Emaho: You’ve described your design trajectory as increasingly focused on interiors and objects after years in architectural practice, noting that “my furniture design began from a desire to work on things in even greater detail.” How did the shift from large-scale architecture to furniture and interior design change the way you think about space and scale?

Bogdan: The shift from architecture to interiors and objects fundamentally changed the way I understand scale, because it forced me to stop thinking of space as an abstract composition and start thinking of it as something deeply physical and intimate. In architecture, you often work with the idea of atmosphere and proportion from a distance; you design frameworks, sequences, volumes. But when you move into furniture and objects, you enter a world where every millimetre matters, where the human body becomes the true measure of design.

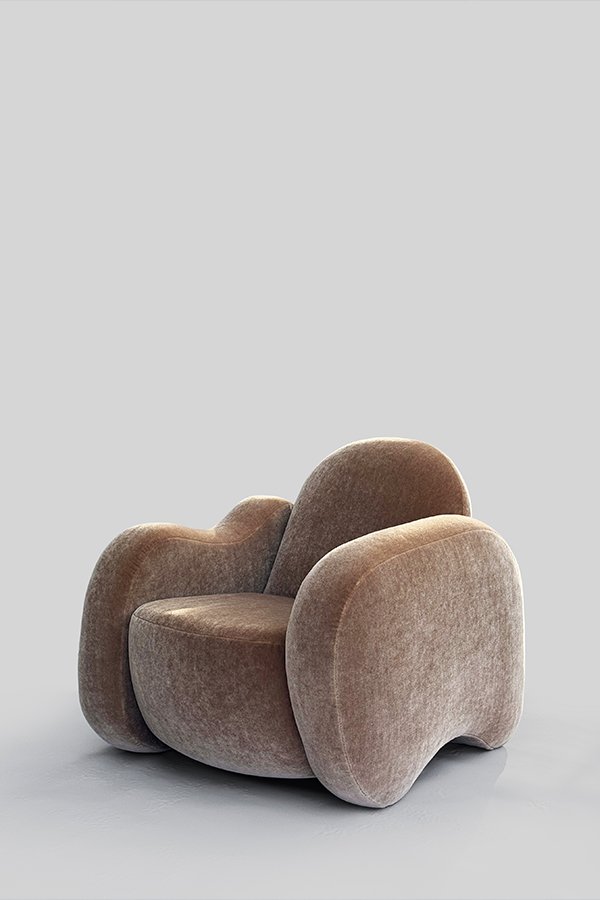

Furniture design came naturally from a desire to go deeper into detail, but it also made me more aware of how space is actually perceived. A chair, a table, or a lamp can completely alter the way a room feels, sometimes more than an architectural intervention. Objects create the emotional temperature of a space. They define intimacy, comfort, tension, softness, or even authority.

This shift also taught me that scale is not only about size; it’s about presence. A small object can carry monumental weight if its proportions are right, if the material is honest, and if the gesture is clear. In many ways, designing objects has made my architecture more disciplined, because it trained me to be precise, to eliminate unnecessary noise, and to edit my thoughts and decisions.

Ultimately, working at a smaller scale has sharpened my understanding of the larger one. It reminded me that architecture is not just structure or volume; it is a collection of decisions that people touch, live with, and feel every day.

Emaho: You work across scales – from interiors to limited-edition design pieces represented by Kolkhoze Gallery, Paris. How do you navigate the transition between object and environment, and what conceptual threads carry across these scales?

Bogdan: For me, the transition between object and environment is not a shift in mindset, but simply a change in resolution. Whether I’m designing an interior or a limited-edition piece, I approach both as part of the same language: an exploration of proportion, atmosphere, materiality, and presence.

An object is never isolated, it always exists within a spatial context, even if that context is only implied. In the same way, an interior is essentially a composition of objects, textures, and tactile moments that shape how the space is inhabited. So, the relationship between the two feels very fluid to me. I see furniture as architecture at a human scale, and interiors as an expanded landscape of objects.

The conceptual thread that carries across these scales is restraint combined with expressiveness. I’m drawn to structured minimalism: clear geometry, calm compositions, but always with a precise gesture that introduces character or emotion. That gesture might be a material contrast, a curve, an unexpected colour, or a slightly surreal proportion.

Ultimately, I’m interested in creating pieces and spaces that feel timeless but not neutral; environments and objects that remain quiet enough to endure, yet distinctive enough to be remembered.

Emaho: When discussing form and function, you’ve noted that “form follows function… but it depends on the context and at what scale.” How does that belief shape your approach when designing bespoke pieces that are simultaneously functional and sculptural?

Bogdan: I believe form follows function, but not in a rigid modernist sense. For me, it’s always contextual. Function is not only about practical use, but also about psychological use. A sculptural piece can be functional if its role is to hold presence, to anchor a space, to create atmosphere, or to shape how someone moves through a room.

