Bulgaria –

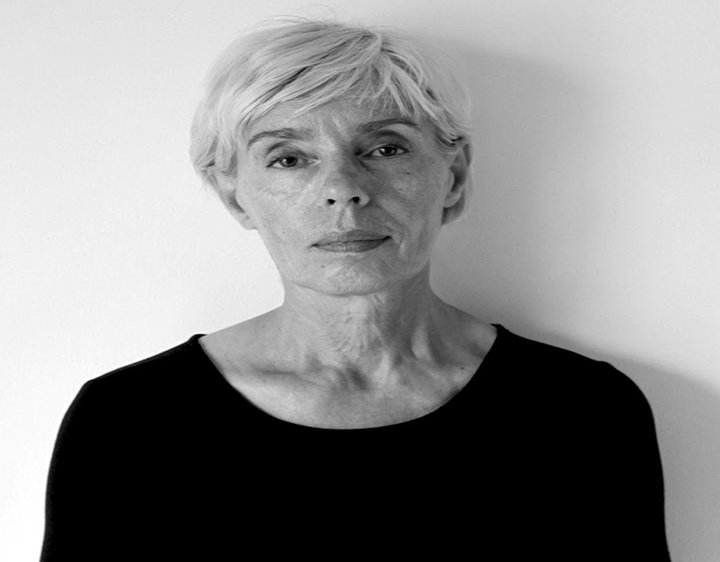

Emaho caught up with renowned Bulgarian photographer and founder of FotoEvidence, Svetlana Bachevanova to learn what it takes to tear down the Iron Curtains of ignorance.

Manik : What made you study photography and take it as profession later? What was your work as a medical photographer?

I became a medical photographer because I wanted to be a sculptor. My parents, who were doctors, wanted me to follow the family tradition and study medicine. I was 18 years old and my favourite book at this time was, “The Agony and Ecstasy” by Irving Stone, a biography of Michelangelo. I read this book again and again, trying to learn from his life how to become a sculptor. I thought it was very important to learn the structure of the human body. From the book, I learned that the best way to study anatomy is to do dissections. The only place I could do this was at the Medical University in Sofia, Bulgaria.

When I expressed my desire to work at the medical school my father helped me to find a position there as a photographer. His hope was that being around the medical school; I might change my mind and agree to study medicine. My hope was that once I was there I could sneak into some of the anatomy classes where students do dissections; which I did.

Before long, I realised that I didn’t have the temperament of a sculptor. It was too slow a process. But photography gave me almost instant results in the darkroom. My job at the medical academy was to document surgeries, experiments, photograph unusual skin diseases and micro photography. In my spare time I was portraying my family and people from the street. Photojournalism at this time in Bulgaria was purely communist propaganda and staged events. So instead I worked in art photography – nudes, conceptual photography etc. Eight years passed before I got my first real job as photojournalist in the anticommunist newspaper Demokrazia.

Memories from family album

Manik : How did the idea of forming FotoEvidence come about?

I was born in Bulgaria, in the dark age of Communism. There, I witnessed and experienced the worst of living under oppression: the disappearance of people with dissenting political views; people sent to prison for asking political questions; parents who escaped the country leaving their children behind; the oppression of ethnic Turks and Roma, the silencing of intellectuals; and the forced conversion of religious minorities. I first became a human rights activist to protect religious minorities during a period of persecution.

In 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I become chief photographer for the first anticommunist newspaper in Bulgaria, “Democracy”. There I photographed and wrote about the struggle to wrest my country from the Communists; a struggle that took many years in Bulgaria. My life work has always been focused on human rights and the freedom of expression.

Coffin with the body of a Muslim man, tortured and castrated by the Serbian militia- Kosovo.

I founded FotoEvidence to continue my life work of using photography to fight oppression and expose human rights violations. I seek to help photographers who work to document human rights violations and fight for justice, so the story of repression that happened in my country and to my friends will never happen again.

