Gerardo you reached your last edition as General Curator of PhotoEspaña. How was your overall experience?

When Claude Bussac asked me to curate the festival in 2010, I was a little bit concerned, because she was talking about a three-year engagement. So I said, oh God, this is like marriage. This is not a one-night stand at all. If you are going to get married, you have to think about it very carefully! What if I don’t get along with the team? I don’t know the situation. This is a huge festival, a very complex one. I thought a lot about it and I finally said ‘yes’. I have to say now that three years have passed quite fast, actually my experience has been a very positive one. I learned a lot about photography, because I am not a photography expert as such. Of course, I know about photography, but I am more focused on photography as a part of contemporary art. I learned a lot about Spain and I had a very good working experience with the PhotoEspaña team, which is very professional, very well-organised, so much so that I thought I was back working in New York! These guys answer every email and work very efficiently. Also, I have to say that at no point did I receive any pressure from the organisers. I worked in a complete state of freedom.

© Fernando Brito. From the series ‘Your steps were lost with the Landscape’

Did you decide the theme autonomously or is there a panel where you discuss possible themes and then make a decision?

I decided completely by myself, that was my job actually. They call it Comisario General, which could be translated as General Curator, but it also means Artistic Director, as I took all the artistic decisions by myself, of course getting advice from people around the world. I established the three themes from the very beginning because that gave me the possibility to work with different degrees of concentration. One challenge that this festival has is that you a have a very short period of time to organise it. And there’s not only the pressure of the festival itself, but also the pressure of artists, collections, and institutions, as they have other engagements and they need to be contacted well in advance.

Fulvio Roiter, ‘Miniera di zolfo’, Sicilia, 1953. © CNAP

Why did you choose this particular theme, Body. Eros and Politics? Did you feel that it was a bit under-explored? Also, I would like to ask you: what does it mean for you the Body. Eros and Politics?

It is quite difficult to organise a festival that has had 14 previous editions, many of the outstanding themes have already been covered, so there’s not much room for you to choose. However, to my surprise, I discovered that two fields that have been with photography since its inception hadn’t been addressed yet, namely the face, portraiture and the body. Since the very beginning, photography has been dealing with the body, even the pornographic body. So I thought that I could design a thematic circle beginning with the face and ending with the body, but at the same time trying to confront the stereotypes about the face as a sort of window to the human soul, and the body as the field of the organic, of the erotic, of nature in the human being. This as opposed to culture, that would be identified with the face. I wanted to confront those stereotypes and try to look at the face not simply as portraiture, but more as a way for artists to construct their artistic discourses and communicate them. I did the same this year with the body: it’s not the nude as a genre, it’s more a mean for the artist to explore and to tackle a discourse in very different ways, a territory. And in between I had my second edition, which was about the context of globalisation, so it was more about social and cultural issues, a topic that I have been writing on as a theorist. What I tried with the body was to show all the aspects of such a vast theme. I wanted to prepare a festival where the viewer would be exposed to eroticism but also violence against the body, the body as a gender affirmation, the political body, the cultural body, the body that is covered, like in the case of Shirin Neshat, who reflects on the forbidden body of the Muslim woman.

Shirin Neshat, Serie Éxtasis, 1999. Foto Larry Barnes Courtesy Jérôme de Loirmont, Paris. © Shirin Neshat

I have seen a few examples of male bodies, like the famous photograph by Fulvio Roiter of naked miners at work, in the exhibition ‘Savoir c’est pouvoir’ from the Collection of the French Centre Nationale des Arts Plastiques, and the series ‘Desvestidas’ by Luis Arturo Aguirre in the exhibition ‘(Re)presentaions. Latin American Contemporary Photography’. However, predominant attention has been paid to the female body in the festival. Do you think that with the term ‘body’ we automatically think about a female body? How did you subvert this stereotype in the festival?

