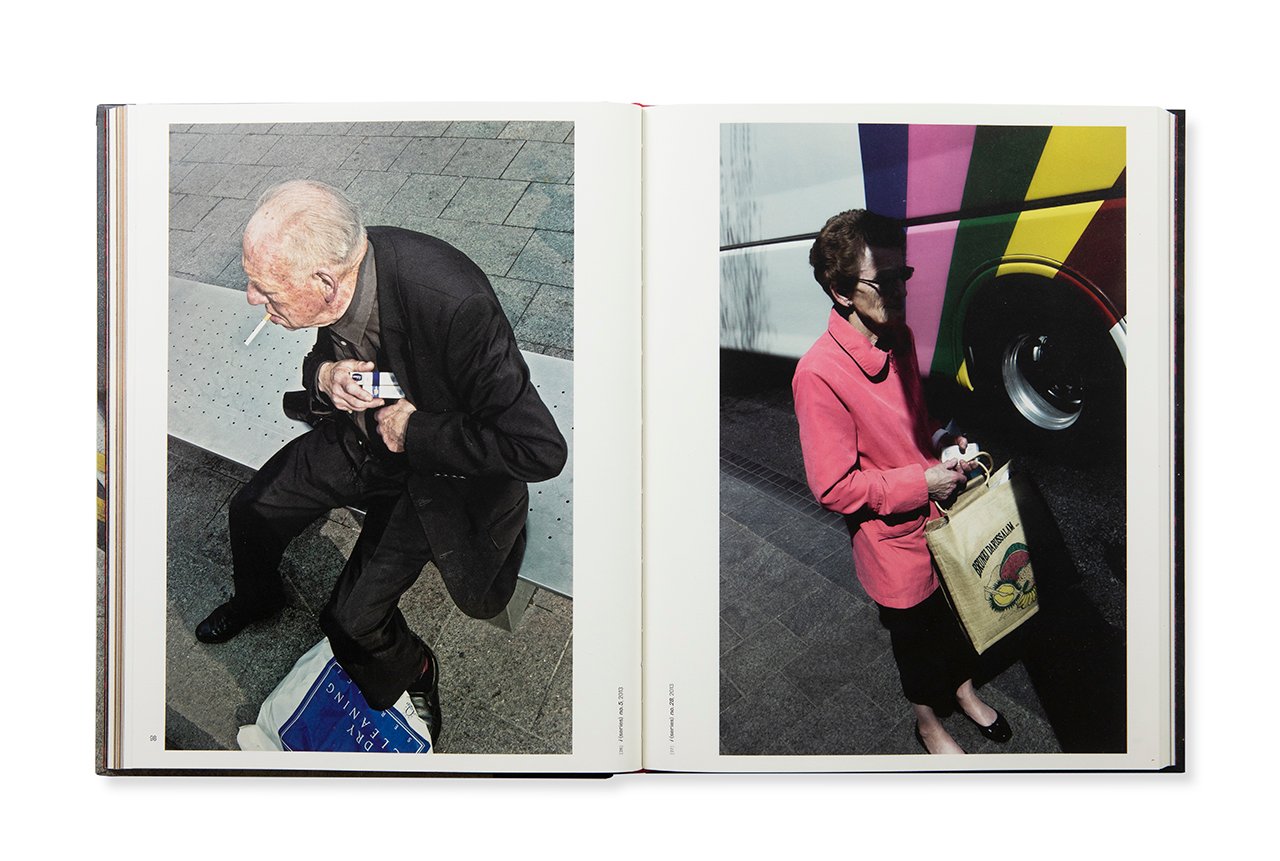

USA –

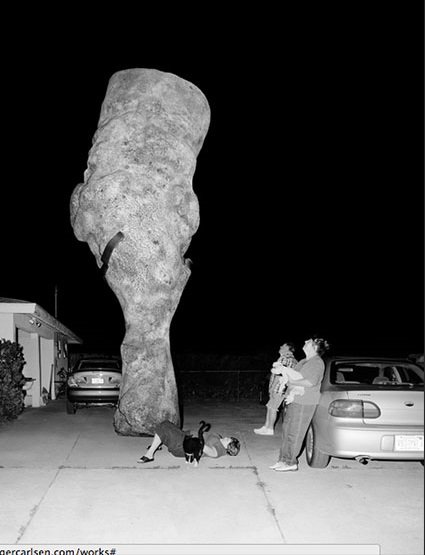

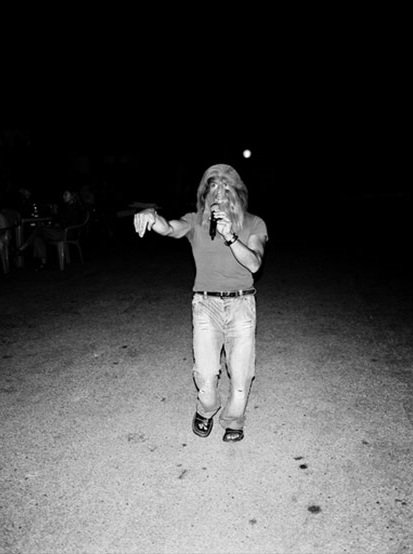

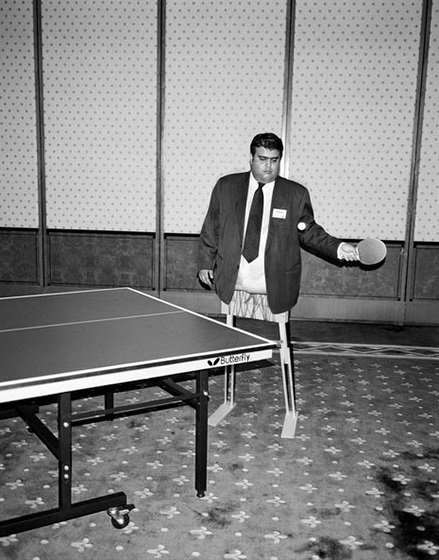

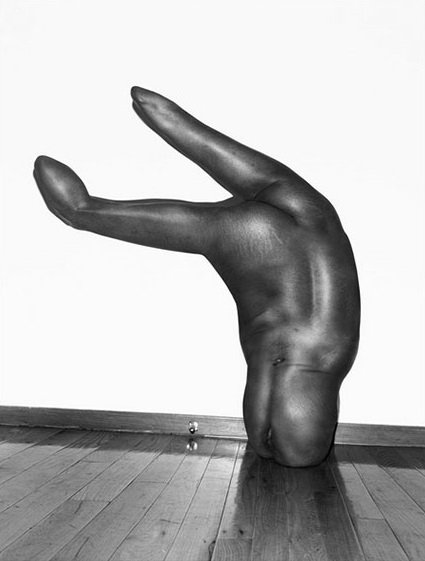

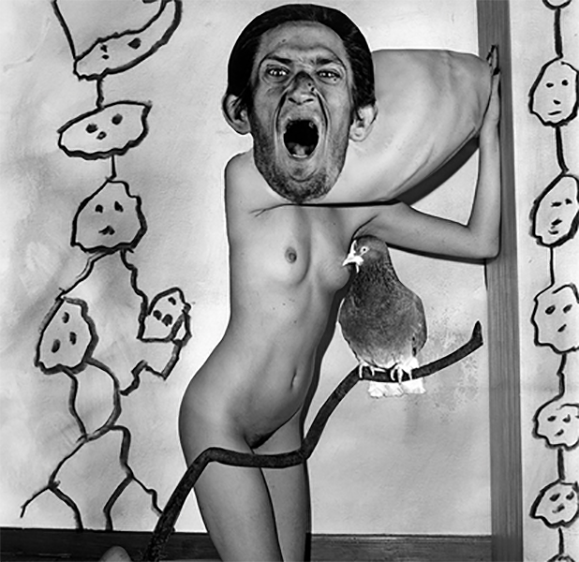

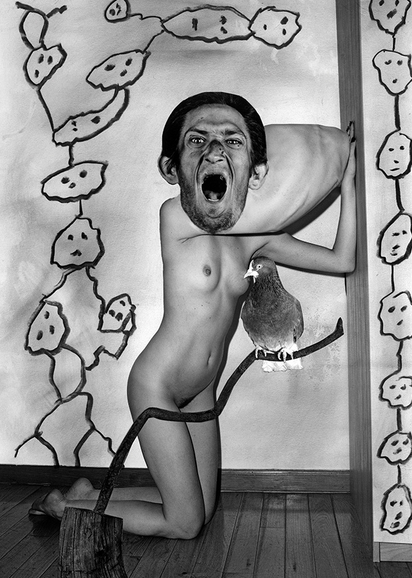

Asger Carlsen’s images consist of mutilated, disfigured and distorted human forms with a typical obscure quality to them. He has collaborated with photographers like Roger Ballen and media entities like Esquire and New York Times. Carlsen has also authored and co-authored books based on his work. Presently he lives and works from his studio in Chinatown in the New York City.

