Emaho: Can you tell us about your early life and how it influenced your journey as an artist?

Pooya: I was born in a unique family and grew up in a specific atmosphere. My father, the late Amir Hossein Aryanpour (1925–2001), was a pioneering Iranian lexicographer and sociologist, and had a great impact as a writer, translator, philosopher, and literary figure during his lifetime. My paternal uncle, Amir Ashraf Aryanpour (1938–2022), was an influential musicologist, musician, researcher, writer, and university professor. Prior to being admitted to Fine Arts high school, I was homeschooled until my mid-teenage years, going through an exceptional early education. The very notion of education, in its collective and organized form, took shape for me while I was being introduced to the academic world of painting after entering art school. I was deeply passionate about painting, and I found the setting of art school quite nurturing, especially since I had not been exposed to primary education.

Emaho: What motivated you to pursue a career in art, and who were your early inspirations?

Pooya: In my earlier years, learning about the very ability to feed my imagination through movement, poetry, music, sound, and literature was deeply inspiring. Since the very beginning, all of these motivated me to pursue an artistic career and practice.

Emaho: Your work spans various mediums and themes. Which body of work do you consider most important or personally significant? Why?

Pooya: To me, there is a purity and immediacy in painting that creates a closer bond between the artist and the practice. I feel my deepest and most enduring connection remains with painting.

Emaho: How do you personally define art, and what role does it play in your life?

Pooya: I do not see art as an act separate from my life; I am situated within it, making it an intrinsic part of my existence.

Emaho: Art in Iran and the Middle East faces unique challenges and opportunities. What is your perspective on the current state of the art scene there?

Pooya: The art scene here is vibrant and full of passion. A dominant sense of excitement prevails, and it is the social movements and activities that fundamentally shape the concepts and titles utilized by artists.

Emaho: Several of your pieces are part of prestigious collections. What does this recognition mean to you and your practice?

Pooya: While it is certainly a source of encouragement to have my work in prestigious collections, I consider it neither sufficient nor ultimately important to my practice. My focus remains on the work itself and the ongoing development of my artistic language.

Emaho: In what ways do you think your cultural background influences your artistic voice and expression?

Pooya: On one hand, a unique historical experience, and on the other, the exceptional geographical position of Iran, consciously and unconsciously contribute to forging a distinctive cultural language in my work. My artistic expression is intrinsically linked to this deep-rooted cultural and historical context.

Emaho: How do you balance traditional aspects of Iranian/Middle Eastern art with contemporary global art conversations?

Pooya: The beauty of creation lies precisely at this intersection. It is the sensitive and joyful point where you, or your work, react to this convergence of traditional depth and contemporary global discourse. This tension is where innovation and meaningful dialogue emerge.

Emaho: Technology is rapidly changing how art is created and experienced. What are your thoughts on the future of art in this digital age?

Pooya: I find the rapid advancement of technology in art to be interesting rather than frightening. It represents a new frontier, and we must wait and see how it ultimately shapes the future of artistic practice and experience.

Emaho: How do you integrate or respond to emerging technologies and digital platforms in your own work, if at all?

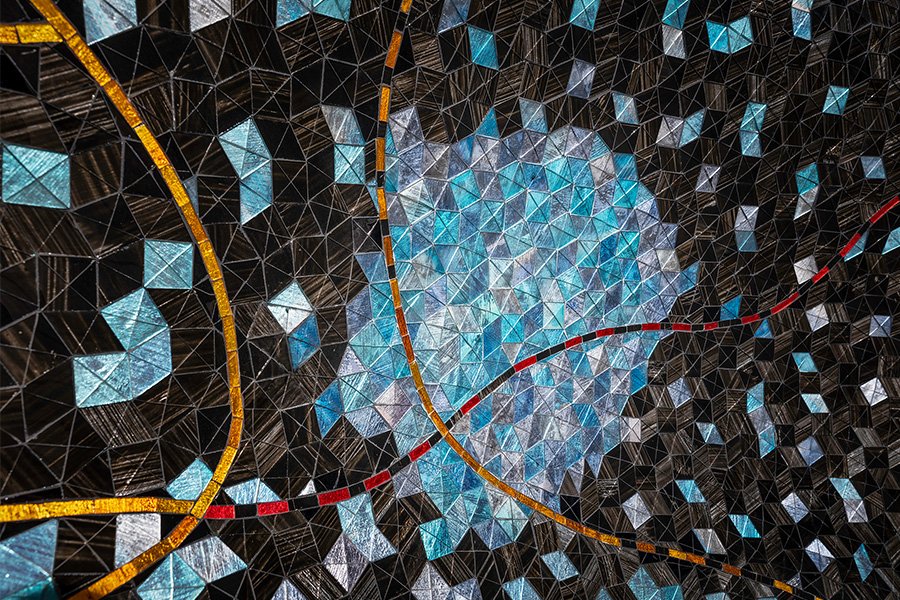

Pooya: Emerging technologies sometimes serve as an aid in my work. For instance, digital simulation was key in transforming my initial sketches for larger installations into manipulable computer models, providing ample potential for experimentation. Fundamentally, a new tool can often generate a new idea, thus opening up new avenues for creative exploration and expression.

