Albania –

Albanian documentary photographer Jutta Benzenberg’s photographs tell the story of her country and its people through three books she has published on the conditions in Albania since the 1990s. Emaho talks to Jutta Benzenberg about her childhood aspirations, her family, her work and her country.

You’ve been exposed to photography from a very young age. What role did your father play in cultivating this passion?

Well, it’s true my father was a photographer but mostly for weddings and events. One day when I was 18 he gave me his camera and said “Come on, take it. Go and take” It was a Yashica. So I took his camera, went to my roof and for three days, I only took pictures. I did still life, self portraits and some other artistic work. So when I showed my father the pictures, he said to me, “I think you have some talent!” (Laughs) Of course I was very proud because my father told me this, and I said, “If you say this, I will continue!” But then, when I really wanted to do photography three years later, he was afraid of how I would make an earning. Parents are okay with us doing such things for a hobby, but doing it for life makes them apprehensive. But I have a little bit of a strong character and I insisted on doing it.

You’ve captured the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of communism in Albania. Your work could one day be historical treasure!

Well, it’s nice that you say this because the Albanians always tell me “I don’t see this” or “Jutta stay in Albania and you will make history”. I’ve been photographing this country for 20 years now and it is a good feeling when they say this, but on the other side I don’t see it. I’m living in the now and not thinking about the past. I haven’t taken the photo for a reason of history. I have done it for me. Not because the country is like this. When I take a picture, I am shooting for myself. Even when I shoot other countries, I look for something that touches my emotions, my inner being. So this is the result of my personality. The present that I’m living in is what matters.

From ‘National Opera and Ballet Tirana’

Over two decades you’ve used both film and digital formats. Which of the two do you prefer?

Well I was forced to shift to the digital camera because in 2007 my house in Albania burnt down. All my negatives and my Leica and my lenses were destroyed. After this happened I had no idea what to do. And then a friend of mine said don’t go back to film; please try digital cameras. Also I had an urgent assignment at hand. When you are working for advertising or design they need the pictures the next day, so I had to move fast. I was hesitant to move over to digital, I was not happy at all. I really had to learn with the camera and its properties because I was used to film and black and white! So now I had these colour pictures in front of me and I was not very satisfied. But after I got the Canon 5D, I felt much better like I had with the Leica. And I was back at photography. I’m not using a lot of Photoshop and when I do, I pretty much only make changes that I would before – brightness, contrast and that’s about all. My photography is kind of old-school.

Which is your favourite photograph?

I cannot say that because that choice is always changing. I am changing as a person constantly and so is my favourite photo. I also cannot say because when I see my photograph on my camera, I often see it as another person. From the moment that I took the photograph, I have changed. I am more than one Jutta.

