Bhutan –

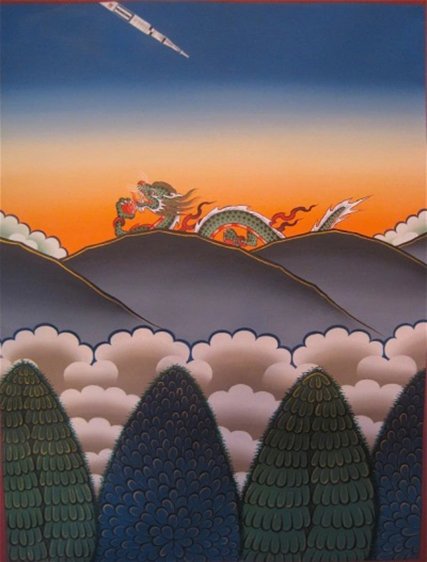

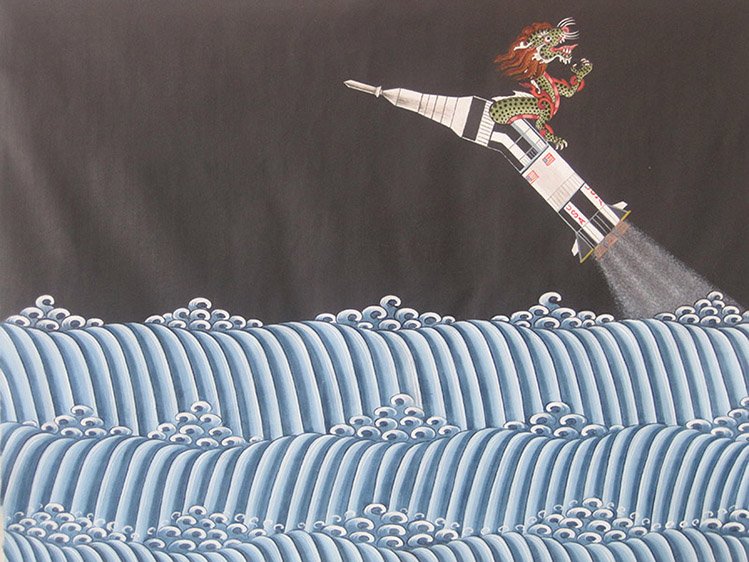

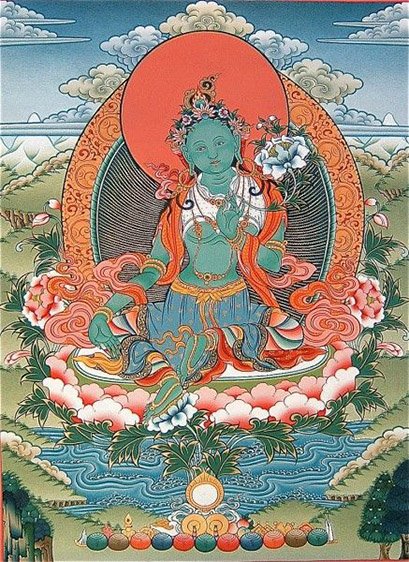

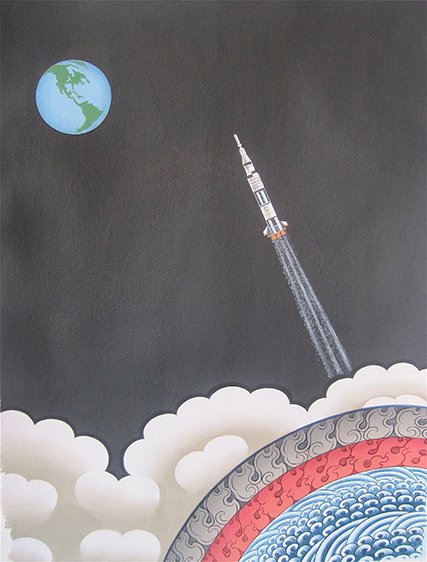

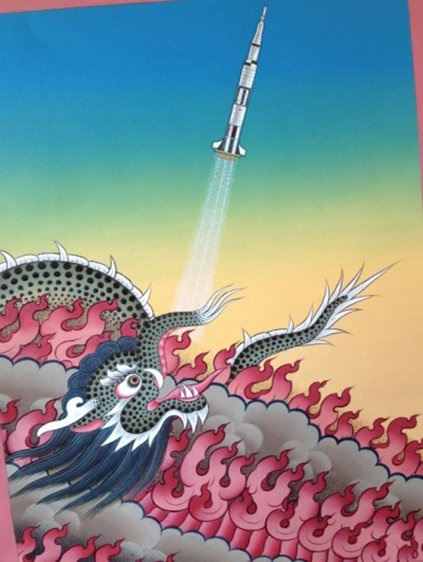

Bhutanese ‘‘thangka’’ painter Phurba Namgay has developed a cutting edge new style of Bhutanese art: a fusion of classical East and contemporary West. The new pieces combine Buddhist iconography and mythological creatures such as idealized dragons, tigers, snow lions, phalluses, lotuses and Buddhist demons with pedestrian road signs of the West. The outcome is enchanted, mysterious and whimsical images that may be read allegorically or literally. Namgay creates wall paintings in a method similar to painting frescos; he also paints on large pieces of canvas that are pieced together and attached to temple walls like wallpaper. In his new paintings describes his journey from the Himalayas to the West.

Emaho : At the age of 13 you started formal studies of Bhutanese painting at the government’s school of traditional arts in Thimphu. What has the journey been like since then for you as a painter from Bhutan?

