Japan –

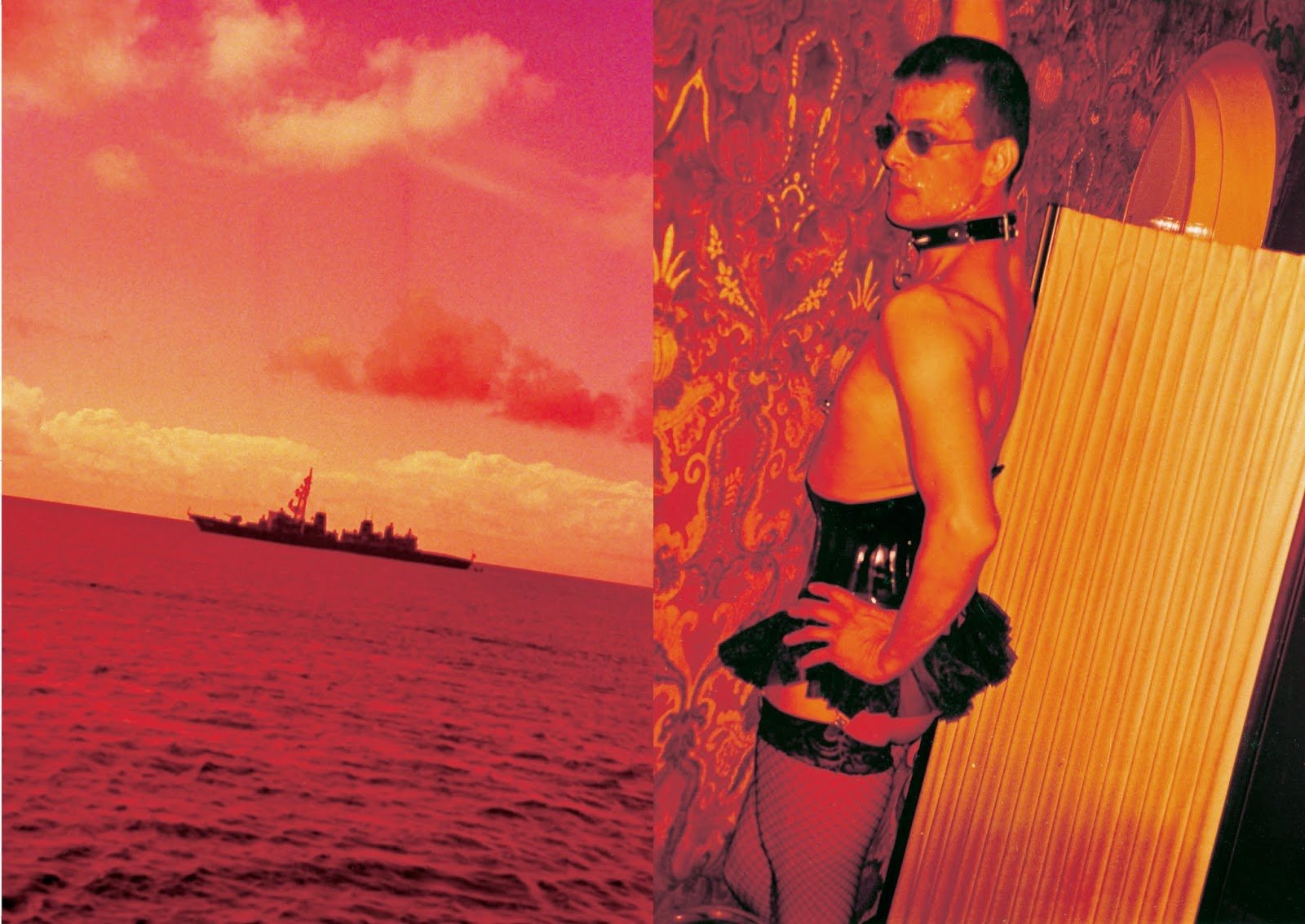

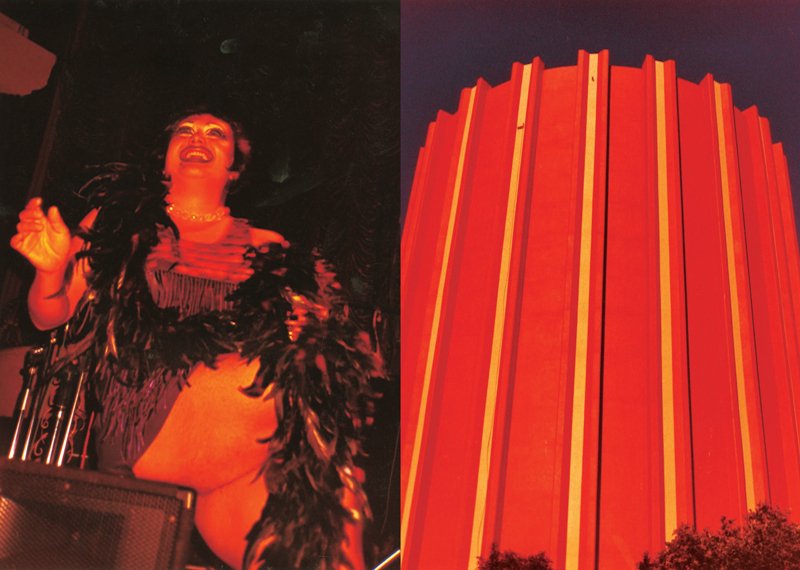

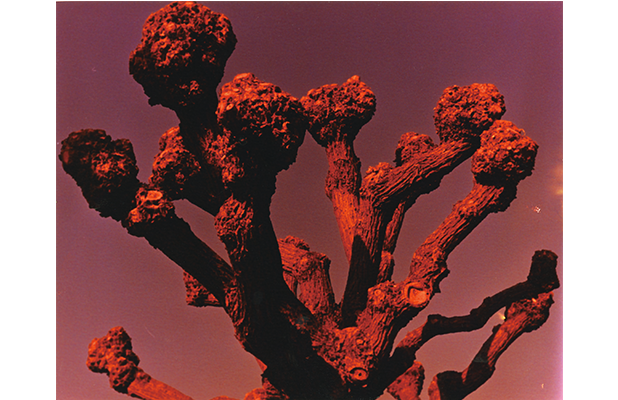

Momo Okabe’s photographs depict the bare situation. Be it the sexual act, a wasteland, or the wake of a tsunami, the images Okabe presents speak directly, without device. There is a vitality to her practice, so much so that she notes that the process of constructing her book Bible saved her, nominated for Kassel Photobook Award 2014 by Manik Katyal. Responsiveness, but measured, aware, consummate, marks the event of Okabe’s photos. How does the body keen to a touch? When the water runs, how does the land react? What is love in an age of bodily dissociation, and how to bring our union with flesh back? Momo Okabe’s eye finds the necessary elements of uncertain, contingent existence, which she carries with care for others to see, knowing that a breath will scatter them.

Your work is extremely personal and the camera often seems to be an inseparable part of your own experiences. What does photography mean to you? What drew you to photography from such a young age?

