U.S.A. –

In the ghostly Mojave Desert of Southern California, dead trees don’t stay dead for long. American artist Jeff Frost fuses time-lapse and stop-motion photography using the desert as his studio. Jeff teamed up with the Lincoln Motor Company to create ‘War Paint for Trees’, a short film centered on reimagining the old into something new, in this case trees. Jeff’s second film, ‘Flawed Symmetry of Prediction’ is comprised of over 40,000 still images, dissecting dimensions of time, space and reality. Jeff’s films permit the viewer a window into the arcane, a world of illusion where even the trees wear war paint. I caught up with Jeff to ask him about his work.

Emaho : What led you to your current work as an artist? Tell us about the path you have taken to get where you are and what you were doing earlier.

Since the third grade, I’ve always produced visual art in some form or another, but since I was twelve my dream was to be a musician. To that end I taught myself how to play guitar, bass drums, program synthesizers and I started taking piano lessons at the age of eight. I moved to the LA area, or at least I tried to, and wound up behind the Orange Curtain (Orange County), which was close enough. Our drummer once booked a gig at a private backyard party that not only paid in free drinks, but actual money. It was early days for that particular band, and we were thrilled until we showed up at the address and saw a giant inflatable jungle gym filled with children. We double checked the address and were horrified to realize that we were in the right place.

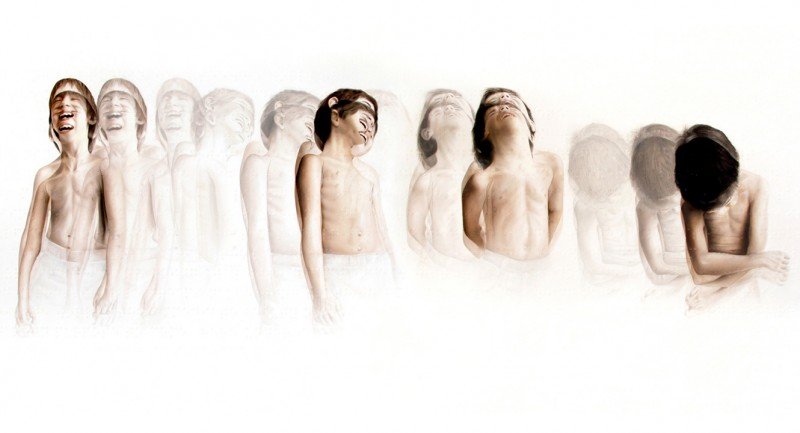

After setting up, the adults at the party repeatedly yelled at the menacing swarm of children occupying the pool in the backyard to, “Quiet down so the band can play!” Eventually, an acceptable level of clamor was reached, and we launched into our set of highly demented concept rock about multiple personality disorder, stalking, obsession and murder. The children were not impressed. Actually they were incredibly bored and went back to screaming and yelling. After one of the kids in the pool nailed our singer, Brandon, in the face with an inflatable pool toy we threw in the towel.

Thinking back on it now, that situation is pretty emblematic of my travels through the seedy underbelly of the LA rock world. I learned many ego- bruising lessons before deciding that I had had enough. I quit all my bands and went back to school for photography about five years ago, and although I had always taken artistic photographs, I knew almost nothing at the technical end of photography. I didn’t even know how to shoot on manual settings.

Emaho : You grew up near a Native American Reservation in Utah. What was this like? Did this kind of environment have any impact on the sort of work you are producing? What are your main influences?

The town I grew up in was extremely isolated and small, with a population of just under 2,000. The area is so incredibly rich visually, and so incredibly oppressive, religiously (at least as a teenager), that it couldn’t help but influence me in many ways. One of my main influences was my grandpa, Alfred (or “Alf”), who went on 50-mile hikes into his 80s, alone in the wilderness. He also loved taking me with him on shorter treks, and taught me to drive a stick shift at the ripe old age of 12. He had an incredible sense of spontaneity, adventure and mischievousness. Alf was a shining example to everyone who knew him.

As for the reservation, the Native Americans who lived there where shoved into the least desirable plots of land in the desert, and when someone found a natural resource there they were then shoved into another even less desirable spot. Not many people know this, but to this very day the United States government has not honored one single treaty with the Native Americans.

My dad was a farmer in the area, and hired several Navaho workers over a number of years. One was named, Luke, who would occasionally go on benders and take my dad’s old orange truck off to the reservation for a few days before returning. Luke was a hilarious and tragic figure. His stories about life on the reservation sounded like something out of a third world country or a different time. They were filled with violence, poverty and humor. Even though my parents were religious and conservative they put up with the benders because they knew Luke had a good heart.

This question is actually bringing back a lot of memories. And anger. The way we have treated Native Americans as a country and as a people is clearly awful. What can you expect with a country that still celebrates their genocide on Thanksgiving Day?

