Emaho: Could you share some childhood memories that sparked your interest in design and creativity? Was there a particular moment when you realized this would be your path?

PC: I think, like most people, my journey into a creative life was a unique one. I did not come from a traditionally artistic family. We were the type of family who went to the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum, not places like Tate Britain. So I became interested in creativity and art later on, in my late teens, and in a way that felt quite refreshing. I was interested in science and mathematics, and then the idea of combining those subjects with art and design made sense to me. As I started to study design and later got my place at the Royal College of Art under Ron Arad, things began to loosen up. I felt free and liberated, as though I did not need briefs or reasons to think of ideas. Things just began to flow.

Emaho: Your career journey has taken you from early experiments to global recognition. What were your key inspirations and turning points in developing your unique design language?

PC: I remember early on, in the early 2000s, I had an interview with the Design Museum in London with a similar question to this. I kept using this expression, creative freedom, and I still believe in that. I have always had this instinct to work on projects. I truly believe in projects that I feel deserve to be produced. I was always sceptical about taking on opportunities that felt too restrictive or controlled. In the first decade of my studio I used every minute of every day working genuinely on things that felt meaningful, and I still hold on to that. My output is such an important part of my emotional existence, and the idea of spending time on something I did not believe in would feel very hollow. So I have held onto this spirit of creative freedom, letting ideas take me on a journey into the unknown. Each project feels uplifting and healthy, and without that I would go off kilter. It keeps things in balance.

Emaho: What drew you specifically to furniture design, and how do you connect the ideas of sculpture, utility, and beauty in your pieces?