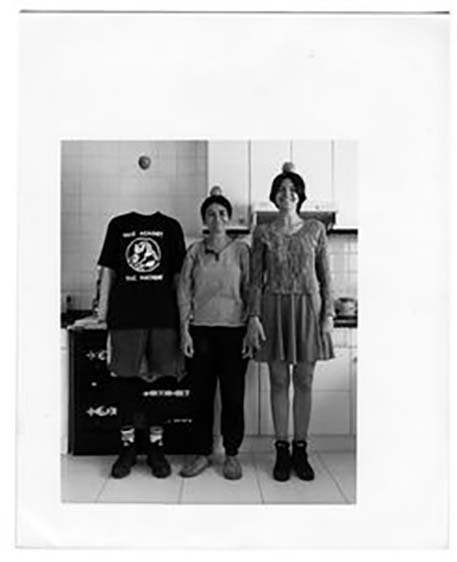

Yes, indeed, very much so. The way in which I phrased the theme was ‘Body. Eros and Politics’. Perhaps I should have titled it ‘Eros and Ares’, the god of war, to underline my intention to show the body as a battlefield. If you look at the Circulo de Bellas Artes where we have the thicker concentration of exhibitions, you will see a sort of synthesis of the festival in general. There you have the exhibition ‘He, She, It. Dialogues between Edward Weston and Harry Callaham’, whose photographs are the epitome of the male gaze on the female body, but also you find the female gaze on her own body in the show ‘WOMAN. The Feminist Avant-Garde from the 1970s’, as well as the work of Fernando Brito, ‘Your Steps Were Lost With The Landscape’, a series on the dead male body as a result of violence in Mexico. There is also the case of Zbigniew Dłubak, who works with female nudes not from the point of view of a traditional male gaze, but rather of a gaze which looks for structures, patterns in the body with a geometrical and abstract approach.

Zbigniew Dłubak, Untitled. From the series ‘Gesticulations’, 1970-1978. © Archeology of Photography Fundation / A. Dłubak

How does it work with the external curators? Do you appoint them and then you discuss which artists to involve and how to design the installation, or are they free to suggest their own ideas?

Let’s say that there are two different lines of work. In some cases I appoint them, I ask a colleague to curate a specific exhibition of the festival. That’s the case for example with Laura González Flores. I asked her to curate a solo show of Edward Weston within the thematic framework of the festival and then she came back to me with a different idea, to show Weston in dialogue with Harry Callahan, because she wanted to explore the relationship between them and their models and their different gazes. I thought it was a fantastic idea. She organised the show in dialogue with me but she took the final decisions about everything. So that’s one scenario. The other one is what I call ‘curating curators’, where I ask a curator whose work I admire, and that I trust, to conceive and propose me something within the general thematic framework. In this case the curator comes up with his or her own idea for the show.

Harry Callahan, Eleanor, Chicago, 1947. Collection Centre for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York © The Estate of Harry Callahan

Is that the case of Emmet Gowin’s show curated by Carlos Gollonet at Fundación Mapfre?

Yes. It is very important to underline that PhotoEspaña is a huge constellation of exhibitions and events, which implies a very difficult task for the General Curator: to find venues. When Carlos Gollonet told me his idea of putting together a major retrospective of Gowin’s work, probably his most comprehensive exhibition to date, I was more than happy.And it adds a further layer of dialogue to the Weston and Callahan’s show, as some of Gowin’s photographs, from his more recent series ‘Mariposas Nocturnas – Edith in Panama’ recall Callahan’s ‘Eleanor, Chicago’, 1954.

Callahan was Gowin’s teacher and a deep influence on his work. In the beginning, Laura González Flores wanted to include Gowin in Weston & Callahan’s exhibition and I had to tell her that we were already having a show on Gowin. There is a very interesting triangle between the three photographers, which came out as a positive coincidence.

Harry Callahan ‘Eleanor, Chicago’, 1954. Collection Centre for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York © The Estate of Harry Callahan

Emmet Gowin ‘Edith in Panama: Predation of the Leaf’ from the series ‘Mariposas Nocturnas – Edith in Panama’. Courtesy Pace/MacGill, New York. © Emmet Gowin

What about the exhibition ‘WOMAN. The Feminist Avant-Garde from the 1970s. Works from the SAMMLUNG VERBUND, Vienna’, which I found fascinating (and I hope it will come to London soon!)? The show was in Rome in 2010. Is it the same exhibition?

The show was reshaped including the new acquisitions of the SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, which focuses on the feminist art movement of the 1970s and on the innovation it brought to contemporary art. That’s why the curator, Gabriele Schor, titled it the ‘feminist avant-garde’. We adapted the exhibition to the needs of PhotoEspaña 2013. To give you an example I asked the curator, Gabriele Schor, to reduce the section dedicated to Cindy Sherman because we already had a show of her work back in 2011. There were many changes.

Renate Bertlmann, Schwangere Braut im Rollstuhl / Pregnant Bride in the Wheelchair, 1978, Four b&w photographs on barite paper. © Renate Bertlmann / SAMMLUNG VERBUND, Vienna

It was so much needed to finally see Martha Rosler’s video ‘Semiotics of the Kitchen’ (1975) on a proper screen!

