U.S.A. –

Two-time World Press Award winning photojournalist and Nikon Ambassador Ami Vitale found herself among the jury of the prestigious award this year. Ami has been working with the Executive Advisory Committee of the renowned Alexia Foundation for about six years now. Having personally documented everything from human culture, wildlife and climate change to conflict, Maoist revolutions and issues of maternal health, Ami Vitale talks about her achievements and journey as a photographer with Emaho Magazine.

Manik : How did you develop an interest in photography?

In the beginning, it was merely a passport to meeting people and learning about other cultures but now it’s much more that that. I feel a responsibility to tell stories that are often out of the headlines and to tell them with the same integrity that they have been told to me.

Manik :You were the first recipient of an Inge Morath grant for your work in Kashmir; what was that like?

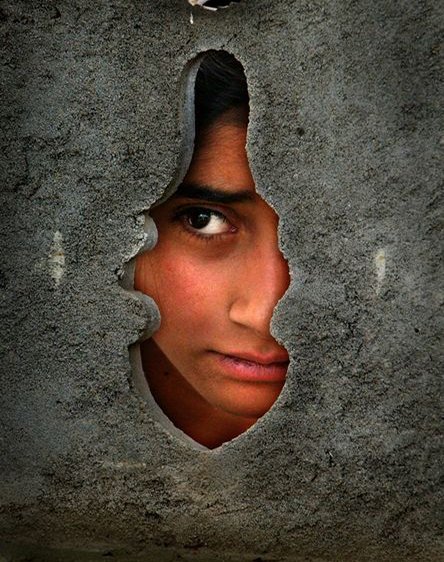

As a photojournalist, I was deeply affected by the Himalayan region of Kashmir. I wandered into the poetry of Kashmir in November of 2001 and could not let go. This place filled me with affection. It took time to understand the motivations of a people and the beauty of their land and culture. It also left scars after spending more than four years, documenting the brutality of humanity and being personally affected by the senseless deaths of close friends and innocent strangers. The work is meant to create a narrative of the people who have been shaped and changed by this conflict and hope to inspire in others the feelings that Kashmir has given me, particularly the enduring power of the human spirit.

Manik : After winning the World Press Photo award twice, what’s it like to be on the jury in 2012?

Being a judge was a fascinating experience. If I had one bit of advice for photographers who are thinking of entering, here it is. Do not enter stories which have won in previous years. It will NOT make your story more likely to win. Probably the opposite is true. The judges are looking for original content, stories that surprise or even stories of the ordinary. It does not have to be sensationalistic to win and you do not need to send images of horror and blood to get the judges attention. We witnessed a constant stream of the most sickening images of cruelty and I was grateful to see anything that showed hope.

Some of the best stories came from photographers who worked in their back yards and were able to find the joy and value in the mundane. If you can do that, you’re going to be a success.

‘A Muslim Kashmiri woman sits inside a shop with her children where traditional Islamic veils are made, March 26, 2002 in Srinagar, the summer capital of Indian held Kashmir. The shadowy group, Lashkar-e-Jabbar, also known as Allah’s Army sent a letter to a local newspaper saying that Muslim Kashmiri women must adhere to the dress code or face acid attacks beginning on April 1, 2002. The leader of the group also wrote, “if our members see any boy or girl or any illegal couple doing acts of immortality they will be killed there and then”.The same group claimed responisiblity for two acid attacks on women in Srinagar last year. Kashmir has been the center of the ongoing dispute between India and Pakistan since the region was partioned when the British left in 1947’

Manik : What has working with the Executive Advisory Committee of the Alexia Foundation been like?

I’ve been on the EAC for probably five or six years and my role has been to create awareness about their work and expand their educational reach, particularly in other countries, mainly through workshops and exhibits.

Manik : You’ve covered projects from wildlife and climate change to issues of maternal health and Maoist revolutions. What makes you choose your projects and travels?

I always look for stories which I’m not seeing in mainstream media. I’m looking for the quieter, often untold stories. Whether you’ve been in it for a year or a decade, it’s critical to commit to one story or issue or place. There are a million great photographers and the technology is there to make everybody feel like a great photographer. However, the challenge is to be consistently good and to be able to reveal more than everyone else on the subject you are working on. I think many people mistake taking pictures of exotic and beautiful places as being committed but it’s not enough just to travel and take pretty images. You have to go deep and show something original and unexpected, something that teaches and surprises and it takes time to go deep.