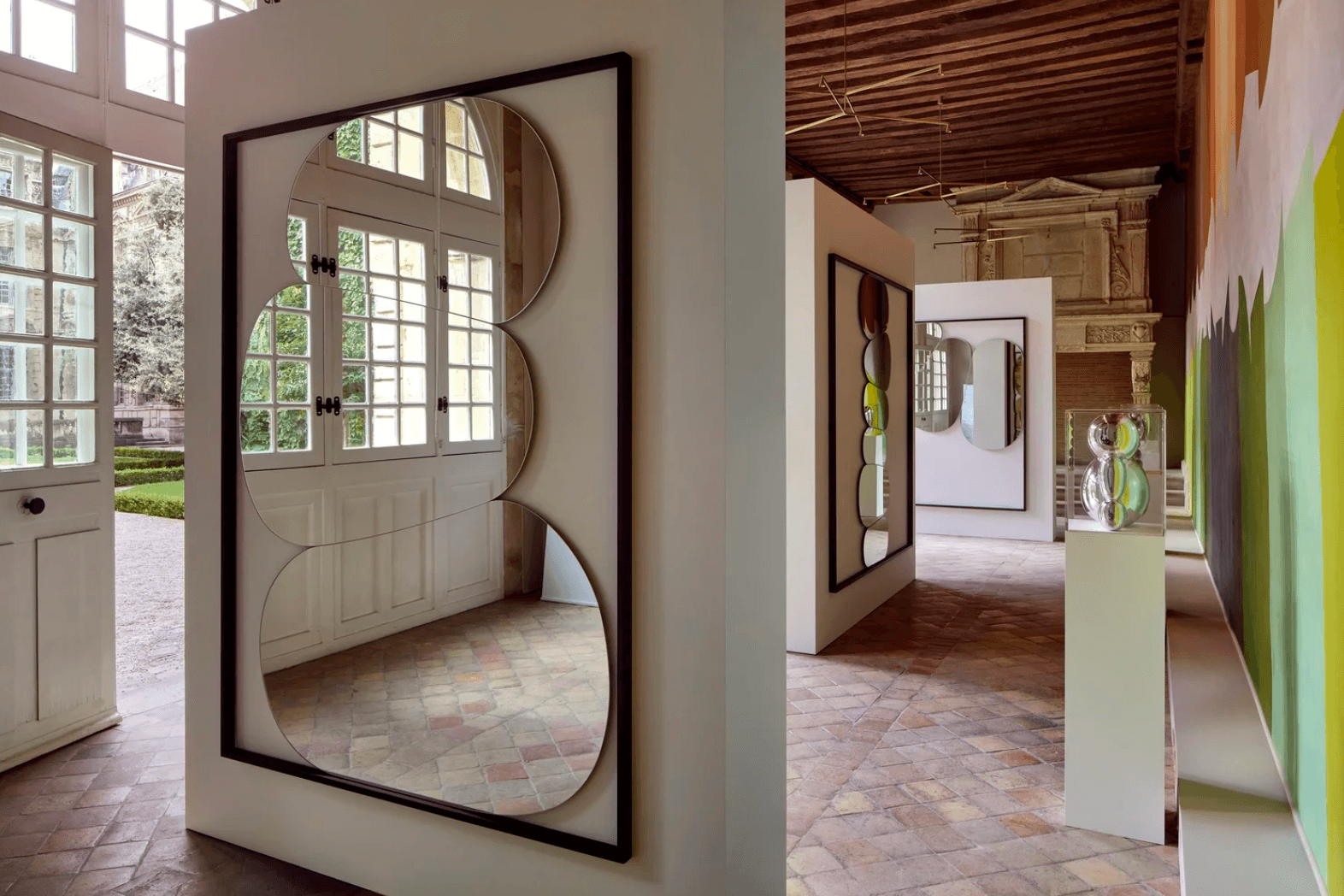

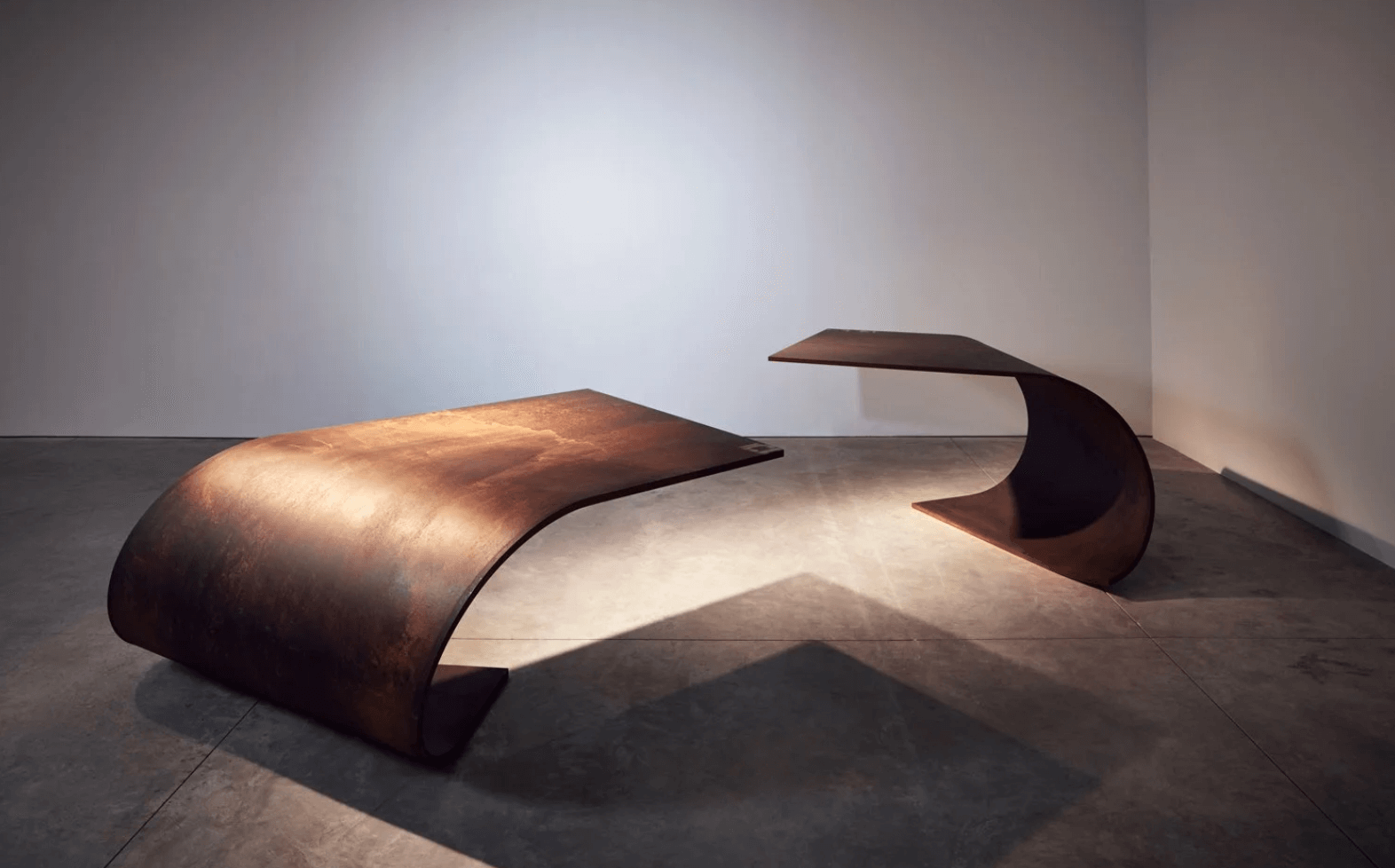

PC: As someone who studied design, I actually came to designing furniture quite late. But there was always this itch to design a piece of furniture. It is a bit of a cliché, but I think many of us feel you have to design a table or a chair at some point. I think the reason it took me so long is that I needed an entry point, a way in. I was not preoccupied with ergonomics or function. I was trying to figure it out from a sculptural place. With Poised, for example, it was about how I could create a horizontal plane of materiality without legs or looking like the archetypal image of a table. The gesture came from me rolling a piece of sketch paper on my table, and then me and my team spent months attempting to bring that effortless gesture to life. That piece became successful, it was exhibited with Friedman Benda in New York, and it unlocked that limited edition, collectible design side of the studio. It allowed experimentation that suited my character. I could create pieces you might describe as tables, chairs or shelves, but without the constraints of industrial design. It is still an important