Saudi Arabia –

Hailing from a country fraught daily with controversy and oppression, Manal Al Dowayan has blazed into the Saudi art movement with an unprecedentedly vital voice. The 39-year-old has emblazoned a tone of both rebellion and serene contemplation upon the past, present and future of Saudi history and cultural preoccupation. From outlining vehement opposition to everyday injustice, to highlighting the most intimate cornices of an individual soul, Miss Al Dowayan has been standing at the helm of a new generation of female artists who transpose the particularities of their origins to a global understanding. She speaks with Emaho about the symbolism, essence and import of her art.

Emaho : Your work has dealt with both contemporary situations of strife and oppression, as well as personal revelation. Do you feel that photography lends your expressionistic motives an immediacy of representation?

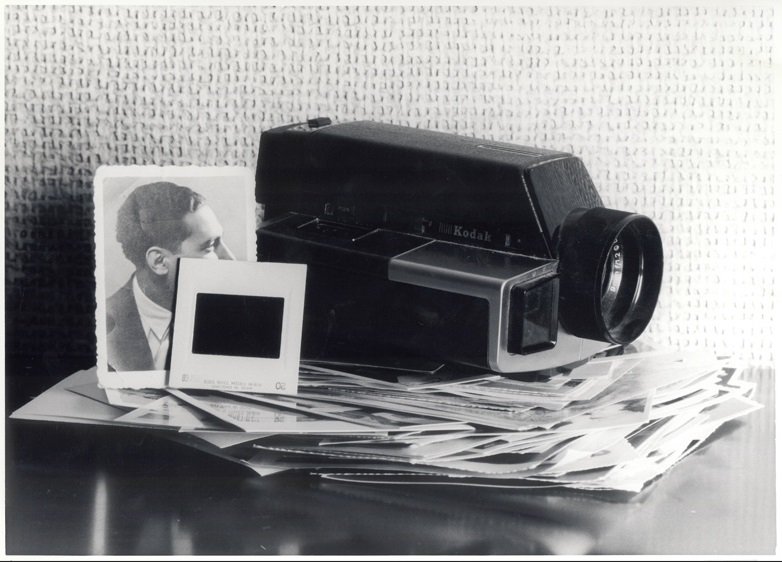

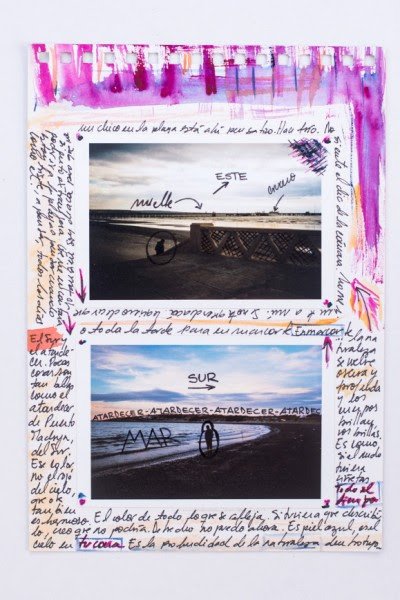

I continuously struggle between the different channels of representation for the concepts within my work. Although I mainly work in photography, spatial and textual artworks also play a large role in my practice. My earlier works were direct images with simple concepts, but over the years I started including layers of ink, silkscreen prints, neon and collage in my photographs, in an attempt to create multiple conversations in one work. I even got rid of frames and eliminated anything that stands between the artwork and the viewer. I then worked on large-scale installations that fill a space and create an experience. I also started using the written word, which is sometimes even more powerful than an image, because the imagination starts creating the image based on the text.

I am always in search of the all-encompassing moment that a person has when they interact with an artwork, so it is not simply about the visual representation; rather, it is about the emotional impact of the concept that formulates in the mind.

Emaho : Your work has indelibly highlighted the struggles of Saudi Arabian women, and in a lot of the photographs—such as those in the collection ‘Bound’—claustrophobia is a palpable element. However, in collections like ‘If I Forget You, Don’t Forget Me’, there is a certain degree of melancholy and nostalgia. Would you say that the sense of claustrophobia is declining because you feel hopeful, or do expressions of different sentiments simultaneously inhabit your collections?

I am constantly exploring the ideas of exclusion and belonging within the physical or the ethereal state of being. In both ‘Bound’ and the ‘If I Forget You, Don’t Forget Me’ series I discuss the idea of navigating imagined barriers and partitions. I focus on exclusion in the former collection and belonging in the latter.

