India –

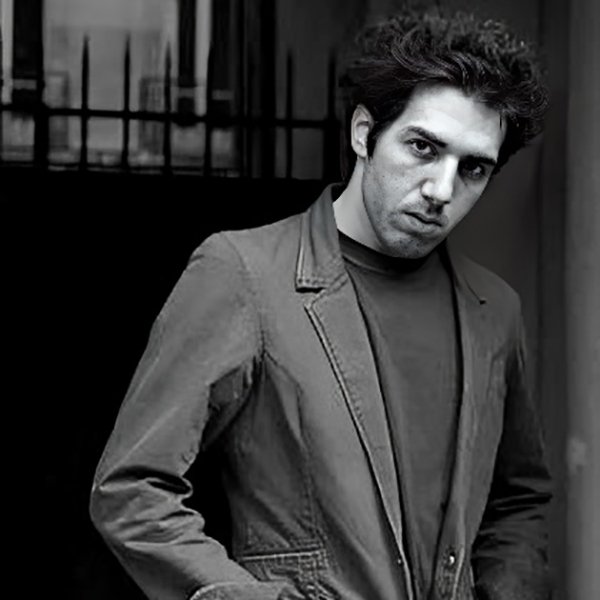

One is a poet enjoying late success as a novelist, the other a jazz singer caught in the Bombay grind. When Jeet Thayil and Suman Sridhar met in 2007, it didn’t take them long to decide form S/T, a UFO of a project in the Indian music scene, before releasing their first album in 2012. The colourful duo talked to Emaho about songwriting, politics, death, Bollywood slime, selling songs to the man, snakes and crosses, busking in the Paris metro, trading gender roles, playing to drunk Arabs on heroin…and much more.

Emaho : Jeet, you’re known mainly as a poet, more recently as a novelist, and also as a musician. What place does music occupy in your life?

I started on music around the same time as I started writing poetry. I was about 14 when I started playing the guitar and writing songs. For me, music is as important as writing. It was sometime around then that I also discovered drugs. It was the 1970s and the drugs we were doing at the time were “mind-expanding” drugs. Of course, now that seems like a complete cliché, and a way of putting a spiritual and intellectual gloss on something that is pretty stupid in many ways. But for me, that initial impulse to do something creative was very much tied to what was happening in the 70s, and with drugs. I started writing songs the minute I picked up the guitar. And yet, for many years, I didn’t play music, whereas there’s never been a time I haven’t written. I write every day. I don’t play guitar or write music every day.

Emaho : Have you played in many bands?

I’ve played in way too many bands. If I gave you a list of the names of the bands I’ve been in, it’ll give you an idea of how fucked up the Indian music scene was in the 70s, 80s and the 90s. Just the names of the bands will tell you everything.

Emaho : Suman, you grew up with Hindustani classical music, then studied western music in the US. You’re influenced by jazz; you’ve sung for Bollywood soundtracks and done ad jingles. Do these influences come through in S/T and in your music in general, not just in terms of musical sounds, but also work ethics and performance?

Definitely. Originally, I found it really difficult to do takes. I was the recording engineer as well as the artist. I found that very challenging, as I didn’t have any distance. I was driving myself nuts with the whole recording process. After doing session work for jingles and things like that, I became better at it. I learnt which take to trust and when to stop, some basic rules about recording. I learnt these things on the job, doing commercial work, and that really helped with the production part of S/T.

I must say that I got a bit of a culture shock when I started in the Indian music scene because the pop and rock scene was totally alien to me. I’m definitely the nerdy musician! Sinking my teeth into the material and the music is something I treasure, and that I’ve learnt from jazz.

Emaho : You’re obviously not one of those nerdy musicians when it comes to performing live. Where does that come from?

That’s something I learnt on the job. If you’d seen my first gig at Zenzi, you’d realize the distance I’ve travelled. The more you do it, the more it evolves. All the different parts of me—the actor, the poet and the lazy rock musician—have been integrated into the stage act.

