Emaho: Could you share what first drew you to photography and images during your early days? Was there a particular moment or experience that sparked your fascination?

EK: When I was eleven years old, my sister died in an accident. Very soon after, my parents began searching for her “last image.” Eventually they found an unremarkable snapshot, far from perfect, but enlarged and framed it as the final photo ever taken of her. I remember vividly how, in that moment, the meaning of a photograph changed for me: something ordinary suddenly carried enormous emotional weight.

Later, as an art director and graphic designer, I spent many years working with photographers. A key moment came in 1996, when I worked in London with Simon Larbalestier, known for his iconic Pixies album covers. That collaboration opened my eyes to photography’s expressive power, and since then I’ve worked with many non-commercial, more experimental photographers.

Emaho: How did your background in advertising influence your evolving relationship with photography and art?

EK: As an art director, I constantly select, edit, and shape images created by others. In a way, this made me far more comfortable working with other people’s photographs than with my own.

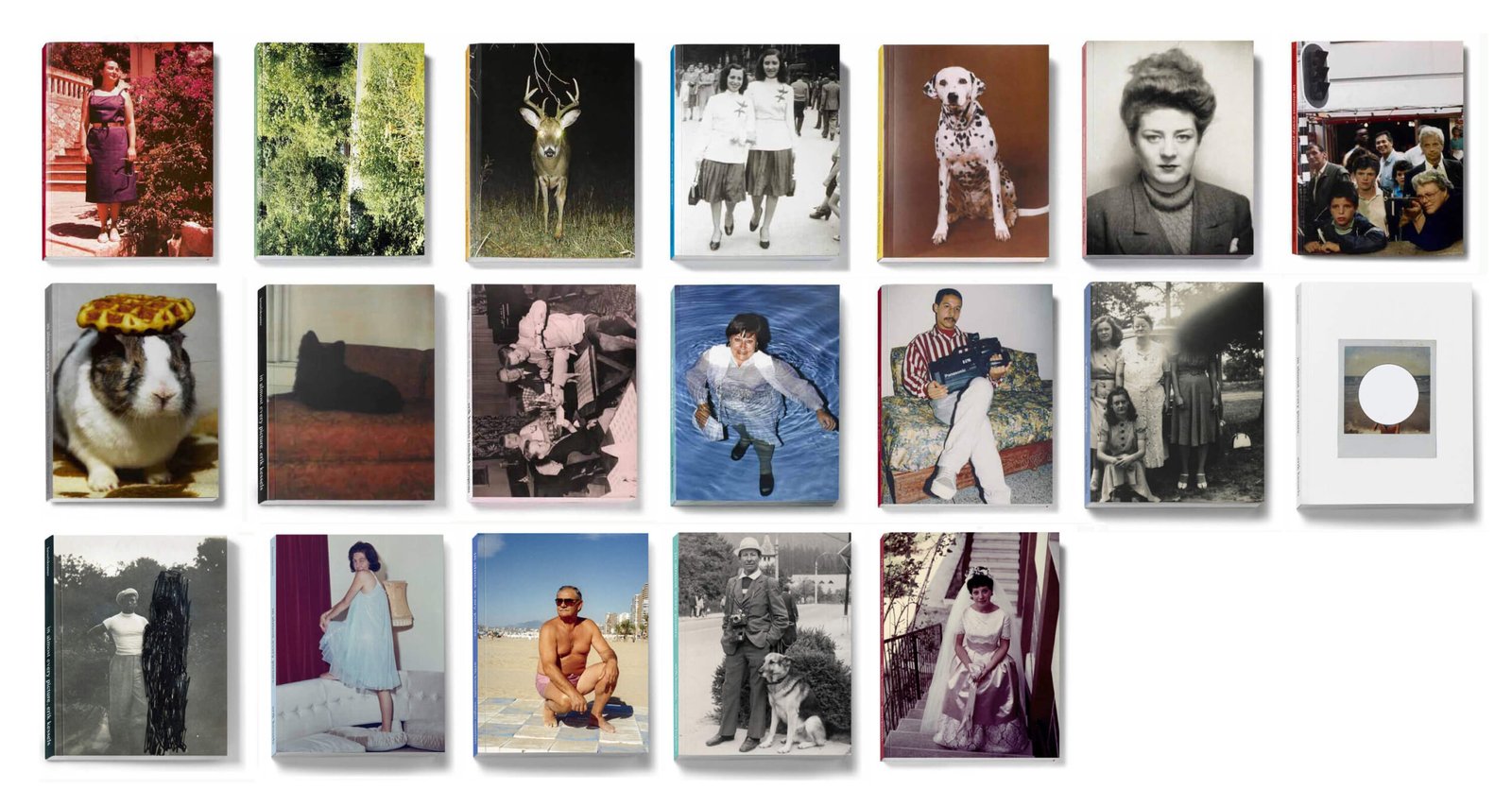

My interest in “found photographs” began when I started discovering private snapshots and personal belongings at flea markets. It fascinated me that such intimate objects could end up in public spaces. Re-appropriating these images, removing them from their original context and giving them a new life, felt entirely natural to me.

This process mirrors advertising in an odd way: both involve recontextualizing images, but in art I can do it with a much greater sense of freedom.