When I was in junior high school, my father caused a problem at work and my family had to struggle with him seriously. He became mentally ill gradually from stress and my family started to function no longer. It was a tough time for me since I was still very young and I felt like I didn’t have any means to protect myself from society where people always tried to attack me as vicious enemies. However, I discovered that everything looked perfect and beautiful when I looked at the world though a camera. I felt as if I could accept and overcome the difficult experiences as far as I stayed in the world (observed through a camera). Because of photography and because of the action of taking a photo, I don’t give up living. I believe photography has helped me to cope with the difficult situations that happen in life.

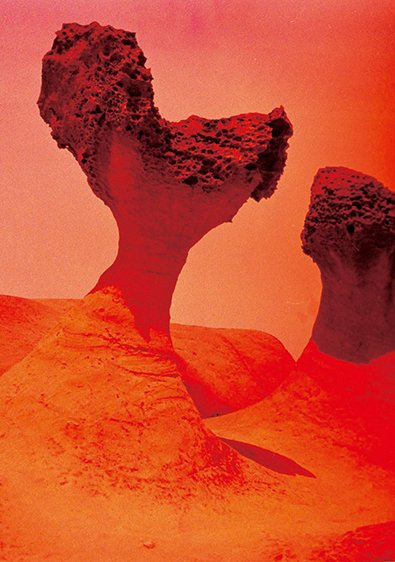

You use color in your work in a very distinct and beautiful way. Your colors seem emotional and surreal at the same time. How did you come across this style of photographing?