Emaho : How would you compare S/T to your solo project?

There’s an obvious overlap because even with S/T there’s a lot that I bring. For example, there are, on the album, a number of songs that I was heavily involved in from start to finish, even though it was a largely collaborative effort.

My solo stuff is different from the old S/T, but then so is the new S/T. If you see us perform now, it’s totally different. The last tour we did was a lot more improvised, more mellow, less rock, more spoken word, more political.

My solo stuff is more political than S/T has ever been. I’m doing a cover of “Gay Maharashtra”, which talks about Bombay, post-Bal Thackeray’s death. There’s definitely a shift in my artistic journey in the sense that I’m not just interested in writing good songs. I want to integrate into the music another side of me—the academic mind, the anarchist who was visiting jails and doing civil rights work in the States. I want to connect all the dots.

Emaho : Jeet, I read that you chose the name S/T because you were afraid of another bad band name.

Truly. I just didn’t want to be in another band called Synthetic Frost or Atomic Forest or Cosmic Junk or Dr. Dong and the Wrinkled Scrotum.

Sridhar/Thayil – Psychoactivated

Emaho : Jeet, you went busking in the metro in Paris, back in the day. How was that? Would you say it’s a useful experience for a musician?

Super-useful. The thing about the French metro audience is that they know their shit. They’re not uneducated. Back then there were 7 or 8 guys doing a particular line. They knew each other, they were rivals, they were tough, very often there were fistfights. There were 7 stations between Les Halles and…I forget the other station…but you stayed within that circuit. And I always saw it as 7 stations of the Cross. I thought of it in very Christian terms. You had just enough time to do two and a half songs. I would play one very catchy kinda pop song of mine, one Dylan track and a blues song to which I made up lyrics as I went along. I would begin with my song, then do the blues song and halfway through the Dylan track we would get off the train. We made around 500 francs a day, and we didn’t even work all day. Some of these guys did it 9 to 5. I wasn’t disciplined enough; I just needed the money to buy alcohol. I would do it for about 2 hours.

The only reason we made money is because of the guy I worked with. He was this English punk who had been living in the streets of Paris for a few years. I’d start singing–he would wait for one verse, then go to the passengers, open up his little leather purse, stand in front of them and say, “Quelque chose pour la musique” (“a little something for the music”), until they put something in that purse. And he wasn’t asking a question. He was fucking demanding it! He wouldn’t move. What he did was probably more important than what I did. A lot of musicians in those times had to be fighters, and know how to use a knife and shit like that.

Emaho : What is your most memorable experience of playing live, both individually and in S/T?

The single most memorable experience was a New Year’s gig in this famous club in Bandra. We were told to turn our volume down because the diners couldn’t hear each other. We were basically competing with the clink of cutlery. I thought it was the worst gig I’d done in my life, but I was wrong.

We did this gig in a place called the Slip Disc in Colaba, which had been famous at one point because Jimmy Page and Robert Plant had performed there one night (for a bottle of whisky, as the legend goes). I played there with a trio. We did covers. One cover we did abysmally because all three musicians were on junk at the time. I remember we played Stevie Wonder’s ‘Superstition’ with an endless guitar solo. The club was frequented by drunk Arabs and hookers. At one point, this one Arab who was reeling across the floor, tripped on his robe, and fell onto the small stage. The drums went clattering into eight different corners of the bar. That was the end of our show for the night.

Emaho : S/T is quite an unusual and original outfit, especially in the context of the Indian music scene. Is there a clear, conscious vision behind it or did it develop organically?

Suman : In the beginning a lot of it was visual—the whole idea of snake and cross. We were into stripes and dots, fluorescent crosses. The visual images somehow seemed to tie in with the rest. I think it happened organically. Originally, I was the production head and it was Jeet who had the ideas, concepts and vision for S/T.

