Peru –

Reading on this book the origin of the word Peru, I remembered the legend I was told many years ago in Sidney: when Capitan Cook arrived at the Australia’s’ East Coast during his trip to map the Oceania continent, he asked- speaking English flawlessly – to a native man about the curious name of an animal that was jumping everywhere, the answer was «Kan Ghu Ru». Cook transcribed the name of the marsupial as Kangaroo, he did not know the actual meaning of the phrase in native language was: «I do not understand you».

In other places worldwide, there are similar legends and all of them have in common that the chronicle witnessing such lexical baptism is unknown. It seems evident that the arrogance of travelers arriving at unknown lands is intended to be highlighted in several versions. To name the world in the last centuries was a function reserved to the representatives of empires, but these non-author stories mocking at the origin of some terms included in our anthropological and zoological encyclopedias are the revenge against their semantic hegemony.

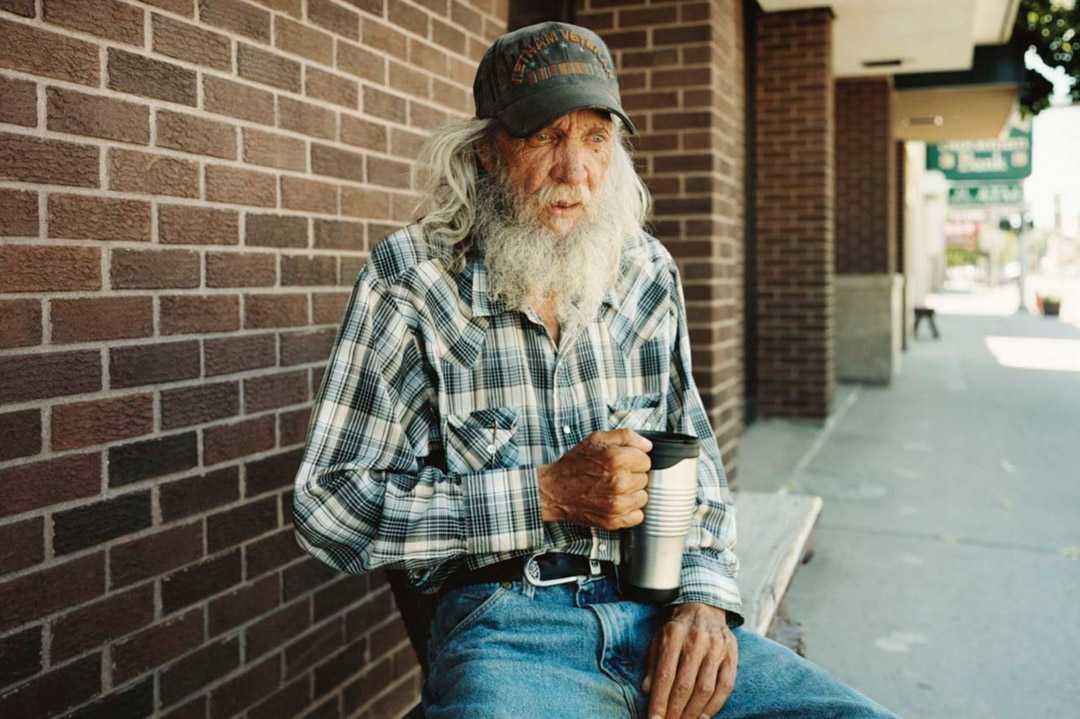

In XIX anthropological photography, to name is to represent, to reintroduce different cultures to Europeans as the others. It is such the influence of this colonial and ethnocentric paradigm in our visual imaginary that it is usual to see photographers from Asia, Africa or Latin America to register their people as they were XIX anthropologist wannabe. That is why the scientific inaccuracy of this work on Peru is its first positive surprise. To decide not to visually map their country is another feature of this photo-essay: a story in first person that is neither in nor out. To decide not to reenact with a “national” complicity, to show reasons of belonging and therefore, to embrace a more ethical view on this broad and alien geography that is the non-urban Peru; a weak stand compared to the historical power of the document; not even the names of the authors guarantee a true Peruvianness.