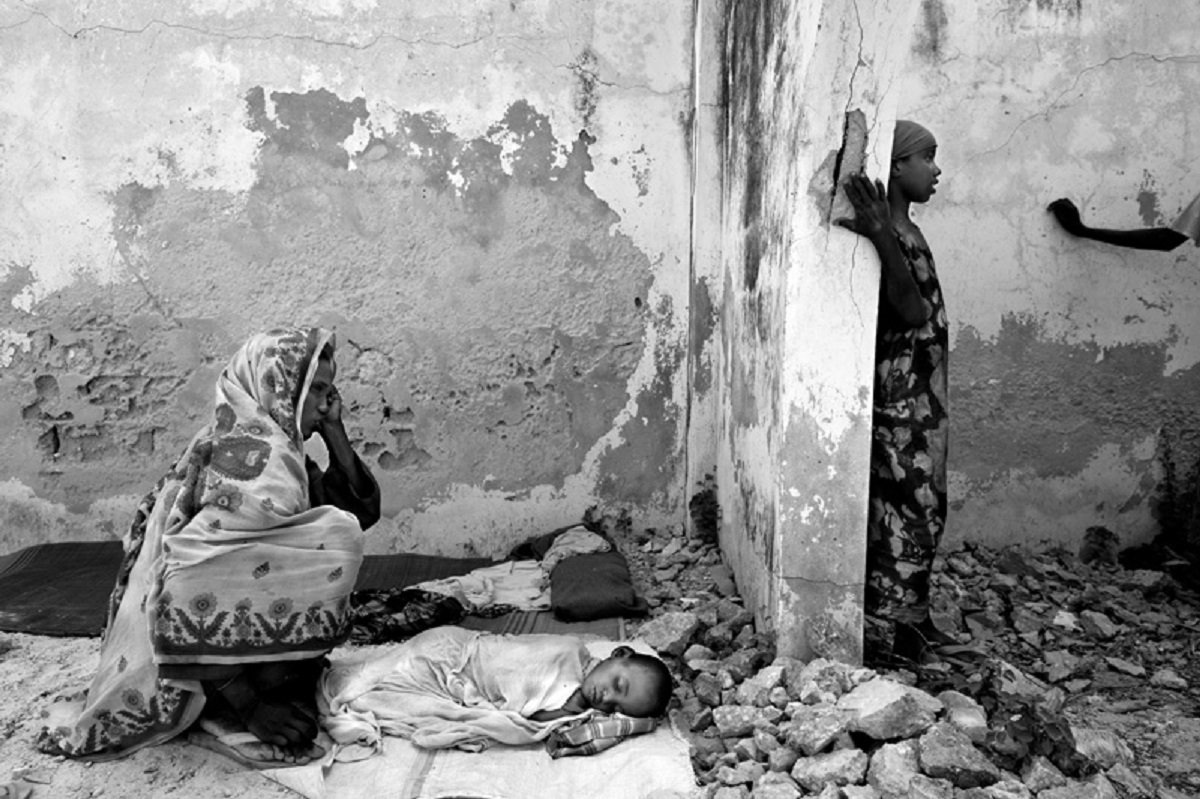

From ‘Bodies of Water’

A number of photographers choose to use monochrome when documenting conflict. Are you one of them?

Now, I always take my pictures in colour and then I try how it looks in both colour and black and white. Some pictures cannot work in black and white; others only work in black and white. I am not fixated on any one subject as a “black and white” subject. Earlier there was only black and white film but now you have so many possibilities. We’re spoilt for choices.

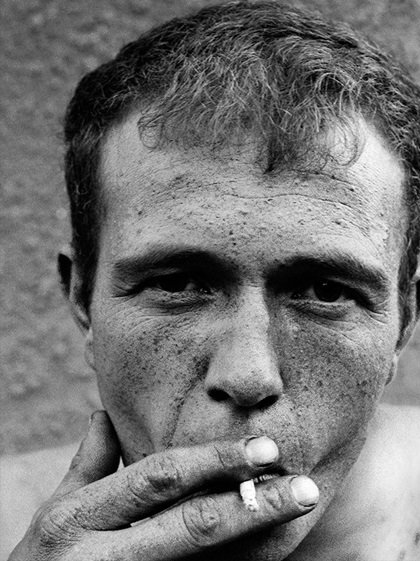

From ‘Phoenix’

How has your perception of Albania, and Tirana in particular, changed between the publishing of your three brilliant books?

Of course, Tirana changed a lot in the last 20 years but when I go to other regions like North Albania, even in villages near Tirana, I see there’s not much change. Especially in North Albania, when I went to the mountains, I lived for two days with a family and it was the same house, the same property and I felt the same feeling I had when I went there 20 years ago and had done the same thing. So, very little seems to have changed in Albania.

Do you see the political situation getting better? Do you think there’s a change in the subject of your photos over a period of time?

Oh I’m not a political person. And really, I don’t know if it’s getting better. Sometimes I think it is, sometimes I think it’s not. But yes foreigners, when they come here they say things are getting better. There are so many problems and I think of why it is not changing. I wonder why there is such difficulty and why the government is still unstable. I know behind all this, Albania has always existed like a family. Families are very strong here. We are like a clan. It is like you are a family and your uncle is in the government but you do not go about saying things you know, because it is the honour of your family. All this lies behind the reasons things don’t change. Some generations now, are slowly changing.

But as a photographer I do the kind of photography that captures the misery of the country that one should not forget because I am often working with NGOs etc which require me to do so. I am taking pictures of people who are fighting everyday for their lives.