Jeet : Yeah, there was a vision right from the beginning. From the moment we started writing songs, we were also talking about what the band would be. Right from the name, to what we would bring individually to the band. It was more than just music; it was also theatre, poetry and performance. Also, the different genres that Suman brings with her: jazz, hindustani classical, opera. I listen to opera all the time. So we wrote an opera (Flying Wallahs). We would trade gender roles: she would wear men’s clothes. I would wear a skirt and makeup. At one point, we were both bald. It was great fun to play with all that. It was very exciting and I don’t think there was anyone else doing this at the time, certainly not in India.

Emaho : Most songs on STD don’t really have a hook or a chorus; there are no anthems as such. Do you consciously try to avoid using conventional structures, a formula if you will?

Suman : I just don’t have enough of a background in pop and rock music to even think of those forms as reference points. Jeet has more of that. Our music now is probably further away from what was on the album. For me, what we do live is way more exciting than how the album turned out. There’s a gap between what we wanted to put on the record and what ended up happening. Next, we’re thinking of just doing an EP—going in the studio and doing a multitrack. I’m excited to write new stuff; I have more clarity now.

Emaho : You say you see S/T more as a collaborative than a band, because you’ve done other projects together, like the Flying Wallahs opera. Has it been easy from the start collaborating together or was it a learning process of sorts?

Jeet : It clicked right away. Things are a bit different now because we live in different cities. Still, if you put Suman and me in a room together for a couple of days, we’ll come out with something. It’s always been the case.

Suman : Yeah, it was a natural process. Right from the beginning, we would talk to each other, throw one-liners at each other and the lyrics would follow.

Emaho : Do you have plans for another project together, apart from the band?

Suman : We did Art of Noise, which I really enjoyed. I want to bring that back; we only did it twice. It involved bringing musicians in to collaborate with us. We only met once to rehearse. It was deliberate. We played with the idea of sound and abstraction, not necessarily putting form and structure to everything.

In my solo work I’ve done collaborations with visual artists, and performance art pieces in collaboration with dancers and filmmakers. I did this thing at the Goethe Institute with some guys from Berlin where they staged a conference set in 2081. It was a coming together of music, theatre and art.

Emaho : Suman, you said in an interview that it was “only natural that a singer and a poet collaborate together”. One might think there could be creative tensions. Was it ever the case?

Suman : No, not at all. I have a poet hiding inside me and Jeet is a closet singer. Some part of him is the diva singer, the front woman.

Emaho : Precisely. Wouldn’t that create tension?

Suman : Yeah, it’s probably the same tension that creates those songs, so there you go!

Emaho : You were both in a relationship. When it ended, you kept the band going. This has happened to several groups in the past, with different results. In your case, was it difficult to keep the project afloat?

Jeet : The difficulty is logistical, the fact that we live in different cities and can’t spend much time together. When it comes to producing new music, you need to hang out in the same city, see each other regularly, jam regularly. We haven’t been able to do that. It’s been surprisingly easy to keep the working relationship going even as the personal relationship ended. And that’s rare.

Suman : It’s been difficult not so much because of the end of the relationship, but for other reasons, and that’s always been the case. The end of the relationship didn’t change that many things.

And if I have to say it, it’s Jeet’s writing. In fact, that’s always been a bit of a juggle right from the beginning. He’s been able to pull-off a double career, which is not something most people can do. We took a year off because he was on a book tour. We launched the album and then didn’t tour for a year. In the end, I think it’s kind of nice to keep your love life and your work separate.

Emaho : Was it easier once it ended?

Jeet : It some ways it was. Our disagreements now are purely to do with work. And disagreement is good because stuff comes out of it. Suman and I have ended up being closer in many ways after we split up. I think of her as family.

Emaho : Any advice to couples who play in bands together?

Jeet : Break up. Quickly. As soon as you can.