That piece is a classic! I mean, it is a fantastic show. It perfectly combines lesser-known artists with masterpieces of the 1970s and the curation is extremely good. The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection is so great precisely because its curator has a vision. That’s why I approached them.‘Semiotics of the Kitchen’ , Martha Rosler, 1975

I would like to move on to Latin American photography. Do you think it is underrepresented in the European contemporary photographic realm and what has PhotoEspaña done to fill this gap?

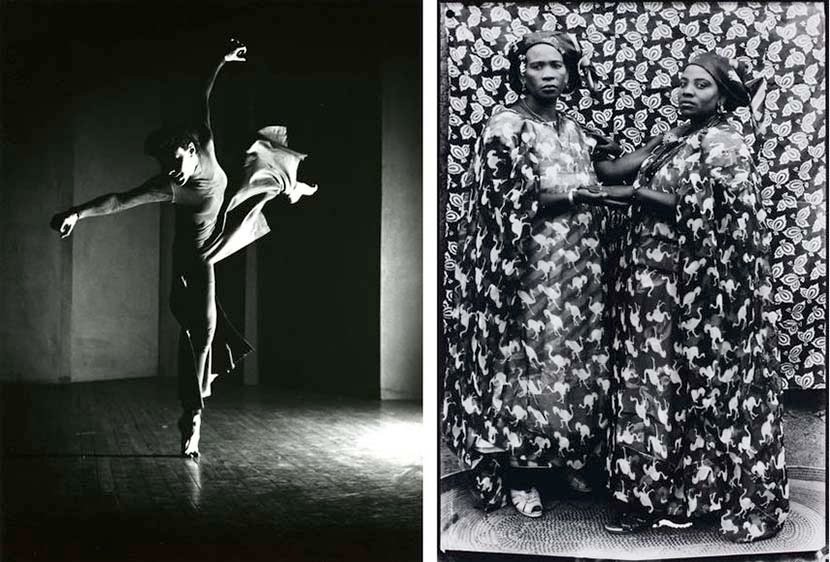

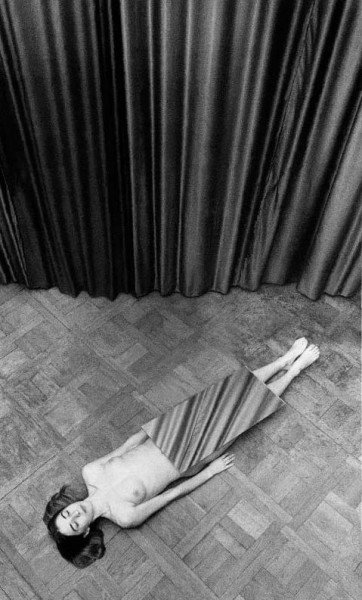

To a certain level I agree with you, it is underrepresented in Europe. But then when I looked back at all the previous editions of the festival I realised how Latin America was actually always covered by PhotoEspaña, together with Western Europe and North America. If we wanted to be truly international we had to look East and include more Asian and Eastern European photography. So I focused more on them than Latin America, which in the case of this festival was well represented. I travelled a lot to meet and invite Chinese, Japanese, South Korean and Indian curators to participate to the festival. For example we had the Raqs media collective curating an online exhibition last year. This year we have a strong Eastern European presence, with three shows that I really like: the aforementioned Polish Zbigniew Dłubak, the Modernist Nudes of the Czech František Drtikol, and the Lithuanian Violeta Bubelytė, who presents what I call subjective self nudes, full of subjective emotions. That’s why we decided to exhibit them at the Museum of Romanticism, because she is full of Romantic spirit and she also explores classic Romantic themes like the doppelgänger, the double.

© František Drtikol, Untitled, 1929.

Going back to Latin American photography PhotoEspaña has a very interesting program called Transatlántica, could you explain how it works?

It’s the result of a collaboration with the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and it consists of two aspects: one is the portfolio review held in Latin American countries twice a year, from which we select the best emerging photographers for an exhibition within PhotoEspaña. This year is the case of the show ‘(Re)presentaions. Latin American Contemporary Photography’. Then we also organise an international conference with an open call for papers, for people who are either from or based in Latin America, around PhotoEspaña’s theme. A jury then selects the best submissions. This has been a very important contribution in order to support people who are thinking and writing on photography, as well as to allow young emerging photographers to be reviewed by international experts and to network.

Violeta Bubelytė, Nude 25, 1983. Courtesy Lithuanian Photographers Association. © Violeta Bubelytė

Any highlights from the conference?

I particularly enjoyed the paper by the Venezuelan Lisa Blackmore, and the young photographers performances. The only downside is that, while last year we could afford to publish the papers of the conference – I edited a volume, both in Spanish and English, on the subject, which included the best essays from Transatlántica and translations of classic stuff – this year we didn’t have the budget for a book, but you can download the essays for free.