A. For me, scenery/the world looks just that way. This color is made from my work in the darkroom at my house. I believe it is very important that I stay there alone and go through this time consuming process of making my work.

Your book Unseen/ Tsunami was a collaborative work with Kohey Kanno, where you both photographed your personal lives against the backdrop of the Fukoshima Tsunami. How did this collaboration come about and how did the tragedy of the tsunami affect how the work was created?

“Tsunami” was based on my personal experiences around the time the 3.11 tragedy occurred in Japan. When it happened, I was working in an office in Tokyo, and I went to my co-worker’s place for evacuation. We watched the TV program together and could not talk when we saw news from the

Sendai area where everything was burned. We were both confused and somehow awakened by this since we strongly realized that, without choice, we were now actually alive when many people were dying from this horrible disaster. I noticed that both terror and desire of life aroused from inside of me, and both feelings were equally powerful to me. A few days after the earthquake, I stayed home because of a risk of radiation outside, and I struggled with my uneasy feelings in my room. I truly wanted to destroy everything I had. I had physiologically stayed away from making “sex” in general and especially sexual contact with men and had a strong hated feeling about them for a long time. But I decided to sleep with my co-worker who went through the same experience together that day, and we both became accomplices and agreed on taking pictures of this act. I think when disaster happened, all Japanese people were very confused and we all became true to ourselves (as human beings). When I talked to Kanno-san, my old classmate from the college, we shared the same feelings. I don’t think we could report or document the tragedy of the disaster appropriately as photographers. All we could do is to show a feeling that we could not help from reality that we happened to still be alive. “Tsunami” was the work that I made to express my own personal desire as a person.

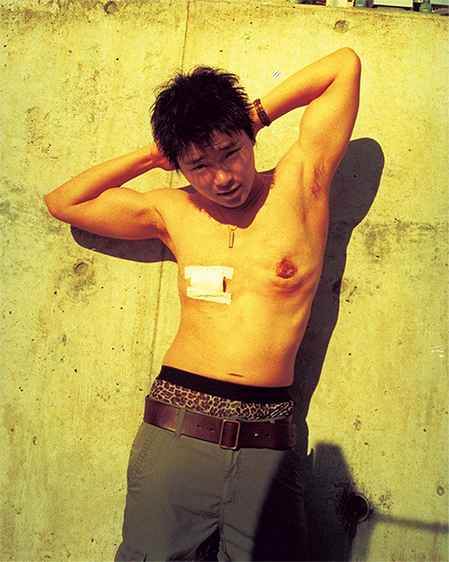

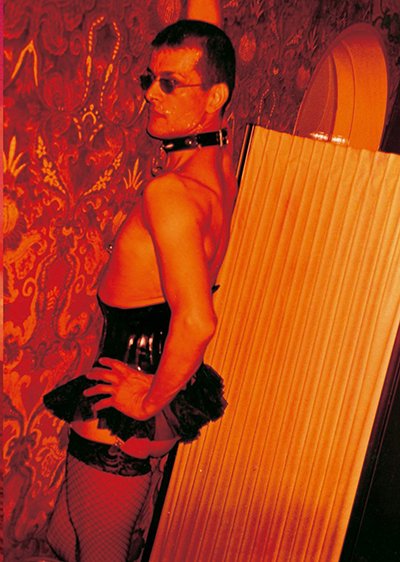

Your first US monograph Dildo dealt with your intense relationship with two lovers who were dealing with issues of gender identity. Your book was also a limited hand made edition. What was the process of putting your work into a book? How important was it for you that your book be hand made and only into a small set.

“Dildo” was like my private diary with my partners at that time and it was very intimate, although it was not open to the world. Since it was such a precious memory that I wanted to hold by myself as a secret, making “Dildo” by hand was important to me. It had to be hand-made, not machine-produced. If I had to make more than 50 copies, I would have been incredibly exhausted. 50 copies is as much affection as I could give to “Dildo”.

Your work has been widely acclaimed in Japan for over a decade (since being acclaimed by Nobuyoshi Araki in 1999 at the New Cosmos of Photography, it has received awards and special mentions in Japan in 2004, 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2013). Now your books Dildo and Bible are receiving attention globally. How has the reception been to your work on a global platform, and how has that experience changed the way you think of your books?