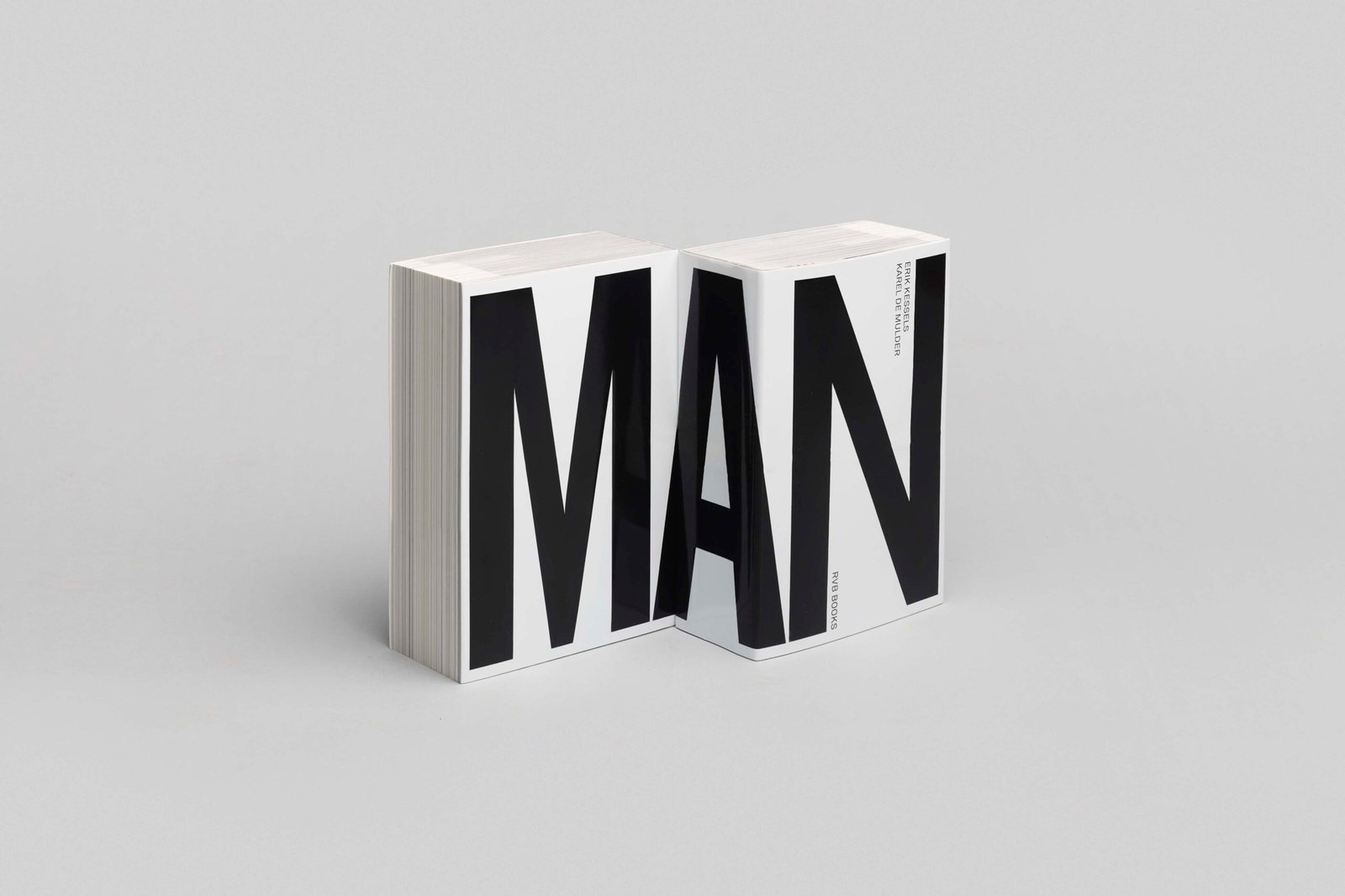

Emaho: You have a profound passion for photobooks. What is it about this form that captivates you more than other photographic mediums?

EK: Every medium has its own logic, challenges, and possibilities. A photobook is ideal for storytelling, it offers a linear, intimate, narrative structure that unfolds page by page. You can set a rhythm, create suspense, or let the viewer breathe.

But a book also has limitations, and that’s part of its beauty. Exhibitions or installations allow for sound, movement, participation, even smell. A book, on the other hand, is a quiet, self-contained universe.

What captivates me is that a photobook becomes an object someone can return to, hold, and experience in private.

Emaho: Your creative process often involves ‘found’ images. How do you approach selecting and curating these images into new meaningful narratives?

EK: Selecting and curating found images is the most exciting,and most crucial, stage of the process. I look for connections, echoes, contradictions, and unexpected stories hidden inside unrelated snapshots.

