Emaho: Could you share a few memories from your early life in Egypt that sparked your curiosity about photography?

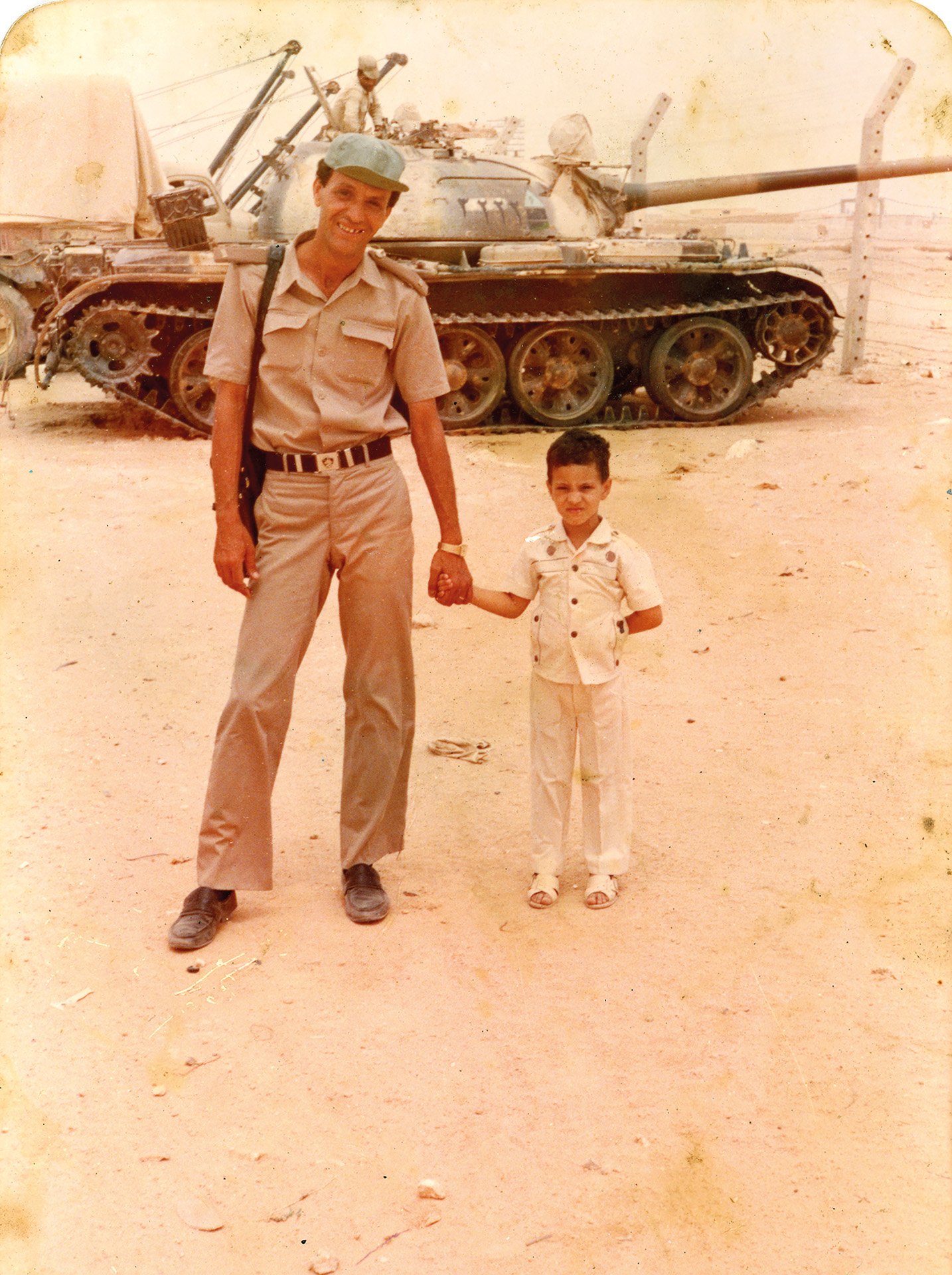

Mohamed: I remember standing outside my father’s darkroom door, listening to the soft clatter of trays and the rhythmic sound of water running. I wasn’t allowed inside, but I could smell the chemicals drifting through the house.

Emaho: What inspired you to pick up the camera for the first time, and how did those initial experiences shape your creative direction?