What is the inspiration behind your human-sculptural photography? In one of your interviews you’ve mentioned that “style” is very important and also that you were inspired by Andreas Gursky, a German landscape photographer, at the beginning of your career.

Gursky was a long time back thing. I believe I said it in relation to explaining where I came from and what I used to do.

It’s been a long creative journey for me. I came from a professional photography world as you know. In the beginning as a photojournalist and later on as an ad photographer, photography did not fulfill my creative desire and it did not seem to be creative enough, and that’s how I started doing this work.

When did you decide the move to NYC? How has the transition been?

I have always been very well received in America. I have nothing bad to say. It’s always been a pleasant, welcoming feeling. When I was working in Europe, I was already listed as a photographer with many years of working experience in photography and in the industry. I came here because a commercial agent contacted me. I signed up for him and started working here. I got more and more work and that led me to moving here, eventually. I only work with galleries now. I don’t have a commercial agent anymore.

What kind of commercial work did you do in New York when you arrived here?

At the time, I was aiming to make it as a commercial photographer. I did a lot of stuff for American Luggage and for publications like Wired and Esquire. I also did some random commercial jobs, for like, Bank of America, Levis, and stuffs alike.

In one of the interviews you said, “I am tired of photography”. Please comment considering that you are using photography as your primary medium to create something so unique, which is very interesting.

It sounds reasonable. The work that you are referring to, now, is not really a photographic work. The first body of work that would fit in this style was entirely based on untitled images, and then the second major project, the Hester was also started at a point with the untitled images. Then it turned into very short basic photo sessions where I’d shoot models. But you know, I wouldn’t really care about capturing these images, I was basically having the model posed in different ways, that’s why I refer to this process as collecting material as opposed to shooting pictures. Obviously, collecting material for future use.

You have also mentioned that a project that would take several minutes to shoot could take years to reach its final state. You use Photoshop to achieve the desired effect in your images. The entire process must be very painstaking. Could you demystify the stages in this process?

Going back to what I just said before. The photo sessions are not really that important to me. I could have someone else shoot these images for me, I wouldn’t care. But you know basically it’s a model that I caste somewhere and then I would have that model pose for me and that would not take may be more than 20 minutes. So even though I shot something 5-6 years ago, I can still utilize it, I can still use those photographs to compose what I want to do. The idea that you have to travel somewhere and you have to find your subject and engage with your subject, that was fine, I mean I had many good experiences doing that but it just didn’t seem to me creativite enough. I couldn’t just wake up and just become creative. That’s why this way of working now seems more appealing to me because I just get up and just start working. It’s more of a studio-based process as opposed to external.

In the past you have also quoted that “I perceive photography as more of an object” and you’ve also called yourself more of a “material director” than a photographer. Would you elucidate on that?

I really said that! I don’t see myself as a director. I don’t see myself as photographer. I am just seeing myself as someone who has skills and is using photography. When it comes to the actual idea of being a photographer and a physical image, I would say my images are not good images, they are not good pictures. They are not amazing photographs in that sense. I would say, I am more of a sculptor now. I do have certain photographic obligations or concerns in terms of quality that I print or other technical stuff with the prints that I need to pay attention to. It was not a process of sitting around and say oh do I like this image or another image. It’s about do I like this form or do I like this shape that I am building. All these things are constructed in person.

In “Place of the Inside out”, where you collaborate with Roger Ballen, you’ve combined your art form with the visceral and dark elements that Ballen’s known for. The images have a deep surrealistic tone. How was the experience collaborating with Ballen?

A collaboration is always kind of a compromise, I would say. But you have to do something because the other person cannot proceed without your work too. So, it’s no longer just you. But basically, the way it has been happening is either I would make an image or I would create an image and send it to Roger and he would do his part of the work. And sometimes, he would send fax and I would change it a little bit and sometime I wouldn’t change and that is how it happens here. We have met a couple of times now, physically, but usually we would come to a decision over Skype or phone, part of which is continuing and testing with new ideas.

A lot of things came out of it. We are in a process of finalizing a complete body of works after we did the collaboration. We got a good response and we got a couple of book offers from publishers and they were ready to publish our book, so that led to continuing the collaboration. At this point, we are pretty much wrapping up the last couple of images for a book.

