Emaho: What inspired your transition from a career in economics and banking to reviving one of the world’s oldest art forms – Persian carpet design?

Hossein: My family had always been in the carpet industry, which ironically made me want to avoid it. Even my father studied economics before eventually returning to the business—so I suppose escape was never really an option. After university, I worked in finance for about six months, but I quickly realised it was too dry for me. Sitting at a desk from nine to five, staring at numbers, just wasn’t my world.

Growing up, I often travelled with my father when he went sourcing carpets and visiting weavers. That life—travelling, meeting people, experiencing different cultures—was completely opposite to office life. Once you’ve seen that world, it’s very difficult to go back to sitting behind a desk.

Emaho: How does your dual identity—growing up in Germany with Persian heritage—shape your creative vision for luxury carpets?

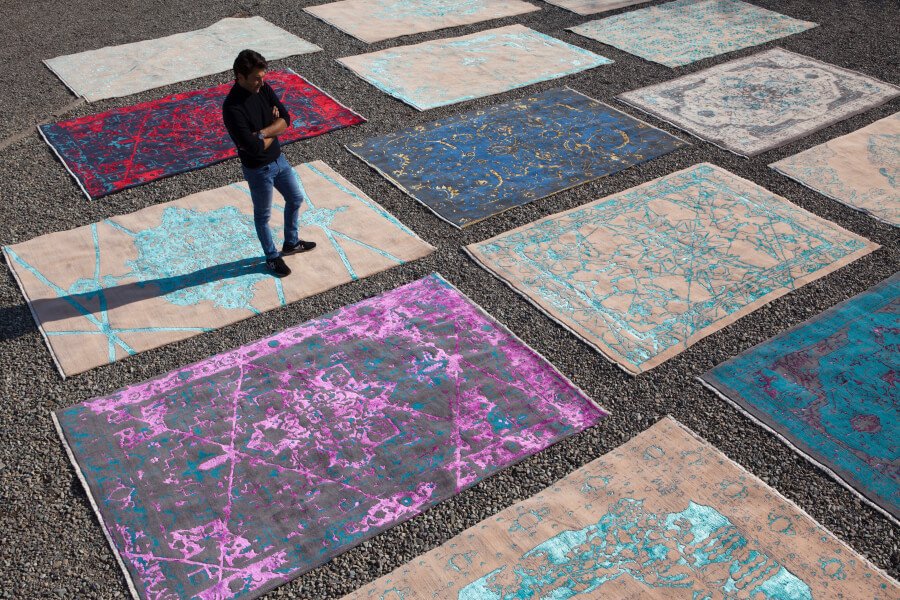

Hossein: I think it’s a perfect combination. In Europe, especially in Germany, everything is calm, understated and restrained—grey, grey, and more grey. That’s how I grew up. In Iran and the Middle East, it’s the complete opposite: loud, energetic, colourful, and expressive.

For carpets, this contrast works beautifully. The discipline and minimalism of Europe combined with the richness and emotion of Persian culture create a very natural balance in my designs.

Emaho: Can you share memories from your family’s multi-generational background in the carpet trade, and how these influenced your passion for craftsmanship?

Hossein: I always tried to accompany my father on his trips to the countries where we produced and sourced carpets—Iran, India, and even the US for antique pieces. It was a world of its own, a microcosm full of visual adventures.

Once you grow up surrounded by that, it becomes part of your DNA. You simply can’t imagine spending your life staring at a screen. You want to explore, to see the world firsthand.

Emaho: Tell us about your bold decision to reinterpret traditional Persian motifs for modern interiors. What resistance did you encounter?

Hossein: When you try to break a tradition that’s centuries old, you face a real storm. It’s like walking to Porsche and telling them you want to redesign the 911. I was in my late twenties, and people in Iran didn’t take me seriously—this young guy from Germany telling master craftsmen how to rethink their heritage.

Finding weavers willing to break patterns was extremely difficult. For over two years, they would simply redesign my designs according to tradition and tell me, “This looks better.” It was exhausting, and I understood why no one had tried it before—it felt almost impossible. But my German side helped; we’re quite persistent when it comes to problem-solving.

Emaho: Your carpets combine Persian opulence with minimalist European elegance. How do you strike that balance?

Hossein: It’s always a rollercoaster. What looks right at the beginning doesn’t always work in the end. Some designs come together in five hours; others take two weeks. If I had a formula, my life as a designer would be much easier.

Emaho: The Tabriz Lilac design won the Red Dot Design Award. What did that recognition mean?

Hossein: It was incredible. The design later also won the German Design Award and received significant international exposure. These kinds of recognition were unheard of in the carpet industry.

Suddenly, carpets became “sexy.” They weren’t just floor coverings anymore; they became design and fashion objects. That shift in perception was deeply satisfying—it showed that our work was changing the narrative.

Emaho: Could you describe your process with master weavers in Isfahan?

Hossein: I work with a team of around 400–500 weavers, all part of a craftsmanship passed down for centuries. Communication has always been the key. Today, after nearly twenty years of working together, we understand each other almost without words.

It’s a continuous learning process—both for them and for me.

Emaho: Why are Iranian highland wool and natural silk so essential to your brand?

Hossein: There’s a reason the first thing people think of when they hear “carpet” is Persian carpet. For centuries, the quality has been unmatched. We stay loyal to the original materials because they work. As they say, never change a winning recipe.

Emaho: How do you see your carpets as emotional heirlooms rather than luxury items?

Hossein: You live on carpets. You grow up on them. They’re part of everyday life. When I think of my childhood, I remember playing at my grandmother’s house, surrounded by red and blue Persian carpets. They gave a sense of warmth and security.

I hope my carpets create the same emotional connection and become part of people’s memories and family histories.

Emaho: What were the biggest challenges when launching your brand in 2009?

Hossein: I believe there’s never a right or wrong time—you just have to start. I launched right after the financial crisis at INDEX Dubai. I brought 25 pieces, convinced they’d sell instantly. We sold one.

It was disappointing, but I believed in the product. We made a strong impact because no one had seen contemporary Persian carpets from Isfahan before. The combination of quality, innovation, and a strong story caught the attention of the press, especially in the MENA region. That visibility helped us immensely.

Emaho: How do you keep your work relevant to both traditional collectors and younger audiences?

Hossein: Trends come and go, but classics remain. The key is to create something timeless—traditional yet contemporary. You should always feel the heritage in the design. That connection to history is what resonates across generations.

Emaho: What legacy do you hope to leave, and what advice would you give heritage-based entrepreneurs?

Hossein: Legacy isn’t something you define yourself—it’s something others decide. But I’ve often been told that I helped save the Persian carpet, and that makes me proud.

By the early 2000s, Persian carpets had lost relevance in design. Younger generations didn’t want them anymore. With my work, I helped bring them back into contemporary homes and gave them a new image. If I contributed to that revival, then I’m grateful.

For others working with heritage crafts: respect tradition, but don’t be afraid to challenge it.