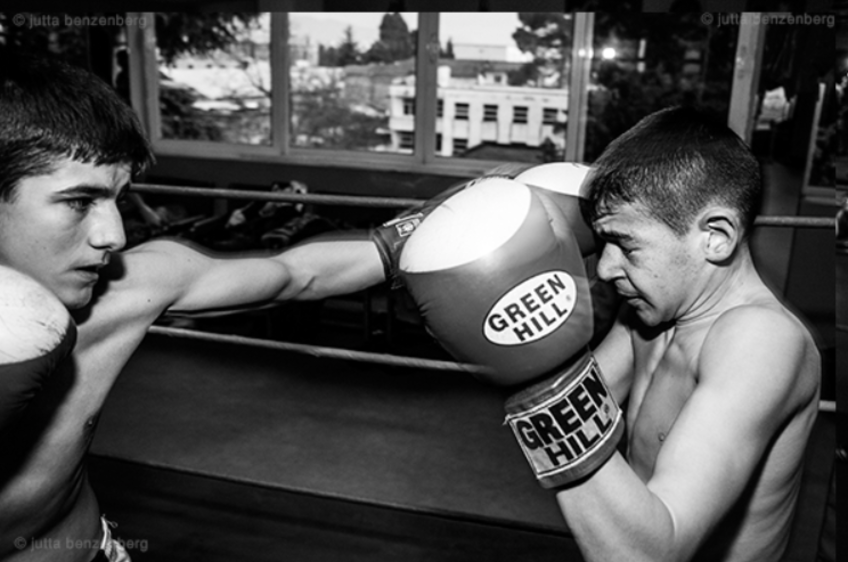

From ‘Circus in Tirana’

I was going through your work and some of the more recent work you’ve done includes lighter themes such as the ballet, the circus or the little boxers. How do you create a balance between documenting themes like this and issues of conflict?

What I wanted to do was to create some reportages. When I took pictures in 1991 I went around all of Albania and I didn’t pick a real subject where I was showing the real life of the boxers or about certain people. The photos of the opera I did because I needed something light. Something which wasn’t so dark, something for my soul and so I chose the opera as a subject to photograph.

How do you think an audience that is removed from the atmosphere of Eastern Europe is capable of understanding the work that you are doing?

No, I don’t know. People who go through my pictures don’t say “Oh I understand!” Sometimes people just go through my pictures and feel the emotions. But they don’t always have to understand. Like I said, these pictures are a part of me, I show how I feel but that doesn’t mean that the people understand them completely. I am doing photography because I am coming from a country where people do not show their emotion. We are not allowed to show our emotion, I don’t know why. So I see myself as needing to fill the missing link by putting the emotion into my pictures.

From ‘Italian Circus in Tirana’

When you’re going out to capture the kind of conflict and violence like you do, have you ever been physically or verbally attacked for doing the same?

No, never. The people here are very nice. They know I am the same as them in this country. They know I would never do something to them. When I do the pictures I don’t just simply go and shoot, I know how to respect these people. I sit with them, I talk with them, and I communicate with them through touch. I am not a stealer, I am not a tyrant. I am among them and I show them how happy I am when I get pictures that I like. When I’m working outside, the people don’t attack me also probably because I am very tall. (Laughs) Even when I do portraits the real shoot only takes about 10 minutes and then it’s over but I create an intense relation with these people like a family member, a sister. When they come in they are smiling and are shy but later, I can see their true being and that is the moment that I take the picture. And then it’s over.

From ‘Bloody Protest against PM Berisha, Tirana, Albania 2011’

What does your gear comprise when you’re out documenting protests?

Well I always have my camera in my hand and I use a fixed lens – a 35mm. I was used to a small Leica camera. The digital cameras are enormous so I prefer using a small, fixed lens. Seeing a tall me and a giant camera could just kill the moment.

How difficult was it to raise a family while documenting conflict and violence?

It wasn’t difficult at all. My family has been very supportive and proud of my work. They came to live in Albania and they love it here.

From ‘The baptism of Jehovah’s Witnesses’

Who would you say is your photographic inspiration?

Well, Josef Koudelka of Magnum. When I was in Berlin in ’87, I saw his book ‘Exiles’ and was inspired by the pictures. In fact, he came to Tirana three weeks ago and I met him and I was SO happy to meet him after so many years! He was so nice, we talked, he showed his pictures, he saw my books and now I have a picture of him and me! It was absolutely amazing. Can you imagine? He was my teacher.

You lost your archive in the fire at your home in 2007. You created a story out of the recovered negatives.

It was truly a story in itself. The day after the house burned, I went there and found all these negatives and collected them and after one year I looked at the destroyed images and some of them, especially the portraits, they began to show the reality of these people more than before. Like, there was a lady whose son was imprisoned and the destroyed negative showed her story more than before.

From ‘St. Anthony’s Day in Lac Albania 2010’

Emaho strives to promote all forms of art from the world over. What would you like to say about our endeavour?

I think Emaho as a name is chosen very well – joy, wonder, realisation. It’s great that you have photography, music, art and travel in your magazine. People from so many different backgrounds and cultures have access to it. I showed many of my friends the website and they were very excited about Emaho’s work. I wish Emaho a lot of success.

Art & Culture Interviewed by – Manik Katyal and Marukh Budhraja

Pictures by: Jutta Benzenberg