Australia –

With our growing dependency on genetic manipulation and bioengineering we might be hesitant to ask when is it too much? Australian artist Patricia Piccinini walks this fine line with her unsettling hyper-realistic sculptures. From sci-fi to mythology, Piccinini talks about her world of creatures and her role as benevolent creator.

Emaho : You weren’t always a sculptor, though your hyper-realistic sculptures are some of your most famous work. What drew you to working three-dimensionally?

In the mid-1990s, when I left art school, I was primarily working in painting and drawing, but I was very dissatisfied with the way the paintings communicated the ideas I was interested in discussing. There seemed to be a disconnect between the medium and the content. So while I continued to draw, I also started to work with photography. Once I had started with that I realized that I didn’t need to be constrained by the limits of my own skills, so long as I could work with people. My photography had often included creatures that I incorporated digitally, and I started to think that it might be interesting try to bring them to life three dimensionally. I really like the emotional immediacy that hyper-real figuration gives the work. However, it still always starts with drawing. I feel that my drawing is actually the core of my practice, where I develop ideas before making a decision about how they should end up as objects.

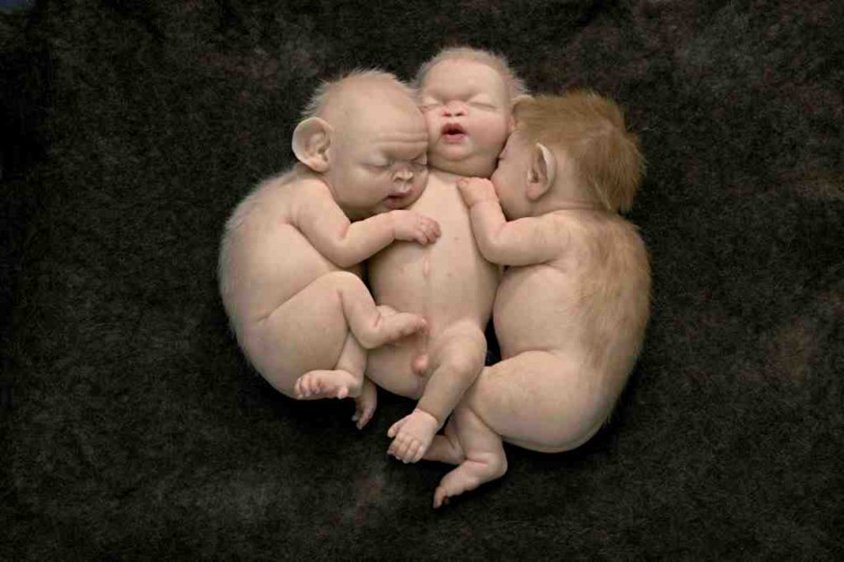

Litters

Emaho : Your work is cohesive because it seems to revolve around a central theme –which I take to be the intersection between technology and the natural world. Has your idea evolved over the years?

I think so. When I look back at early works I often feel very conflicted. On the one hand I’m surprised at how close they are conceptually to what I still do, but on the other they seem a bit naive. Which is okay I guess as dissatisfaction with your own work is often what drives you to try to make it better. Anyway, in thinking about the evolution of my ideas over time, what strikes me is that the focus has shifted from the ‘political’ to the ‘personal’ in many respects. In my early work I was much more interested in the media and biotechnology companies and the like, from the point of view of social implications for example. In my recent work, my interest is more in the emotional context, in empathy and the relationships between the creatures and viewer on that level. I am also now more interested in the natural world than in biotechnology, and I see my world as more mythical or dreamlike than sci-fi.

Doubting Thomas

Emaho : Many of your monstrous creatures are paired with human sculptures, especially children. What effect do you intend to create with this unsettling dichotomy?

For one thing, children directly express the idea of genetics – both natural and artificial – but beyond that they also imply the responsibilities that a creator has to their creations. The innocence and vulnerability of children is powerfully emotive and evokes empathy – their presence softens the hardness of some of the more difficult ideas. The children in my works are young enough to accept the strangeness and difference of my world without difficulty, and they hint at the speed at which the extraordinary becomes commonplace in contemporary society. For me, the clear emotional bonds that connect the children and the creatures in my work are simultaneously optimistic and disturbing. Their closeness is both moving and unsettling.

Long Awaited

Emaho : Do you see your creatures as sending a warning to us about the unintended effects of how we engineer nature?

I don’t really see my work in such definite terms. For a start I don’t think we can think in those terms. It’s like rabbits. Who doesn’t like a cute little bunny rabbit? Yet in Australia they are a massive environmental problem, a real threat to native landscapes and animal populations. The problem is not bunnies per se; it is what we have done with them. In their place they are wonderful. I don’t feel these questions have simple answers, or that I am the one who should attempt to answer them. What I am interested in is getting people to have the discussions, but in a way that doesn’t allow an easy good/bad type answer. This is a process that we will need to negotiate at every turn.

The Coup

Emaho : You wrote in your artist’s statement for In Another Life that “there is no question as to whether there will be undesired outcomes; my interest is in whether we will be able to love them.” Would you describe your creatures as loveable?

Absolutely! One thing I am absolutely sure of is that I am a huge fan of diversity, and that I have enormous affection for every creature I’ve ever created. I’m not saying that I think that they’re perfect or an improvement on nature but I think they have a certain beauty. I am very interested in the creator’s responsibility towards what they create. I guess I do understand some people’s reactions to them, but in a way I am always challenging those people to see what I see in those creatures. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a very important book for me. As I see it, it is not so much a parable about hubris but about parenting. The tragedy stems from Frankenstein’s disappointment with his creation and his refusal to nurture it.

The Carrier

Emaho : There is a certain drama in your gallery installation at Arter in Istanbul in that your creatures envelop the space. Is it your desire to have people see your work in a setting that becomes its own world, rather than each piece in isolation?

Certainly. I see all of my works as coming from the same place. It is a sort of parallel world that is very similar to ours but not quite the same. While some works have closer connections than others, I don’t think any of them are mutually exclusive. This is often difficult for viewers who are conditioned to group works and therefore try to separate my silicone sculptures from my fiberglass ones. I was really happy with the installation at Arter because the space and installation allowed me to really make that point and create that other world that isn’t just more artwork in an art gallery.

Art & Culture Interviewed by Hilary Devaney

Art Works by Patricia Piccinini