and joyful part of the studio, because it is such a genuine connection between an idea, the studio working on it, physically testing it, and bringing it to life in close proximity.

Emaho: How would you describe the core vision that drives PaulCocksedge Studio? What qualities or values do you strive for with every collection?

PC: The core vision is creative freedom, letting an idea and the energy of an idea take me on a journey. Going into that unknown space can feel vulnerable because I have to embrace any material, any technology, any collaboration. I have become used to that nervousness, but that nervousness tells me I am in a territory where I am pushing myself. What interests me is how I can manifest these ideas and bring them to life in a way that carries the enthusiasm I felt when the idea first arrived. How do you capture that positive energy? I am interested in how an object relates to people, how it can bring joy, spark curiosity and conversation. In that sense the piece almost disappears and becomes a catalyst for human interaction. That is the ingredient that comes from that creative energy.

Emaho: London is famous for its vibrant design scene. How has the city shaped your work and the ambitions of your studio over the years?

PC: London has always been my creative home. It has an edge. It has all these contradictions and push and pulls that make it stimulating and interesting. I feel I am in the moment, connected to the energy of millions of people, and because it is a global city, in a way billions of people. It is multicultural and full of energy. It is not perfect and it does not pretend to be. It is always striving for better ways of doing things, better ways of organising itself, better ways of creating cohesion. With that, plus the history of art, music, design, theatre and politics, it is a cool and edgy place to be. You can walk down a street and it could be the catalyst for a new project. You can see beauty, you can see people struggling, you can see extreme wealth and extreme poverty. It is historic and layered. People talk about London going through a hard time, and in some ways that is true because of political decisions, but that also creates something to react to. When things are spinning, creative people create. I cannot imagine anything more uninspiring than a bland environment, and London is never that.