Working with images I didn’t create makes it easier to stay open, playful, and experimental. I don’t carry the emotional attachment of the “original author.” Instead, I can approach the images with curiosity, humour, or even tenderness, allowing new narratives to surface from what once seemed random.

Emaho: The art of failing is a concept you’ve explored extensively. How do you define ‘failure’ in photography, and what lessons does it offer?

EK: Many creatives stay in their metaphorical “Frontyard”, the polished portfolio, the perfected website, the carefully curated Instagram feed. It’s the space where everything is finished and presentable.

But perfection is a terrible place to start new work. For that, you need to go into your “Backyard”, the hidden, messy, experimental space where you can fail freely. That is where genuine ideas begin.

Failure is not a mistake; it’s a condition for invention. When something doesn’t work, it often reveals something truer and more personal.

Emaho: How do accidental or ‘failed’ photographs reveal deeper aspects of human behaviour and pictorial culture?

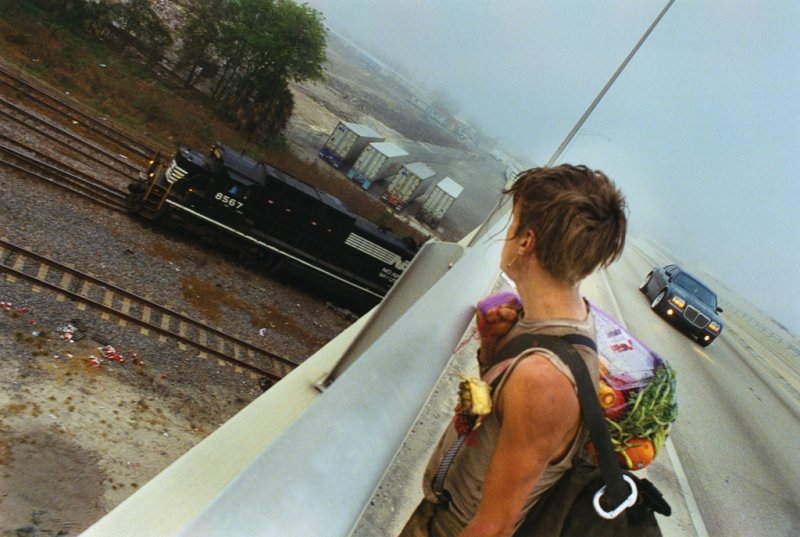

EK: Failed photographs expose everything we normally try to hide: hesitation, clumsiness, surprise, misunderstanding. They reveal the human presence behind the lens and the subject.