Emaho : How often do you allow fear to feature in your work? Have you been significantly afraid of the repercussions of creating such radically opinionated work in a conservative milieu?

I have a fear of making bad art, but not of the imagined repercussions.

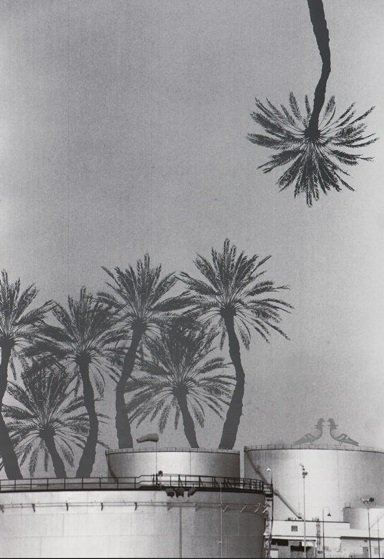

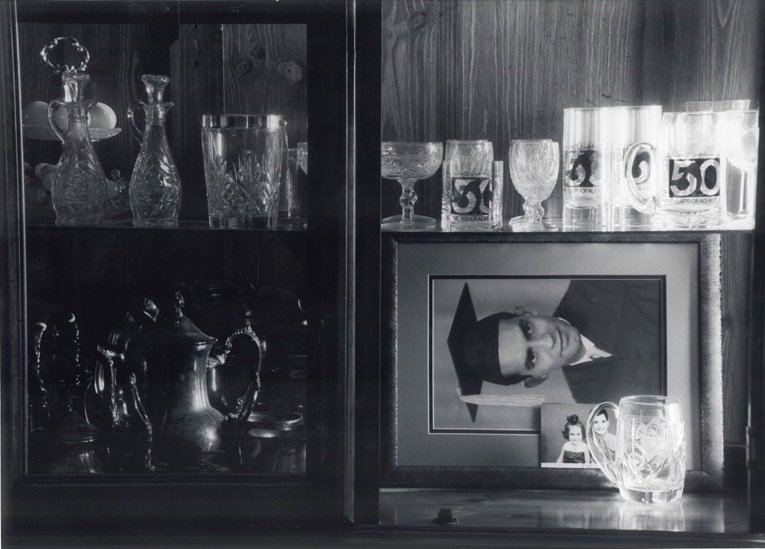

Najd, From the series If I Forget You Don’t Forget Me, 2012, Image Courtesy of Cuadro Gallery

Najd, From the series If I Forget You Don’t Forget Me, 2012, Image Courtesy of Cuadro Gallery

Emaho : In ‘Esmi (My Name)’, you assert the woman’s right to proclaim her name, and consequently her individual existence in Saudi Arabia. Would you say your interest in art and photography emerged from a similar desire to distinguish yourself?

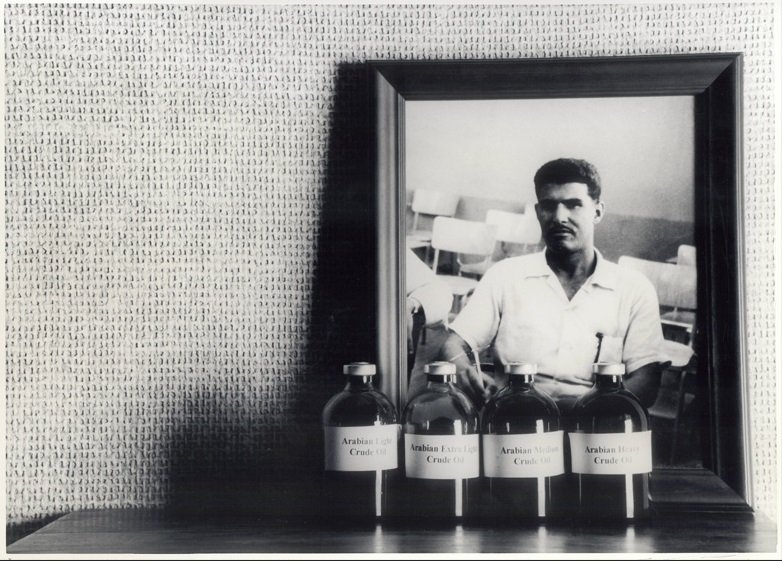

Not distinguish but preserve. I think it is human nature to preserve memories of oneself and memories of others. My struggle is not with the natural loss of memory but the intentional erasing of a story or the act of active forgetting. I look at visual images that are repeated over and over as deliberate acts of changing a story or, worse, creating new ones that are not real.