Emaho: Your modular furniture celebrates adaptability and longevity. What role does craftsmanship play for you, and how do you pursue quality that lasts a lifetime?

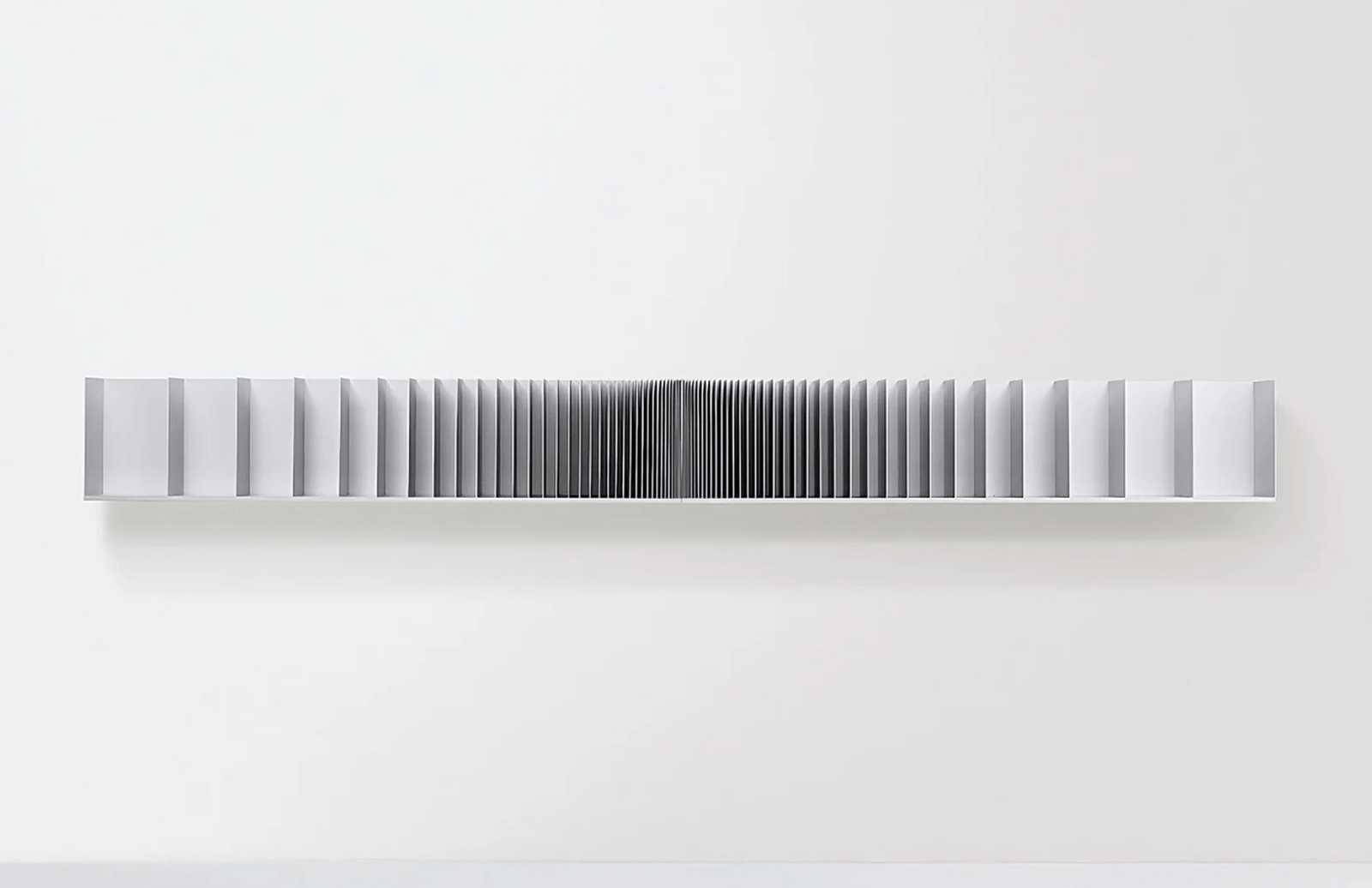

PC: Have I designed modular furniture? Maybe not in the traditional sense. But adaptability and longevity matter to me. Craftsmanship is a difficult word for me to define. I work with materials and processes, and with people who can make things I cannot. The work gets to the quality the idea needs. Often it comes from entering a space where nothing is certain. It is not knowing which is the process. That is where discoveries happen. A good example is the Frieze collection. I buried metal in snow so it would contract, then inserted it into precision drilled holes so that as it warmed up it expanded and locked into place. No glue, no weld, no screw. That could be called a craft. But it is also problem solving and experimentation. And then there is how the viewer feels. Can a piece surprise them, make them curious, make them slow down. That is when the work becomes complete.

