Emaho: You were born in Tehran and spent your childhood during the Iran–Iraq War. What early memories from that period shaped the way you perceive people, conflict, and the fragility of daily life?

Sahar: I was born in Tehran, and my earliest memories are inseparable from the atmosphere of the Iran–Iraq War. The constant tension, sirens, and sudden disruptions of daily life shaped an early understanding of fragility and impermanence. Even as a child, I sensed that safety was temporary. Watching people navigate fear, silence, and resilience side by side deeply influenced my sensitivity to emotional shifts and unspoken realities. These experiences formed the foundation of my later focus on instability, inner tension, and the vulnerability of human existence.

Emaho: What are your earliest memories of art? When did painting begin to feel like a real language for you—something capable of expressing feelings or experiences you could not articulate verbally?

Sahar: I was born into a home whose walls were covered with paintings by my grandfather, Houshang Pezeshknia. During a period marked by my parents’ separation, those images became a refuge for me. What may have appeared as imitation to others was, for me, a way of finding safety and calm. Through these early encounters, painting became a real language—one that allowed me to express emotions that could not yet be articulated through words.

Emaho: Over the years, your work has explored themes such as separation, isolation, and loss of identity. How did these ideas first surface in your paintings, and in what ways have they matured or shifted as your life changed?

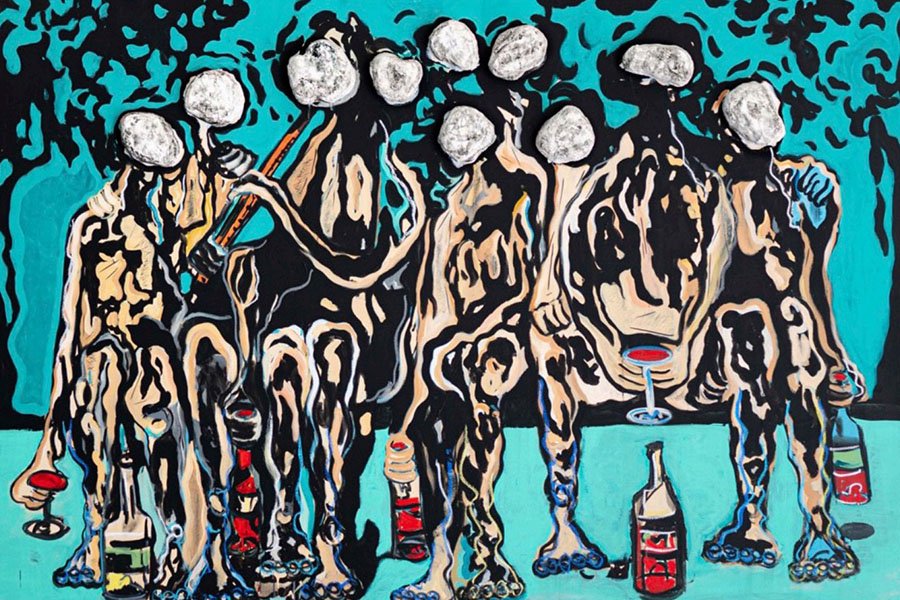

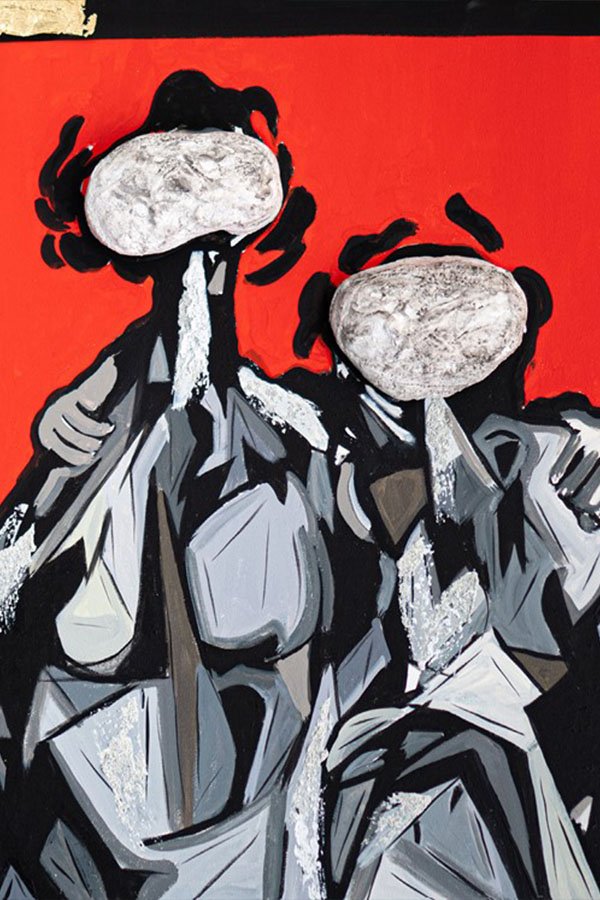

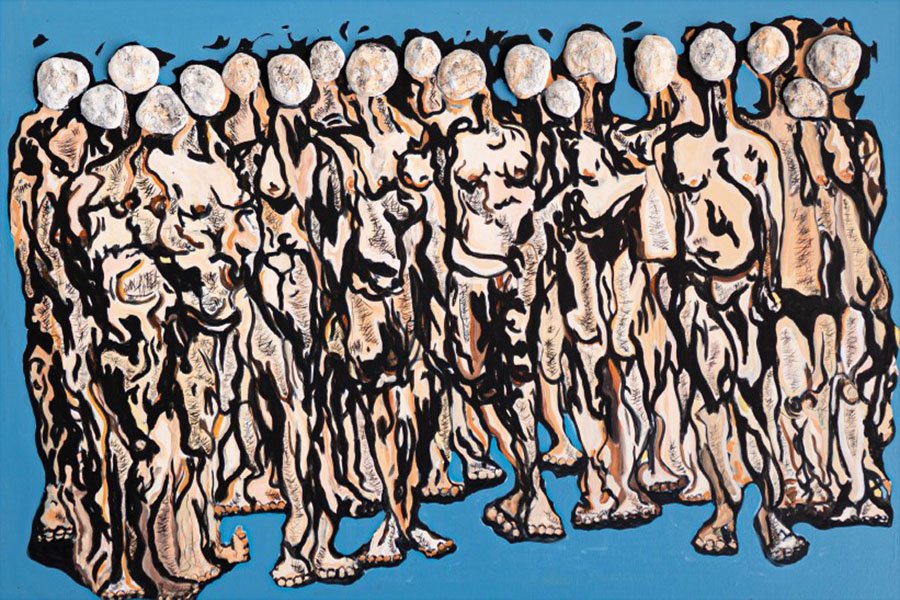

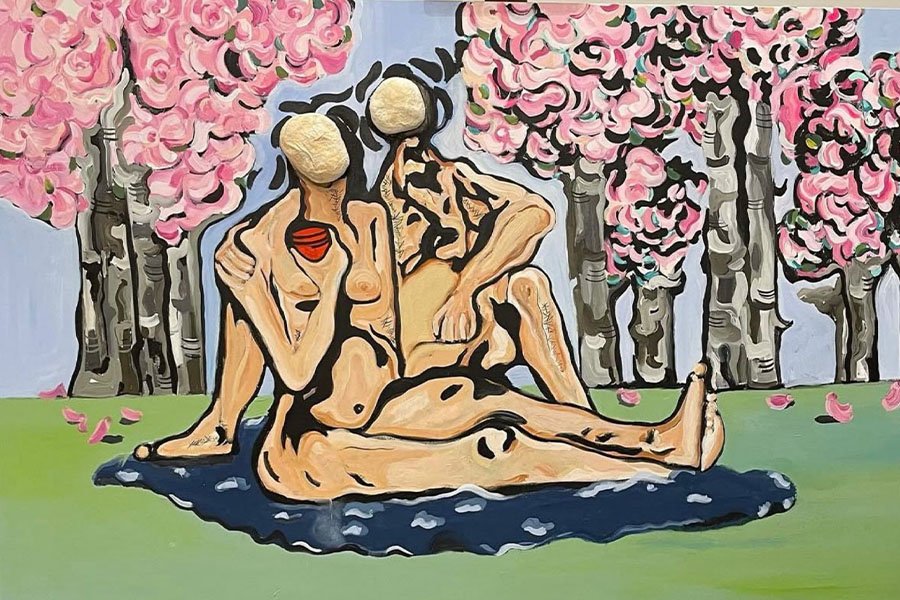

Sahar: Themes of separation, isolation, and fractured identity emerged organically in my work long before they became conscious concepts. Initially, they appeared through suspended bodies, unstable figures, and compressed spaces. Over time, these themes evolved beyond the personal and took on a broader human dimension. Identity in my work is fluid, constantly shaped by pressure, absence, and transition.