Manik : In India, you have covered kushti wrestling, rickshaw pullers, Kashmir, the tsunami and the Human- Elephant conflict among other topics. What has the six years spent in India taught you?

My journey as a photojournalist has taken me to places of civil unrest and also of surreal beauty. It has allowed me to witness and experience extreme poverty, destruction of life and unspeakable violence. It has also shown me that there is always joy and stories of extraordinary acts of kindness, even in the darkest places. All of these experiences have shaped who I am both as a human being and as a journalist. I would like to take what I have learned and expand my skills and knowledge so that I can share and help others give voice to their own stories and concerns. We must take advantage of the tools we have to get beyond the stereotypes and dramatic images and see past headlines to try to get a truer sense of who we all are. I see terrific opportunities to foster greater understanding, tolerance and connection between people on this planet.

Manik : What was the most dangerous part of covering the story “Tanzanians live with man-eating lions”?

Mainly, the man-eating lions.

Manik : Many photojournalists have covered the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but your idea of documenting it by including a mental institution is very unique. What made you choose to do so?

Headlines in newspapers tell us that there is a group of people who are beyond our imagination and possibility of relating to us; that they are different from us. But that is not true. When I was sent to Palestine, my editors expected to see the most dramatic examples of the conflict. On one block, there were literally dozens of photographers documenting a scene of burning cars, soldiers and violence. What began as kids throwing rocks quickly escalated into people dying. There were plenty of other stories all around us but we took these images because that what was asked of us. After several weeks, I had to ask myself were we unconsciously only telling one half the stories which were incomplete at best and even dishonest at worst? Stories of love, courage and empathy exist but I was delivering a narrative that characterised an entire region as a planet with different values.

It behoves us as journalists and storytellers to not just keep producing horror books, even though they sell, but to give a broader vision of what the world looks like. I believe that we have a greater responsibility, and obligation to also illuminate the things that unite us as human beings rather than simply emphasising our differences. This is why I chose to tell the story you mentioned. We must work harder to tell different stories with a multitude of narratives.

‘Muslim children sit inside Dariya Khan Ghhumnat Rahat refugee camp set up outside a school in the state of Gujarat in Ahmedabad, India May 10, 2002. The extent of the damage and displacement of more than 120,000 people has threatened the secular ideals of India and left the government under attack for its inadequate relief arrangements…’

Manik : What has been your most challenging project till date?

I’ve had many terrifying experiences. If I had to choose one to write about it would be my worst close call in a village in Gaza. It was after the funeral of a Palestinian who had been shot and killed. The sun was setting and I was the only journalist still there. My instincts were telling me it was time to go, but I just wanted to get one or two more frames. And then this crazy man started screaming at me, and within seconds I was surrounded by this crowd of young, very angry men. There had been a lot of killings in that area, people were very angry and I knew there was no reasoning with a mob. They wanted blood. They wanted vengeance. I had spent time earlier with the family of the Palestinian who had been killed, including several women from the man’s family.

These women, who had been standing on the periphery of the crowd, now stepped forward to escort me to safety. But if they hadn’t been there, if I hadn’t spent the day with them, I don’t know what would have happened.

‘Villagers mourn the death of five people who were killed along with 48 who were injured, when a grenade exploded in the hands of a man who was seeking to extort money from a family in Badgam district of Kashmir, March 10, 2004. Locals said the man was a former militant who was extorting money from villagers and thousands came out to mourn the deaths. Tens of thousands of people have died in Kashmir since the eruption of anti-Indian revolt in the region in 1989. Separatists put the toll at between 80,000 and 100,000.’

Manik : After experiencing the situations in Western Africa’s ‘Guinea Bissau’ what message would you like to share on ‘reality & emotions’?

If I were only to view the world through a journalists lens and see the stories that came out of Africa as reality, I would see the world very narrowly. Sadly, so much of Africa is only known for its civil wars and poverty but beyond the paved roads and beaten orange paths, there exists a beautiful culture still in touch with the nature around it. It was in this village of Dembel Jumpora, that I discovered a place that is rarely reported in mainstream press. It was not the Africa of war and famines and plagues, nor was it the idealised world of safaris and exotic animals. Instead it was a look into the simplicity and beauty of how the majority of people on this planet live. In Dembel Jumpora, every day is a struggle but there was much to be learned. I was mesmerised by the people who gave so much to open up my eyes to the beauty, wonder and sadness of their lives. Through it all, I was reminded of how similar we all are despite the distances between us.