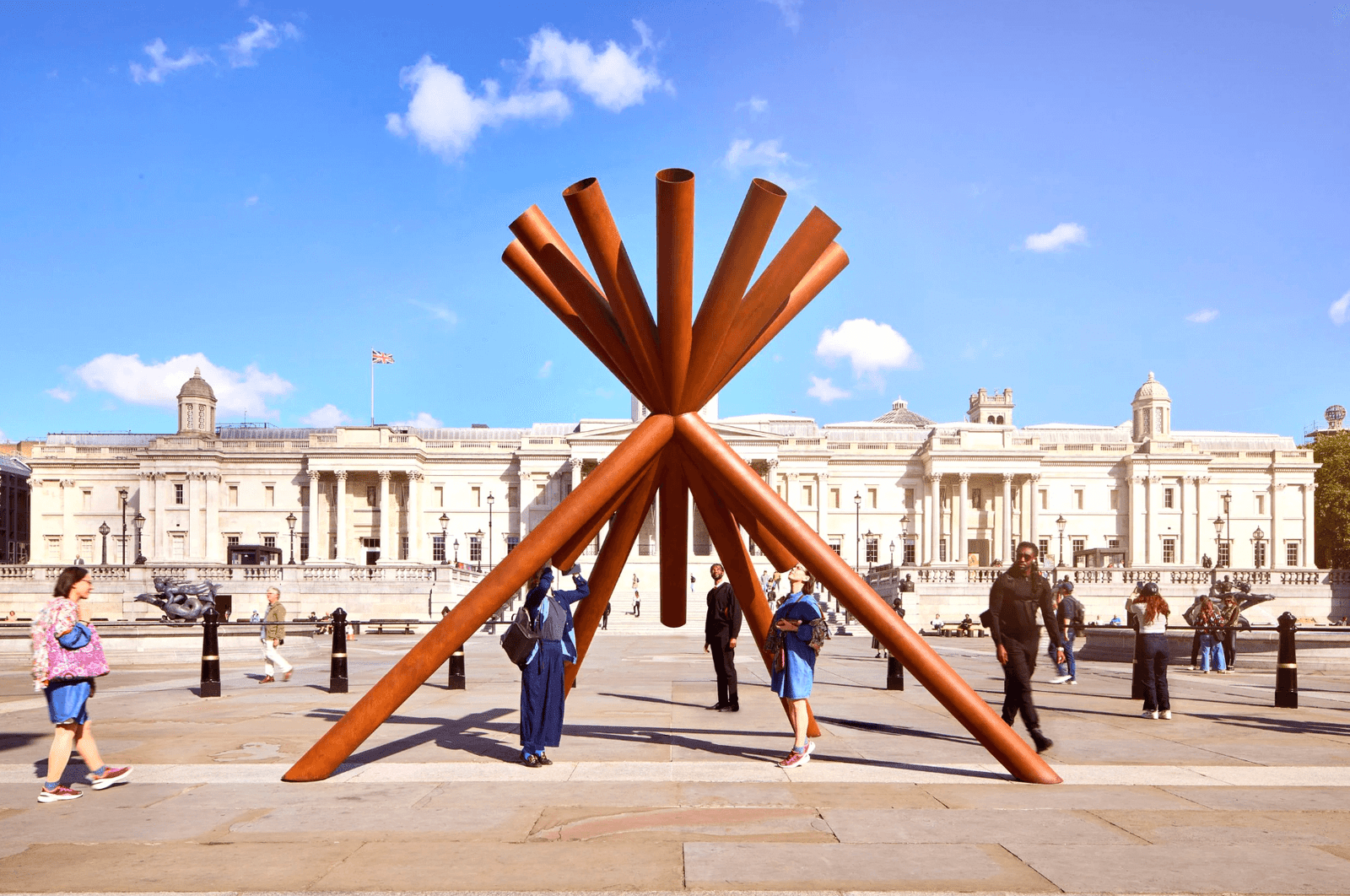

Emaho: Your public art installations – from Nelson’s Column to city squares – encourage public interaction. What excites you about shaping experiences for large audiences?