After I finished studying at the school I apprenticed with a master painter and painted temples all over Bhutan for quite a few years. Then I returned to the traditional art school to teach. I worked there for about eight years then I retired and started painting on my own. In 2008 I went to the U.S. and painted there and studied Western art. I really like the American and British photorealists, and so I focused on painting that way. I feel like I’ve had a couple of lives as a painter already, traditional ‘‘thangka’’ painter and now Western art. It’s great do both because each style enhances the other.

© Phurba Namgay

Emaho : What you paint is Buddhist art. Is religious art sought by Buddhists only or does your artwork have a universal appeal?

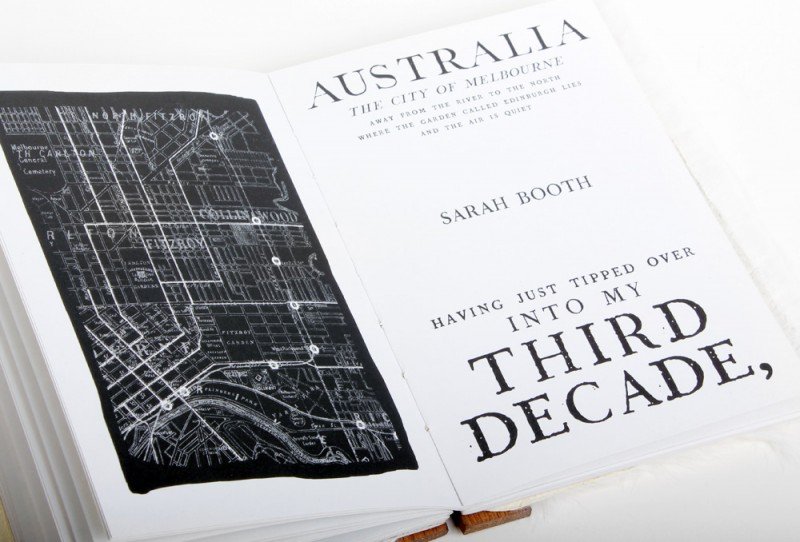

That’s an interesting question. I do commissions for Buddhists and I also sell traditional Buddhist art to non Buddhists who just like the images of the ‘thangka’s’ and ‘mandalas’. It’s probably about half and half. A lot of people like Bhutan or my wife’s book and they are drawn to my art. It goes the other way, too. They see my art and become interested in the country.