In many ways growing up near the reservation was a perfect distilled example of a minority living as the other. I remember years when it was particularly hot, and many Native Americans simply perished since few of their houses had air-conditioning.

There were years when insect infestations, which affected people in the area with modern houses very little, drove Native Americans from their homes (which were little more than shacks in the desert, sometimes without power or running water). The reservation is a tough place in every way. It’s the unfortunate result of years of oppression, lack of education and a feedback loop of prejudice from the outside. Conditions get worse on the reservation, the people there become increasingly dysfunctional, and then the people on the outside point at the situation and make judgments. Yet every new age asshole wants to claim they’re 1/12th Cherokee on their mom’s side. Can you imagine if people started doing that with another race? Look at me, I’m 1/12th Canadian! Isn’t that great? I’m cooler now; more spiritually credible… right?

Emaho : The Lincoln Motor Project selects artists to re-imagine the familiar into something new and exciting for their “Hello, Again” initiative. How did you first get involved with the company and how did you interpret the task at hand?

The staff at Vimeo really liked ‘Flawed Symmetry of Prediction, and passed it on to Lincoln. The “Hello Again” campaign was all about seeing something old as new again, and all of my work already fits that, so when Vimeo and Lincoln contacted me I pitched them on a project I had already been planning and they loved it. Working with them was a great experience.

Emaho : Clearly the use of time-lapses and stop-motion photography are perfect for your films, particularly for the footage of the Milky Way and the creation of optical illusions. It must be a very time-consuming process. What kind of challenges are you faced with?

The challenge I run into the most is the financial challenge of scraping together enough money to finance constant trips to the deserts, but there are much more interesting challenges such as angry bees, angry neighbors and police officers.

For example, when shooting the final scene for ‘Flawed Symmetry’, I had to contend with an extremely aggressive nest of bees in the house I was painting. The bees would seek me out, despite the fact that I was far from the hive. Every time they stung me the area they hit would swell up like a balloon. This type of swelling had never happened to me before and I was worried that I’d developed an allergy.

When I made the final trip to make the moving shot where I circled around the house at the end, sure enough, a bee found me standing at the edge of the yard and lost his life stinging a non-threat. Bastard. My arm started swelling immediately, and I considered going to the hospital 15 miles down the road but I felt okay otherwise so I forged ahead. That shot wound up taking from 9pm until 6am, while my arm filled the sleeve jacket like a living sausage.

There’s also the challenge of going to a place with no road map. Once a film is finished the challenge becomes figuring out how it fits into the world and finding its audience, and that can be tough because no one really knows what to do with me including myself. If you figure me out, call me.

Emaho : The ‘behind-the-scenes’ documentary for War Paint sheds light on some of your artistic process, particularly the way you avoid CGI and the scoring of each film. Elaborate on the methods you use to make your films.

This is a moving target, because I get restless if I start doing things the same way too many times. I’ve realized that for me the idea of doing something incredibly well is a boring one. Of course, I want to produce high quality work, but more than that I want to experiment. I live for the surprises, which is probably something that really pulled me into time lapse to being with.

Sometimes, my ideas are the initial driving factor in creating work, as in ‘War Paint for Trees’; at other times I start working and the idea of what I’m doing starts to emerge. Whenever I try to lock myself into a linear process I start shutting down, so I just don’t do it anymore. An appropriate analogue might be found in my musician days. Sometimes my songs would start with a lyric; some would start with a bass line or beat. Some would even start as a concept. I tried creating from every angle I could think of, and in many ways I have a similar approach now. Sometimes I even create two parts of what will wind up being the same thing in tandem without knowing if they’ll ever work together.

Emaho : Both ‘War Paint for Trees’ and your other film ‘The Flawed Symmetry of Prediction’ have been selected as Vimeo’s staff pick-of-the-week. What themes do you think run throughout your body of work? What impression do you think your audience is left with?

Those two works have fairly different themes in my mind, but the common thread running through both is a sense of the unknown. Maybe even the unknowable. This is not a reference to mysticism; it’s a reference to science, which is far stranger than mysticism. I often wonder if we’re simply not equipped, neurologically speaking, to comprehend the complexities of existence. I’m not sure why, but I both love and hate the idea of an unknowable question. The paradox that we can even ask a question that might be unknowable is quite the motherfucker.

The impressions people get seem to fall into two main categories: one group reacts with wonder, beauty and mystery, and the other with fear, distrust and paranoia. It’s a strange dichotomy.

Video Credits – Jeff Frost, Vimeo

Emaho : You have been described as an artist who “sifts through the visual dregs of places and people who once were”. How do you go about choosing your locations? Are there specific visual elements that you are looking for?

No, there really aren’t. It used to be that I looked for a room with a window that had another world outside of it that you could become absorbed in, but I’ve been expanding on that and pushing into unknown territories. Although, there are certain practical considerations such as assessing whether anyone actually cares about the property, can I work here for several days without attracting attention, etc.