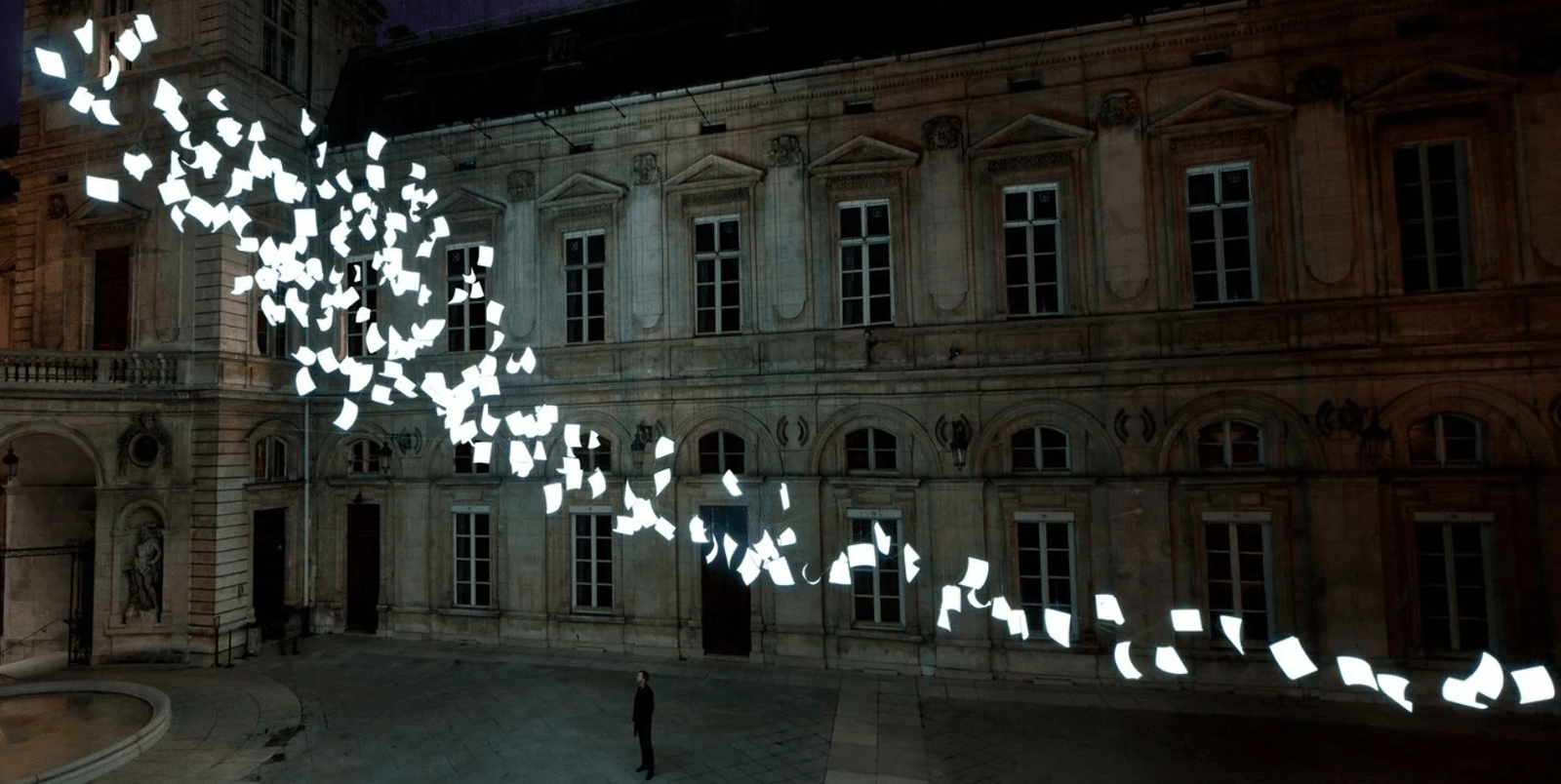

PC: I grew up around street life and community, surrounded by people from different cultures and backgrounds. So working in the public realm feels natural. It means connecting with many different types of people, and that is joyful. With What Nelson Sees, each interaction was completely different. I would have one type of conversation and the next would have a totally different reaction. In galleries, the audience has already filtered itself. In public space it is open. People explore freely and come across the work by chance. There is a freedom in that and I relate to it.

Emaho: “What Nelson Sees” gave people a new perspective on London.What drew you to reimagine icons and spaces, and how did the public respond to this work?

PC: I felt that people in Trafalgar Square would appreciate a new hidden view of London, the view Nelson has seen for almost two hundred years. There is something uplifting about elevating the public in that way. The idea was simple, if you look through here you see what Nelson sees, but that simple gesture created a calmness. People became still. They mimicked Nelson. The work became about time, past and present. Using AI, the view could rewind to show moments in London’s history before the column was built and then move into the future. It was like time travel. When I spoke to people afterwards, they shared stories filled with optimism and pessimism and everything in between. They talked about politics, climate, the cost of living, the weather, all sorts of things. It was thrilling to think that some metal tubes and a bit of technology could create that debate. Those conversations topped me up.

Emaho: How do environmental concerns, sustainability, or recycled materials inform your approach to both furniture and public projects?

