India –

Photographs create a frame of the world and the photographers place within it, a personally composed fraction of time – a re-enactment in the theatre of memories. This can be said of Pablo Bartholomew’s incessant search for the self in this exhibition – his own identity illustrated once again through a sense of place. Following a series of displays on his formative years in Mumbai titled Bombay: Chronicles of a Past Life, we take a step onward into Calcutta, the home of his grandmother and a city in flux: caught between a colonial past and the post-independence haze of modernity.

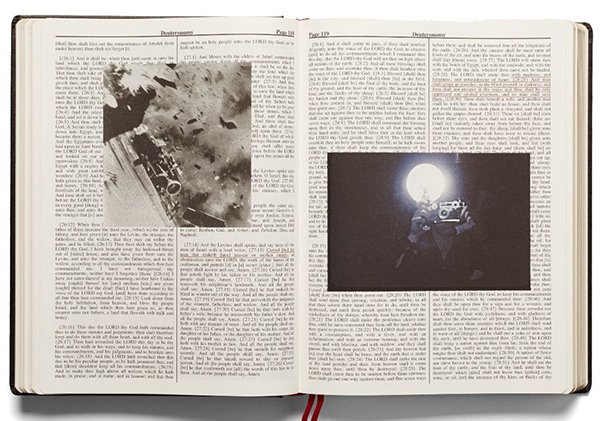

Bartholomew speaks of the camera as a ‘shield’ and a possessor of great power, with the ability to make History into Legend. At the same time he treads two gritty registers of life – an outsider looking in, a position that offers insight and relative objectivity; but also an insider with the authority to calibrate images as personal biographies of city life, visualised through dense black and white images shot on film. Propelled by an inner-compulsion to capture varied sections of society, its marginalised inhabitants with craft and dexterity is like gauging its shifting pulse, a second that may eke out gradually over the years – a veritable lifeline. In achieving this, Bartholomew’s narrative of Calcutta is not simply evidence of a bygone era; not merely an ephemeral encounter between a photographer’s aesthetic and his subject nor an apparent documentary of the streets.

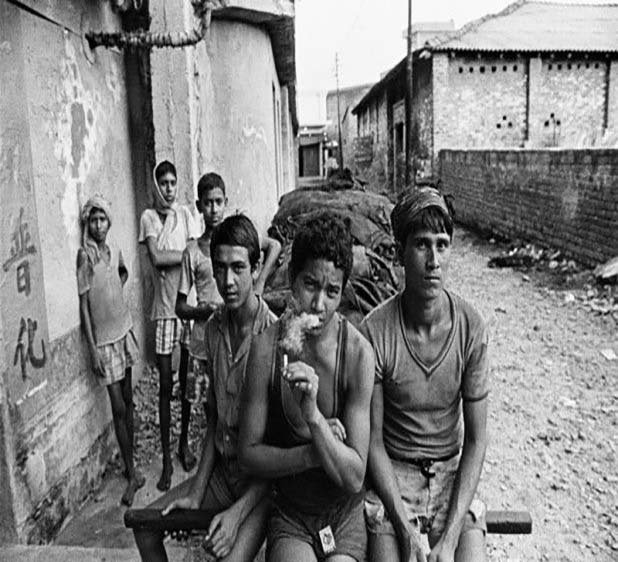

Chinese man and girl with worker Tangra Calcutta-c.1978

Emaho : Over the last several decades, you have deployed the camera as a means of the ‘everyday’ with an underlying social commentary. At the same time it is a personal narrative representative of liminal/existential spaces encountered by you. Photography too has transformed into a leading expressive tool of the ‘citizen’, addressing subjectivities across the board. Do you feel that the contemporary moment is more attuned to such statements, and why did you think of reviving the Calcutta series at this time, a city (incidentally) that was the first to witness the coming of photography in India?