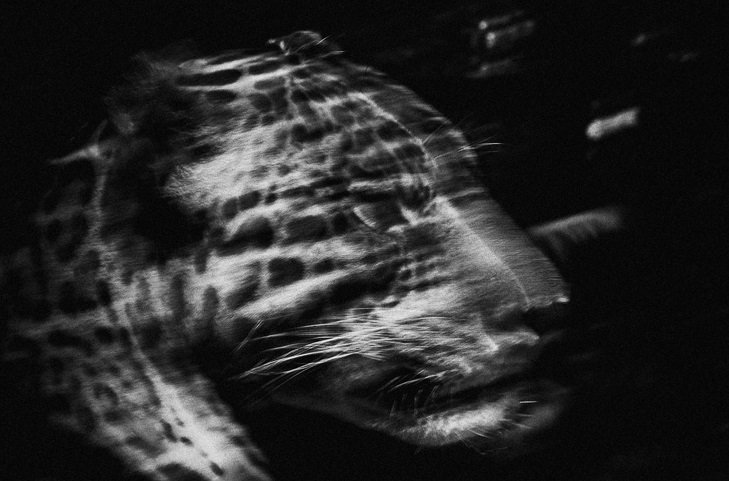

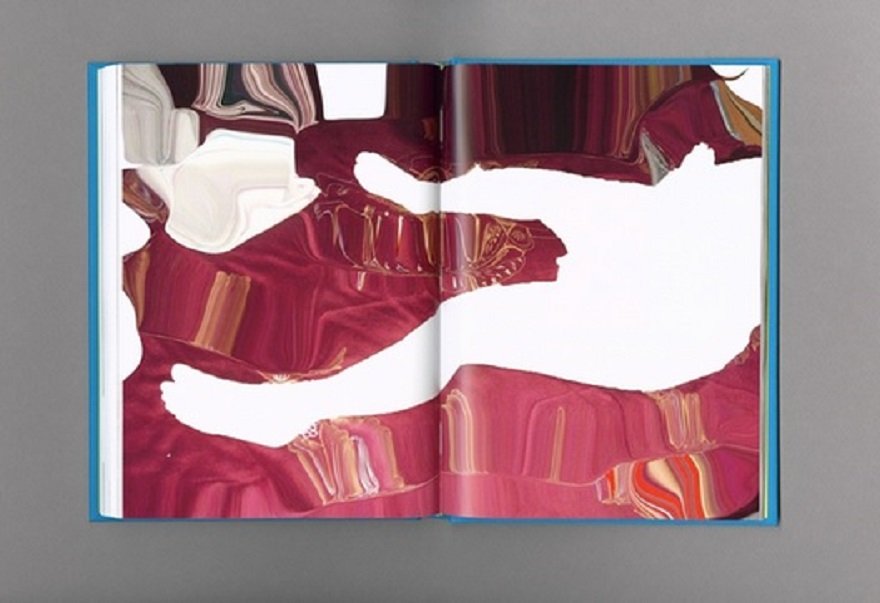

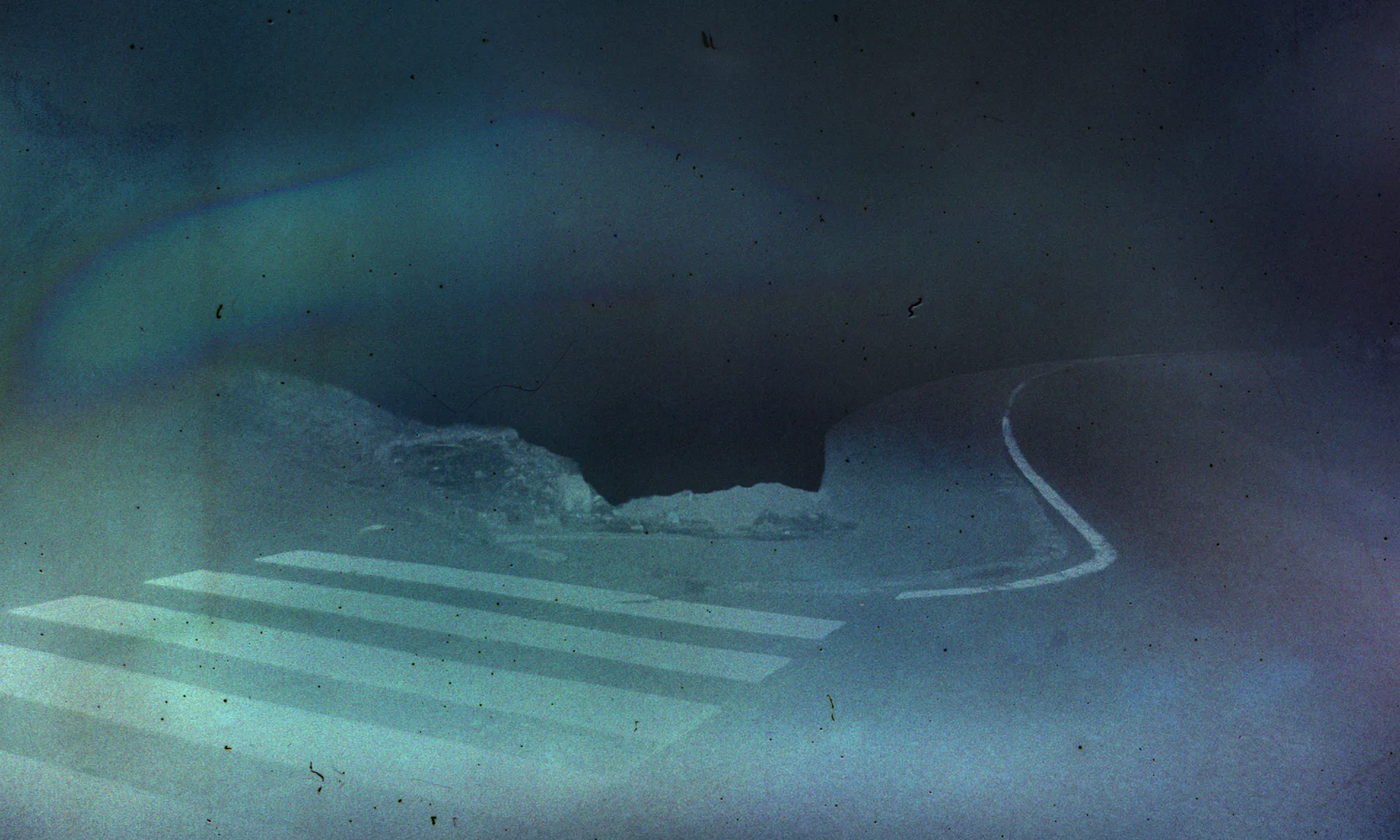

Their trip, their estrangement, contain echoes from a dazzled story from other couple–Claudia Andujar and George Love- done in the 70s on the Yanomami; an emotional trip, kind of initial trip through the land where this Amazonian community dwells. It is the story when contemporary encounter meets ancient times. It is history, in lower case letters, of two photographers’ empathy with a native people; people meeting people. Andujar and Love used color in their pictures; Searles and Nolte use exclusively black and white. Both options do not match their own time. This is weird. For the first ones, it was used to attempt to translate the never ending colors of the jungle, to highlight the hypnotic magic from beyond, to be a witness of the visual and emotional alienation embodied in the encounter. For Nolte and Searles, black and white is a formal means to mix up the times coexisting in the country. Their Peru is in the middle of darkness, this may be the only way to suggest the extension that they do not know. The narration of their encounter with their Peruvian peers is undoubtedly the proof of their own otherness, the impossibility to fill in the dark blanks of history.

Their pictures rise up from the shadows, are scenes lightened by symbolic glow-worms flying around and stopping by according to random motivations and directives. Likewise their story: fragmentary and random, fascinated and passionate: brief. I would say it is closer to a childish tantrum since it is mysterious than an adult reasoning reflection. As the book Amazonia from Love and Andujar, Piruw is an emotional journey album. There are no maps; the map only exists in the political speech. There is no History, there are histories. What cannot be named here, it is just simply shown. It is like, as stated by my admired José Luis Gallero, to confer sense to the magma of the real from its pieces: That is the aim of photography and History. No wonder the father of this last one, Herodotus, having not yet found a word to name his discipline, used the verb historian, which originally means «an eye witness».

Alejandro Castellote