Emaho : Of late you’ve been working on merging traditional Buddhist art with Western forms of art; in what ways is it helping you widen your horizon as an artist?

My wife says my traditional ‘‘thangka’s’ are getting better since I’ve started doing more of the Western art in between. She says there’s more depth to my images. The sense of exploration I get from doing the photorealist pieces and the creative kick I get from doing the rocket pieces is energizing. There is some creativity in the ‘thangka’ art, but I’m not looking for an original point of view when I paint it, and I’m not “in” it in the sense of expressing myself and my feelings. It’s a type of meditation, an act of piety for me. But contemporary art is the opposite. I am seeking an original point of view, and it is all me. It’s about balancing both and that gives me a lot of enjoyment.

© Phurba Namgay

Emaho : These ‘thangkas’ that you paint are actually scrolls made to be rolled and unrolled for hundreds of years, so it’s important the paint doesn’t crack. How do you make the canvas then and what measures do you take? Also please elaborate on the importance of ‘thangkas‘ in Buddhist/Bhutanese Art?

For a long time at the painting school I went to, we learnt the process of perfectly applying calcium chalk and gum to cloth and then rubbing it with a smooth stone. We do this over and over again to make the surface smooth and if we do it right then the paint won’t crack when the ‘thangka’ is rolled and unrolled for hundreds of years. We also have to apply very thin and smooth paint for the images. That’s why we apply paint over and over, building it up instead of one time application. The ‘thangka’ artists of Bhutan are very important and ‘thangkas’ are still commissioned for births, deaths, marriages and other events. The images of the deities we paint are the most important thing.Traditionally we don’t even sign our ‘thangka’ art. But I do now since my work is collectible and the galleries that represent me made it clear that I should sign.

Emaho : Your paintings of the Buddhist ‘mandala’ are so intricate. I’m sure along with skill you require a lot of patience also. What sort of brushes do you use to paint so delicately?

Traditionally, Bhutanese ‘thangka’ painters make their own brushes and I do the same. I use our cat’s hair but the summer hair from a cow’s ear also makes a good brush. These are very small brushes with only a few hair strands to do fine lines. One of the first things we learn in school is how to make brushes, prepare canvas and make paints. I also buy brushes from Old Delhi when we’re there and I get them from the U.S. when I travel there. That’s a lot easier!

© Phurba Namgay

Emaho : Who are these characters Tsheringma and Vajrapani that you paint? What other characters from Tantric Buddhism are you painting and what are their contexts in the history of this practice?

Tsheringma is for “Long Life” and is a mountain guardian. Vajrapani is a powerful protector. Their images are seen all over Bhutan. There are hundreds of deities, dakinis, teachers and lamas that we paint images of in Bhutan. The history goes back to the 8th century when Guru Rinpoche, Padmasambavha, brought Buddhism to Bhutan via Tibet. Some of the Buddhist deities have become friends with the Bon that predated Buddhism here. So it’s a good mix.

Emaho : What are your views on the prospect of art in Bhutan, in general?

I think art in Bhutan is about to take off—the traditional painters I know are interested in learning more about contemporary art, and they are talented, and now we have a lot of opportunities to travel and look at it and study it. We can see it on TV and the Internet. Art in India is evolving, it’s getting very interesting and we look at it. I think it’s a natural progression that as Bhutan moves to democracy and things change, we will start to express more things through art. It’s the way of the world. What I hope is that we keep our traditional art but expand our horizons and also do contemporary art. That’s what I try to do.

© Phurba Namgay

Emaho : What about your ‘Abbey Road Snow Lion’ painting? It is way different from your usual traditional painting of Buddhist art.