Suman : Think of yourself as your own person. Remember you came into this world alone and you’re going to the grave alone. It’s nice to keep some distance. I think Jeet and I have had a relatively smooth transition. We’ve managed to be good to each other.

Emaho : How have you guys rubbed off on each other while collaborating these last 5 years?

Jeet : I’ve become much more confident about my lack of technical finesse and theoretical knowledge. I’m completely self-taught. I took classical guitar lessons at 14, which taught me nothing. It did though give me a sense of ease with the strings and a feel for nylon-string guitar. Apart from that, I’m unlearnt; I’ve never been to music school. I don’t know anything about music. Yet I can write songs.

Working with Suman, I realised that theory, technique, classical knowledge and all that stuff you learn can actually come in the way of writing a song. Suman is a great musician, she’s a natural teacher, she knows musical theory, she’s almost pitch-perfect. But when it comes to songwriting, my chops are better than hers.

Suman : I’m more of a writer, more of a poet than I was before. I’m giving that side of me more room to grow. I’m writing and performing spoken word. I’m a sponge! I’ve definitely learned a lot when it comes to form and songwriting, and the simplicity of his melodies. Not just looking at arrangements or chops, but also giving room to the simplicity of melody.

Emaho : Would you say you are complementary?

Jeet : Totally. I think I taught her something as well. I taught her to write songs. I taught her to simplify. She learnt something from me that she hadn’t realised before, which is that you don’t need to bring all that stuff to the song. In fact, the less you bring, the better the song is. The problem with great musicians, like Suman, or other very good guitar players I know, is that sometimes they try to show off so much that the song sounds like shit. You want to hear a melody that grabs the heart.

Emaho : Jeet,you were a poet before you were a novelist or a musician, and you also do a lot of spoken word. You’ve described how writing a novel is a long process, which requires a 9 to 5 kind of discipline. Is writing and performing with S/T closer to doing spoken word or is it again a completely different process?

Jeet : It’s like writing a poem. S/T for me is a kind of release. It’s joyful activity, joyful noise. Whereas writing a novel is the opposite of joy. It’s drudgery, it’s hard work, it’s pain, it’s neurosis. Playing in S/T is the opposite of neurosis. It’s about releasing your demons.

Also, in a band you’re always working with someone else. So if you fail and have the worst gig, even then it’s not so bad because there’s someone to share your failure with. And you’re together during that. When you fail in writing a novel, it’s the loneliest thing in the world.

Emaho : But that hasn’t happened to you yet…

Jeet : It happens each time you are writing. The one I’m working on now…I’m filled with doubts.

Emaho : Your style of guitar is quite sparse and blues oriented. Your vocal style is closer to spoken word. Are their performers/vocalists/artists who have had a significant influence on the way you write music and perform live?

Jeet : My biggest influences have all been vocalists, from opera singers, to funk singers, to crooners. Maria Callas, James Brown, Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Bobby Darin—that’s what I always wanted to be. But I can’t sing. And I write songs that I can’t sing. I write songs with often devilishly complicated vocal lines; I know what they should sound like, but I can’t sing them the way they’re supposed to be sung. It’s a wound, a tragedy, a curse.

Emaho : What about you, Suman, is there a vocalist/performer who has had a significant impact on your vocal style or live performance?

Suman : Prince, Bessie Smith, my mother, Laura Claycomb.

Emaho : Jeet, the success of Narcopolis has brought you a lot of attention, most of it positive I would imagine, but it has also made darker parts of your past public, like the fact that you were a heroin addict. Though you in no way try to conceal this, do you sometimes feel it has become a kind of label that people stick on you?

Jeet : Definitely. Sometimes I want to say, dude, if you think this is a book about drugs, you haven’t read it! The drugs are just the frame. It’s really a book of thoughts, ideas, characters and stories. And yeah, the drugs are what links them. I guess the reason it happens is because it’s the first such novel in India—a literary novel that circles around the world of modern drugs. Palash Krishna Mehrotra has done it with his short stories, but this is the first full-length novel that deals with just that one thing: you know, serious drugs, heroin, opiates. It’s a new thing for India and I think that’s why people latch on to the druggy elements in it. And it’s okay.

