Emaho: Najme, could you tell us how your artistic journey began? Was there a particular moment or experience in your life that made you realize painting was your true calling?

NK: Before choosing my university major, I decided to switch my field of study from mathematics to art. This decision was made without any prior mental preparation regarding becoming a professional painter, because at that time, I received no education in this area. Even most of my teachers and my father opposed this decision. But with my mother’s support, I did it, and I still think this decision was very bold.

Emaho: You were born in Kermanshah and now live in Tehran, a city rich in artistic tension and creativity. How has this environment shaped your outlook as an artist?

NK: In this period of time that we are going through the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, the impacts of this experience are evident in all aspects of life, including painting. I have transformed from a quiet and shy small-town girl who was unable to express her desires into a bold woman who tries to do things outside the box.

Emaho: Your work often blends emotion and abstraction, evoking themes of memory, transformation, and human experience. How would you describe the core philosophy behind your paintings?

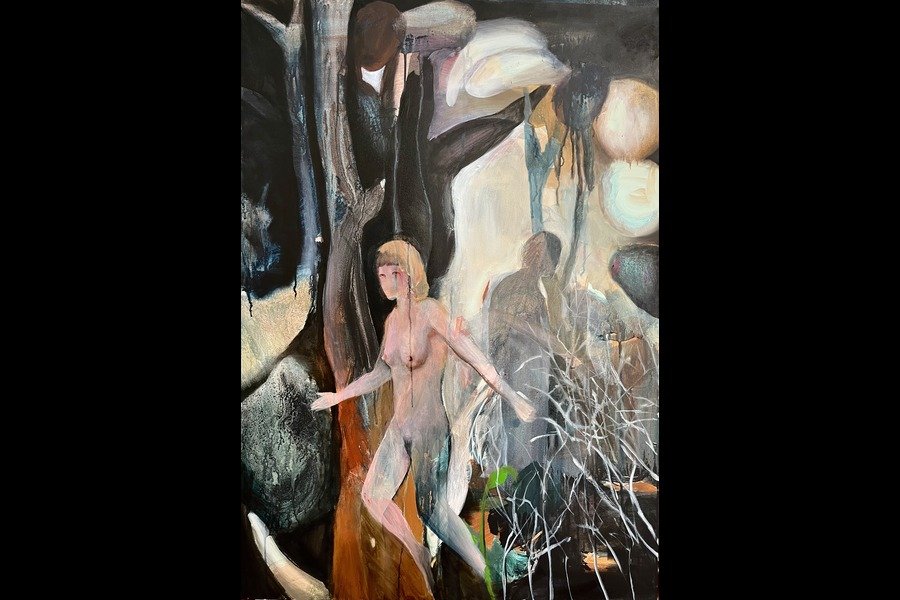

NK: There’s a quiet wonder in uncovering forms and symbols that emerge from pure color. I never begin with a fixed image—only a feeling, shaped by whatever I’m carrying that day: joy, sorrow, or something unnamed. The process is improvised, and my palette shifts with me, reflecting the ebb and flow of emotion. When a piece is complete, I become its first audience. Painting is a way to speak with my inner world—to explore and express the layered dimensions of my own existence. Each work becomes a narrative of that exchange, connecting what’s felt within to something that can live outside of me. This introspective experience is central to my practice. As an experimental artist, I remain open to any material or technique that serves the work. I refuse to confine myself to specific mediums or subject matter. Early in my career, I came to realize how self-censorship—especially in a country where art is subject to repressive control—could quietly limit artistic freedom. That recognition was both painful and clarifying, and it continues to shape my approach: to create without fear, and to remain attuned to the possibilities within each moment of making.

Emaho: Your recent solo exhibitions, including Heart-Devouring Love at Sharif Gallery, reveal a poetic dialogue between form and feeling. What inspired that series, and how did viewers respond to it?

NK: In general, my lived experiences are the main source of my works. The pieces in this collection are also inspired by the experience of a complex and profound relationship that I went through over the past two years. Additionally, along this path, the issue of censorship was a major concern, and I realized that to work freely—both in concept and technique—I needed to wrestle with a lot, and I tried to overcome them. Upon seeing *Letting Go of the Frame*, my audience is initially a bit surprised, but at the same time, they try to view the works as independent pieces detached from their context.

Emaho: You’ve represented Iran on international stages, like the MENART Fair in Paris, which celebrates artists from the Middle East and North Africa. How did it feel to bring your work to such a global platform, and what were the highlights of that experience?

NK: In this era, In my paintings, I have found the courage to be myself and not censor anything that I am. I draw the naked bodies of women and men without fear of judgment. Reaching this point was a difficult process that emerged from the heart of these changes. In this moment, I first removed my headscarf, then in other areas of my life, layer by layer, I discovered where I had been censoring myself. In some places, I wasn’t even aware of this self-censorship! Now, I am still in the process of uncovering these layers one by one and moving forward. It is important to me to have conditions where I can share the results of this process with complete freedom with others. Because in my own country, except through social media or open studios, I cannot do this.

Emaho: Many of your compositions seem to explore the space between vulnerability and strength—echoing the Menart Fair 2025 theme, “the strength of softness.” What does this phrase mean to you personally, and how does it connect to your artistic process?

NK: We, as humans, are a collection of contradictory and diverse emotions and traits. We are simultaneously vulnerable and powerful. These are human characteristics, and of course, they manifest in the work. They are not separate from each other.

Emaho: You’ve exhibited across Iranian and international galleries, from Tehran to Paris. How do different audiences interpret your work? Do your themes resonate differently abroad compared to home?

NK: Honestly, that’s a question you should ask my audience! But I hope both groups can view the works as independent pieces detached from their context as well.

Emaho: Iranian contemporary art is gaining increasing recognition worldwide. How do you view Tehran’s current art scene—its energy, challenges, and opportunities for young artists like yourself?

NK: We are in an era of many and interesting changes, and personally, I want to be a creator and driver of part of these changes. Now is the time to take a step forward and distance ourselves from the conservative space. I see many talented artists in Iran’s art scene, but a bit of courage will lead to profound changes.

Emaho: Can you walk us through your creative process—what does a day in your studio look like, from the first spark of an idea to the final brushstroke?

NK: Yoga, one to two hours of work, cooking, lunch and rest, a few hours of work in the afternoon, and then in the evening recreational activities and spending time with friends.

Emaho: Finally, what message or feeling would you like people to take with them after standing before one of your paintings? What do you hope they remember long after leaving the gallery?

NK: A moment of reflection and curiosity: the idea of compelling my audience to truly *see* is incredibly appealing to me.