Mexico –

Many artists return to themes like love, birth, and death in their works. The best give these universals a unique and personal quality. In my experience, one of the strongest examples is Seichi Furuya, a Japanese photographer who followed his schizophrenic wife throughout her illness, all the way to her sad and premature end. Furuya’s project is perhaps the most intimate of works as the photographer provides both an objective lens and the extreme subjectivity of a husband’s eye.

For me, the best photographers are those who dare to document such grief. Think also of the series by Nobuyoshi Araki of his wife’s passing, Mitch Epstein’s iconic Family Business, Paul Fusco’s RFK Funeral Train (personal grief on a national scale) and Miyako Ishiuchi’s portrait of her mother’s clothes. Perhaps photographers are drawn to death because of both its inherent mystery and the opportunity to excise their demons. Photography as therapy.

Besides these internal aspects, the more personal a project is, the more chance it has to cut through the external clutter of our image-saturated culture. The story behind a series is now as vital as the work itself. Personal narratives about images create depth and meaning, elevating a photograph, making it truly human. The photographers and artists who go beyond shallow aestheticism are the most interesting. Technical skill can be taught and mastered: exposing your vulnerabilities in the hope of making a connection is far, far harder.

For all these reasons, it’s very exciting to stumble across a work with both a strong idea and a story. From the moment I saw Moisés by Mariela Sancari, I fell in love.

Mariela’s project, published by Spanish publisher – La Fabrica, was sparked by her father’s death, and specifically by not being allowed to see his body. She still doesn’t know why this was the case — perhaps it was due to the cause of death (a suicide) or related to her family’s religious beliefs.

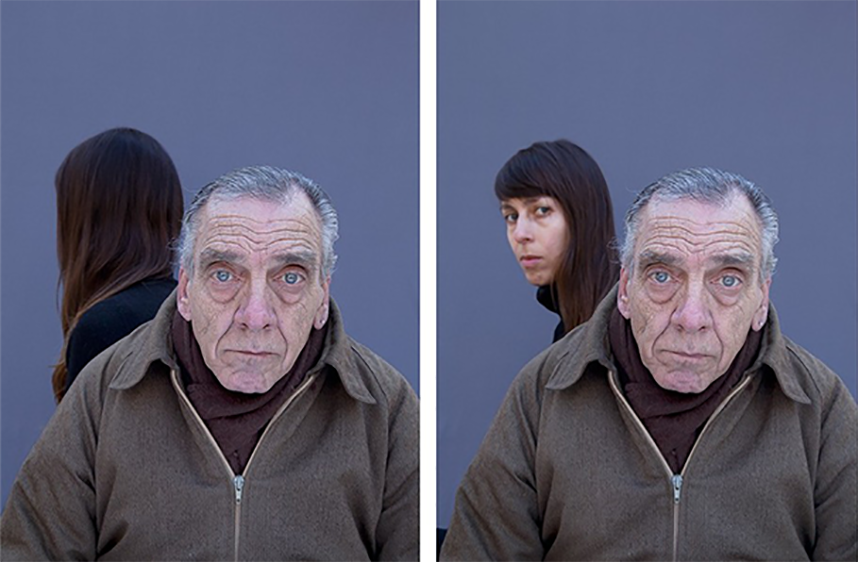

To find closure, Mariela placed a classified ad featuring an old portrait of her father. She asked men of her dad’s age to study the image and contact her should they see a resemblance.