I have always taken pictures just for myself. It has been this way, and I will just make work when my memory/experience needs to become my work. I will not change my working style.

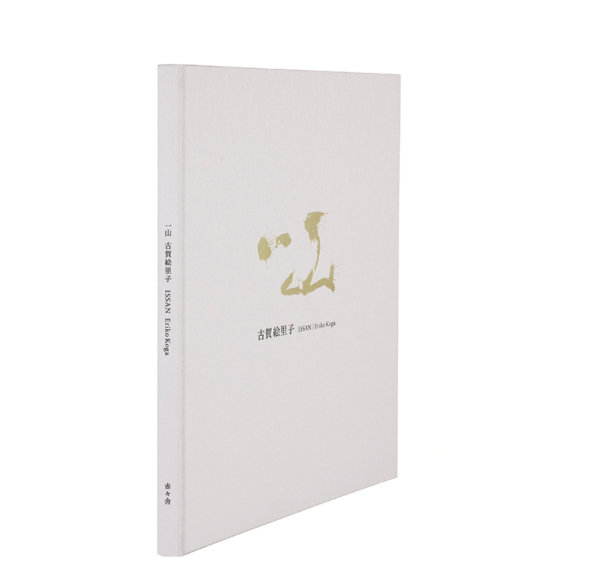

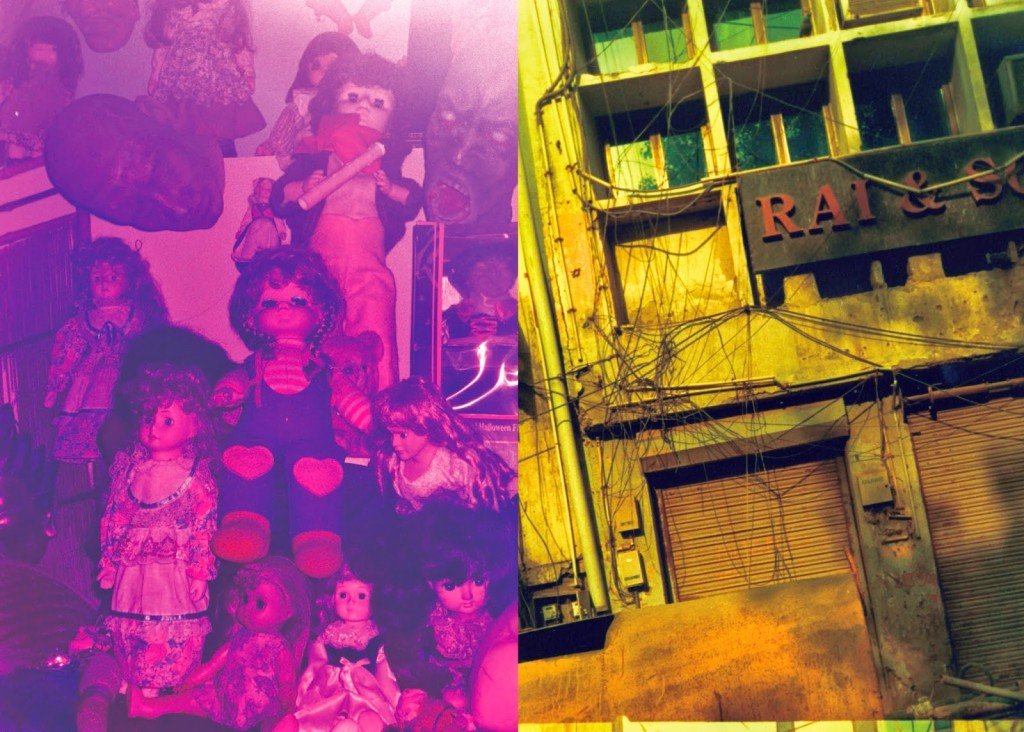

Your latest book Bible contains many previously unpublished photographs taken in Tokyo, Miyagi and India between 2008 and 2012. How did the edit of the book come about? Why did you choose to call it Bible?

I edited “Bible” by myself and put images almost perfectly chronologically. All the images came from my personal experiences and “Bible” is a result of my life for the last few years. I chose this title since I wanted to make it very special, final and definite for myself. When I was making the book, I realized that this project was saving me just like the Bible, and I thought that this title suited to my book.

