Emaho: Can you share some memories from your early life that influenced your journey into the world of design?

Rooshad: As children, my brother and I often accompanied our father to his office, and that early exposure to the field of architecture sparked a genuine interest in both of us. It became almost inevitable that we’d follow the same professional path, so much so that our parents actually hoped that one of us might choose a different direction!

Emaho: What first inspired you to pursue architecture and design professionally?

Rooshad: Design has always felt like a natural choice to me. I grew up in a family of designers — my father, brother, and sister-in-law are all architects, and my mother is an interior designer — so creativity was a part of daily life. And being introduced to the field at such an early age instilled a deep awareness of my surroundings. That foundation was strengthened by travel opportunities while growing up— visiting museums, exhibitions and galleries — which further shaped the way I observe and think about design.

Emaho: How did your education at Harvard and early career experiences shape your creative philosophy and approach?

Rooshad: I think the school environment encourages you to be exploratory — to back up your inspiration with research, and to see craft and technology as part of the same conversation. I was privileged also, to gain work experience at the offices of OMA/Rex and Zaha Hadid in New York and London respectively, while simultaneously pursuing my education.

Emaho: What, in your opinion, defines “good design”? Are there key principles you always adhere to in your practice?

Rooshad: When it comes to what constitutes ‘good’ design, I believe that it must adequately address both function and requirement. Aesthetics — balancing colour and proportion, or pushing the boundaries of a technique — are important, but they aren’t enough on their own. Ultimately, good design should offer an intelligent, well-considered solution rooted in careful evaluation.

Emaho: Indian artisans and traditional crafts play a big role in your work. How do you integrate these elements into contemporary projects?

Rooshad: The preservation of Indian craftsmanship and its integration into today’s design language are at the very core of my work philosophy. As a result, the studio’s association with artisans and their centuries-old techniques has naturally taken on its own trajectory. We are continuously testing the limits of craft, looking for ways to make it resonate within a contemporary aesthetic. Growth and evolution are the inevitable outcome of a collaboration between tradition and innovation.

Emaho: As you see it, what does the future look like for design and architecture in India?

Rooshad: Over the past decade, there has been a clear evolution within the market and in consumer attitudes. While it may still be early compared to international standards, clients today are far more willing to take creative risks, and that openness is shaping a much more dynamic design landscape within the country. We are also seeing a remarkable rise in global appreciation for Indian artists and brands, which signals a very encouraging shift.

Emaho: You’re credited for pushing boundaries in architecture. What motivates you to go beyond traditional forms and concepts?

Rooshad: My first job was at OMA/Rex under Rem Koolhaas, and the experience really stayed with me. It was a place where the ordinary and the mundane were always challenged, and the brief itself was unfailingly interrogated. I was there for only a year, but that methodology is ingrained in the way that I function and lead my practice. Every time we approach a particular project, it’s always about finding clever solutions, reinterpreting a brief and allowing us to think more conceptually, as against having a prescribed aesthetic for each project.

Emaho: Can you tell us about a project where breaking architectural norms led to unexpected or breakthrough results?