I learned about zebra crossings or cross walks in the U.S. because we didn’t have them in Bhutan. Then I went home and painted a tiger on a zebra crossing. My wife showed me The Beatles’ Abbey Road album cover with the four of them on the zebra crossing, so I painted a Snow Lion on a zebra crossing as homage to that album cover. I listened to the album while I painted it. I was really into doing signs for a while.

You believe in signs – you read into them and incorporate them in your paintings. Each of these motifs in your paintings has a hidden meaning. Is this a part of a philosophy that you follow? Explain to us the connotation of some of your motifs – lotus, dragons, rockets, and the likes.

The truth isn’t as exotic as you describe it, but it’s kind of interesting. I spent some time in the U.S. and at one point I had to study to get a driver’s license. I had a hard time because I couldn’t see the signs along the road in the U.S. That is, I didn’t know what to look for. There aren’t many signs driving in Bhutan—it’s just one big long curvy road through the mountains. You’re on your own and there aren’t many cars. But in the U.S. there are signs everywhere so it was quite difficult. I kept running stop signs. Anyway, I started thinking about how in Bhutan we don’t have road signs but we have lots of signs—dragons, Buddha, all the iconography we paint on the buildings—it all means something. I started thinking about that and also painting that. I responded as an artist I think and I started incorporating the American and Bhutanese signs into my art.

© Phurba Namgay

In ‘Manjushri with Green Lights’ you painted traffic signals that you saw in your trip to America, in another you have painted a Starbucks coffee mug. In your travels abroad for your art showcases these things seem to leave a mark on you and your art.

Yes, I think I just started embracing that contemporary art thing—the idea that anything can be art. Anything is part of your personal expression if you feel it. I got addicted to Starbuck’s Verona while I was in the U.S. I’d never had much coffee. But it really gets me going.

Emaho : What is your fixation with rockets about? They can be spotted in many of your recent works. Is it about a desire to break away from the shackles of this world and going far away?

When I was a kid in Bhutan we heard about the Americans walking on the moon. My mother didn’t believe it. So for us rockets were as mythological as dragons are to people in the West.

I visited the Smithsonian, and I went to the Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. I really like rockets. As part of my personal mythology I’d say sometimes, especially in the U.S., I feel like I’m going somewhere really fast, I’m isolated, and I have no idea where I am. It must be a bit like being in a rocket. I like that idea, of breaking away from the shackles. But for me it was more like a forced march. It was about being the only Bhutanese in a Western society. I think it’s a universal feeling. You can be in a room full of people you know and love and be isolated. In the rocket paintings I try to be whimsical and fun but also convey that isolation. I like thinking about opposites.

© Phurba Namgay

Emaho : Your hyperrealist and photorealist styles of paintings are impeccable, eg the ‘Dopchu’. How did you achieve that?

I studied the works of Richard Estes, tried getting to know John Baeder, Ralph Goins, and other American photorealists and their paintings better. But at the end of the day, practice, practice, practice is all that helps to achieve perfection. I paint all the time.

Emaho : Your wife Linda York Leaming is the author of ‘Married To Bhutan – How One Woman Got Lost. Said ‘I Do’ And Found Bliss.’ She did not only fall in love with you, but also with Bhutan and its philosophies, what’s the story? Do you never think of moving out of Bhutan, like many other artists, to more profitable locations for your respective arts?

She met some Bhutanese in New York in the early 1990s and became friends and then she traveled to Bhutan. She had been living in Bhutan for a few years when we met.

So I think she fell in love with Bhutan and then she fell in love with me. We taught together for a while. Now we spend time in the U.S. and Bhutan. She’s working on her second book. I’m painting some commissions. It’s really good for my art and her books to be over there so we split our time. But we both prefer the laid back life in Bhutan. The more I travel around the more I want to be here in the mountains. There’s really no other place like it on the face of the earth.

© Phurba Namgay

Art & Culture Interviewed by Raksha Bihani