FotoEvidence is media without censorship; a place where documentary projects unlikely be published in other media, because they don’t cover a hot topic or a hot spot; can find a home. The images we publish are not always pretty or well composed but we publish them because they often reflect life the way it is. I believe that the harm we do to each other in wars and conflicts should not be veiled but shown with its real face, so the consequences of our actions become clear and visible. Eventually maybe we can learn from our actions and try not to repeat them.

Founding FotoEvidence was my idea but the realisation of the project would not be possible without the support of several dedicated likeminded people who contributed their skills, including David Stuart, Regina Monfort, Jim Wintner and our programmer Jack Lovell. Also individual financial contributors help make it possible. We are always looking for support of either skills or money.

Cofins with dead bodies in a warehouse

Manik : What is the FotoEvidence Book Award?

The annual FotoEvidence Book Award recognises a documentary photographer whose project demonstrates courage and commitment in addressing a violation of human rights, a significant injustice or an assault on human dignity. The selected project is published in a book, as part of a series of FotoEvidence books. The winner and four finalists are exhibited in New York each autumn.

I know it is every photographer’s dream to publish their work in a book. So I created a book award to help photographers get their work published. I enjoy working with the winners on the design and layout of their book and curating the book award exhibit for all the finalists.

Many photographers that FotoEvidence has recognised have gone on to win other awards. The 2011 FotoEvidence finalist Majid Saeedi (Iran) went on to win the Robert F. Kennedy Courage Award for journalists in 2012. Finalist Boniface Mwangi (Kenya) was recognised as a 2012 Prince Claus Fellow and 2012 finalist Vlad Sokhin saw his project, “Crying Meri”, adopted by the United Nations for an educational campaign about violence against women in Papua New Guinea.

My goal in creating the FotoEvidence Book Award was to help and support documentary photographers whose work focuses on social justice. A couple of selected photographers have behaved badly, taking the support FotoEvidence provided and then not even communicating with us, as though they were owed this recognition. But for the most part, I have had a great experience meeting and working with other documentary photographers working on social justice around the world.

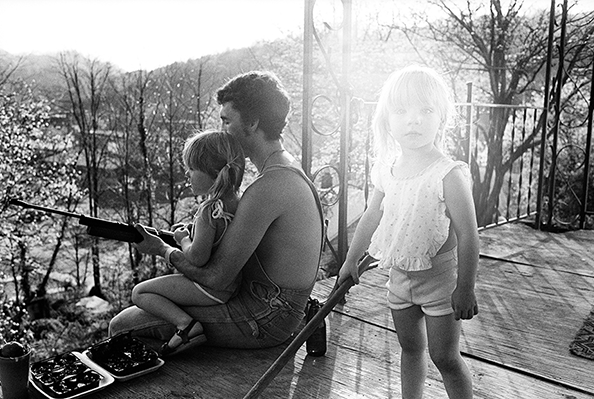

Men with Pow wow traditional costume and gun dancing a war dance during the opening of the Veteran’s pow wow in Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. There is a deep warrior tradition among the Sioux The Veterans pow wow honored veterans from World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the invasion of Panama and both U.S. wars against Iraq.

Manik : What was your experience like being the official photographer of the first democratically elected PM of Bulgaria?

I was the photographer selected from the newspaper and later from the Bulgarian National News Agency to travel with the Prime Minister and cover his meetings with other heads of states. I had the privilege to spend time with one of the bravest and brightest men in our new democratic country. It was a time when Bulgaria needed recognition, after 50 years under communist rule, so we travelled a lot. Some of these meetings were historic, like the meeting at the White House between the U. S. President George Bush and Prime Minister Filip Dimtrov; the first ever between heads of state from these two countries.

I remember, during this visit, I waited in the press room of the White House for the meeting to begin and somebody came to ask who the photographer with the Prime Minister of Bulgaria was. The man, who turned out to be Bush’s photographer David Valdez, offered kindly to take me to a tour in the White House while waiting for the meeting to begin. We walked around and finally entered one of the rooms. There was this desk a few meters from me and a man was writing at the desk. It took me few moments to realise that this was the President of United States. He saw us and came to shake my hand. I was speechless.