Pablo: I make two distinctions in my work, one I could call ‘slow’ photography that is driven by desire; and the other is ‘fast’ photography that is driven by the need to earn money. The ‘slow’ photography phenomenon is what is now being brought out from the archive in a series of exhibitions. The ‘fast’ photography occurred when I failed to find recognition as well as the capacity to earn a living through ‘slow’ photography. I began my career working as a still photographer, moving my way up through the advertising and corporate industries in India.

Not finding enough fulfilment within these fields, I yearned to be discovered internationally in the editorial world and found a news agency to represent me and began to work internationally within the media there. Once the media beast swallowed me up, it put a stop to my ‘slow’ photography which looked at the ‘outsider’, at marginal urban subcultures, even my friends and family. This happened as I got so preoccupied by news events that took place from the early 1980s to the end of 2000.

Christmas Dance Tangra Calcutta-c.1978

The ‘slow’ photography also dealt with the twilight states of people and urban environments that have always fascinated me. I guess it has something to do with one’s own mental state or feelings of being on the fringe, something to do with my very mixed origins.

Today, images are looked at very differently, because the reading of them has changed radically over the last 15 years. A majority of people are more visually receptive and literate since access to making images has increased because of the digital age and the opening up of economies. A greater availability of books, cameras and improvements in printing technology – all these have contributed to this new literacy.

However, as a result, so much of what has already been done before in photography is being repeated in the name of being ‘new’. Historically, personal space has been something that artists have always played with within the arts – whether in painting, filmmaking, photography or in writing. Whether it was the caveman or the great masters like Rembrandt or pop-artists like Warhol, each have played with the idea of the ‘self’. This same kind of work has been done in other parts of the world decades ago. So what is considered ‘new’ here in India could have existed somewhere else well before.

In some ways, my work done three decades ago can be looked back upon with a different eye or a different reading because they show cities, people and places, as they may have been then – and obviously now, there has been a great transition. In that manner, the earlier photographs provide a visual record on one level, but also punctuate what had already been done by me, which is often being repeated as the ‘new’.

Calcutta represents an important, unexplored family link which I started to discover but quite abruptly abandoned, like many other threads that I started but were swallowed up by ‘fast’ photography. This is why the images in this exhibition can be read as notes in a diary that I hope someday to extend; someday soon.

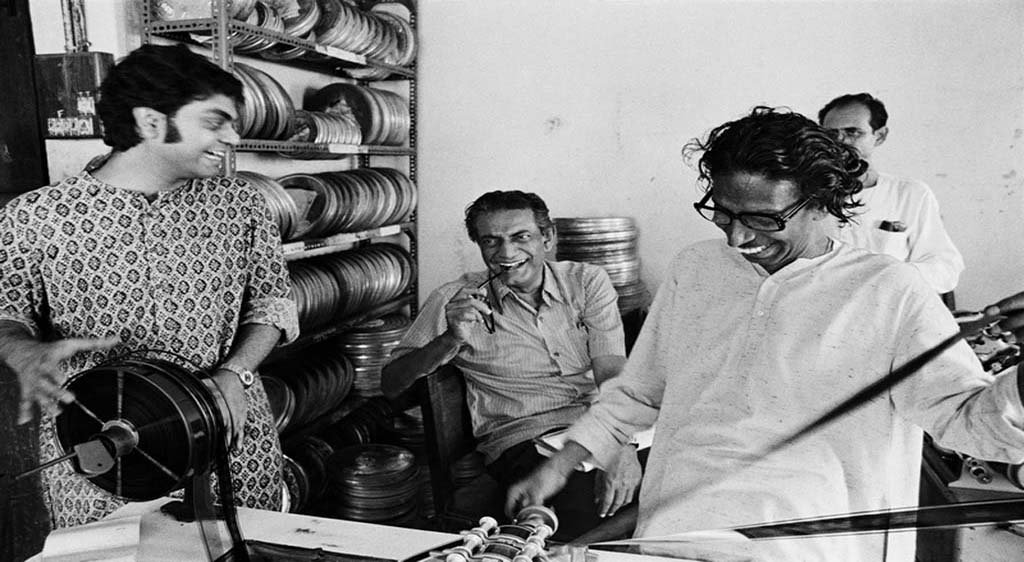

Ray with son in editing room, Bombay c.1978

Emaho : The engagement you have had in the field is both as a photographer and a compiler of histories of photography seen through your family archive. Do you then see a more intentional transaction between past and present and do you think photography allows you to objectively piece together the past?