Mohamed: I picked up a camera for the first time much later than most people expect. Photography was always present in my childhood because of my father, but it was also a complicated space one I felt drawn to, yet kept at a distance. After my parents passed away, something shifted. I found myself returning to the memories I had tried to ignore: the darkroom, the smell of chemicals, the silence surrounding my father’s struggles. It was as if those memories were asking me to look again, more carefully this time.

Those early experiences shaped my creative direction by teaching me that photography, for me, is less about capturing what things look like, and more about revealing what they carry: silence, memory, tension, tenderness. From the beginning, the camera became a tool for processing emotion, for piecing together fragmented histories.

Emaho: How has your cultural background influenced the themes and stories you choose to explore through your photographs?

Mohamed: My cultural background shapes almost everything I photograph, often in ways I only fully understand later. Growing up between Egypt and the UK and now being rooted in Wales has meant living with a constant sense of in-between-ness. That feeling of belonging everywhere and nowhere at once has naturally become a thread that runs through my work.

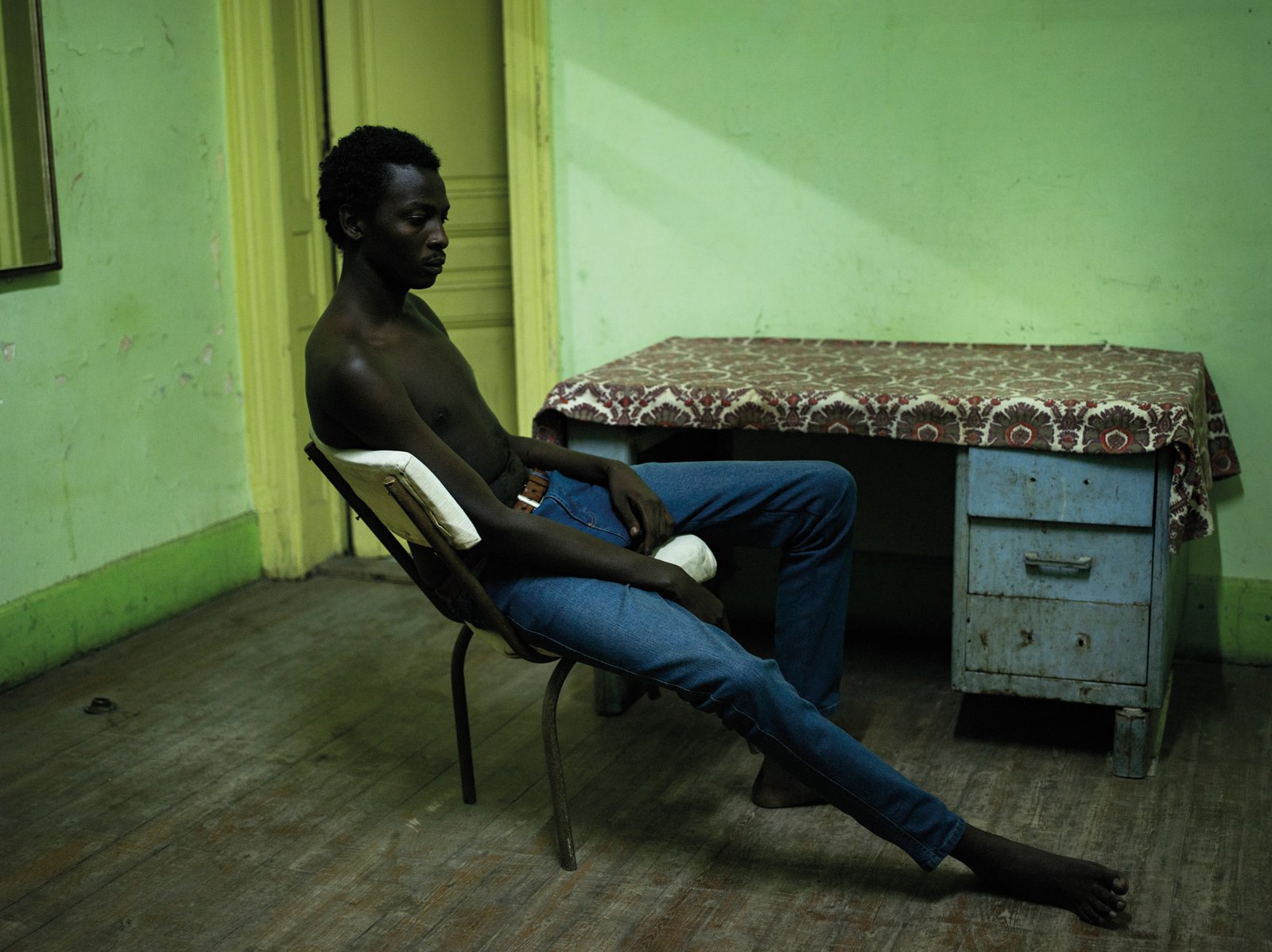

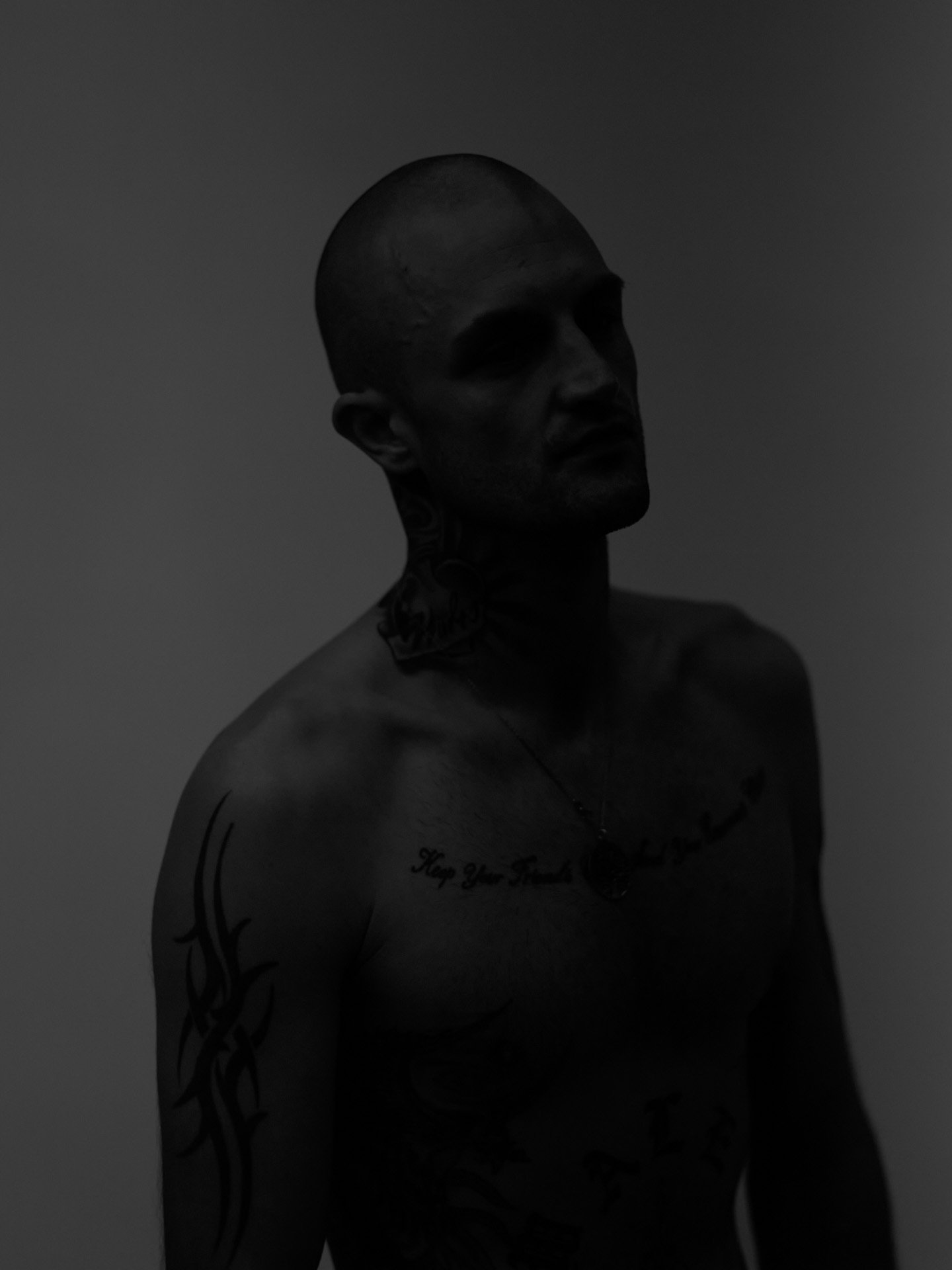

In Egypt, I inherited a world shaped by family, tradition, and unspoken emotional codes. There’s a depth of poetry, symbolism, and memory in Egyptian culture that I carry with me, even in the way I look at light, gesture, or silence. At the same time, living in the UK exposed me to different ways of understanding identity, vulnerability, and masculinity and I’ve often felt the tension between these two cultural worlds.