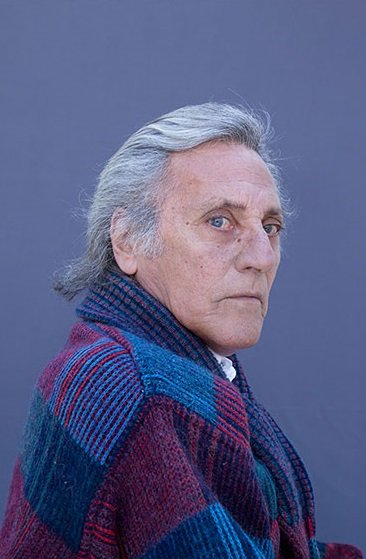

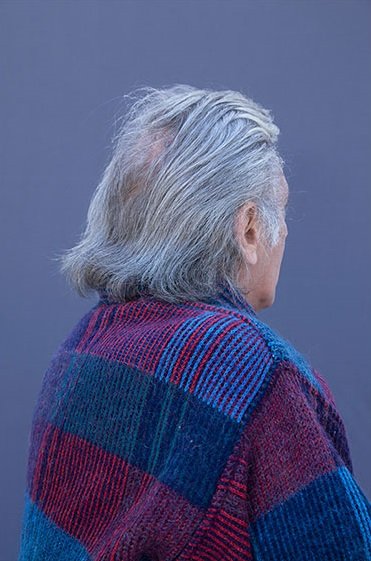

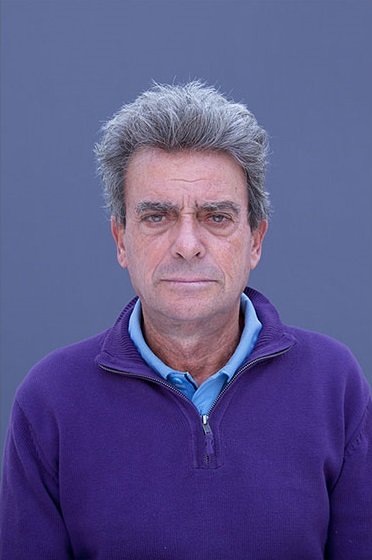

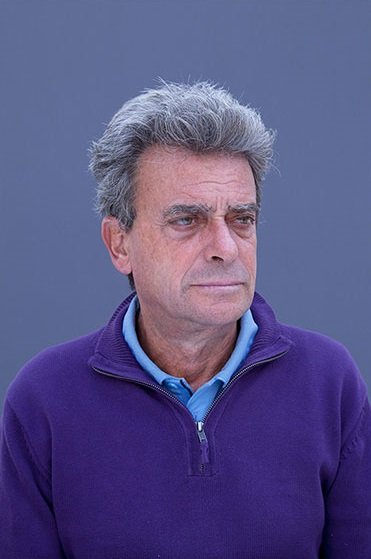

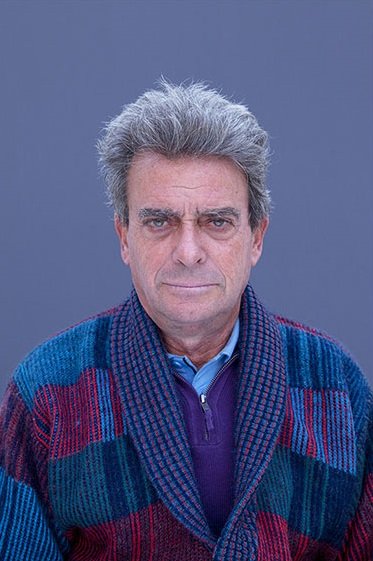

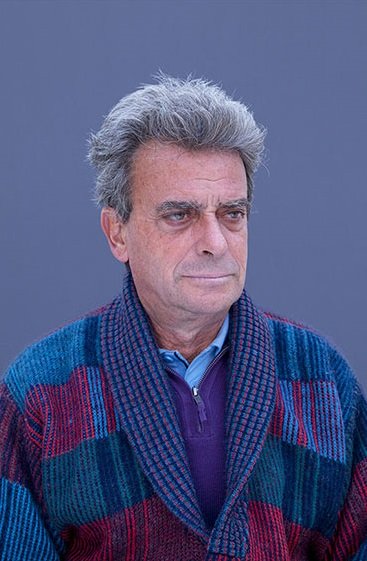

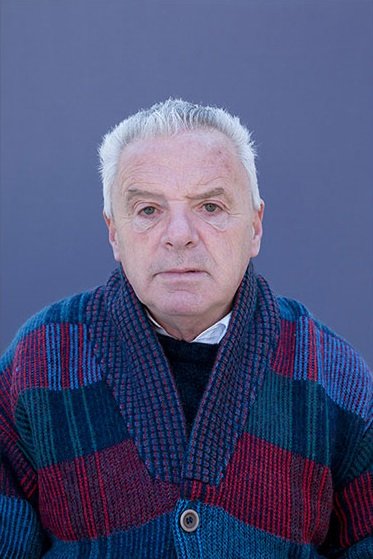

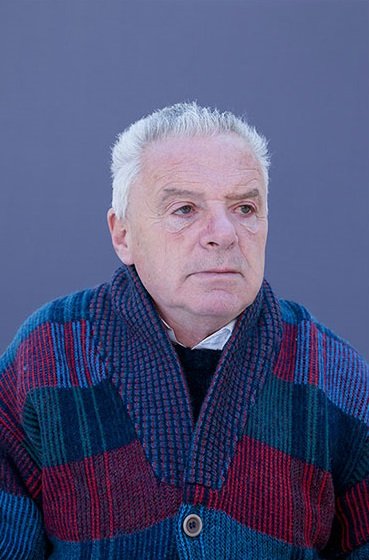

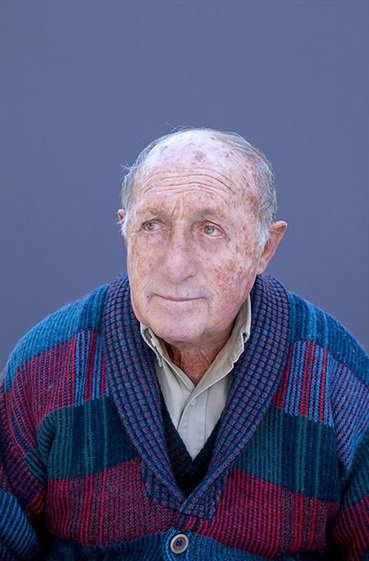

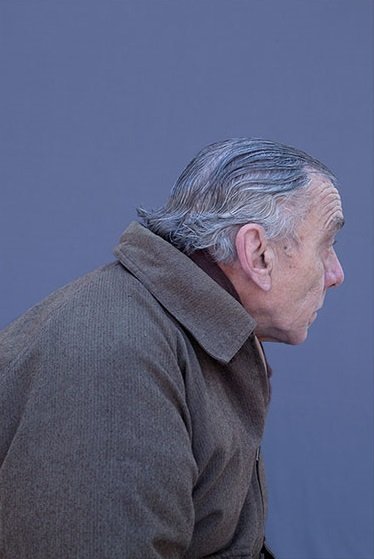

Despite the unusual nature of the request, she got the help she needed. The result is a touching series of portraits, each showing a man who embodies an aspect of Mariela’s father.

But this reconstruction goes beyond passing likenesses. Sancari asked the men to wear her father’s clothes, including one in which a stand-in dad is shown combing Mariela’s hair. While the portraits are otherwise straightforward, knowing the story behind them gives you goose bumps.

This is a moving project visualizing the journey of a young woman trying to find peace. Furthermore, it’s a demonstration of how the addition of the personal can give photography incredible power.

Photography Article by Erik Kessels

Erik Kessels is co-founder and creative director of Amsterdam communications KesselsKramer. He collects photography, published several books and exhibitions put together.