Pablo: Shutting down from ‘fast’ photography, because of the slow-down of the media in the West, I turned to look at my father’s and my own archive as a way of rediscovering and finding threads of work that I had abandoned. At the same time, it became important to start excavating and showing what we had done. This also served a purpose – to make factual corrections and notes and thereby contribute to the ever-growing and changing history of photography in India.

For the past six years I have been working with my father’s photography archive, putting out a series of exhibitions – at Sepia International (New York) in 2008, at PHOTOINK (New Delhi) in 2009, and Chatterjee & Lal (Mumbai) in 2010. The three galleries funded the publication of his book, A Critic’s Eye in 2008.

In my father’s case, it hasn’t just been the photography. For the past 15 years, I have also grappled with his archive of critical writings on art. It is only this year (2012), that I was finally able to self-publish a vast selection of my father’s writing on the birth of Modern Indian art, titled The Art Critic.

I have photographed what was around me and still do. Journeys were made then and they continue even now. So I have always recorded what was around me and intrigued me.

The engagement was very simple – to look, to see, and to capture; to fill some voids that were created in the past and remain even now. In some ways it has been a form of therapy and sometimes a shield. And in our family, we lived our lives and recorded them, and if now some of it has become ‘history’ then so be it. We all make up our own language as we go along.

The archive is a reservoir of this language, and it needs to undergo a constant process of re-engagement and reassessment, in the same way that language changes and evolves over time. This is what archives are for me. They are the guardians of our memories.

To answer the second part of the question, there is nothing in the creative process that is truly ‘objective’. It is always intensely personal. Having a distance from the original process or experience gives you some advantage. Sometimes one feels strongly about moments that are immediately captured because there are fresh emotional associations involved, and that can sometimes blur one’s judgment. Time is a great filter in terms of creating ‘objectivity’ and letting one gauge whether the freshness still remains. The past can only be ‘pieced together’ if there is this relative distance. Otherwise, it doesn’t constitute ‘the past’. This is the underlying idea behind whatever I have put out from my archive.