Emaho : Many rock musicians and jazz musicians before them took heroin. Do you think it can have a positive impact on creativity, even though it is undeniably destructive?

Jeet : I know there have been musicians that it’s had a creative impact on. Like Miles Davis and Charlie Parker. They were producing astonishing music during the worst of their heroin days. Even someone like Kurt Cobain was writing the prettiest pop melodies at the height of his addiction. The opposite of what his life was at the time. These sweet fucking melodies. He would then try and make them dirty, trying to disguise what it actually was, you know, adding a lot of fuzz.

Emaho : Any particular song in mind?

Jeet : (Hums “Heart-shaped Box” from Nirvana’s In Utero). If you were to take “Heart-shaped Box” and give it to someone like Taylor Swift, they would make it into an AM chart hit. Because it’s a pretty catchy tune. What Kurt Cobain tried to do is disguise that with layers of heroin grime. Thing is, those exceptional musicians were able to do it; I never was. For me, heroin was the most unproductive thing on earth. All I could do on heroin was journalism.

Emaho : Jeet, your wife died in 2007, shortly after you had overcome your addiction. This was obviously a very difficult time for you. Did you at this point feel that you could slip back into drugs or, on the contrary, was your recent kicking of the habit a reason to march on?

Jeet : If I hadn’t kicked it when I did, if I had still been using it when my wife died, I might not have survived. When someone really close to you dies, you’re drawn to death. It’s so easy to go that way. Or you could go towards life. Some people go towards life in a more aggressive way than they have ever done. That’s what happened to me. I stopped wasting time. I felt the burden of my wife’s dreams and hopes. I felt I was carrying them with me.

Emaho : Did this event find an echo in your music?

Jeet : Of course. The entire Flying Wallahs opera is to do with the death of a spouse and the return of a ghost. A very angry, nasty ghost. Every line in that opera has to do with death. Narcopolis too is full of ghosts—people who die but do not leave. Their spirits stay, sometimes for the better but more often for the worse.

Emaho : Even though Jeet has moved to Delhi, you guys are a Bombay band. Jeet, you’ve said that the city hasn’t been the same since the 1992 riots and you seem somewhat disenchanted by it. Suman, you’ve lived and worked long enough in Bombay, and have seen Bollywood from the inside. Does the city still inspire you? Your music? Is it a love/hate relationship, like it often happens with big cities?

Jeet : It’s still an inspiration in music. One of the things Suman and I have been working on is to do with the riots and how Bombay has changed. The chorus goes “Boom town, boom town, where has your boom gone?” It’s to do with what 1992 did to the spirit of Bombay and that spirit will never come back. It will always be love/hate, because every time I step into Bombay I’m overcome with a feeling of belonging. I feel at home in Bombay in a way I never will in other cities. Certainly never in Delhi, ever. Or in New York. Hong Kong, maybe, but Bombay— that’s home.

Suman : It’s a love/hate thing for sure. One of the new spoken word pieces I’ve written was inspired by Narcopolis. Jeet might do a verse for it; it might be a new S/T song.

Bombay is the rat race taken to its extreme; the hustle is extremely dehumanising, more than most cities I’ve seen. I think it helps to get out, otherwise it’s kind of scary. And it’s gone from an open cosmopolitan city to a very policed, conservative city, It’s a much more divided city. When Bal Thackeray died, people were afraid of saying anything, even among liberal circles. But I guess there’s something about the city that keeps bringing you back, an addiction, as Jeet says.

Emaho : Suman, you’ve had a foot in Bollywood. What’s your take on it?

