movement beautifully.

Emaho: Are there emerging Iranian artists today whose practices you find particularly compelling? What about their work feels urgent or distinctive to you?

Takin: I am consistently impressed by the depth of talent among young Iranian artists, both inside Iran and in the diaspora. I recently visited the graduation exhibition at Kherad Honarestan, an all-girls art high school in Tehran, and I was deeply moved by the quality and confidence of the works

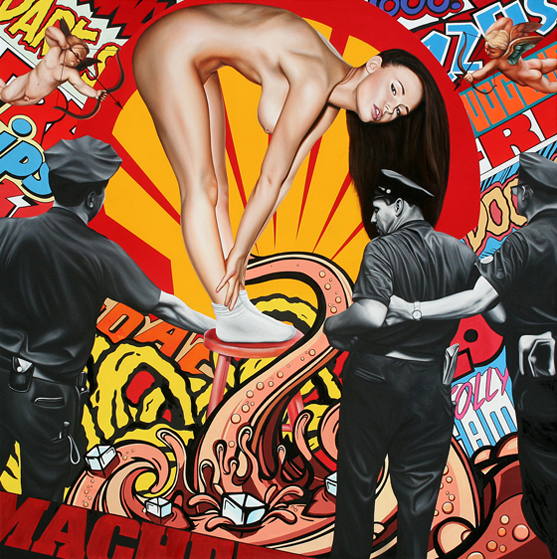

I am also interested in the practice of Istanbul-based multidisciplinary artist Parsa Mostaghim. His work examines the body, media, history, and politics through a language that is at once humorous, intelligent, dark, and grotesque – an approach that feels particularly relevant to our moment.

Emaho: Aydin Aghdashloo’s legacy is vast and complex. How have you approached documenting and presenting his work through books, exhibitions, and archival projects?

Takin: When I returned to Iran, I felt strongly that a comprehensive international monograph on Aydin’s work was long overdue. While two monographs had been published in Iran in 1994 and 2012, his oeuvre clearly required broader contextualization and international visibility.

Aydin has worn many hats over the course of his prolific career. In addition to his art practice, he has been an author, critic, graphic designer and illustrator, art expert and historian, collector, teacher, and museologist. Confronting the full scope of this legacy made it clear that the task ahead was substantial. I began systematically documenting his work and organizing his extensive archives, which include essays, correspondence, photographs, artifacts, drawings, and other materials dating back to the 1950s.

To give this process a clear structure and long-term continuity, I established the Aydin Aghdashloo Foundation in 2019. The central outcome of this effort was an international monograph, co-edited with Italian curator and author Marco Meneguzzo and published by Skira in 2024. The book is now available worldwide.

Emaho: What has been the most challenging—and the most rewarding—aspect of curating exhibitions centred on your father’s work while maintaining your own independent curatorial voice?

Takin: Working with family inevitably presents challenges, but it also offers unique privileges. I have lived with my father’s art for as long as I can remember. I deeply admire his technical mastery, his conceptual seriousness, his respect for both Iranian and Western classical art traditions, and his lifelong commitment to knowledge.

To ignore such a decisive influence would feel intellectually dishonest. Legendary Swiss curator Harald Szeemann’s 1974 exhibition Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us, which examined the life of his grandfather – a notable hairstylist – has long resonated with me as an example of how personal proximity can become a legitimate site of curatorial inquiry rather than a conflict of interest.

Aydin has been a source of great inspiration not only for me, but for generations of Iranians. I see no contradiction between maintaining an independent curatorial voice and critically engaging with my father’s multifaceted artistic life. For me, the two feel compatible and natural.

Emaho: Beyond projects connected to your father, which of your own curatorial endeavours have been especially meaningful, and what did they allow you to explore or articulate?

Takin: Every project I take on is an exciting journey for me, and I approach each one with great joy. One project I would single out, however, is the translation of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s A Brief History of Curating into Persian. I worked on it during the COVID pandemic, and it kept me meaningful company during an otherwise difficult period.

I am proud of this project because there was no financial incentive to translate a nearly 300-page book on a technical subject like art history, especially at a time when the Iranian publishing industry was – and still is – in a state of profound disarray. Working on the translation helped me maintain focus and motivation during a period of personal and collective hardship, and I hope it can be of similar value to aspiring young Iranian curators.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what are your ambitions for the global visibility of Iranian art, and how do you see your role in shaping its narrative in the years to come?

Takin: As Iranians, we first need to address the deep troubles we are facing at home. Our rich tradition of arts and culture has survived centuries of invasions and upheavals, but the past few decades have been particularly difficult for us as a nation. It is hard for me to imagine properly doing justice to Iranian arts and culture on a global stage without a democratic, secular, competent, and representative national government in place.

We need strong cultural and artistic institutions, supported by sustained public and private funding, in order to cultivate a healthy and dynamic art scene. At present, Iran’s cultural landscape is overly dependent on commercial galleries and market forces. Without addressing the deeper structural problems embedded in our political system, it will be difficult to move beyond this limitation.

Despite these challenges, I remain hopeful about the future of Iran and deeply optimistic about its young artists and curators. Curating, at its core, is about connecting cultural nodes and allowing a larger picture to emerge. If I can contribute meaningfully to that process, I consider my role fulfilled.

Takin