Because of this, I’m drawn to themes like displacement, inherited trauma, family histories, and the quiet complexities of migration. I’m interested in the stories that sit beneath the surface: the things people carry but rarely articulate. My photographs often reflect that layered perspective: part documentary, part emotional archaeology.

Emaho: In what ways has photography helped you reflect on and express your identity, experiences of migration, and sense of belonging?

Mohamed: Photography has become one of the few places where I can hold all the different parts of myself at once: my identity, my experiences of migration, and the shifting question of where I belong.

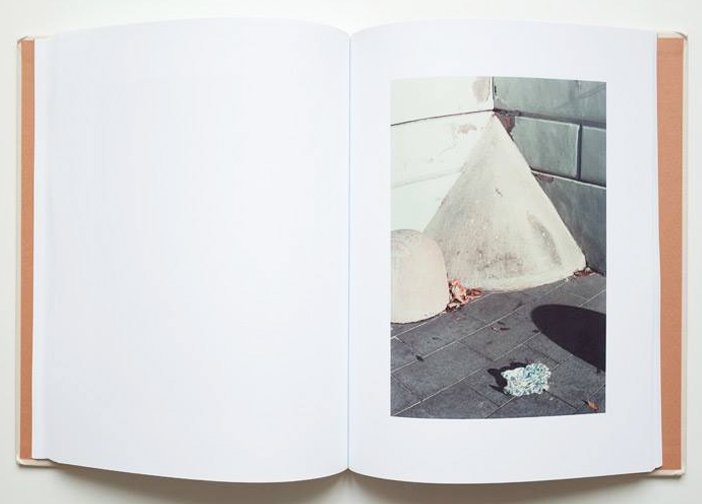

Emaho: Can you tell us about the process behind your photobook “Our Hidden Room”? What motivated you to turn personal history into a published work?