Emaho: What advice would you give to young artists from the Middle East trying to navigate the global art world today?

Pooya: I would advise them to insist on audacity and courage in their practice. These qualities are essential for an artist to break through and forge a unique path in the complex global art world.

Emaho: Can you share an experience or project that you feel was a turning point in your artistic career?

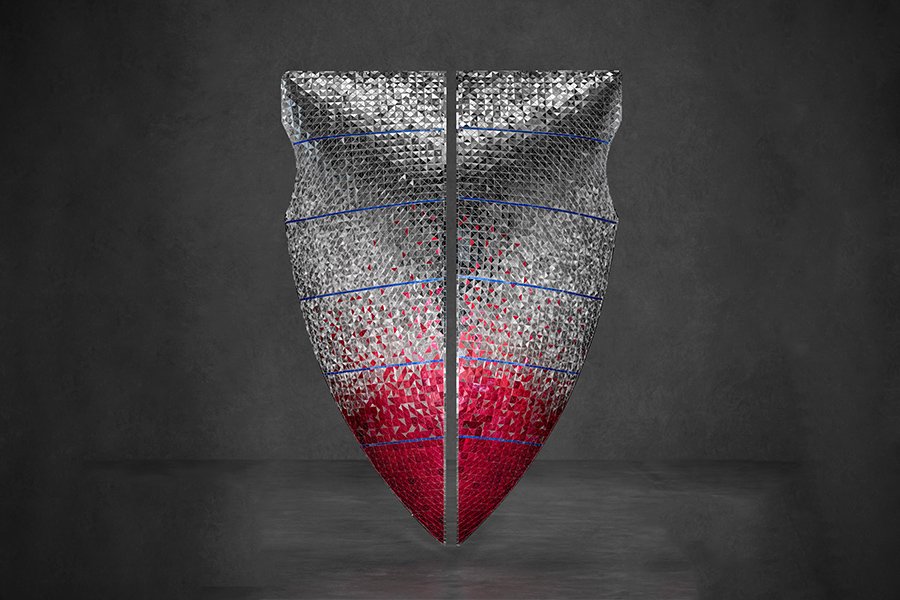

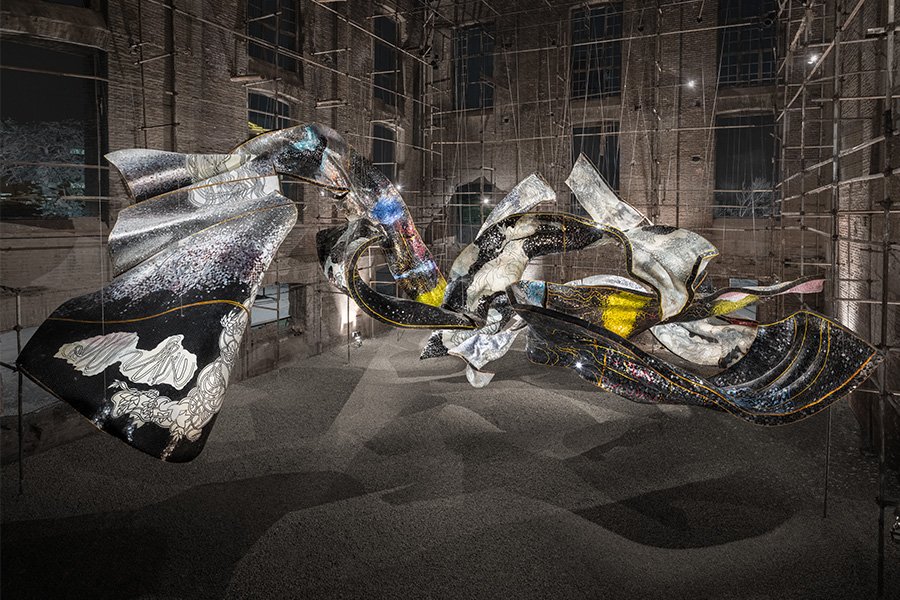

Pooya: I can name two distinct periods: The Red Period (paintings) and Gone with the Wind (a site-specific installation at the site of the defunct Kahrizak Sugar Factory). The Red Period was significant not for the works themselves, but for the profound state of mind I experienced. Following a great loss, everything became small in my view. The primary outcome was the courage I gained, which allowed me to work with great power and conviction. Gone with the Wind, on the other hand, was a culmination of years of exploring concepts of incompleteness, ephemerality, and instability, manifesting in a large-scale installation and site-specific work.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what exciting artistic directions or themes are you eager to explore next?

Pooya: After extensive, multi-year projects like Gone with the Wind, I have been in a period of new studies and discoveries. My next artistic direction will emerge from abstractly rethinking the conceptual threads of my previous work, likely focusing on a new series of studies that examines the idea of a place after a massive phase of destruction and desolation.

Art work by Pooya Aryanpour