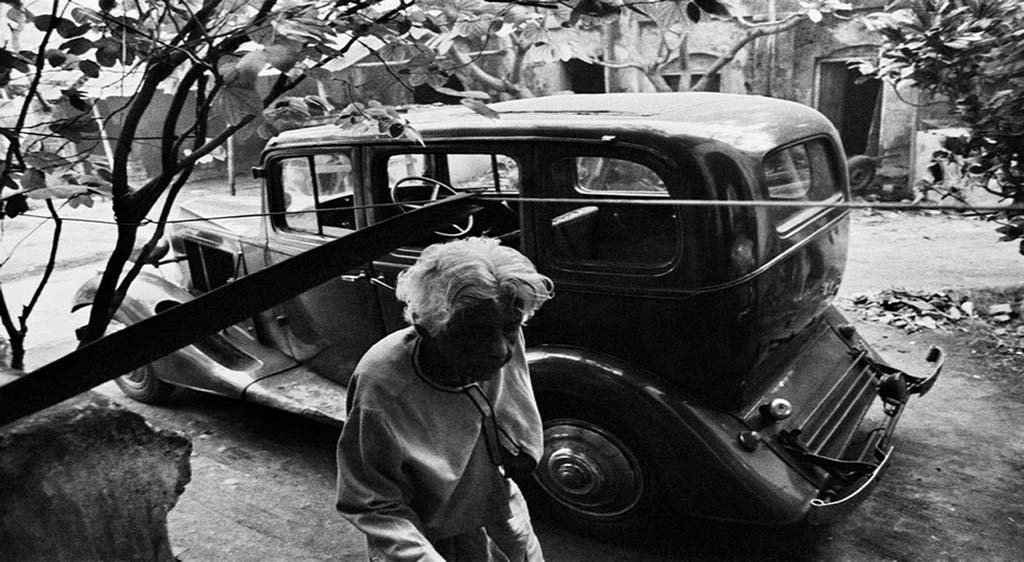

Street acrobat,Calcutta, c.1978

Emaho : There is a generation that you are part of – one that developed out of a Nehruvian/ Gandhian era and found great freedom and expression through the arts. Taking you back in time to your work on drug-abuse which became the subject of your earliest exhibition – how did that moment of the late 1970s affect you as a photographer and chronicler of a time in history? Was the sense of being an ‘outsider’ always edging its way into your work then? Has anything changed?

Pablo: My generation came at a very interesting cross-section of history when Western travellers for the first time, came to India overland – in buses, vans, or hitchhiking. With them came the music and the drugs. So in a sense, for my generation it was a kind of cross-cultural pollination. This drew me into documenting the lives of this subculture as well as my own place in it. Freshly thrown out of high school, and being ostracised and marginalised by Delhi’s social circles, I felt like an ‘outsider’ and was drawn to documenting underprivileged and marginal groups, doing my first exhibition at Art Heritage in 1979, which finally dealt with these themes and issues – of the Eunuch community, the red-light areas, the opium dens and people on the streets.

I have always been drawn to the marginal – and that is what the work on the Chinese Indians of Calcutta that I did in the 1970s is about. Even today, I am looking at the Indian émigrés in different parts of the world as marginal economic refugees. The looking continues, whether they are the Indians from the French islands in France or the Ugandan Indians in Leicester. The ‘outsider’ is not just a sexy concept; it is what one feels and who one is.

Girls in a bylane Tangra Calcutta c.1978

Emaho : In some of your more recent exhibits, you seem to be thinking about the lives of spaces. The work on Mumbai and now the ones you reveal of Calcutta provide an array of iconic and enduring images. Who have been some of the photographers that have influenced your vision of the world, and what are the points of reference that had an affect on you to create these biographies of cities?

Pablo: I’ve been bringing out work in batches. The last show I did a year ago was titled Bombay: Chronicles of a Past Life. This was about the city where I spent a lot of time and where I worked. Now I am showing images from Calcutta, where I went as a child, and later; in my mid-twenties, to work. Neither of these city-based shows was put together as a definitive map of the place. They are my personal encounters with the city and with groups of people and professions. To use a sexy word once again, one could say they represent ‘subcultures’.

In fact, as I write this, I am experimenting at the Angkor Photo Festival in Cambodia, by mixing the first exhibition, OUTSIDE IN and the Bombay show. The street photographs of Bombay are displayed on an outer rectangular structure while the inner side displays the more intimate work from the OUTSIDE IN series. Maybe at some point I will mix in a third set – there may even be a possibility of mixing in many more. I enjoy the process of mixing and changing things around.

As far as the influences are concerned, there are so many – from early English photography to the French photographers – to the Americans and the Japanese. All have had a deep impact and influence in some way or the other.

Trams & Buses,Calcutta, c.1978

Emaho : When one delves into the Calcutta series, there is a deep sense of nostalgia as well as antiquity. It is also then a telling testimony on how life has changed. What are the enduring aspects of Calcutta that you see in these images and is there an effort to hold onto the past?

