England –

London-based Canadian artist Andrew Salgado has long been trademarked as a painter who only paints portraits of men representing psychological struggle. But it seems with time he is trying to move on from the hate crime he was subject to in 2008 along with his gay partner. Andrew’s emotive, large-scale and gestural oil paintings and visceral, sexually charged videos are an intense exploration of the body, identity, and sexuality. He opens up to Emaho about those subjects as well as his ideas of transgressive beauty and how he paints them on canvas.

Emaho : The men in your paintings are full of pain and anguish. You have also faced tough times earlier by virtue of being gay. Are these correlated?

I think that it’s quite easy to say that these are related, and certainly the 2008 incident was a catalyst for what I view as the political perspective inherent in my work; however, I think it would be misinformed to say it is the inspiration behind my painting. In many respects I have been trying to move away from this as being the focus of my work, as it certainly does not occupy a primary aspect of my life, and I only believe in painting about what is of immediate importance to me.

Parantheses

Emaho : Is there no hidden activism then, where you aim to make a difference through your paintings?

I guess that the paintings are still tangentially related to this aspect. That part of my past helped form me as a person, but the work is no longer linked to this as aggressively as it may once have been. I believe the paintings maintain an element of activism in the sense that I have something to say through the act of painting, and I want to draw attention to issues that perhaps we take for granted. My practice has never been about being decorative; I also believe that it is important to grow not only as a person but also as an artist. Perhaps I am at a crux point, in which I am moving on to talk about new things that are of importance to me.

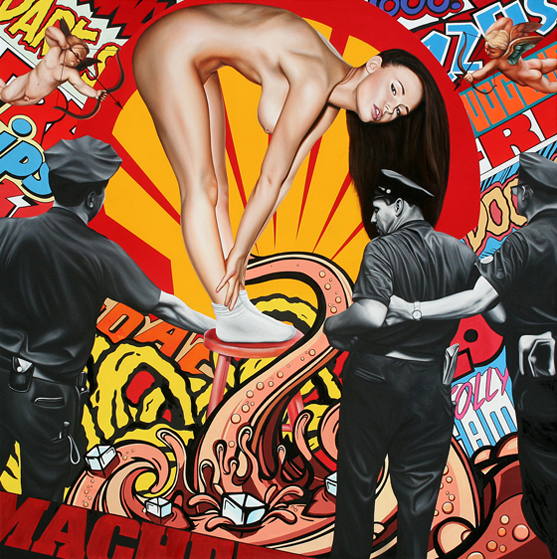

Emaho : Your paintings are about ‘destruction and reconstruction of identity’. Is it exclusively about exploring masculinity or is your work directed towards women also?

Perhaps as a younger painter I was interested in exploring only the ideas as they pertained to masculinity. As a person I think I was also exploring who I was. I’m only 30 now but I feel that I have a little bit of perspective on some issues that I was so concerned about previously. I have begun – slowly – to reintroduce the female form into my practice but it’s tricky because I’m trying to find out exactly what it is I’m trying to say through the use of females. I’ve become so invested in the masculine form over the past years that it’s tricky to introduce a new element. However, I also think it is important to prove to yourself as a painter that you can still take risks that seem completely out of your own comfort zone. I’m interested in how ‘the female’ can be introduced and thereby relate in a truly pertinent way to my practice. Perhaps I am becoming slightly less political in this regard, or I am yet to locate precisely what I’m trying to say as I begin a new series of works.

Patience

Emaho : You say you paint faces because they attract you and you see a story behind them. But while painting them you almost make the lines disappear and abstract the face. Are you trying to blur the stories these faces tell?

I introduce abstraction because I think without it the paintings are portraiture (which I view as uni-dimensional). I’m not interested in accuracy when I paint; I’m interested in exploring the concept behind identity and also the purely abstract properties of paint. I really do see myself as an abstract painter… This pursuit can of course be pushed and further explored, and that keeps me quite interested in the studio.

Emaho : You’ve delved into symbolism saying you correlate paint as a substance with the nature of your subject. Is it the texture, color or its liquid form that makes you feel that way?

The very act of painting is so personal and organic, that I think every move with the brush is related to the immediacy of one’s emotional and physical state at the time of its execution. I guess in that sense the works are all self-portraits, even if the subject matter is of someone else, as it typically is. I think the texture and color of paint is immediate. When I broke my arm last year I was unable to paint for 3 months and someone suggested that I get an assistant to do the mixing of paint while I direct him before making the (more limited) strokes. I thought this was silly because as a painter everything to me is very immediate and unplanned.

Emaho : You have contributed a chapter to The Sexualized Masculine Body published by the Art Institute of Chicago Press. It quotes you as saying that you’re trying to portray the “beautiful monstrosity of masculinity”. Beauty and monstrosity are paradoxical – an oxymoron of sorts. How do you see masculinity as monstrous, yet beautiful?

