Emaho: Can you tell us about your early life and the moment when photography became more than a way to document family and everyday life, and started to feel like a language of its own?

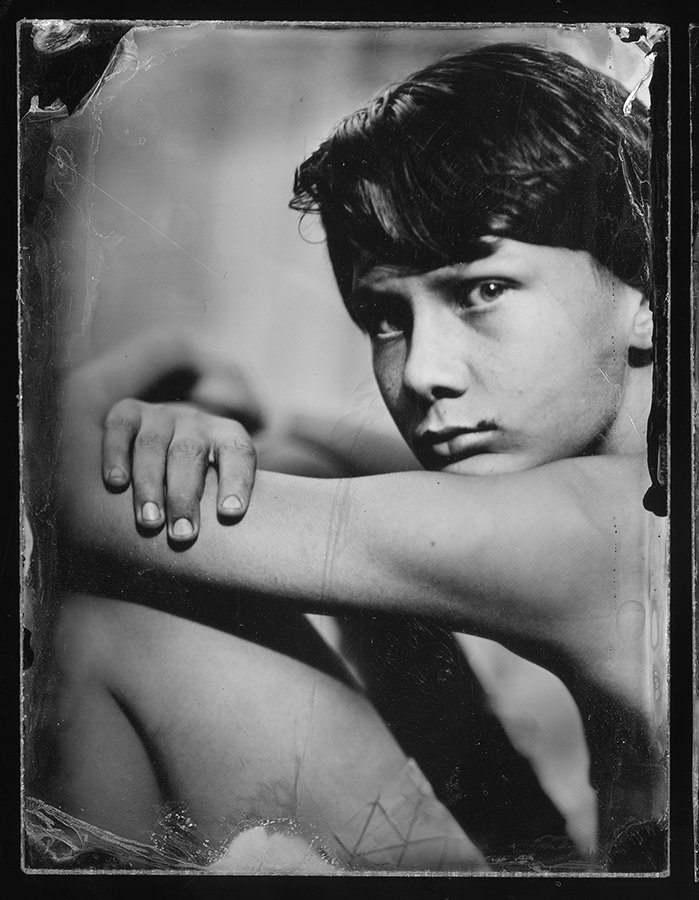

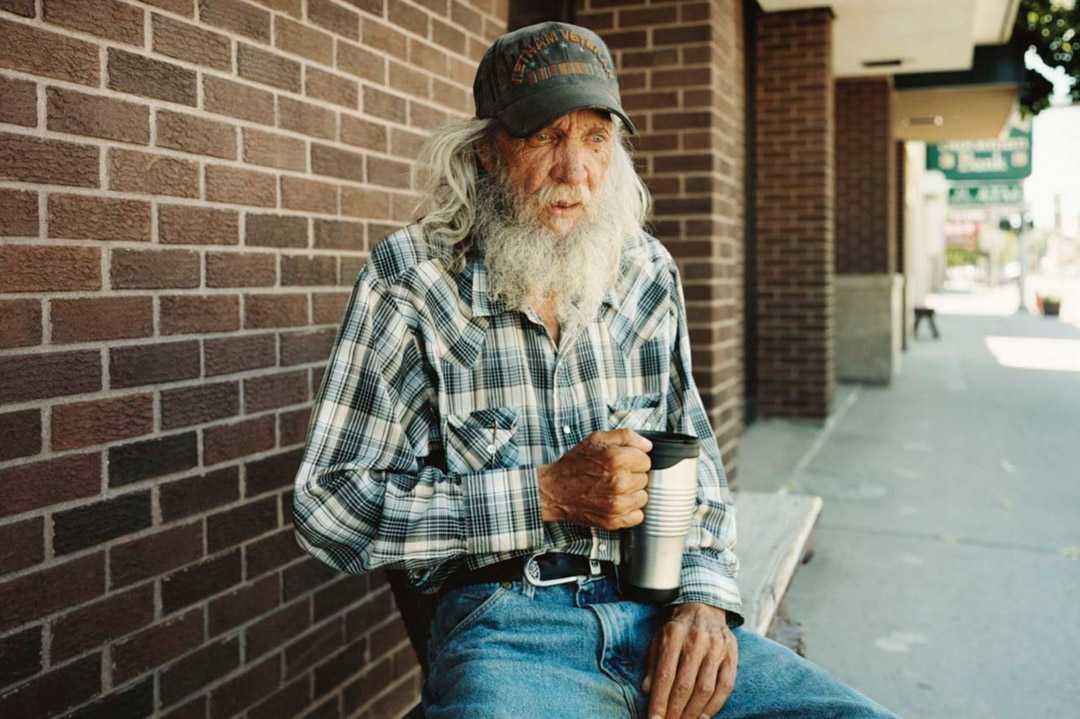

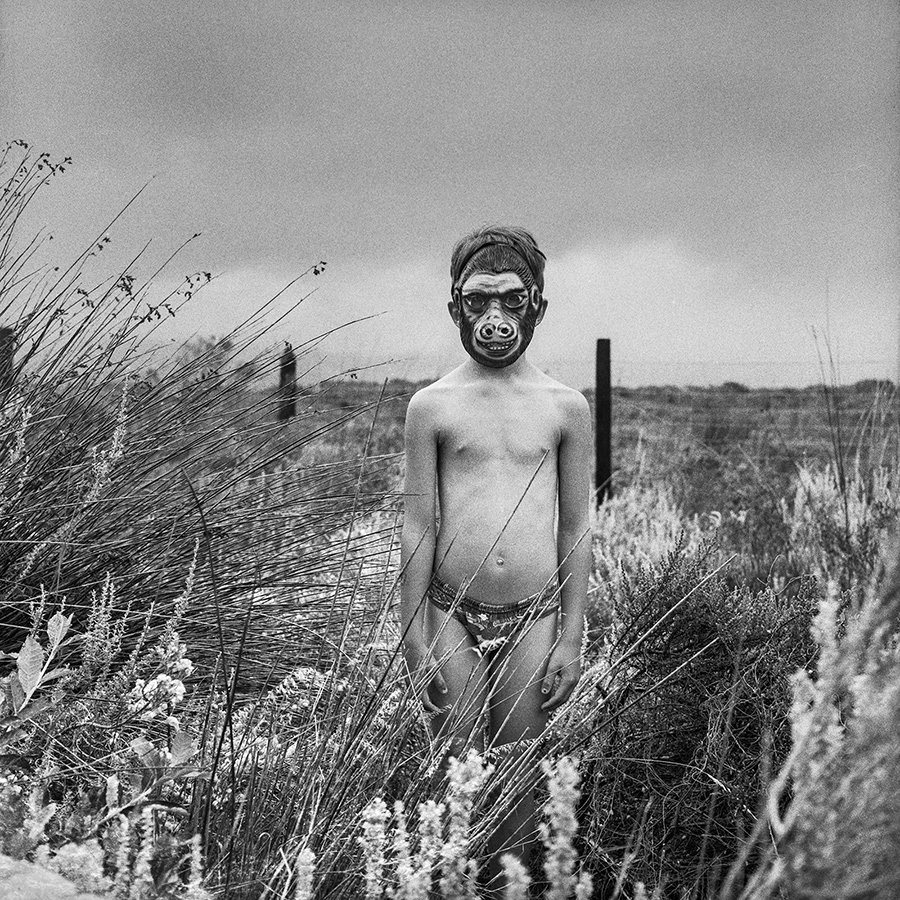

Michelle: Photography was always in my life, just there on the periphery. My father was one of those, 80’s dads with all the lenses and weird filters who constantly photographed my brother and myself. Honestly, I never thought of photography as a career choice, but I always photographed. The shift came, I suppose when I felt I needed to retain something of the experience of having children. The realisation that the moment I was in, was one of the most obviously fleeting human experiences. There is an essence in childhood that is so transient, that if you look away for a fraction of a second it’s gone. I wanted that. The unique brilliance of our own existence, for that nanosecond. Photography became something that I could use to explain my experience of the complicated dynamic of motherhood. Using a very old camera and film somehow also allowed me to have an imagined control over time.

Emaho: You spent over one decades working as a commercial photographer before shifting your focus toward education and fine art. What prompted that transition, and what were you seeking that client work could no longer offer?

Michella: With client work you are always bound by a brief, and I have never been good at following instructions, so having reached a point of saturation my next step was quite organic. Years previously, I had studied photography together with John Fleetwood who had subsequently become the Head of the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. He invited me to come join him and teach at the school which was founded by David Goldblatt. This really radicalized my understanding of photography and the depth to which one can express oneself though the medium. There were all these incredibly talented artists that were communicating through photography, my mind shifted.

Emaho: Over the years, you have mentored photographers from across Africa. When you first encounter a young photographer, what signals tell you that their voice is worth nurturing?