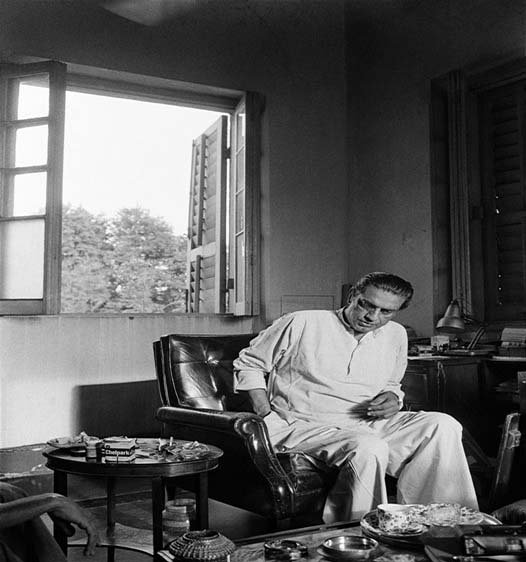

Pablo: Calcutta is still a city that is held by time. I felt it more when I went to visit my grandmother as a child, and it still held that resonance when I went onto the sets of Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players). So when I was photographing it, it wasn’t about nostalgia as it may seem like now. Perhaps with the passage of some more time it may become history? It’s all about transitions and time – story becomes myth, myth becomes legend.

Emaho : How would you respond to the present predicament of emerging photographers in India and what do see happening in the next 10 years, locally as well as globally?

Pablo: I really don’t know. It can be scary especially in the West where the armies of BFAs and MFAs in Art, Design and Photo Schools are being manufactured year after year. This is beginning to happen here in India too. Time will tell. Meanwhile, allow me to be the ostrich with my head buried in the archive!

The Calcutta Diaries and notes on the Chinese Indians

By Pablo Bartholomew

It was during the time when I went to work with the filmmaker Satyajit Ray on the sets of

Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players); first in 1976 and then on subsequent productions; that I got to know some of the actors and crew intimately. Working as a still photographer on the sets, I spent a lot of time in Calcutta at the film studios around Tollygunje. Beyond the studios, the re-engagement with the city of Calcutta, its streets and spaces were of a very different kind from what I remembered in my childhood when I accompanied my mother on her summer holiday visits to see my ageing grandmother.

It was stifling on the studio sets − film shootings had that effect on me. On the other hand it was therapeutic to get away and wander the streets, to feed the inner churning. It was a way of dealing with my own sense of being of mixed origin and of being marginal.

It was this feeling that drove me to explore the Tangra and Dhapa areas of South Calcutta, photographing amongst the Chinese community − or whatever fragments of them that remained. Brutally mistreated, especially after the hate that developed against them as the ‘enemy’ following the national humiliation of India’s defeat to China in 1962, their exodus from the subcontinent had already begun. Many of them were subsequently interned to prison camps in Deoli in Rajasthan.

The Chinese army marched into upper Assam all the way to Tezpur in North Eastern India. So for the political and military blunders that our country made, the Chinese Indian populations suffered, particularly in Calcutta − a community that had lived there for generations, coming at first as migrants from mainland China in search of a better life since the late 18th century.

By Christmas of 1978, around the time I finished taking these photographs, nearly a decade and a half had passed since the Sino-Indian War, and there was always someone’s relative or friend who had migrated or relocated. It was an escape from being constantly prejudiced.

Even after the release from the prison camps, though not openly persecuted, they had to live with slurs of suspicion. And many of those whom I had photographed in the previous year had subsequently left for Australia, Canada and the U.K., leaving India to find a new life of equal opportunities, better economic prosperity and thereby giving them a new lease of life. They managed to break out of those stereotypical professions of past generations – as shoemakers, laundrymen, small-time dentists and low-end restaurant owners.

My engagement with the Haka Chinese community in the Tangra area, this group who lived, owned and ran leather tanneries − and in a diminished way still does − was my first endeavour to document a community in transition, coming to terms with themselves, closed but proud, and friendly. It was also a way to look at my mixed Indian and Burmese origins and find a way to deal with these churnings in my late teens and early twenties.

Photographs by –Pablo Bartholomew

Photography Interviewed by – Rahaab Allana

Rahaab Allana is the curator for The Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, Delhi. The foundation was started by Ebrahim Alkazi thirty years ago and is dedicated to the exploration and study of India’s culture and history. A graduate in history, Rahaab is also a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society in London, and a Governing Committee member of the Alliance Française in New Delhi.