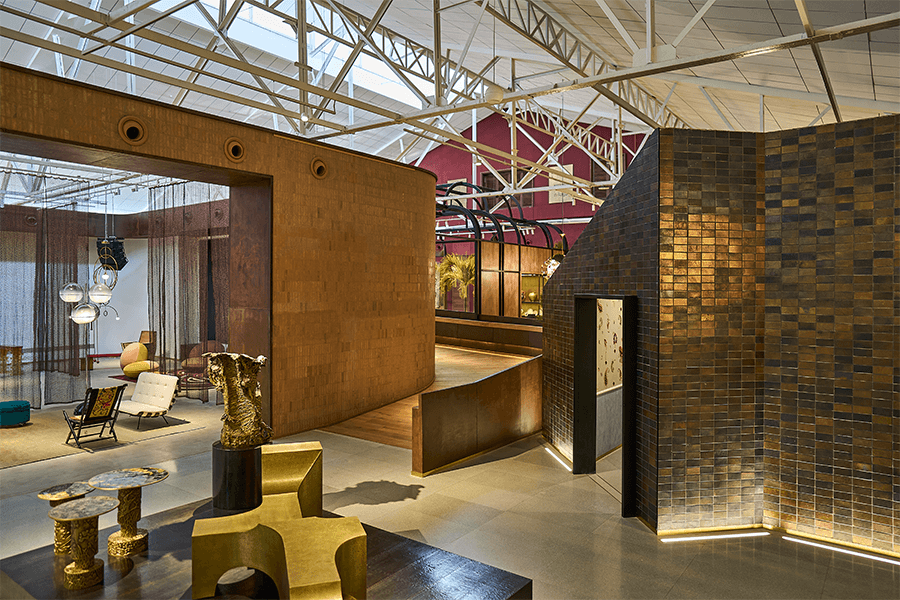

Rooshad: In March this year, we unveiled Nilaya Anthology by Asian Paints in Mumbai, a design gallery-cum-retail destination spanning 100,000 square feet. The straightforward approach would have been to just divide the entirety of the space and assign each of the several sections its own area, but we went about things very differently. The site comprises two distinct structures — a 40,000-square-foot warehouse with a soaring double-height ceiling and pitched roof, and a ground-plus-one building spread across approximately 55,000 square feet. The ramp that links these two buildings became this key gesture that keeps everything connected. The whole space is very open, so you get this sense of separation without putting up actual partitions. There’s a transparency and a freedom in how you move through it; definitely not a conventional way to divide any space, but it felt right for the project.

Emaho: What inspired you to develop your own furniture collection, and what sets it apart in terms of materials, techniques, or aesthetics?

Rooshad: There was never an agenda to set up a furniture division within the practice as such; it stemmed organically from our research into craft and material. It was always about pushing the boundaries of traditional techniques, making them more relevant, seeing how we can sustain them. That process naturally brought a certain rigour: questioning how certain objects are usually produced, stretching what a material can do, and slowly building larger pieces, collections and bespoke items for our interiors. I like staying with the same crafts and materials and seeing how far we can take each one, rather than switching to something new every season. We might introduce new techniques, but we never abandon the ones we’ve developed or the artisans we collaborate with. In its own way, that continuity also helps sustain the craft.

Emaho: Your furniture often collaborates with contemporary artists. How did these artistic partnerships come about, and what do they add to the pieces? Whose your favourite artist for inspiration ?

Rooshad: Collaborations initially commenced in 2019 with The Gyaan Project, a charity-driven design initiative that saw the work of renowned artists, architects and designers executed by traditional Indian artisans; the proceeds helped fund education-focused charities. I wanted to bring together a set of strong minds who could really explore print in intricate, nuanced ways, because it’s not a medium I consider among my stronger suits. Then, in the years post Gyaan, opportunities to work with artists like Tanya Goel arose. I find collaborating with individuals who have a novel perspective and methodology refreshing.

As for inspiration, I think currently that would be T. Venkanna, who we have also had the pleasure of collaborating with. He’s one of today’s most prolific artists, working across a variety of mediums — print-making, oil, charcoal, ink…He’s able to engage with any material he turns his attention to, be it embroidery that he produced at the Kalhath Institute or our own INpLAY collection. He understands technique and presents works that really understand the material employed successfully.

Emaho: Sustainability and slow design are often highlighted in your practice. How do you bring these values to your daily studio work and finished projects?

Rooshad: I have always prioritised quality over time. In an age obsessed with instant gratification, I want to return to the days when meticulous, hour-intensive craftsmanship defined true excellence. That, to me, is the essence of real luxury.

Emaho: For young designers in India, what advice would you give about staying innovative while respecting local traditions and craftsmanship?Where do you think the design scene in India is heading?

Rooshad: India has a wealth of artisans and craftsmanship to offer, which poses an advantage to every practicing designer within the country. Don’t seek to imitate anyone; make it your own. Design has to come from a genuine creative impulse — if the passion isn’t there, the work will feel hollow, and so will your journey. And it’s an intensely competitive field, so finding your footing can take time, sometimes years.