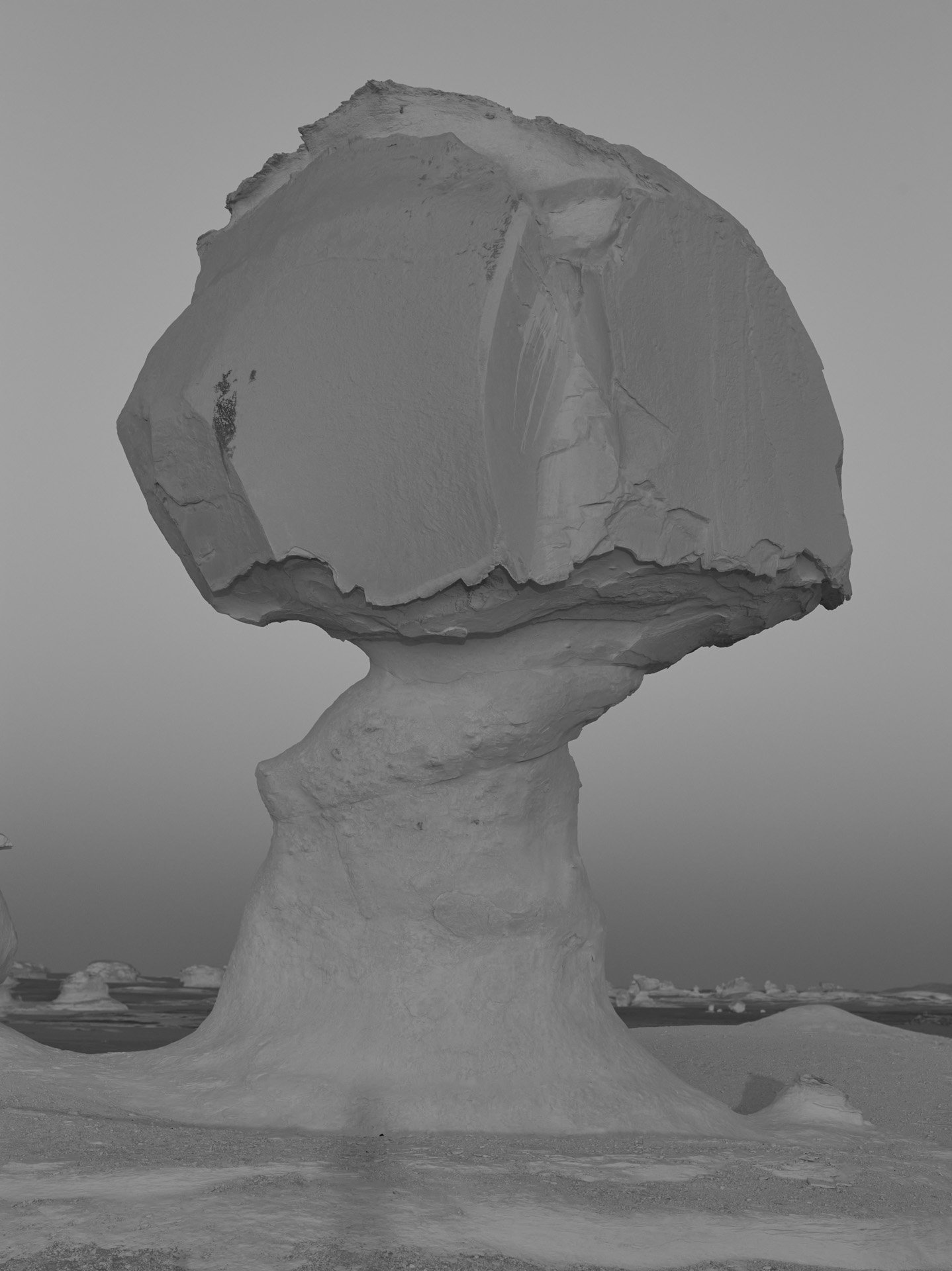

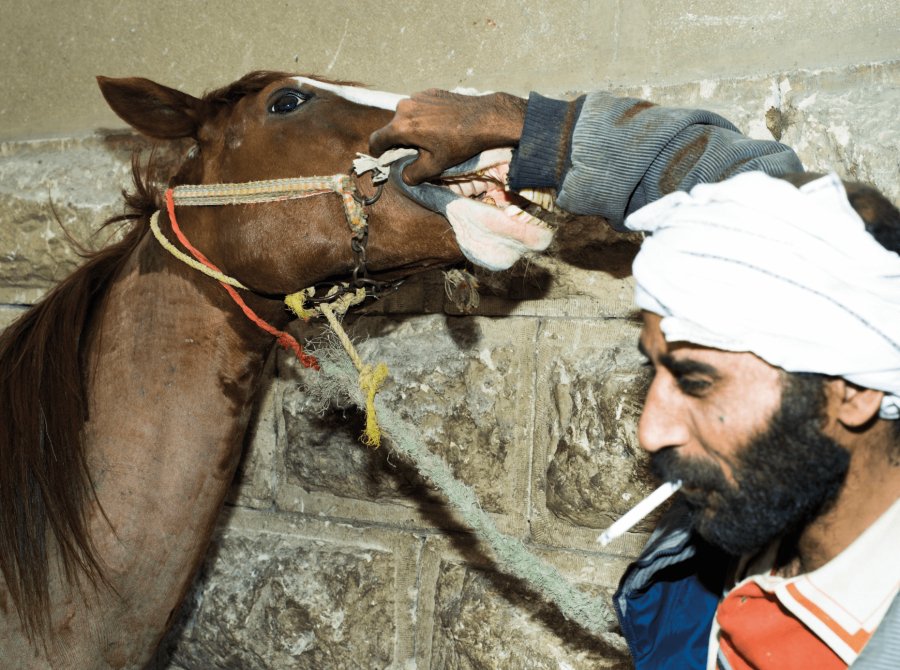

Mohamed: The process of creating Our Hidden Room was slow, emotional, and very instinctive. It wasn’t something I planned to turn into a photobook at first — it began simply as a way for me to confront memories I had avoided for years. I started by photographing small details that reminded me of my father: the quality of light on a wall, the texture of an empty room, objects that carried a quiet emotional weight. Alongside the images, I wrote fragments of memory, questions, and reflections. It became a dialogue between the past and the present.

