Germany –

During the Spanish war with Napoleonic France, Francisco Goya made The Disasters of War. In three series of prints he detailed the horrors of the battlefield, the slow suffering of siege and starvation and the re-establishment of a corrupt elite. The pictures were made between 1810-1820, but were not published until 1863, 15 years after Goya had died.

One year earlier, Alexander Gardner had made his ‘Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter’, a picture where the bodies have been rearranged for dramatic effect. The picture was first shown in an art gallery accompanied by the caption

“What visions of loved

Ones far away, may have

Hovered above his stony pillow! What familiar

Voices may he not have

Heard like visions beneath

The roar of battle, as his

Eyes grew heavy in their long, last sleep.”

So self-censorship and sentimentalisation of war for propaganda purposes are nothing new. Nor, if you think of the work of Roger Fenton and many many more, is the omission of death. Even in the 19th century, it was a convention in some places not to show your own dead in photographs of war. Other people’s dead were fine, but your own – no way.

There were times when you could show the dead. In Europe, a mainstay of any ‘oriental’ album of the 19th century was the grisly execution picture, the decapitations, the dismemberments and the thousand cuts. The ‘noble savages’ of photographers such as Edward S.Curtis were almost a counterpoint to this, but far more prevalent was the ‘savage savage’, the Johnny Foreigner who delighted in torture, cruelty and the most painful of punishments, the kind of thing the west still likes to think it did not do then and does not do now. It’s mistaken on both counts.

There are other pictures of death; the pictures of the Holocaust that were shown to local German populations to convince them of the brutality of the Nazi regime. These were pictures as evidence and proof. Or there were trophy pictures that celebrated death; lynchings in the USA that were turned into postcards; black bodies hanging off limbs of trees as crowds of onlookers smile for the camera.

But this depended on the audience. For most Americans, including white Americans, these pictures were an indictment and as attitudes change, they have become pictures of shame, that cast light on the past and also manage to distance it from the present. These are pictures that can help us pretend that everything is better now, that that was then and this and this is now, that blind us to the injustices of the present.

Then there are contemporary pictures as a shaming call for action. At the end of May this year, shocking pictures were circulated of two young Indian girls, Murti and Purba. hanging from a tree. They had allegedly been gang-raped strangled and lynched by a gang of men. Angered by the inactivity of the authorities locals left the bodies hanging to be filmed, photographed and disseminated in the hope that justice would happen. The images were circulated (with varying degrees of censorship), but the justice is still on hold.

So there is lots of death in photography and there are varying levels of censorship. It’s riddled throughout the history of the medium and it’s complex and contradictory and comes with its own regional conventions and codes.

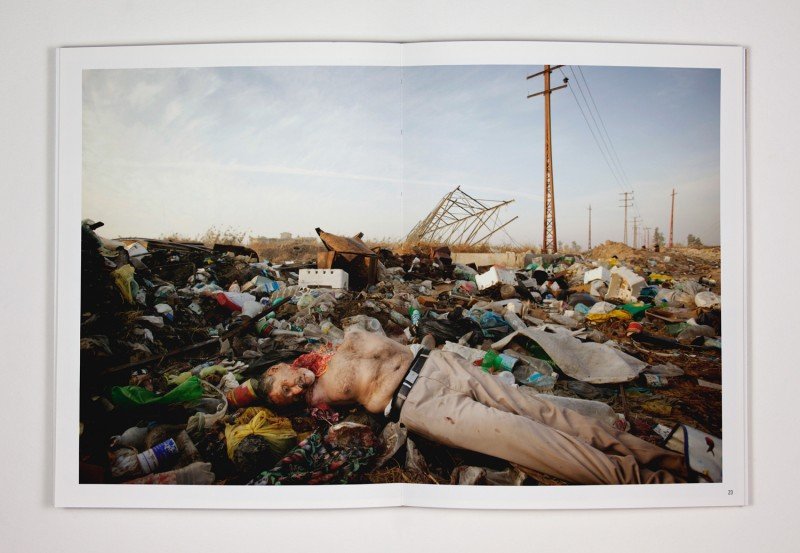

And that’s where Christopher Bangert’s War Porn fits in. It features pictures of death from Bangert’s photographic career, most of which are unpublished; bloated bodies from the Indonesian tsunami, a body of a man found on a Baghdad dump, his neck mauled by wild dogs until the bones show. There are pictures from Iraq, Palestine and Afghanistan, a screenshot of the hanging of Saddam Hussein and the “aftermath” of a lunch between local sunnis and the US ambassador to Iraq.

If you want to see all the images, you have to cut the pages. Or fold them over and peak beneath the crease. It’s a technique that has been used by Melinda Gibson and Ben Krewinkel in their books, a means of getting people to really engage with and focus on the pictures in the book. And of course to do that you have to destroy the book. It’s a design element that questions the value of the book as fetish, but is as cold-blooded a part of that fetishism as the questioning that accompanies it.

So what’s the point of it all? In the introduction, Bangert says that these are his nightmares in print. He writes that they are not his best pictures, that he is ‘…just trying to start a conversation about how we deal with – or don’t deal with images of horrific events. It’s an experiment: what happens if I switch off my self-censorship mechanism off?’

He also writes that it is about remembering and mentions the grandfather who served in the Nazi regime and who ‘chose to forget’. So Bangert’s pictures are pictures that choose to remember, that help us to remember what goes on in the world around us, what we choose to support or oppose, what our names are signed up for.

It’s a selective remembering of course and it applies only to the specific photographic culture of parts of the printed western media. The censorship of death is an inconsistent convention. In parts of the world, there are numerous websites that will show, in the most horrific detail, the victims of shootings, bombings and drone attacks, that commemorate or accuse. They are sites of evidence that are the visual equivalent of a sledgehammer. There really is no arguing with a picture of a baby with its guts hanging out. There used to be sites patronised by the US military that would show those killed by Americans; more trophy sites. And of course, there are the very contemportary jihadist sites that celebrate their bombings, shootings and killings. The visual discourse of death is rich, varied and plentiful.

These sites aren’t in the book and nor are discussions of how, where and why death is shown. So in some ways, Bangert’s book is limited. But then Bangert is not claiming to provide a huge overview of death, war, propaganda and sacrifice. He’s showing his pictures and his experience. He’s showing how he has censored himself. Published by Kehrer Verlag, War Porn is his antidote to that self-censorship. Most of all though, Bangert is starting a conversation. It’s a good start, but what comes next?

Colin Pantall is a UK-based writer, photographer and Senior Lecturer at the University of South Wales, Newport.