Suman : It’s pretty gross. I’m acting in a film right now, which is set in Bombay and explores the seamy side of glamour. It’s part documentary, part fiction. My life is fictionalised in the film. The film industry is unmanaged, ununionized, there’s no base pay for anything, and the casting-couch is a reality. It’s slimy. I think this is the generation that’s finally exploring new patrons for the arts. It’s happening slowly though.

Emaho : What do you think of the music scene in India, where there are more and more festivals and bands forming and performing?

Jeet : I think it’s a great thing. It’s wonderful that so many things in India are changing at last. It’s a very exciting time to be young in India. There are venues all over Delhi where a band can play. When I was playing music in India in the 1980s, you just had to play covers.

Suman : I hear of new bands everyday. There’s a lot of music happening through avenues like alcohol sponsorships, TV shows, MTV and tie-ups with embassies. It’s happening in a more sustainable way. At the same time, these festivals and corporate funding etc also make me nervous. It’s suddenly feasible to dream of being on MTV and that’s great, but can we make something original and exciting and authentic? Because these things are new here, a band can suddenly explode and have commercial success. We need to question what success or accomplishment means. I don’t want these things to become the goal.

The music industry has opened up to this country for the first time. It has become an aspiration for all of us. If it was all grassroots and DIY–like it was earlier– then your goals and ambitions would be different, right? There needs to be a marriage between the two. Let the industry not swallow up your vision, what you want to say. I think it’s great that we have all this money coming in; the challenge is to exploit that and not the other way around.

Emaho : Suman, you’ve said in a previous interview that in the Indian scene, everyone is trying to “Please the man”…

Suman : Until now, India has been completely under the radar. No one gave a fuck about Indian music, unless you were doing some tabla-sitar exotic thing. It’s the first time that contemporary Indian artists are getting attention and respect internationally and that’s a great thing. But just because all this has finally come here, I don’t want to act like a third-world artist. It’s like finally the scraps are being thrown at us and we have to go get them. I wouldn’t want to lose the drive to say what I really want to say, even if someone dangles the carrot of immediate success in front of my eyes.

Emaho : Even though you’ve both lived in India as well as abroad, you are very much an Indian band. Do you think it’s important for bands in India to have some “Indian content” or “Indian identity”, either in the themes or in the music? Do they need to draw from that specific environment and culture?

Suman : Yes, I would think so. If you’re making music here, it needs to speak to the people here. I think it’s one of the problems; we’ve been raised too much on Bob Dylan. You can’t live here and write a song about picket fences or jam tarts. There’s a post-colonial hangover in everything. That is the biggest challenge for the scene: to reclaim what is Indian or what that means. We need to reinvent that and not have to ape some western model of music or songwriting. I think there’s a new interest in folk music. When it comes to bands singing in English I haven’t seen it as much. Some of the older heavy-metal bands do it more maybe. I haven’t seen a lot of bands lately so I’m not really qualified to comment.

Jeet : I want to laugh when I hear bands singing in American and Jamaican accents. I mean, people, use your fucking Indian accents! That’s something Suman and I talked about from the beginning. She uses Tamil and Marathi. When we speak, we use our own voices. At this point in history, India is the future in many ways, Asia is the future. Why are we looking to America? It reveals a mentality where we always think we’re second best, not real, not authentic. The only way we can prove our authenticity is by speaking in a borrowed accent. It’s the sign of a backward culture. It shouldn’t be happening, especially now. I’m sure soon enough you’re gonna start hearing singers with fucking thick Indian accents. That’d be a beautiful thing.

Emaho : Whats the best thing about playing music in India?

Jeet : It’s a very exciting place to be in right now. Indian folk music has been brought into the mainstream. It’s no longer ‘fusion’ now—just music. A band like Hari and Sukhmani— I saw them at the Holi Cow Festival a few years ago. I was astonished by that girl, what the music sounds like. I can see that sort of thing clicking in a Berlin club, and it’s a totally Indian sound. I can imagine it sounding better, with a real band maybe, but I can hear the potential in it. We’re gonna be hearing more and more of that, coming from the weirdest corners of the country. Whereas sometimes, in a place like Rome for example, you feel like the music scene is stuck in one era, there’s nothing new.