On my last evening in the small village, I sat with a group of children beneath a sea of stars talking into the night about my return home. One of the children, Alio, innocently asked me if we had a moon in America. It seemed so symbolic and touching that he should feel like America was a separate world, and serves as a constant reminder that we are all tied together in an intricate web, whether we believe it or not.

Manik : Has controversy ever been an obstacle for your work?

Controversy always exists and it’s a part of life. Obstacles always exist in everything we do. The question is how to handle the controversies and obstacles and understand what the motivations of the people/person creating the controversy are.

Manik : How have the events witnessed in your professional career affected your personality?

It sounds romantic to travel the world but the reality is that you must be emotionally self reliant. I look back on experiences I had and now wonder how I got through them. They were sometimes unimaginable, often lonely and occasionally utterly terrifying. On the other hand, the people and experiences changed my life, showed me all the possibilities that exist and inspired me to continue. My take away from all these experiences is that we can not afford to view the world through an optic of fear and hate. As journalists, we must work harder not to tell stories through our own paradigm of values. Unless we have empathy for those who have a different viewpoint than our own, than we justify the existing divisions in our world.

Manik : What do you think can be done to promote photography among Kashmiri communities that lack proper guidance, platforms for exposure or even something as basic as the Internet?

They must first help one another. By unifying and passing along the knowledge, they will all benefit greatly. Secondly, rather than trying to emulate the same things they see as being successful, they need to find their own voices and vision. I see the same stories out of Kashmir and there are plenty of other stories. Some photographers have been fantastic and looking for new ways to portray the region but for

the most part, it’s a similar vision. So the biggest issue in my opinion is to start looking at life with a new lens. Lastly, I think platforms such as the one you want to create will give them greater exposure. They can also do more to grab the opportunities that are out there for all photographers. I would look at examples like Shahidul Alam and Drik and the elder journalists could create a model much like his school and agency.

‘Kashmir exhibit’

Manik : Do you think video will make storytelling through still photography obsolete?

The medium we work in is changing and video is now playing a much bigger role in what we do. Cameras like the one I carry can shoot HD video and it can enhance our abilities as storytellers. This is already playing a big role in my future. In a time when media is struggling and searching for a new path, I’m

finding that I am busier than ever telling meaningful stories in new ways for a variety of outlets. I went back to school to study film and believe it’s an exciting time to be a photographer. Having the tools

and this skill can create more opportunity for all of us. The old models of business are in crisis, but opportunities lie ahead. We must redefine ourselves as technologies create more opportunities.

‘‘MIRHAMA, KASHMIR – SEPT. 21: Relatives of Naz Banu, who was killed during an attack on leading politician Sakina Yatoo, mourn over her body during her funeral in the northern Kashmir town of Mirhama, Saturday, Sept. 21, 2002. At least 11 people were killed and a second abortive bid was made to assassinate a leading woman politician Saturday, just days before a crucial second round of polls in the strife-torn northern Indian state of Jammu-Kashmir. (Photo by Ami Vitale/Getty Images)’ ‘

Manik : What are the key elements that Ripple Effect Images is working on?

For quite some time, my work has focused on environmental issues. The funny part is, very little of what I photograph is nature or landscape. Stories about the land are always stories about people. You cannot talk about one without the other. If recent storms and natural disasters tell us anything, it is that we are inextricably linked to the forces of nature. Climate change does impact us; no one is immune to it. Two

years ago, I made a film about climate change in Bangladesh. I’ve seen firsthand, how women in developing countries bear the greatest burden as a result of these climatic shifts. For example, they must walk farther for water (some women walk up to 11 hours a day for poor quality water) or they must stay behind and care for their children when floods force the men to move and seek better resources.

I am thrilled to be working with the amazing group of people that make up Ripple Effects Images. Ripple Effects is a group of journalists dedicated to the mission of raising awareness and funding to help empower women and girls in emerging nations around the world. The organization works with NGOs, ambassadors, corporate leaders, and the State Department to document and support projects that help women help their families, communities, and the planet. Ripple Effects recognises that programs that give women the tools to affect change are some of the most effective programs, because women reinvest those resources and share them with others.

Photography Interviewed by: Manik Katyal and Sujanya Das

Pictures by: Ami Vitale