I’m really interested in ideas of transgressive beauty…I’ve always loved the writings of Bataille and the concept stems from the notion that – as humans – we are simultaneously learned but also we are primarily animalistic. We have base urges that often at odds with the greater conservativism of society. I don’t really think beauty and monstrosity are paradoxical. I think of the figures of Michelangelo or the decadent notion of humanity where physicality is reduced to sex and violence. These darker aspects of who we are as humans and the fine line between polarities has always been quite interesting to me. Of course as a gay man (and further, as one who has been a victim of hate-crime) the idea that my sexuality can be perceived as so deviant by another person as to cause him to inflict violence upon me is, I guess at some level, incredibly fascinating – for lack of a better word.

Playtime

Emaho : In the same paper you have spoken of two artists – “While Barney and Nauman celebrate the nude – in homoerotic and heteronormative erotic capacities – neither is recognized as a queer artist: both are white, heterosexual, overtly masculine (on the surface) and ostensibly all- American”. Do you see the ‘other-ing’ of certain artists within the realms of gay art?

Yes. In the paper I question why ‘gay art’ is marginalized as such. Why are Barney and Nauman celebrated for being so clever and exploratory, while any other artist is marginalized because of his sexuality? The first thing we hear about when we talk about Felix Gonzalez-Torres is that he’s gay. Why should that matter? Isn’t his work about the same aspects of humanity regardless of his sexuality? Doesn’t his work strike the same chord regardless of whether his late partner was male or female? Terence Koh and his works are always viewed so horrifically…so deviantly. I find Barney interesting because his work is so very gay but he’s never really criticized or viewed as such – at least not to my knowledge. In the same paper I also discuss how Carolee Schneemann has done certain pieces that are extremely similar to the works of Barney yet she was criticized vehemently for her feminism and her overt sexuality! Her work was seen through a negative lens but Barney and Nauman’s works are lauded for being groundbreaking. Why should sexual oppression be limited to the confines of the marginalized? Why are gays and blacks and feminists simply lumped together as ‘Othered’ but straight white male art is considered under a different context? Was Robert Morris gay? His work comes across as very gay to me but I think he was straight as well. It’s a double standard that says more about the contemporary status of sexuality in a field that is so much larger than art-history.

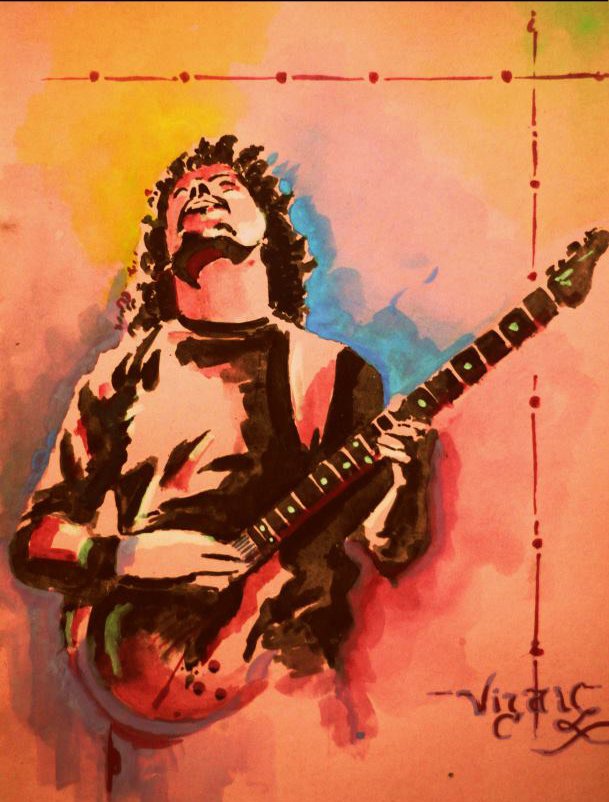

Emaho : What do you have to say about your use of colors? In otherwise grim portraits, there are strokes and splashes of bright colors. Do they depict anything in particular?

I think there can be beauty in handling form and content in a manner where they are at odds. That is to say, a painting with severe subject matter does not also have to appear severe.

Understudy

Emaho : Can you tell us how the artists Daniel Richter & Bjarne Melgaard inspire you? What aspects of their (or other’s) work do you look up to or aim to incorporate in your creations?