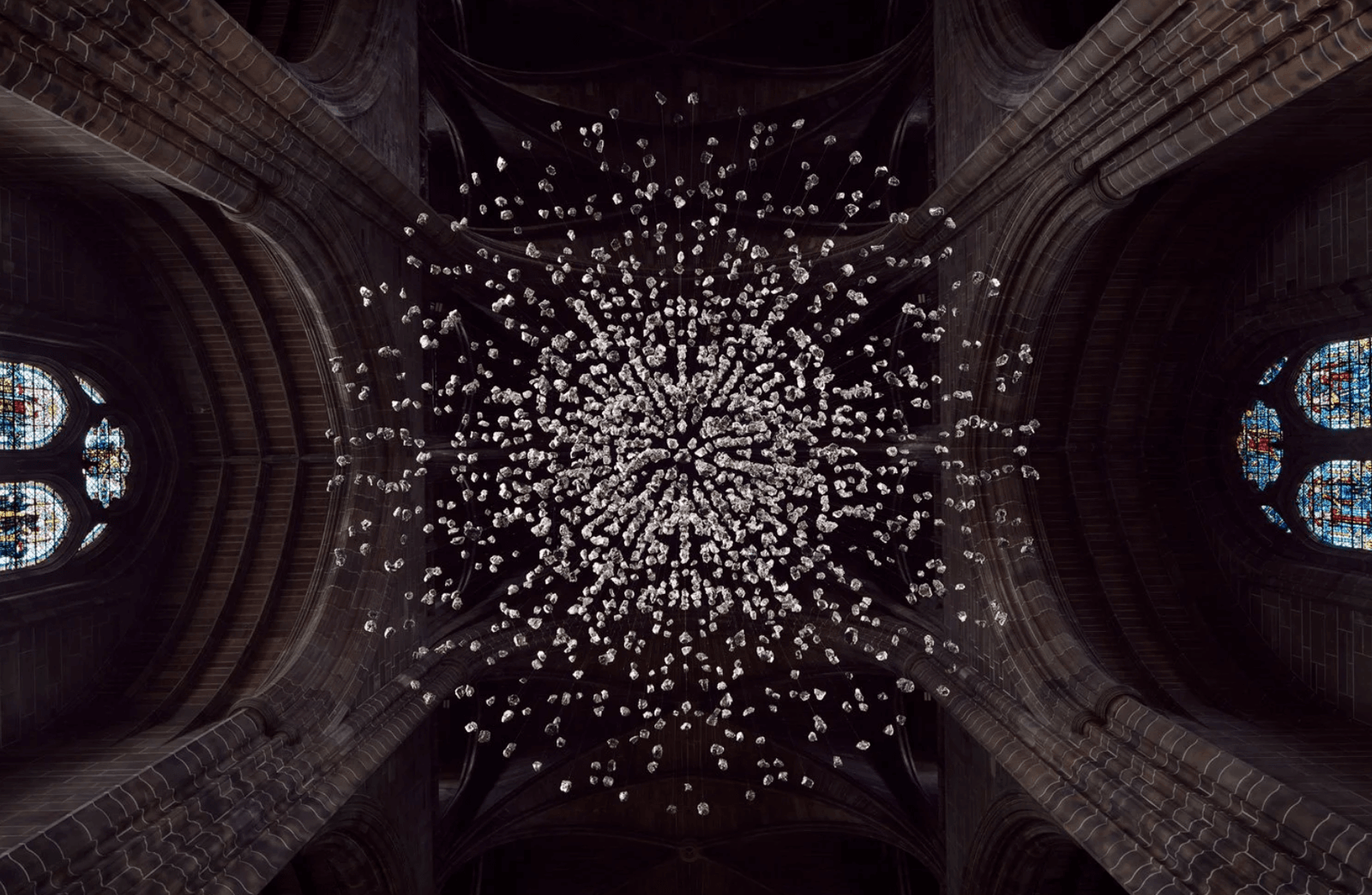

PC: I do not think sustainability or recycled materials are always my starting point, but they appear naturally. Some early works like Styrene or Change the Record used recycled materials because it felt instinctive. I did not have money for precious materials, so reusing felt intuitive and rooted the work in a place and a history. Records carry music history. The polystyrene cup is humble but familiar. With Coalescence I got closer to a material connected to my family and on my dad’s side they were miners, coal. My dad and I went to the last remaining coal mine and extracted hundreds of kilograms of it. The way it reacted to light was emotional. It sparkled like crystalline glass. The piece represented the amount of coal needed to power a light bulb for a year. It was the same year as COP26, and climate conversations were everywhere, my creative energy was in a flow with all of this.

Emaho: Collaboration plays a big role in your work. What have you learned from partnering with craftspeople, engineers, or community groups in London and beyond?

PC: Collaboration is always part of my process. Ideas start intimately with my thoughts and sketches, but conversations with friends and the studio shape them and bring them to life. Ideas take us in any direction, any material or scale, so the people I meet are dynamic and varied. Engineers, craftspeople, specialists. It is exciting to meet these people along the creative journey.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what new ideas, materials, or places excite you most? What do you hope to contribute to the future of design, and how do you want your legacy to be experienced?

PC: Looking ahead I need to keep that creative freedom. People find it curious that every new project from the studio is slightly unexpected. It has been hard to run a studio like that because commissioners tend to like to know what they will get. But because we have been doing it for so long, people now approach us when they want to go on a creative adventure where the result is unknown. They share the view that it is better to work on something that has not been done before and go on that journey where, when we look back, we can smile at each other and know it was a truthful exploration that would never have happened without that collaboration.