The motivation to publish came from recognising that my personal history wasn’t only mine. So many people carry similar stories of fathers they couldn’t fully understand, of inherited silence, of mental illness that shaped families in ways no one talked about. Publishing the book was my way of opening that door, transforming something private into something that might resonate with others.

Turning it into a photobook allowed me to create a physical space where these themes of memory, trauma, masculinity, and love could exist together. It was a way of giving form to something that had lived inside me for decades, and of saying: this story is difficult, but it matters.

From a broader perspective, the stigma surrounding mental illness often stems from fear, misunderstanding, and cultural silence. In many communities, mental health is rarely spoken about openly. It’s often seen as a weakness, something shameful or private, rather than a human reality that affects individuals and families in complex ways. That silence can be devastating. It isolates people who are suffering and prevents them from seeking help or being met with compassion.

Emaho: What were the emotional and technical challenges you faced while reconstructing your father’s archive and weaving it into your photobook?

Mohamed: Our Hidden Room processes trauma by transforming personal pain into creative expression by turning silence into dialogue and memory into meaning. For me, making this work was a way of revisiting experiences that had long been buried: the confusion of growing up with a parent who was both loving and unreachable, the shame surrounding his mental illness, and the unresolved grief after his death.

The process felt like piecing together a story without all the chapters. But that incompleteness became part of the book, a reflection of the gaps and silences in our relationship.

The most difficult part of making Our Hidden Room was confronting the emotions I had spent years avoiding. The process forced me to return to painful memories the confusion of my childhood, my father’s unpredictable behaviour, and the silence that surrounded his mental illness and eventual death. Revisiting those moments through photographs and writing meant reliving the sense of loss, guilt, and unanswered questions that I had carried with me for so long.

Emaho: How do you decide which images make it into your photobooks, and what story do you aim for the final edit to convey?

Mohamed: When I’m editing a photobook, I don’t think in terms of “best” images, but in terms of emotional truth. I choose photographs that feel honest, that carry a certain tension, or that reflect the emotional landscape I’m trying to articulate.

With Our Hidden Room, the final edit aimed to convey a sense of searching a movement between memory, loss, and rediscovery. I wanted the narrative to feel intimate but open enough that others could see themselves in it.

Emaho: What role do memory and nostalgia play in your visual storytelling and bookmaking process?

Mohamed: In bookmaking, I use memory almost as a structural tool. It allows the work to move between clarity and ambiguity, between what is known and what is felt. The book becomes a space where memory can breathe, expand, and contradict itself.

Emaho: How have audiences in Egypt and abroad responded to your photobooks, especially “Our Hidden Room”? What impact has their feedback had on you as an artist?

Mohamed: The response has been surprisingly emotional, both in Egypt and abroad. Many people have told me that the book reminded them of their own fathers, or of family silences they’ve never spoken about. In Egypt, especially, people reacted to the cultural context of the unspoken rules around masculinity, mental health, and privacy. It opened conversations that often stay hidden.

Emaho: Looking forward, are there new themes, personal milestones, or photobook ideas you hope to explore in your future work?

Mohamed: I’m interested in exploring themes of fatherhood, lineage, and how masculinity changes across generations. I’m also drawn to stories of migration within Wales, especially within diasporic communities, and how identity forms in places that are geographically familiar but culturally complex.

I see future photobooks that blend portraiture, landscapes, and writing expanding the dialogue between personal memory and collective histories.

In many ways, I feel like I’m just beginning to understand the stories I need to tell.

I hope viewers leave Our Hidden Room with a sense of quiet reflection and emotional honesty. This work isn’t about finding resolution, but about recognising the beauty and complexity that exist within love, pain, and memory. I want people to feel that it’s possible to look at difficult experiences not to fix them, but to understand them differently.

I hope the project encourages viewers to think about their own relationships, especially the ones marked by silence or misunderstanding. Many of us carry unspoken stories or unresolved emotions within our families. By sharing mine, I want to create space for others to see parts of themselves reflected, whether in the tenderness, the distance, or the longing.