Alf used to take me up into the hills at random looking for ancient ruins, and we almost always found something interesting. I like to let the road and the desert take me where it may. The planning part is just getting out the door with the cameras and packing the cooler.

Emaho : I have read that you squat in abandoned buildings in the deserts whilst looking for locations to shoot. Tell us about this experience. In the behind-the-scenes film you have said that you feel most happy when in the desert by yourself. You also speak of the importance of having a dialogue with your environment. Did you encounter anything strange whilst in the desert?

Encountering strange things in the desert is a given. One day I was exploring a remote stretch of I-10, which runs east/west, eventually running into Phoenix, AZ. I turned off the freeway and set out on a county road determined to push deep into the barren mountain territory south of the interstate.

I immediately ran into two things. A gigantic prison complex the size of a small town, and a forest service sign with the cheery admonition, “Explore your public lands!” The sign had an illustrated map with several roads crisscrossing through the desert. I picked one named “Gasline Rd” and went on my way. Six hours later, after having traversed many miles of bumpy dirt roads, I realized that I didn’t have enough gas to go back the way I had come. My plan had been to pop out on the south side of the mountain range all along, which would put me in one of my favourite stomping grounds, the Salton Sea, but I had no idea it was going to be this long a drive. Several hours after that with no end in sight, I started getting worried. Finally I came to a bluff overlooking what appeared to be a change in terrain. There were numerous rusted hulls of boats abandoned out there, but I knew I was still pretty far from my destination.

Then I saw what appeared to be a well-manicured firing range right along the road. I drove right up to it and noticed something strange: a giant rusted tank with one of its metal tracks lying in the desert sand halfway off the wheels. I started to get the feeling that I shouldn’t be there and looked up. Littering the horizon were more tanks and all manner of old military vehicles, some in twisted scrap heaps of metal. The tank was riddled with thousands and thousands of bullet holes. I looked down and saw thousands of exploded bombshells littering the ground. I definitely was not supposed to be there. After briefly flirting with the idea of staying anyway, I decided I better get the hell out before I started to look more like the tank.

It took a long time to find my way out, but with the needle on E I finally made my way out to the main road. Later that night I ran into a border patrol officer who turned out to be best friends with someone I knew from my hometown in Utah. He told me to avoid the mountain ranges I had just spent the entire day in because people involved in the illegal trafficking of humans and drugs went through there. He told me they had a habit of ramming anyone they saw on the road, shooting them and taking their vehicle.

I made a mental note not to go exploring in those particular hills again.

Emaho : You have recently released the first half of your film ‘Modern Ruin: Black Hole’. This appears to be your most ambitious work yet. How did you go about capturing the footage of the riots in this film?

Last summer in the middle of a warm June day I heard two gunshots right outside my window. There was a children’s party just down the street, and many people were out and about. Apparently the police had shot a man running from them in the leg. When he went down on his knees they shot him in the back of the head. He was unarmed.

Later that night the neighbourhood was protesting on the corner. The police came back, shot many people in the crowd with rubber bullets and released a K9 unit, which ran straight for a woman holding an infant. The man who stepped in between the two wound up with a mauled arm. After that things went completely crazy. 10 days of rioting followed. Every time I stepped out my door there were burning dumpsters, helicopters, protestors and a dozen news vans. It got so bad that the police took a page out of the LA riots playbook and disappeared. Dumpsters were left to burn on a major five-lane thoroughfare for hours and hours while traffic whizzed by.

I climbed on my landlord’s roof immediately and started time-lapsing the events both day and night. With one camera on the roof I was free to join in the protests and photograph the crowd. At one point the police returned and fired more rubber bullets in my direction. When the riots moved to city hall I followed with my camera. Everyone just assumed I was part of the press so I went wherever I wanted and shot everything I could.

Emaho : You have set up a kickstarter to help fund the second half of the project ‘Modern Ruin: White Hole’. How are you finding this process?

It’s quite a bit more work and stress than I thought it would be, but it has given me a chance to learn many new things such as putting together the pitch video and coming up with rewards that are interesting and fun. In fact, one of the rewards has even given me an idea for a series of paintings I’ve already started experimenting with.

It’s also given me a chance to find out if anyone is really interested in what I’m doing and meet some amazing new friends. If I had it to do over again I would do all kinds of things differently, but I’m happy with where the project is headed.

Emaho : Is there anywhere else in the world you would you like to go in order to pursue your vision?

Yes, and that place is everywhere. I have a bucket list that only seems to get bigger. A few examples range from the Namib Desert to the Crooked Forest in Poland to forgotten Soviet monuments in Bulgaria, not to mention all the abandoned asylums in Europe. I’ve spent my whole life listening to what other people wanted to put into my mind in regards to the outside world, but now I want to go see it for myself.

Art & Culture Interviewed by Max Grobe