If you look at the images we did for Vice, it’s going to be an extension of that. I work on computer. He works with proper print.

We still have a lot of things in common in terms of our ideas. The work we are doing comes from a very sort of internal place. I think he calls his photography as mind-soul photography. To which I can relate.

In one of the interviews, you said, “I have no desire to photograph naked girls”. But yet, your last book ‘Hester‘ is all about female nudity.

I said this because someone asked that what are you trying to say, is it a comment on women or on their sexually. It’s not. I wanted to make something that wasn’t referring to a specific time. I wanted to have it feel like it was timeless.

I could go ahead and shoot men but on a more technical aspect, it’s difficult to shoot men because they have more body hair. So that I didn’t wanted to do.

While working as a crime scene photographer, why did you shoot all images in black and white?

Early 90’s, the color photograph was not easily available. So, everything was black and white. Of course, I have a long history with the printing black and white in a dark room. Having said that, I also did a lot of coloured photography when it became entirely digital and something that you could do easily. I wanted it to be a sort of in sync with the history of photography and the idea that we automatically believe that a black and white image is an original image, like it is a true image, maybe communicating a story or communicating a real event in case of a news story. I found that interesting, to use the history that black and white has, and something that’s documenting a real event. These extreme projections of reality and extractions that I came out with seemed like a good way to tone down these extreme stories that were coming out of these images.

From being a crime scene photographer in which one has to follow a stringent policy of showing “as is”. Where any alteration to the image is considered to be a taboo, you took to distorting and disfiguring human form in your images. How would you describe this transition?

Back in those days, in the 90s, there was already a long debate going on for years, what you could do to the image and especially when the Photoshop came, which was around I think 1996-1997, you know at that time we started having computers and started scanning. We could remove dust with this tool in the Photoshop that’s called the span tool. Before, you were removing dust with sort of air or maybe afterward you would retouch with a pen. So, you started scanning there was a lot of dust, you have to get rid of it. There was a huge debate, now you are changing the image because you are replacing pixels with other pixels and that’s altering the image. People were saying that you can’t do that and then later it was said that you can do that but what can you continue doing with the photographs, can you consolidate two of them into one photograph? It was all this fear and it is still going on. Then what happened that people started using photograph and it would make the picture better and then they may be would add an unnatural contrast to the image and that became an issue. That’s changing the mood, you know, making it more dramatic. That’s not ok.

I mean, I can see your responsibility as a media person you have the responsibility to portray the real event as it’s happening. You can’t lie. But between that and other work, there’s a long tier of ad work, where you are certainly allowed to do that. So, it was no longer so much of a concern for me. I did not have those responsibilities anymore. Last year, I did a lecture for the school of journalism in Denmark where I talked about it, I mean they can disagree. In their world, it’s really not ok to do that now. I couldn’t care less now.

Your images as they are made of flesh and bones and are known for their uncanny, grotesque and phantasmic quality. They have been called “gruesome” as by removing the face from the images and oddly mutilating the bodies, it gets hard to empathize with the figure. To that effect, what is that you want to evoke in your audience when they come to see your exhibit?

I am not necessarily thinking about what people should think about my images. I just make the images that I want to make. On a personal level, if you are asking me if I like the images always or think that they are gory or go over the board sometimes. I do think that they do go overboard sometimes. That’s something I’ve questioned myself: is this really something that I want to do, is this ok? For me, the evolution of doing this, is always much more important than that question.

If I create these situations and scenarios in the images that have developed an idea for an understanding of what that is, for me that is more important. That always wins. It’s the journey that justifies for me.

I only make the images for my own self and not for anyone else.

How would you describe your aesthetic sensibility? The surrealist movement inspires you.

I use the techniques of modern days. Not to say, I am not a teenager but I still belong to that younger generation where you use the techniques available. I do like Surrealistic movement and some of the work that they have done. Of course, they had political reasons to do it that I don’t have.

Tell us about some of your upcoming projects.

Sure. I told you about the Roger project that is already in the last stage of being finalized. That’s coming up and then there’ll be something called Paris Photo, a nature photography event in Paris.

I am working on a bunch of drawings. I am also working on sculptures. I’ve started building sculptures, which I do both analog and I also do it on computer.

All the Images©Asger Carlsen

Interviewed by Manmeet Sahni & Manik Katyal