Suman : There’s so much raw material to play with. Our tradition and culture is overwhelmingly rich. I’m excited to discover the “non-scene” within the scene and expanding the scene in that sense. Oh, and also the fact that we don’t need a fucking permit to play on the street! All you need to say is that it’s a wedding or Ganapati or something. We don’t have a policed state just yet so we might as well take advantage of that until it lasts.

Emaho : The worst thing?

Suman : It’s parochial and incestuous. We’re all in bed together. Event managers run a monopoly. There’s a prejudice in favour of dance music; there isn’t enough appreciation for live music. Since the music scene is linked with clubs and liquor companies, it’s connected only with nightlife. We also have a cattle and herd mentality in India. If somebody else says something’s good then it’s good, especially if the western world says so. That’s exactly what happened with Jeet’s book. This is always a challenge in India and I think it starts with our education system. When you ask a question you get yelled at.

Jeet : It’s the same as everywhere else: dealing with the crooked system, the management, all those suits. It’s the worst part. I wish there was some way to break that system, you know the suits that make money off us for doing fuck all. I wish there was a way to liquidate those fuckers, to eliminate and annihilate them. That would save us all a lot of time, money and headache. Actually, the word I was looking for is “exterminate”!

Emaho : You’ve said that you aren’t interested in corporate endorsement. Would you endorse a brand you like?

Jeet : Oh sure, and it only comes down to one thing: how much money they offer. All products are the same; they’re there to make money out of you. There’s no product that’s any more ethical than the next. For me, if they’re paying well enough, bring it on!

Suman : Did I say that? It’s strange to call it an independent music scene since everything is sponsored by something corporate. We’ve never made music for commercial purposes and the opportunity hasn’t come up either because I don’t think big brands want our music. But I’ve sung a jingle for Coca-Cola so I’ve sold my soul for sure!

Emaho : Do you see a difference between giving one of your songs to a commercial and writing a song for a commercial?

Suman : I don’t know if I would give an S/T song for an ad. That would be tricky.

Jeet : I wouldn’t write a song for a product but if someone wanted ‘The Drowning Song’ to sell skin-whitening products, then I’d say: go for it. I’d laugh while I watched it though.

Emaho : I forget who said that “Art only becomes significant when it is confronted with difficulties”. India is still a conservative country where censorship and taboos are much more present than in the west. Do you think that makes it more challenging but perhaps also more interesting for artists?

Suman : I think there’s a bigger responsibility, and more fodder for creation, but it’s also more challenging for this reason. In the absence of non-profit funding it becomes very difficult. We’ve been told directly not to perform spoken word. We’ve been censored. We’ve been told to “tone it down”. Whatever that means. But there are always things that need to be said that are not being said, and if the artist is not the voice of the community, I don’t know who is.

Jeet : I completely agree with whoever said that. Difficulty makes art happen; it makes art sharper. Then again, in India things are not as hard as they are in Pakistan, for example. Look at the writers in Pakistan right now, there are about 5 or 6 of them doing amazing work. They have so much at stake that they won’t write a lazy sentence. They’re not doing it just for fame or money. A lot of writers in India see writing as a way to be famous or to make money, and that’s not gonna happen. You get a feeling of irrelevance in the lines, the sentences. That being said, in India there are so still many things you can’t say, that if one were to explore these, one could use it in a creative and original way.

Emaho : Do you do that with S/T?

Jeet : Of course. Suman does it. We have a song in Marathi about Bombay. It says some uncomfortable truths. So far we haven’t had our limbs broken. But you never know.

Art & Culture Interviewed by Tony Guinard

Photographs by Asif Khan