Michelle: It’s never the so-called “perfect image,” it’s often the gut feeling that an image gives me. An innovative approach to using photography as a language, sometimes it can be as simple as their use of light. If there is a particularity in the way a young artist looks at and engages with the world, that is of interest to me. Photography is also all consuming, so I often look for the kind of singular delight in the sheer making of a photograph that always draws me to someone. I get really excited with the idea of developing these narratives.

Emaho: From your experience, what are the most significant challenges emerging African photographers face today – whether access to resources, visibility, or developing a confident personal narrative?

Michelle: Of course access to resources is a major challenge. One cannot just buy a medium format analogue camera, because the real complications of having access to film and a place to process and scan is not always available, complicated or extremely expensive. Photobooks are also a complete scarcity!

One of the big challenges is the struggle with critical photographic engagement, education and audience development. There are pockets across the continent where photography is seen as something important to nurture, but these are few. So often outstanding work is missed, or a lot of artists are forced to work outside of their countries to gain recognition and be able to survive. Photography is often only seen in a commercial sense, so you can become a wedding or events photographer, but expressing yourself using photography as a tool is complicated. Even our bigger art fairs often present photography as a kind of after thought, or resort to the same reliable artists that guarantee sales. That said change is happening, with new art fairs and magazines highlighting fine art photography.