When designing bespoke pieces, I begin with the functional necessity, but I treat it as a starting point rather than a limitation. The function establishes the rules, the scale, the ergonomics, the stability. But within those boundaries, form becomes a way of creating meaning. It becomes a narrative gesture.

I’m interested in objects that feel almost architectural, pieces that carry weight, clarity, and a certain discipline; but that also introduce emotion through proportion or material. In that sense, sculptural form is not decoration; it is an extension of purpose. It’s what transforms an object from something useful into something lasting.

Emaho: Your collaboration with Atelier Kairos on hand-knotted carpets like Étude no. 3 and Motif no. 1 foregrounds the handmade and the sketch as part of the work’s presence, where you said the creative process became part of the piece itself. How do you see imperfection and trace as strengths in design?

Bogdan: I’ve always been drawn to the idea that imperfection is not a flaw, but a trace of life. In handmade work, the irregularity becomes proof of presence, and it reminds you that something was made by a human hand, not generated by a machine. That human trace gives an object warmth, vulnerability, and authenticity.

Working with Atelier Kairos made this very clear, because the carpets carry the memory of the process inside them. The sketch is not erased, it becomes embedded. The gesture remains visible. And that visibility is powerful, because it transforms the piece into something more than a finished product; it becomes a record of making.

I think in contemporary design we often chase perfection as a kind of aesthetic control, but true permanence comes from honesty. A piece that reveals its process feels more alive, more intimate, and more emotionally resonant. Imperfection introduces softness into discipline, and that balance is something I value deeply.

Emaho: Projects such as The Edit Showroom and the Maria Lucia Hohan flagship in Bucharest demonstrate a choreography of space where narrative and sensation play key roles. How do you translate ideas from theatre, cinema, and scenography into interior architecture that invites experience rather than mere observation?

Bogdan: Theatre, cinema, and scenography have always influenced how I think about interiors because they are fundamentally about experience. They teach you that space is not static, it is something that unfolds in time. It’s about choreography, framing, tension, and release.

When designing interiors like The Edit Showroom or Maria Lucia Hohan, I think in sequences rather than rooms. I imagine how someone enters, what they see first, how light guides them, where the pause happens, where the surprise happens. It becomes a kind of narrative composition, where materials and proportions act like scenography tools.

I’m also interested in atmosphere, the emotional layer of a space. Cinema, in particular, is deeply influential because it teaches you how light, shadow, and texture can completely transform perception. You can make a space feel intimate, monumental, theatrical, or serene without changing its actual size.

Ultimately, I want interiors to feel inhabited by a story. Not a literal story, but an emotional one, a sense that something is unfolding, that the space invites participation rather than observation.

Emaho: You have talked about building strong relationships with clients based on dialogue: “I think the most important thing is the person who will use the space… after that comes the creative process.” How does this client centred approach influence the aesthetics and logic of your work?

Bogdan: A client-centred approach shapes everything, because it reminds me that architecture is not an aesthetic exercise, it’s a framework for someone’s life. The most important part of any project is understanding who will inhabit it, what they need emotionally, and how they want to feel inside the space.

This doesn’t mean that the client dictates the design, but rather that the design becomes a dialogue. Through conversation, you start to understand their rhythm, their values, their contradictions. And those nuances influence the logic of the space: how open it should be, where intimacy is needed, how much restraint versus expression feels right.

I also believe that a space should never feel fully complete. It should feel like it leaves room for the person to unfold within it. My role is to create an architectural structure that feels coherent and intentional, but still open enough to absorb life, objects, memories, and evolution.

Emaho: Your design of retail environments like Lunet Pop-Up and The Edit Pop-Up shows flexibility in spatial logic and display strategy. How do you conceive retail as a realm for architectural storytelling rather than a purely commercial backdrop?

Bogdan: I see retail as one of the most exciting typologies because it allows architecture to become narrative. A retail space is never just a container for products; it’s a stage for identity. It’s where atmosphere becomes strategy, and where emotion can become part of the experience.

In projects like Lunet Pop-Up or The Edit Pop-Up, I approached the space as a temporary world, almost like a set design. The goal was to create a spatial story that communicates the brand’s values without relying on obvious branding. Display becomes choreography, and circulation becomes part of the script.

I’m interested in the idea that people don’t remember products as much as they remember how a space made them feel. If the architecture creates curiosity, intimacy, or surprise, then the retail environment becomes something memorable and cultural, rather than purely commercial. For me, retail design is about creating a moment, a temporary experience that stays in someone’s memory long after they leave.

Emaho: Recent expansions of your practice include collectible objects and furniture in limited editions. How does the discipline of designing for permanence – objects intended to be heirloom or collectible – reshape your view of sustainability, craft, and cultural legacy?