Eileen Janis is holding a portrait of her mother and father depicted in an old Lakota way. Author of the painting is Leonard Peltier who did it in the prison where he is detained after the killing of two FBI agents at the Wounded Knee occupation in 1973. Eileen mother is been American Indian Movement member and close friend to Leonard Peltier.

Manik : While shooting the war in Kosovo for the Bulgarian News Agency you witnessed a lot of bloodshed, what was it like capturing aggression, pain, and sorrow?

The war in Kosovo was my first war. I was young and passionate about the injustice towards the Muslim population in there. On the other side of the conflict were the communists; Milosevic and the Tigers of Arkan. There was no way for me to have a balanced view in this situation. I was on the side of the powerless.

With the help of a dear and brave friend of mine, who was driving our car, I was able to go places that the Serbian press centre in Pristina would never allow me to go. I had the misfortune of witnessing and photographing what the Serbian militia did to the Muslim men from a small village near Pristina. They were captured, tortured, castrated and left to die. We found them in a warehouse where the bodies were kept for five or six days before the mass burial.

The people from the village were eager to show us the evidence. I decided to hide my films under one of the tires of the car, in case somebody stopped us. I loaded my cameras with new film. A few minutes after we left the village our car was pulled off from the road by Arkan’s soldiers. My cameras and the car were checked for film. They took the empty film I had just loaded. Back in Pristina I developed the photographs and later in the day those images where broadcasted by my agency to AP, France Press, EPA and other agencies. Somebody told me that these images were the first clear evidence of Serbian atrocities to Muslims in Kosovo. I was glad that I was able to help expose these atrocities and show the world the true face of the communist regime in former Yugoslavia. I like to think that those images had something to do with how the world reacted to the conflict in Kosovo.

Donka and her son in their room. Many young Tinsmiths brides experience unhappiness after being married to men they donâtâ like. Divorce is out of the question and they have to live, raising child after child, cooking meals and cleaning house. Most of the men travel around the country to find work and are rarely at home.

Manik : Your images from Kosovo are extremely up close and personal. How did you manage that?

I followed the politics in former Yugoslavia and Kosovo from the beginning of the conflict. I speak the language and know the culture. I was coming from another ruined-by- communism country. All these factors played a positive role in the way I was accepted as a photographer.

Three just maried couples celebrating with traditional folk dance during the clan courtship gathering near the village of Mogila, Stara Zagora area. At the Horse Easter day every year young girls and boys from the Tinsmith gypsy clan gathered together to meet each other. Several wannabe-brides joined in, showing their eagerness to be married. Two of this couples met hours before they married in a traditional ceremony with no legal status.

Manik : You participated in an illegal democratic movement in communist Bulgaria. Tell us about your experiences and the book you published about it – “The Street”.

I consider this time the happiest time in my life. If you never experienced living under communist regime it is hard to imagine the hope and the relief when we learned about the fall of the Berlin Wall. At this time I was already a member of the first underground or illegal committee for defending human rights in Bulgaria. During our meetings we talked about what could be done to free political prisoners, to help the Turkish population facing forced name changes and conversion into Christianity.

On November 10th 1989 the men who had destroyed the country over the last 45 years were removed from power. The people were on the streets demanding free elections. Within a month we were publishing the first anticommunist newspaper and thousands lined the streets to buy its first issue. I was there in the printing house when the first page of the newspaper Demokrazia came to the world.

The time was dynamic and often we just stayed at the newspaper overnight so as not to miss some very important event. It was a time of hope and new beginning. I was glad that I played an active part while documenting this important change to my country. I put all the images together in a book, “The Street”. I believe that this is the only photo book published from these times in Bulgaria. The text and the poems where written by a dear friend of mine and political dissident Edwin Sugarev.

People gathered to support the democratic forces in Sofia, Bulgaria after the fall of the communist regime, demanding for free elections. Bulgaria was ruled by communist governments for 45 years – the worst in the history of the country.

Manik : Does covering conflicts through photojournalism help overcome the issues in question?