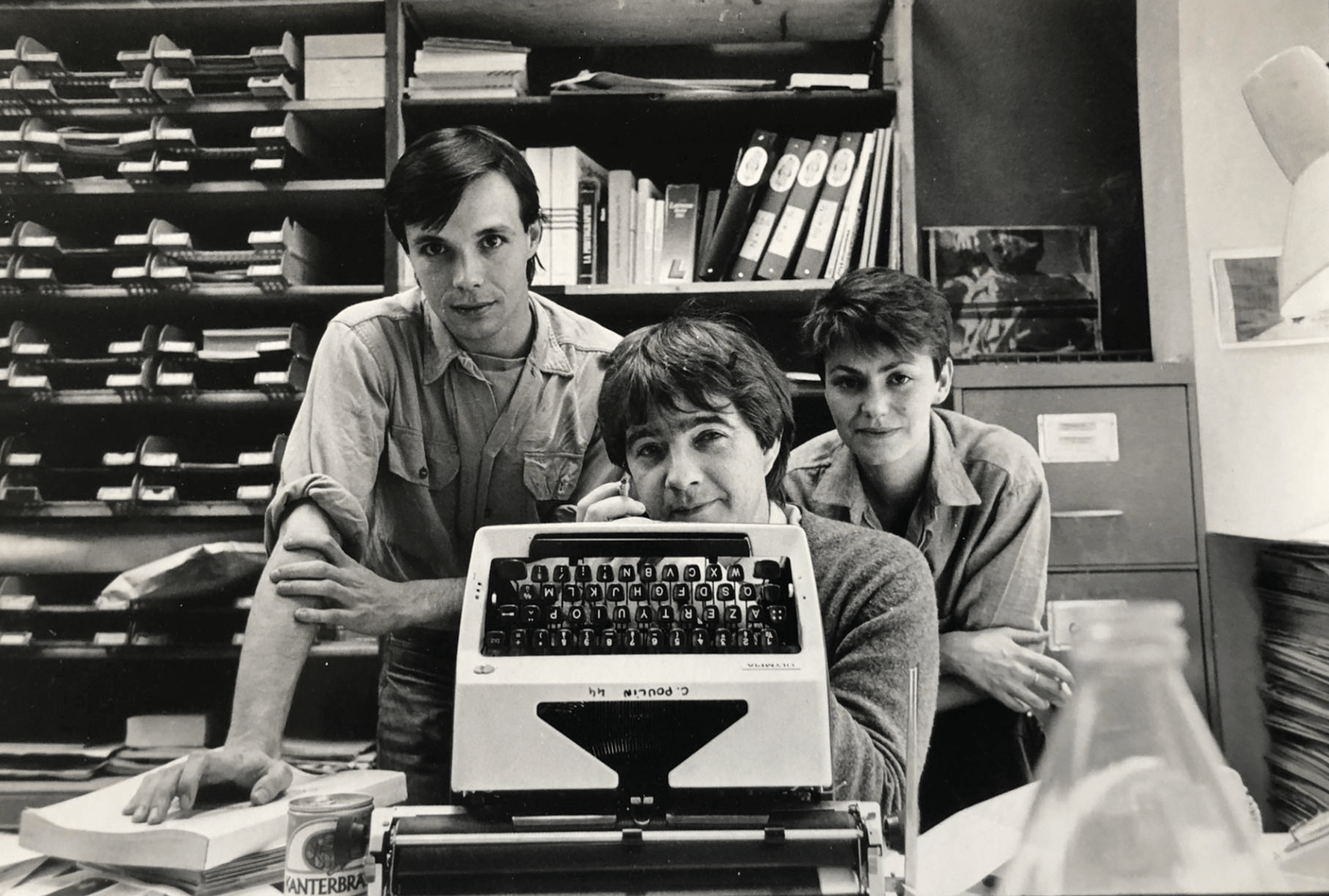

Emaho: Through The Lens Collective began as a small, women-led photographic school in Johannesburg. How did the idea come together, and what gaps in photographic education were you trying to address at the time?

Michelle: Speaking to like minded friends over lunch we toyed with the idea of creating a new platform in South African photography, we wanted to work with people without the myriad of red tape that can be attached to institutions. We wanted an all inclusive space.

TTLC is not an academic platform, it is an experimental space where photographers are encouraged and guided to develop their own practices. The big emphasis has always been on the individual as an artist, and what they have to say and how they are going to say it. So it came from a desire to do better, work with people on an individual basis, in still questioning and never be a kind of photographic factory that pumps out the same results.

TTLC feels very strongly about addressing the underrepresentation of female photographic voices especially in an African context, which culminated in open calls like our annual Women’s Month Platform that we host on social media. Also looking at countries where we can help develop a culture around female photography.

Emaho: How has TTLC evolved over the years, and what do you now see as its central mission within the African photography ecosystem?