Emaho: You emigrated to Germany as a teenager and now live in North America. How has this movement across geographies – Tehran, Germany, and your current home – shaped your visual language, sensibilities, and subject matter?

Sahar: Living between Tehran, Germany, Vancouver, and later Dubai profoundly shaped my visual language. Each place represents a distinct psychological experience. Experiences such as war, migration, and later the COVID period led me to consciously avoid defining facial features in my figures. The absence of faces is not decorative, but a response to lived experiences of dislocation and identity loss.

Emaho: Which artists, writers, or artistic movements have influenced your painterly approach? Are there particular practices or philosophies that continue to inform how you construct a portrait or build a composition?

Sahar: My grandfather’s socially engaged paintings deeply shaped my understanding of art as a carrier of social narrative. Jackson Pollock influenced my sense of freedom and movement, while Picasso’s continuous reinvention inspired my approach to risk and change. These influences function as spiritual references rather than formal templates.

Emaho: Your exhibition Turbulent at Shirin Art Gallery in Tehran remains one of your defining early shows. What core ideas drove that body of work, and how did audiences in Tehran interpret the emotional intensity behind those pieces?

Sahar: My exhibition Turbulent at Shirin Art Gallery in Tehran was one of the defining early moments of my practice. The core idea centered on the paradox of being present among people while experiencing deep inner solitude. Audiences strongly connected with the emotional intensity of the exhibition, recognizing it as a shared human experience.

Emaho: You have exhibited in Tehran, Abu Dhabi, Miami, New York, and other cities. Which exhibitions or moments felt like true turning points for you, whether in terms of artistic direction, recognition, or personal growth?

Sahar: The three exhibitions I held in New York were true turning points for me. In each of them, I worked with concepts that I had deeply lived rather than merely imagined. These bodies of work clarified my visual language and helped define my artistic direction with greater consciousness and precision.

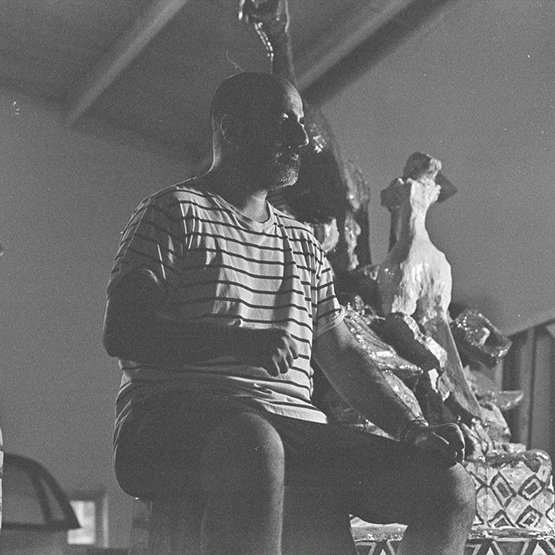

Emaho: You’ve mentioned that you only paint when you are in very intense emotional states. How does this affect your studio rhythm, decision-making, and the rawness or urgency that appears in the finished work?

Sahar: I only paint when I am in very intense emotional states. This makes my studio rhythm irregular, marked by long pauses followed by periods of concentrated urgency. Decisions are intuitive and immediate, giving the finished works a raw and compressed intensity that cannot be replicated outside those moments.

Emaho: As an artist who has lived through war, migration, and displacement, what responsibility – if any – do you feel when presenting a new series? And looking ahead, what themes, formats, or scales are you excited to explore in the next phase of your practice?

Sahar: I understand responsibility as honesty toward lived experience rather than delivering direct messages. Looking ahead, I am interested in working more with the body, space, and scale, creating works that physically and psychologically engage the viewer. The next phase of my practice is about deepening, not abandoning, the concerns I have lived with for years.

Art work by Sahar Khalkhalian