I spent half of my life living in a country where information about politics from outside of the Iron Curtain was the most valuable piece of information we could get. We listened late at night to radio stations like BBC and Voice of America and this was the only connection we had with the rest of the world. The communist propaganda broadcasted only news about the success of the regime and never about poverty, violations of human rights and political prisoners. One day a friend of mine shared that his father died in the concentration camp at Belene, one of the most notorious camps in the country. I was shocked and asked my mother if this could be true. She lowered her voice and told me, “Never, never talk about this outside of our house; Even the walls have ears.” If our neighbours heard our conversation they might report us to the police just for talking about the camps.

So, yes, I believe that if a photojournalist can document evidence of social injustice, of violations of human dignity and rights and spread it to the world, this will make it more difficult for the oppressors to continue what they do. FotoEvidence has a feature: Report Injustice Now, where photographers and citizens can publish documentation of oppression they witness. If we feel there is injustice, we publish them, even if the quality of the photographs is not excellent. Here the activism plays a more important role than the quality the photography.

FotoEvidence has visitors from 178 countries from around the world but not even one from Cuba,Iran or China. Why are the rulers of these countries not opening the world for their citizens? The answer is, they are afraid. Once you see the light, once you taste freedom there is no way back to the dark. And the oppressors know this.

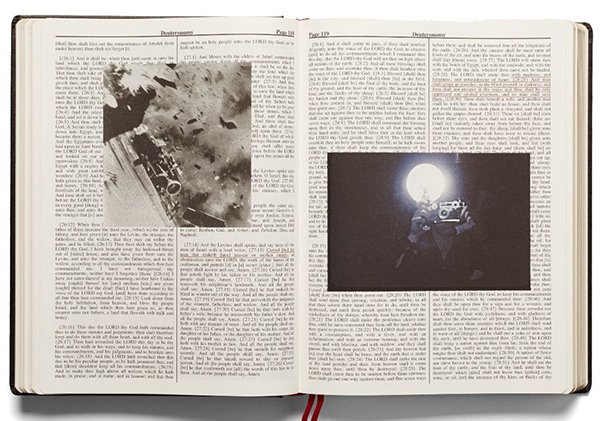

Should we publish photography that shows the consequences of war and conflicts, photographs of wounded or dead soldiers? It seems that this is a big debate in the media community. My answer to these questions is “yes”; we should publish them without worry about the aesthetic of the image. If the people of a country are free to exercise their democracy and vote for governments and presidents who push the state into endless war with thousands of young men and women who died for an unclear cause, the people of this country should see images of these deaths on the fields of foreign countries. This is what they voted for and they should not be protected from seeing the consequences of their actions.

Mother morning over the body of her killed child.-Bulgaria.

Manik : Tell us about your project ‘Brides For Sale’?

Brides For Sale is a project about a small Tinsmith community in Bulgaria who still follow an old tradition of selling their young daughters to the man who wants to marry them and who is able to pay the highest price. Often the father of the bride asks 15-30,000 Euros depending of the girl’s age and beauty. Virginity also plays an important role in the money exchange. I see as an injustice the fact that 12-13 year-old girls are not allowed to study but have to stay at home and learn how to be good housewives. The project is difficult because the Tinsmiths are closed societies and gaining their trust is hard; especially when I disagree with their practices. The work is going slowly, step by step, I meet new people who allow me into their houses to speak and photograph their young girls. It is one of these projects that what you photographed is never enough, so I see myself working on it for one or two more years. I hope that after it is done and I am able to publish it or exhibit it, it will open a conversation about the rights of the young women and eventually lead to some changes in their society. I hope to raise some money to be able to finish this project. If somebody is passionate about women issues and would like to support the work, please contact me.

An old man in an empty store during the last winter of communist regime in Bulgaria.

Manik : What are your plans for the future?

In February I plan to start working on a new project that involves photography, multimedia, book and a documentary movie with a working title “Warriors from the Reservation”. My partners in the project are photojournalist Anthony Karen and Kris Wetherholt of the International Information Policy Foundation and Media Storm. The project is about the old warrior tradition among Lakotas that sends thousands of Native Americans into the U. S. Army, to defend the country that occupies their land – the United States. How easy is it for them to re-enter their society after returning from conflict? How do they treat their mental traumas in isolated places like the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota?