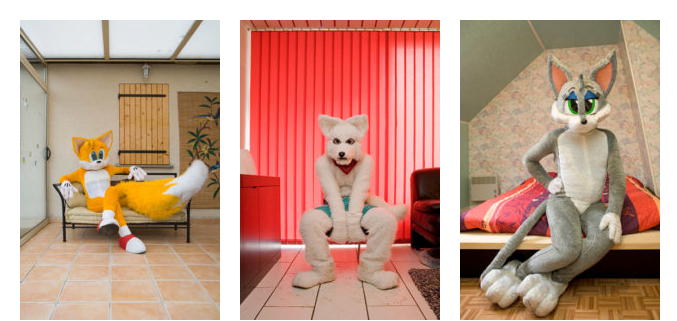

©Roberto Tondopó. ‘Jardín de Flores/ Flower’s Garden’ From the series ‘Casita de Turron’, 2012. Featuring in the exhibition ‘(Re)presentaions. Latin American Contemporary Photography’

I read in the introduction of this year’s guide about the economic difficulties of the festival. Do you think you managed to keep the same quality with less money?

I have to say that I was quite satisfied because despite the dramatic cuts we found other ways, partly through partnerships and private sponsorships, to achieve a high artistic quality. Also, perhaps being a Cuban curator helped, as I am used to difficulties and austerity measures.If you don’t mind I would like to talk about your career as a Cuban curator. How did you develop your passion to contemporary art and when did you decide that you wanted to be a curator?

I think it was more that life decided it for me. Life takes you wherever it wants. At the beginning, I had a vocation for literature, but then I decided to study Art History at Havana University because art was kind of a big enigma for me, a mystery. I started to do research on Cuban artists who were sort of marginalised, either because they were gay or because they were dealing with delicate issues for Cuba at the time. I wanted to support them and I published essays, and then little by little I got more and more involved. I curated my first exhibition on these artists in Cuba back in 1978 and then the Havana Biennial was created. I was a co-founder and member of the curatorial team for three years. Then I left and became a freelance writer and curator.Was Cuban politics something that affected your experience? When I spent three months at the University of Havana I remember meeting amazing thinkers and artists that couldn’t leave the country. Did you have any problems in that sense?

Many problems. I am marginalised from the institutional life in Cuba, although I keep on living there. I had so many difficulties since I resigned from the Havana Biennial in 1989. I was completely sidelined. I cannot publish or curate an exhibition, teach or participate in a panel discussion there. I receive invitations from important international institutions and I have to apply with the invitation letters to obtain a permit to travel. Since these international institutions invite me, the Cuban government always says yes, because to say ‘no’ could compromise its relationship with them. They are very smart.

Edward Weston, Nude, 1936. Collection Centre for Creative Photography, The university of Arizona ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents

In all the three editions that you curated for PhotoEspaña, politics was always lurking behind your artistic direction. Do you think that your personal experience influenced your curatorial practice?

That’s a big ‘yes’. You got it: my work is always linked to politics and social issues. I am interested in art that goes beyond art and tackles social, political and cultural issues. What I find fascinating about art is its possibility of dealing with everything with a unique approach, very different from the social sciences.What comes next for you?

Very soon, on June 28, a show that I curated will open in Amsterdam at De Appel Arts Centre. It’s called ‘Artificial Amsterdam’, which is about how artists react to the city in a subjective way. The subtitle is ‘The city as art’. We are not talking about urban problems or architecture, but about the artist’s personal and individual experience with the city. What’s next for PhotoEspaña? Who is going to be the next General Curator? Who knows…

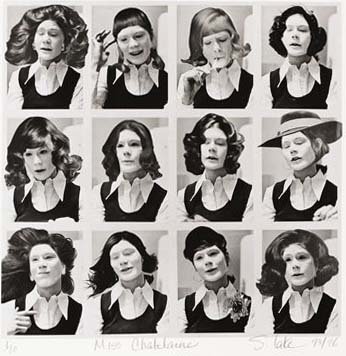

Suzy Lake, Miss Chatelaine, 1973/1998. Gelatin silver print. © Suzy Lake / SAMMLUNG VERBUND, Vienna

Interviewed by Federica Chiocchetti Federica Chiocchetti is a researcher of photography and literary theory at the University of Westminster in London and an independent curator. She is a contributing editor from Europe. Feature Image : Luis Arturo Aguirre, ‘Phoebe’. From the series ‘Desvestidas’, 2011. © Luis Arturo Aguirre