Both Richter and Melgaard triumph the absolute deviation from convention in art. Any time I feel stuck I open my Richter book and remind myself that there are no rules to painting. I think a lot of people will find that hard to notice given that I’ve limited myself somewhat – in the past few years – to a relatively frontal, upper-torso framing of the male face. However, by restricting my content I have been able to develop myself as a painter – at least, this is my perspective. I’ve seen subtle but exponential growth in my own ability over the past few years. So I think it’s important for artists to look at others’ work and learn from them. There have been a handful of exhibitions over the past few years that have not only made me rethink how I view that particular artist’s work, but caused me to rethink painting altogether. Peter Doig’s retrospective in 2008 at the Tate Britain was one such exhibition. The deepest influence I’ve ever experienced was in 2009 though, also at the Tate – the Bacon retrospective. I always say that anyone who doesn’t like Bacon is either lying or stupid (laughs).

Emaho : A question about your recent showcase “The Smallest Heart’s Desire” – the heart in the title you say is yours and it was a self-exploratory experience for you. Is it the same with every project you work on?

No. My work is becoming less autobiographical but I suppose “The Smallest Heart’s Desire” was a departure because I had some very personal issues that I was working through at the time that I was unprepared to discuss in any way apart from painting about them. I suppose if I had the words to articulate my life I wouldn’t paint about it, but I still feel that I am using other stories as conduits through which to express my own concerns…and this is what the show was about. It was quite at odds with my previous show “The Misanthrope” at Beers.Lambert, which was quite pointedly about the stories of others. After a while, however, I lose interest in looking at myself and I suppose my viewer does too, so I find it important to cast the net far and wide even if deep down somewhere I’m really just finding new ways to explore my own concerns.

Trust

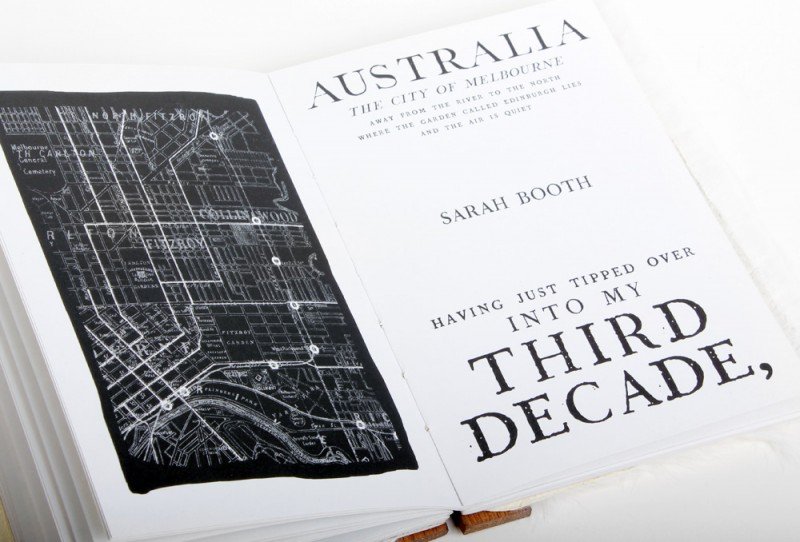

Emaho : Andrew, you’ve been living and working in London since 2008. Do you see any difference in the art scene in London and Canada? Which place do you see as more inviting when it comes to your art and concepts? (Andrew sourced this answer from one of his previous interviews on Antidotemag)

Well, to be totally frank, I don’t see much crossover. I find that any art scene changes quite dramatically depending on the city. After my degree I lived for a year in Berlin – an amazing and alternative experience – with an art scene quite different from what is happening in London, but even London is going through a cultural revolution at present, so I’m lucky to be geographically situated between areas like Berlin or London that are porous cultural sites. London in particular has a thriving art scene with openings, events, and great shows popping up regularly. It’s a spellbinding, fascinating, non-stop city – so I feel that I am still constantly learning; but learning as a practicing artist is an entirely different world than learning as an art student. I was taken aback upon first arriving in London at the sheer lack of direction we were given as Masters students. In fact, I very nearly dropped out of my Masters program 3-months in – I was so disillusioned by it all. After a certain period of time, however, I learned how to see what I first perceived as faults in the UK scholastic system as its fortes. I’m still not sure if that was just making lemonade out of lemons, or if it was a real revelation. Either way, I’m totally contented about having stayed in the program: it has led me to where I am today, and I’m here to stay.

Emaho : Cannot let you go without asking you about your first institutional show in your home country at the Art Gallery of Regina this fall. How does that feel? What are your expectations?

This show is incredibly important for me because it is a homecoming of sorts. I’ve never had a noteworthy exhibition in my hometown (Canada) so it’s an opportunity for me to make a statement and deliver something really important. Of course, I have high expectations for myself, but I always do. However there is a marked personal commitment to this exhibition.

The Artist

Emaho : Finally, is art an ‘act’ or a ‘medium’ for you?