My work is all about capturing an image and being able to tell a story through the visual elements of artwork. I question the stories that are being written visually today, I worry about what is being documented and how it will be used tomorrow. I am constantly faced with the question of what is the true image of the Saudi Arabian woman? Who is she? And who is telling her story? Is it just the media images that feed into the world’s imagination and will eventually be the historical reference of who I am? Will I ever be represented in my natural state, rather than the images that are constantly filtered through different agencies and cultural rules? My name is being erased because of the shame of pronouncing it in public and my voice needs to be lowered so as to not offend … what remains of me?

When I worked on the participatory art work ‘Esmi’, it was a period where I became intrigued with the idea of disappearance and active forgetting. In my participatory artworks, ‘Suspended Together’ and ‘Esmi (My Name)’, I addressed my personal feelings about belonging by including women in the actual making of the artwork. I was absolutely energized by having a group of individuals interact with the artwork and contribute to the concept behind the work by simply agreeing to participate. So I had moved from the studio where I did not interact with anyone to a new paradigm where the concept moved from my head to the participants then into the artwork. Is inclusion the answer to belonging? Can art preserve and document? These are questions I have thought about for many years.

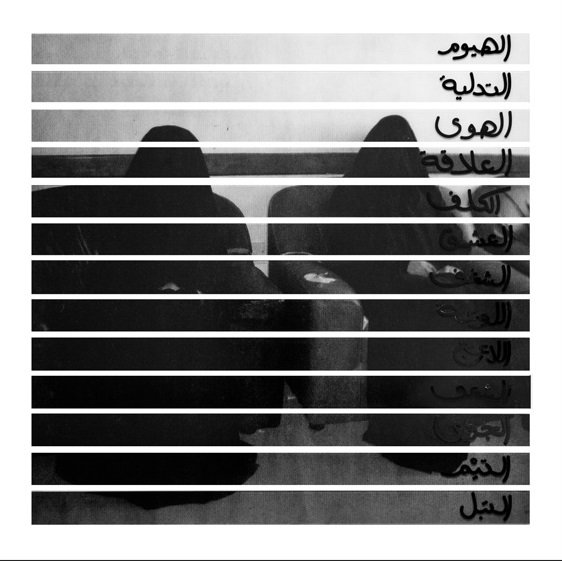

Emaho : ‘The State of Disappearance’ conflates word and image and enacts, as you state, “a tension between the power of the written word and the visual image“. Would you elucidate on this? Do you believe the two cannot be complementary?

Of course they can, but not in the context that I created, which was an intentional tension. Over the past few years I have collected images of women in my local daily newspaper. After a while it became clear to me that the veiled shapeless black ghosts that were in these media images were being repeated over and over again. I researched the impact of repetition on the human psyche and how acceptance through repetition is a dangerous human trait. I even found one image that was used eight times in the span of three months, different articles but the same image! All the images were of women in groups encouraging the idea of weakness through herding; all the women had no faces or human features like hands and feet. These images were intentionally removing humanity from the individuals they represented. Once humanity has been removed, then abuse and the acceptance of abuse become easier. I then introduced the synonyms of words traditionally linked to a woman—like ‘love’, ‘courage’, ‘happiness’, and ‘intelligence’—creating a struggle between the word and the images they lay on. They are awkwardly linked to each other, highlighting the negligence in how women are portrayed and the danger of continuously evoking this imagery.

Emaho : You often refer to works of Arabic literature, history, law, etc. Do you feel the need, in your work, to always place each individual photograph in a larger context?

History and literature are not context to me. They are an integral part of the artwork. I also include research notes, articles, and found photography and video in many of my projects. I always worry that in the quest to create art I become focused on the aesthetic and abandon the truth for the sake of order and elegance. I find the idea of simplifying very dangerous conceptually. Human nature wants pattern and pattern only appears in simplicity. I try to include many layers to my concepts and force myself out of the comfort of simplifying data, because simplicity does not mean clarity.

Art & Culture Interviewed by Shreya Bose