Your work has a three dimensional richness, which is both emotional as well as visual. Your use of color makes your work atmospherically beautiful even at its most raw and painful. How do you achieve this surreal color palette in your work?

When I take a picture and make a print of my work, I don’t intentionally do it. I don’t like a “set-up” type of working style where everything needs to be prepared and directed in advance. Pure feelings only reside at the moment of emotion. I don’t think photography needs anything other than just to be beautiful. No other explanation is required. Therefore, I only print the colors the way I see the world as being.

Deeply emotional and personal subjects are often difficult to show and exhibit. Have you faced any sort of resistance to your work and its raw and honest subject matter?

I had an arguments with an organizer before when I was invited for the exhibition. I also had an experience that my book was removed from the shelves at bookstores. It is my personal belief that I can do anything I want as long as I don’t hurt anybody. So, I didn’t understand what was wrong with my work. I don’t have any concrete statement to fight against this so, I hope someone will explain to me when my work was considered to be bad or wrong.

I was told before that my work was created just from my personal curiosity. I was stunned by the fact that some people saw my work from such a narrow perspective. I believe that if you look at the work with your prejudiced mind, it looks just evil. On the other hand, if you open your mind and look at the work sincerely and purely, it appears just as beautiful as it is. I think photography is simple and it honestly expresses one’s/other’s minds. Therefore, I want to be honest when I take a picture.

When you are putting your work together, do you also imagine your audience? If so, what sort of audience do you want for your work?

I have always taken pictures just for myself. It has always been this way, and I will just make work when my memory/experience needs to become my work. I will not change my working style.

What do you hope to achieve with your books Dildo and Bible? How do you intend to take your work forward?

For Dildo, I took photos of my lovers, since I loved them very much and wanted to understand them better; it was about them, not about myself. For Bible, I took pictures of the people, places and things only when they really moved me. The portraits in Bible are people who had a very hard time before but stay strong and struggle to overcome their trauma and so on. I didn’t create Dildo or Bible to proclaim any political/social reform in society. For my next book, I want to make photography from my very strong emotion, and my next book must appear just like a family album.

You photographed in India as well as in Japan when you were working on Bible. How did you come to photograph in India? And what was the story connecting your experiences in India to the rest of your experience for Bible?

India appears to me just like a Shangri-La. I felt that everything was forgiven and life and death are very close to each other and both are welcomingly accepted. When I visited India, it certainly motivated and inspired my Bible project.

You mentioned that you chose the title Bible as you felt the project was saving you. How did you feel it was saving you, and was the experience of working on Bible cathartic for you?

I didn’t mean biblical when I mentioned “saved”. It happened internally as my absolute truth.

Do you feel that in some ways a lot of the world is not ready for work that is as honest and raw as you show it? Also, by creating such deeply intimate and personal work, do you wish to open up the world to being more aware and accepting of lives that don’t entirely conform to society?

My work reflects my thoughts and I took a lot of pictures relating to sex since I am most interested in sex and I find sex very mysterious. I must keep making work about sex till my wonder/quest for mystery is resolved. It is very understandable that everybody takes sex/sexuality in a different way. Therefore, I understand that not all people see what I am trying to achieve. That’s is OK. I just want to make work that is very true to myself.

岡部さんの作品は、とても個人的な体験から制作されて、

私が中学生の時に父が仕事である事件を起こし、

菅野恒平さんとの共作で、ダシュウッド・ブックスから”

岡部さんは、以前、荒木経惟さんから、

私はこれまで自分の為だけに写真を撮っていました。

最新作”bible”は、東京、宮城、インドで撮影され、

編集は全て自分で行っていますが、

バイブルというタイトルにしたのは、

岡部さんの作品は、

写真を撮る際やプリントする際に考えて意図的に制作はしません。

個人的な作品や、感情が強く出た作品は時として、

また、

私はこれまで自分の為だけに写真を撮っていました。

どんなことを期待して、バイブルとディルドを制作したのですか? 今後は、どのような作品を制作する予定ですか?

Dildoでは自分ではなく相手の事を好きで理解したいから写真

あなたが制作する作品のような、誠実で生々しい生(性)

Photography Interview by Manik Katyal