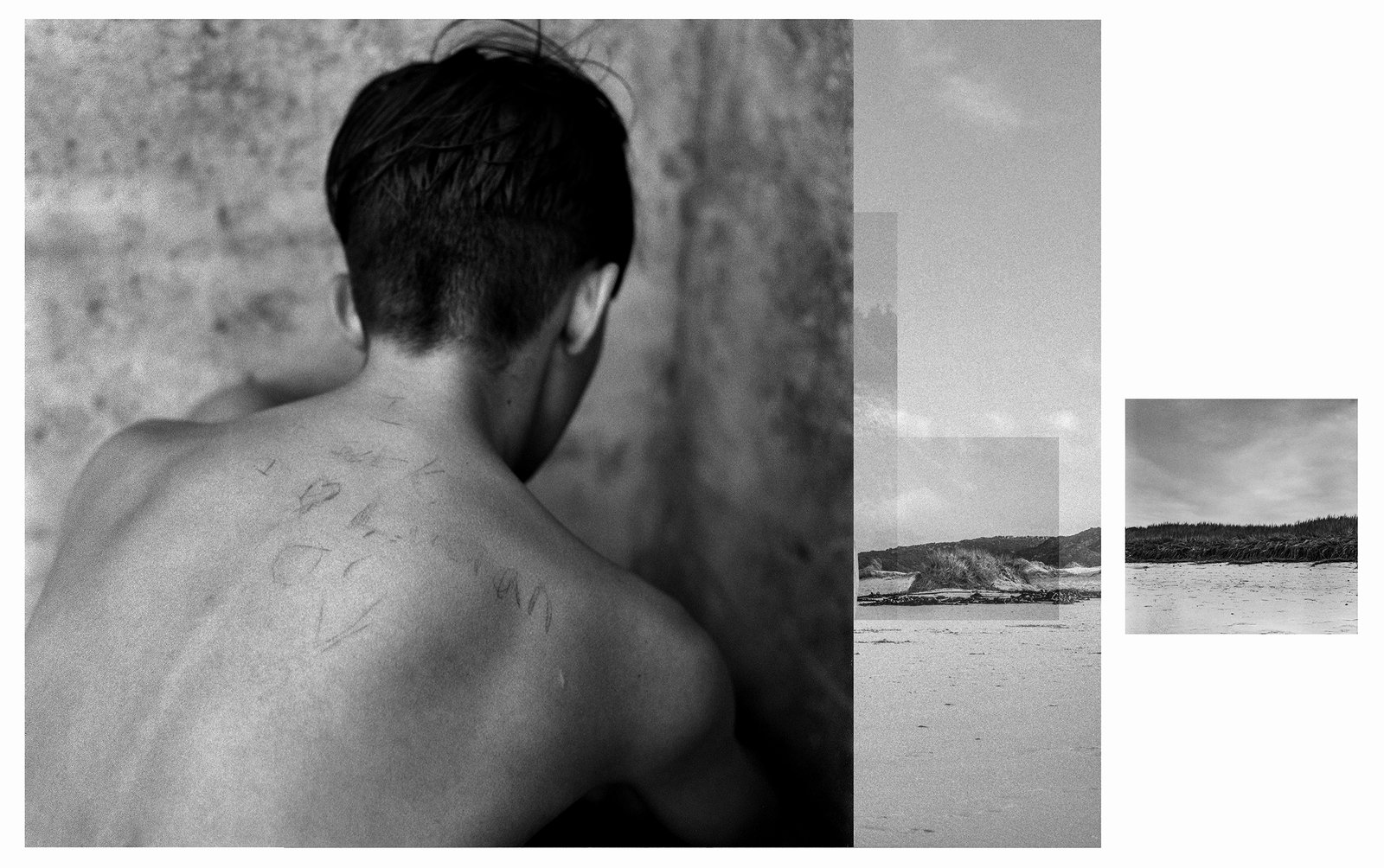

Michelle: TTLC has definitely become more niche, where a very particular type of photographic development takes place. It’s like we don’t even teach photography anymore, but use photography as the way to open our minds and see what we can do with the tools we have. Some artists come with a ton of work that they have no idea what to do with , some only have vague ideas. I navigate that disarray and help the artist find the threads that hold the work together, and develop a strong narrative and understanding for what it is that they want to say. This takes time, beyond what a normal lesson could ever offer.

TTLC evolves, shifts and changes all the time. This process is guided by the members of the collective and their needs. Photographic education, and with that critical thinking has always guided my decisions around TTLC’s output. African photography is as expansive as the continent itself, there are a multitude of important stories to tell, that have previously been ignored, told by others or suppressed.

TTLC creates partnerships and collaborations with like minded artists across the continent and together create mentorships in spaces that can benefit from collaborations. At the moment, we have programmes running with Sudanese photographers and Ethiopian women photographers.

Emaho: Over the past decade, how has your own understanding of photography shifted – in terms of technology, authorship, and the kinds of stories you believe are most urgent to tell?

Michelle: I often think of photography as the punk in the art world, as it can honestly go in many directions at once and feel quite chaotic and unmanageable, but in its essence it is always pushing forward. It looks back and forward at the same time, artists are using old photographic techniques and revolutionising them, but simultaneously also have the most access to incredible technologies. The development of spaces like Instagram, has introduced us to almost everything photography related, but it comes at a heavy cost of mediocrity at times. It can be very difficult for new artists to sift through the information overload and find their own voice without being too influenced by what is trending. I believe good work can sometimes suffer and get lost, and mediocrity is often seen as exceptional.

Work created now is often closely related to personal experiences, artists are considering their complicated histories and considering their personal family archives and what that means in today’s context.

Emaho: You recently co-founded Tombe, an Africa-based photography magazine. What was missing from existing platforms, and what kind of photographic work and critical writing do you want Tombe to champion?

Michelle: Tombe comes from a space of deep interest in African photography, it wasn’t really about what was missing but rather what could be added. We wanted a space where African photography is celebrated and honoured, while asking questions and being critical of the role that photography plays and has played in our histories and the future. We wanted to speak to the artists that are saying serious things about the continent now, where it is going and its history. We also wanted to create a platform for unknown artists where they can see their work, amongst other Africans.

Emaho: As someone deeply embedded in the continent’s photographic community, which 5 African photographers do you believe the world should be paying close attention to in 2026, and why?

Michelle: Africa consists of 54 separate countries which always makes questions like this difficult! The talent is astounding and immense! Maheder Haileselassie (Ethiopia), Jansen van Staden (South Africa), Hashim Nasr (Sudan), Abdo Shannan (Algeria) and of course Lindokuhle Sobekwa (South Africa), are amongst the artists whom I closely watch. They all have very distinct ways of working and story telling that is unique to them. Their constant curiosity about the past and present, unpacks so many new ways of understanding where we live.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what are your hopes for the next generation of African photographers, and how do you envision TTLC and Tombe shaping that future?

Michelle: My hope is that we can prosper and create incredible sustainable platforms from which to present our work. TTLC and Tombe will hopefully be a driving force in helping the next generation of artists to understand the value of their individual insights and their strengths as artists.