Bogdan: Designing objects meant to endure, pieces that are collectible, heirloom, or culturally valuable, inevitably changes the way you think about sustainability. It shifts the conversation away from trends and toward permanence. The most sustainable object is one that will never be thrown away.

When I design limited-edition pieces, I think about longevity not only in material terms, but in conceptual terms. Will this object still feel relevant in 30 years? Will it still hold presence? Will it still deserve space? That kind of responsibility forces discipline.

It also deepens my relationship with craft. Working with ateliers means respecting the pace of making, the intelligence of the hand, and the reality of material. It becomes a form of slow design, where every detail is intentional and every gesture carries meaning.

In terms of cultural legacy, I think collectible design sits in an interesting territory between art and utility. These pieces can outlive their immediate context and become part of a broader cultural narrative. That possibility is inspiring but also humbling. It reminds me that design is not only about aesthetics, but also about creating objects that carry time with dignity.

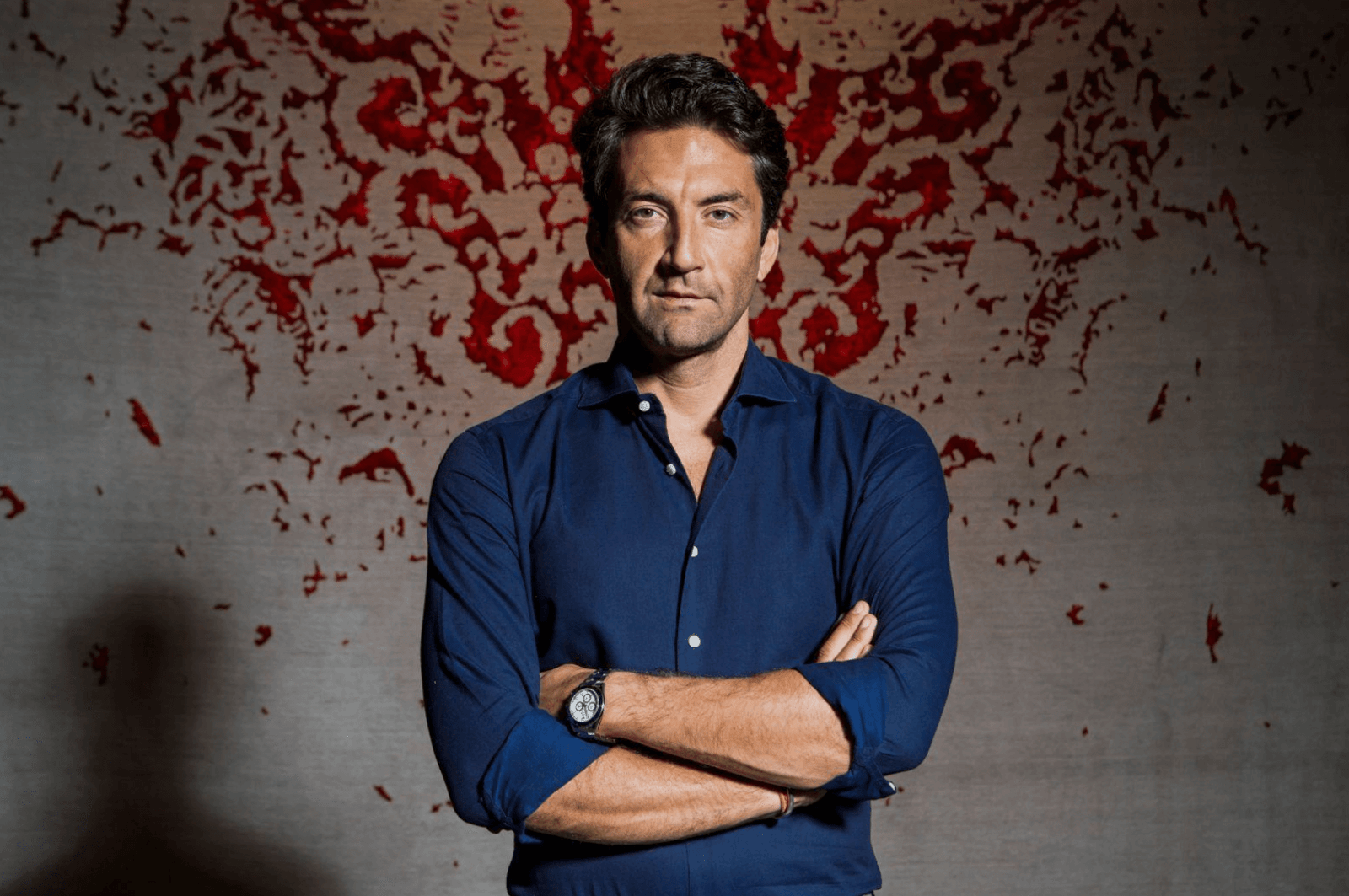

Bogdan Ciocodeica Website