Perfect images tend to flatten emotions. But imperfections – blur, misalignment, accidental gestures – tell a richer story about how humans behave, intervene, and influence the image. They remind us that photography is not just a technical craft but a deeply human activity.

Emaho: You once said, “All the great photographs have already been taken.” What does this mean for creativity today?

EK: We’re at a tipping point in visual culture. So many photographs repeat earlier ones, consciously or not. Everything seems categorized: landscape, portrait, street photography, documentary.

With the rise of AI, this becomes even more pronounced. Images are now generated from vast datasets of existing photographs. The result is often what I call “statistical hallucinations”, pictures that resemble countless others.

So in that sense, yes, the great photographs might already exist. But that is not the end of creativity; it’s simply a shift in its focus.

Emaho: Does this mean photography is ‘dead,’ or does it challenge us to rethink what photography can be?

EK: Photography is definitely not dead. Quite the opposite: the overwhelming abundance of images forces artists to think differently.

The confusion and saturation can inspire new approaches, playing with archives, mixing mediums, questioning truth, or exploring the boundaries between photography, performance, and technology.

Photography is not ending; it is mutating.

Emaho: How do you see ‘pictorial behaviour’ evolving in today’s social-media-saturated world?

EK: We have become incredibly aware of the camera. In analogue times, people behaved awkwardly or shyly in front of it. Today even children know how to pose, perform, and manipulate their own image.

The life cycle of a photograph has changed dramatically. We used to keep photographs for decades; now we “use” them for hours or days. They have become temporary gestures rather than lasting memories.

Emaho: What role do irony and humour play in your work, and why do these elements resonate so strongly?

EK: Any powerful artwork must evoke a strong emotion: confusion, beauty, discomfort, irony, humour, something unmistakably felt.

For me, humour and irony emerge naturally. They are instinctive tools for revealing truths that might otherwise be too heavy or too sentimental.

And I believe art should be polarizing. You should either love a work or hate it. The middle ground is the real enemy.

Emaho: Your exhibitions combine archives, personal collections, and public contributions. How do you maintain respect for original images while transforming them?

EK: I approach exhibitions as installations, experiences rather than displays. I remove images from their original context and place them in entirely new situations. This shift allows people to look at mundane or forgotten photographs with fresh attention.

I always respect the content and the human story behind an image. What I transform is the context, not the integrity of the subject.

Emaho: Can you share a memorable discovery that shaped one of your projects?

EK: Meeting Ria van Dijk changed a great deal for me. She was a Dutch woman who, from her teenage years, had her portrait taken annually at a fairground shooting gallery. Whenever she hit the target, the bullet triggered the camera’s shutter.

She continued this ritual until she was 101 years old. When I met her at 94, we immediately connected; she had a sharp humour and a wonderful presence.

After publishing in almost every picture #7, she became something of a local legend, and her photographs are now in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. It remains one of the most moving collaborations.

Emaho: With photo festivals growing worldwide, what is their importance in sustaining photographic culture?

EK: The primary purpose of a photo festival should be to stretch the boundaries of photography, not to comfort visitors with what they already know.

Too many festivals act like visual supermarkets, offering exactly what people expect. But a good festival should leave you slightly disoriented, questioning your own assumptions.

Photography can be too pleasing; festivals should challenge that.

Emaho: How will photobooks evolve as creative objects in the digital age?

EK: Printed art and photography books are flourishing. Increasingly they become not just books but objects, portable exhibitions, tactile documents that allow ideas to travel.

Paper choice, sequencing, design, and printing methods all become part of the artistic language. There are endless ways to express yourself within the format, and I believe the photobook will remain one of the most inventive spaces for photographers.

Emaho: Looking ahead, what emerging trends or forms in photography excite you most, and how do you plan to engage with them?

EK: I believe the question “why” will soon matter far more than “how.” Technically, we can produce almost any image imaginable. But the conceptual reason behind an image will become crucial.

I hope artistic photography continues to embrace experimentation, questions, mistakes, and emotional expression, rather than becoming merely decorative. That is where its future lies.