It is my hope that if our project articulates clearly the issues these Native American soldiers face, it may lead to some changes in the way military treats their warriors in the time of peace; an issue that every democratic society should pay attention to.

A skeleton of a watchtower used in the No Man’s Land of Bulgaria for constant surveillance of the borders during the communist regime. Many people who disagree with the regime lost their lives there- Bulgaria.

Manik : Being a photojournalist yourself, what has been the most interesting story you have done?

It is a very interesting experience to talk with photojournalists whose devotion to photography and social justice light the darkest places in our world. I am completely fascinated to learn, through these interviews for FotoEvidence, how many photographers around the world document injustice without being sent on assignment, without being paid, even supporting the work from their own pockets.

Is this just for the love of photography or each of these people care about human dignity and knows that the camera is a tool that can bring change? I hope their confessions will inspire young photographers who want to walk on their path. I hope that their work will be seen as proof that it’s worth risking your life to inform and make the world a better place. I know all these words sounds over used, even banal, but they are the only words I can use when talking about photojournalists like Gary Knight, Jason Howe, Greg Marinovich, Eros Hoagland, Boniface Mwangi and Zoriah Miller. I want to mention the unstoppable fighters for social justice that are Donna Ferrato, Bharat Choudhary, Brenda Ann Kenneally, Alex Masi, Vlad Sokhin and Claudia Guadarrama; all these interviews can be found on the FotoEvidence web site.

The mayor of Piperitza, small village in the No Man’s Land, shows with pride his portrait as young soldier. During the Cold War, Bulgaria’s southern border with Turkey and Greece separated the Socialism form Capitalism. An electrified, barbed-wire fence created a no man’s land with restricted entry, restricted movement, restricted lives. Only people loyal to the regime were left inside the restricted area -Bulgaria

Manik : You’ve been credited for being a pioneer in digital photo books with the book ‘Bronx Boys’ by Stephen Shames. What is the scope of these books in the future?

To create the book ‘Bronx Boys’ by Stephen Shames we developed unique software to produce a unique digital photo monograph that can be downloaded to your computer and you can own the book forever. Moving pages, hi-resolution photographs and the ability to enlarge each image made the book innovative for the time it was produced, in 2011. The book received broad recognition in the press and was called “one of the first true digital photo monographs” by TIME magazine’s Paul Moakley.

Do I believe in the future of digital photo books? Yes, I do. When ‘Bronx Boys’ was released on the FotoEvidence web site, we had two purchases in the first 30 minutes: one from Hoboken, NJand the second from Omsk, Siberia. Do you think that the photographer who bought the book in Siberia would be able to see Stephen Shames work in his local bookstore? No, he can’t but he got our digital photo book and as a bonus, we put him in touch with Stephen personally, something that could be included in a digital book.

There are many positive aspects of the digital photo book publishing. To create content using multimedia, audio and video imbedded in the book. Low cost of production, low prices accessible to everyone. Work that would never be published as hard cover books because of a content or high cost involved in the printing can be produced as a digital books and reach its audience.

After Bronx Boys we published a few more digital photo books for the Apple iPad – “Black Tsunami: Japan 2011” by James Whitlow Delano, “Before the Limit” by Claudia Guadarrama, “Sicarios: Latin American Assassins” by Javier Arcenillas. We’re working with two photographers now to publish books on both Android and Apple platforms this year.

It is like everything else. Some people like it, some people don’t. But clearly the digital era is here for photo books.

Billboard depicting the Cuban leader Fidel Castro holding a gun. The billboard was erected on Plaza de la Revolution for the military parade that celebrated Castro 80th birthday -Cuba.

Manik : Where do you see FotoEvidence a couple of years from now?

I wish to believe that FotoEvidence will sustain all challenges that come with supporting documentary photography. I hope that our small team will have the strength to continue fighting for justice and support the work of courageous photographers. If we are successful, perhaps FotoEvidence will become the organisation that influences lawmakers and governments in the effort to keep and defend human dignity.

A family mourning for a killed by the Serbian militia man, during a mass burial -Kosovo.

Photography Interviewed By Manik Katyal

Photographs by Svetlana Bachevanova